13 Pediatric interventional ultrasound

Pediatric interventional radiology is a rapidly growing subspecialty, and many procedures formerly the responsibility of pediatricians and pediatric surgeons are now performed by radiologists.1,2 Ultrasound guidance is ideal for interventional radiology in children (Box 13.1). It is the only imaging required for some procedures and is the starting point for many others (Box 13.2).

BOX 13.2 Ultrasound-guided interventional techniques

ANESTHESIA

There are widely differing ideas about the appropriate form of anesthesia for pediatric interventional radiology. Some centers use mainly intravenous sedation (using various drugs), with good results.2 At our institution, we prefer general anesthesia (GA) on the grounds that it is less unpleasant for the child and may make the procedure safer.

VENOUS ACCESS

Central venous access procedures form a large part of the workload in pediatric interventional radiology, comprising nearly 50% of the cases in our practice.1 The ability to provide routine venous access both for the administration of medication and for diagnostic blood sampling has become a basic requirement in the acute medical care of the child. The major indications for central venous access in children include total parenteral nutrition, prolonged intravenous therapy, use of toxic chemotherapies, difficult access, frequent blood transfusions or sampling and hemodialysis.

The following types of device are used:

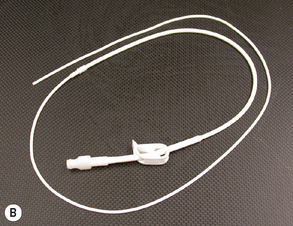

• PICC: peripherally inserted central venous catheters are often used for toxic therapies, long-term antibiotics and total parenteral nutrition. They are unsuitable if high infusion rates are necessary.

• Tunneled catheters (e.g. Hickman or Broviac catheters) pass through a subcutaneous tunnel before entering a central vein. They can have more than one lumen, and are intended for long-term use.

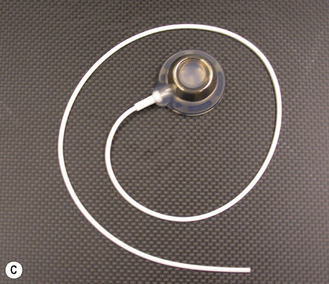

• Ports (e.g. Port-a-Cath) are subcutaneously implanted reservoirs attached to central venous catheters. They are intended for long-term intermittent use.

The selection of catheter to be inserted depends on several factors:

• type of infusion and frequency with which it will be infused

• venous anatomy and access sites

• previous intervention at the intended site for access and future needs for access

• clinical history and coagulation status

• preference of the physician or patient

The use of ultrasound guidance makes central venous access easy, quick and safe in all but the most difficult cases. Potential advantages over surgical placement of central lines include a very high success rate at the first site attempted, a good cosmetic result because of the short puncture site incision, a short procedure time and no need for preoperative imaging in children who have had multiple central veins accessed in the past.1 Table 13.1 lists, for various veins, indications for access.

Table 13.1 Ultrasound-guided venous access

| Access | Common indications | Other indications |

|---|---|---|

| Internal jugular veins | Central venous catheterization | |

| Subclavian veins | Central venous catheterization | Pacemaker insertion |

| Femoral veins | Central venous catheterization | |

| Upper limb veins | PICC insertion | Other venous intervention |

| Hepatic veins | Cardiac intervention | Central venous catheterization |

| Portal venous system | Pancreatic venous sampling |

IVC, inferior vena cava; PICC, peripherally inserted central venous catheter; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

Technique

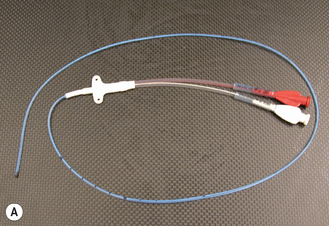

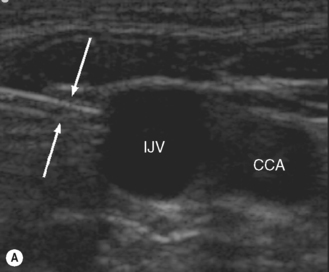

A high-frequency linear array probe is used for most procedures. The puncture can be performed with the needle either parallel to or perpendicular to the long axis of the probe. A 21-gauge needle (which accepts a 0.018-inch guidewire) is usually used in small children. In older children it is possible to use 19- and 18-gauge needles (which accept 0.035- and 0.038-inch guidewires, respectively). Non-tunneled catheters can be inserted over the guidewire following dilation of the tract with a vascular dilator. The insertion of tunneled catheters requires the use of a peel-away sheath (Fig. 13.1).

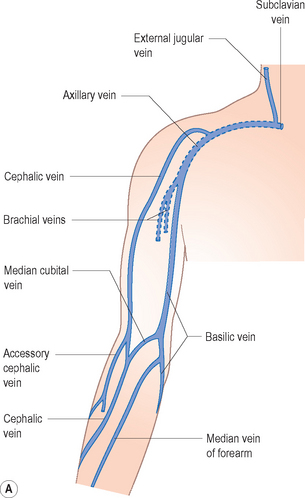

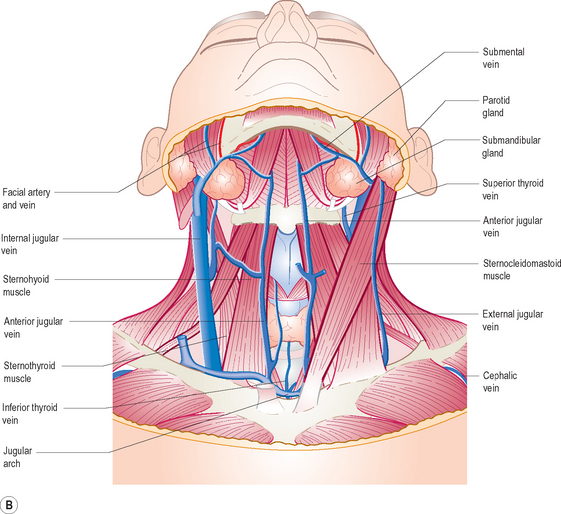

Venous access sites

The most frequently used central veins are the internal jugulars, subclavians and femorals. The right internal jugular vein (Fig. 13.2) is usually the preferred site for insertion of temporary and tunneled central venous catheters and venous port devices. When this vein cannot be used, the left internal jugular vein is preferred to the subclavian veins. This advice is not evidence-based but relies on the assumption that the risks of pneumothorax and inadvertent arterial puncture are less with ultrasound-guided jugular puncture.

The subclavian veins can be punctured, with ultrasound guidance, from either a supraclavicular or infraclavicular approach. In patients with chronic renal failure the subclavian veins are not used, because the large catheters used for hemodialysis often cause subclavian vein stenosis, which may prevent the use of the ipsilateral upper limb for creation of a dialysis fistula (Fig. 13.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree