CHAPTER 6 Localization and Spread of Disease

Imaging to investigate problems of the abdomen and pelvis is often focused to a specific organ or body system. This can be problematic because diseases are often not confined to a specific organ, and pathologic processes can present distant from their origins. A thorough approach to abdominal and pelvic disease processes necessitates a basic understanding of how disease is contained and spread within the abdomen and pelvis. Such knowledge allows one to diagnose disease distant from its site of origin and predict the primary site of abnormality. This chapter considers how diseases are spread throughout the abdomen and pelvis, and examines relevant anatomic relations, the classic concepts of intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal, and the unifying concept of the subperitoneal space.

PERITONEUM

The peritoneum is defined by a continuous serous membrane that divides the coelomic cavity into the peritoneal cavity and the subperitoneal space (Fig. 6-1). The peritoneal lining develops from a splitting of the lateral mesoderm. The somatic mesoderm (parietal peritoneum) lines the body wall, and the splanchnic mesoderm (visceral peritoneum) covers the abdominal viscera and forms the abdominal mesenteries. The peritoneal cavity is a potential space that is outside the peritoneal lining and contains the suspended abdominal viscera. The space beneath the parietal peritoneum, containing a variable amount of areolar tissue, is the extraperitoneum. Early in embryonic life, the extraperitoneal space extends into the mesenteries and forms the subperitoneal space. The mesenteries provide avenues for the blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves of the abdominal viscera to course to and from the extraperitoneum. The single subperitoneal space lies beneath the peritoneal lining and contains both the extraperitoneal space and the network of interconnecting mesenteries of the abdomen and pelvis.

MESENTERIES AND LIGAMENTS OF THE ABDOMEN AND PELVIS

Ventral and Dorsal Mesenteries

The primitive mesentery is divided by the primitive gut into the ventral and dorsal mesenteries. The ventral mesentery regresses except for the portion that is associated with the foregut (ventral mesogastrium). The rapid growth of the liver within the ventral mesentery divides this mesentery into the lesser omentum (gastrohepatic ligament) and falciform ligament. The visceral peritoneum forms the liver capsule as it encases the liver, except for the surface embedded within the septum transversum (the bare area). Here, the peritoneum is reflected as the coronary ligament. The reflections of the coronary ligament again oppose each other as they attach to the parietal peritoneum anteriorly as the falciform ligament and laterally as the triangular ligaments. The falciform ligament extends from fissure for the ligamentum venosum to the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 6-2). The falciform ligament provides a potential conduit for transmission of inflammation or hemorrhage from remote organs such as the pancreas (via the gastrohepatic ligament) to the anterior abdominal wall.

The dorsal mesentery extends in continuity from the intraabdominal portion of the esophagus to the rectum. This mesentery, in addition to giving support to the gut, serves as a conduit for the blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves of the body organs. The spleen and dorsal portion of the pancreas appear by the fifth gestational week between the folds of the dorsal mesogastrium, which contains the splenic artery and vein, accompanying nerves, and lymphatics. The mesentery of the pancreas fuses with the posterior parietal peritoneum, leaving the spleen suspended by the splenorenal ligament and gastrosplenic ligament (Fig. 6-3). This is followed by posterior fusion of the splenorenal ligament. Inflammation or neoplasm may extend between the stomach and spleen via the gastrosplenic ligament. It is important to recognize that the pancreas is positioned beneath the posterior parietal peritoneum. The pancreas is centrally located within the subperitoneal space and in continuity with the abdominal organs via their mesenteric attachments. Neoplasms and inflammation can spread from the pancreas directly to the spleen via the splenorenal ligament, to the colon via the transverse mesocolon, to the liver via the hepatoduodenal ligament, and into the small bowel mesentery along the superior mesenteric vessels (Fig. 6-4). It is important to remember that the derivatives of the dorsal and ventral mesenteries remain in continuity after development, and that the individual named mesenteries are identified by their contained vessels (Tables 6-1 and 6-2).

Table 6-1 Ventral Mesentery Derivatives

| Name | Landmarks |

|---|---|

| Gastrohepatic ligament | Left gastric vessels, right gastric vessels |

| Hepatoduodenal ligament | Portal vein, hepatic artery, bile duct |

| Falciform ligament | Ligamentum teres |

Table 6-2 Dorsal Mesentery Derivatives

| Name | Landmarks |

|---|---|

| Gastrosplenic ligament | Short gastric vessels, left gastroepiploic vessels |

| Splenorenal ligament | Splenic artery and vein |

| Gastrocolic ligament | Right and left gastroepiploic vessels, gastrocolic trunk |

| Transverse mesocolon | Middle colic vessels |

| Greater omentum | Epiploic vessels |

Gastrohepatic and Hepatoduodenal Ligaments

The ventral mesogastrium is one mesentery in continuity as it attaches the foregut to the ventral abdominal wall. Its derivatives include the lesser omentum and the falciform ligament. The lesser omentum (gastrohepatic ligament) extends from the liver to the stomach. More specifically, this ligament extends from the fissure for the ligamentum venosum and porta hepatis to the lesser curvature of the stomach (Fig. 6-5). The gastrohepatic ligament contains the left and right gastric arteries, coronary vein, and left gastric lymph nodes. The gastrohepatic ligament provides a pathway for bidirectional spread of disease between the stomach and the left hepatic lobe (Fig. 6-6). The free margin of the lesser omentum (hepatoduodenal ligament) attaches to the duodenum ventrally and contains the portal vein, hepatic artery, and common bile duct.

Ligamentous Support of the Colon and Small Bowel

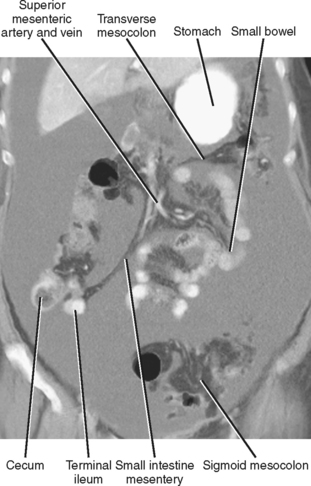

The transverse mesocolon is derived from the dorsal mesocolon and is in continuity with the root of the small-bowel mesentery (Fig. 6-7). The phrenicocolic ligament is the left lateral extension of the root of the transverse mesocolon, and the duodenocolic ligament is the right lateral extension. The posterior reflections of the small intestine mesentery extend from the region below the transverse mesocolon in the left upper abdomen to the right lower abdomen, providing continuity between the left upper and right lower abdomen (Fig. 6-8). The dorsal mesocolon undergoes extensive posterior fusion after reentry to the abdominal cavity during development. The ascending and descending portions of the dorsal mesocolon lie in their lateral positions and fuse with the parietal peritoneum, as does the mesorectum. For imaging purposes, the ascending and descending colon and rectum are considered extraperitoneal structures. The appendix cecum, transverse mesocolon, and sigmoid mesocolon persist (Fig. 6-9). Therefore, the transverse and sigmoid portions of the colon are considered to be intraperitoneal. However, it is important to realize that the entire mesentery of the colon and rectum remains in continuity regardless of fused portions.

Pelvic Ligaments

Of the numerous supporting ligaments of the pelvis, the broad ligament is the most relevant for disease spread and containment. The broad ligament forms from a mesenchymal shelf within the pelvis and bridges the lateral pelvic walls (Table 6-3). The visceral peritoneum encases the broad ligament, uterus, and adnexa. Specialized portions of the broad ligament form the mesovarium and mesosalpinx superiorly, and the cardinal ligament inferiorly. The broad ligament contains the blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves of the uterus and adnexa. Thus, the subperitoneal space extends into the pelvis as the broad ligament (analogous to the mesenteries of the abdomen) and interconnects the female pelvic organs with the abdomen.

| Name | Landmarks |

|---|---|

| Broad ligaments | Uterine vessels, fallopian tubes, ovaries, uterus |

| Round ligaments | Inguinal canals |

EXTRAPERITONEAL SPACES

Spread and containment of extraperitoneal disease is related to the anatomy of the extraperitoneal spaces. The localization of a process within an extraperitoneal compartment also allows for development of a differential diagnosis related to organs within that space. The three classic extraperitoneal spaces are demarcated by fascial planes that divide the extraperitoneum into compartments with specific contents and relations. The anterior and posterior renal fascias (collectively known as Gerota’s fascia, although the posterior renal fascia was first described by Zuckerkandl) segment the extraperitoneum into the anterior pararenal, posterior pararenal, and perirenal spaces (Fig. 6-10). The anterior and posterior pararenal spaces combine below the iliac crest and continue inferiorly as the extraperitoneal space of the pelvis, providing anatomic continuity.

Anterior Pararenal Space

The anterior pararenal space lies between the posterior parietal peritoneum and the anterior renal fascia (Figs. 6-11 and 6-12). This space contains the pancreas, extraperitoneal portion of the duodenum, and the ascending and descending colon. Its cephalad extent is the bare area of the liver (on the right) and its caudad extent is the level of the iliac fossae. The anterior pararenal space is continuous as the subperitoneal space of the mesenteries of the upper abdomen, transverse mesocolon, and small bowel. In this manner, disease processes may spread bidirectionally between the organs of the upper abdomen, pancreas, small bowel, and colon. The anterior pararenal space is constrained laterally by the lateroconal fascia formed by fusion of the layers of the anterior and posterior renal fascia. Anatomically, the anterior pararenal space is compartmentalized into colonic and pancreaticoduodenal compartments by fusion of the primitive mesenteries. This process of fusion results in creation of the retropancreaticoduodenal and retromesenteric interfascial planes that can serve as conduits for spread of fluid within the extraperitoneum.

Figure 6-11 Axial enhanced computed tomographic scan in a patient with acute pancreatitis and anterior pararenal fluid.

Perirenal Space

The perirenal space lies between the anterior and posterior renal fascia. Pathologic processes or fluid collections occurring within the right or left perirenal space most often do not cross the midline, as the renal fascias fuse with the connective tissue surrounding the aorta and inferior vena cava. The caudad extent of the perirenal space is at the iliac crest where the fascial layers are poorly fused and blend with the periureteric connective tissue. Controversy exists as to the anatomic patency of the inferior perirenal space. In practice, however, perirenal fluid collections are usually confined to the perirenal space (Fig. 6-13). If there is deficiency in the cephalad extent of the anterior renal fascia, the superior perirenal space may be open. In such a case, abnormalities of the perirenal space can extend cephalad with the anterior pararenal space to the level of the bare area of the liver.

Bare Area of the Liver

The bare area of the liver is formed by the peritoneal reflection over the posterior portion of the liver embedded in the diaphragm. The bare area is delineated by the falciform ligament (anterior), the coronary ligament (central), and the right and left triangular ligaments (lateral). It is the cephalad extent of the right anterior pararenal space. Occasionally, the perirenal space is open superiorly and in continuity with the anterior pararenal space in the region of the bare area of the liver. Right pararenal or perirenal hematoma, infection, or neoplasm may extend superiorly to the bare area of the liver, and hematoma from hepatic injury may enter the pararenal or perirenal space via the same pathway. Abscesses can also arise from the liver and extend into the bare area. The bare area of the liver is difficult to visualize on cross-sectional imaging modalities in the absence of peritoneal fluid. However, in patients with sufficient ascites, the bare area is identified as the area along the posterior surface of the liver adjacent to the diaphragm that is spared by the fluid (see Fig. 6-5).