26 Congenital/Developmental Spine Abnormalities

26.1 Congenital and Developmental Spinal Abnormalities

The evaluation of nontraumatic structural abnormalities is probably the aspect in which imaging of the pediatric spine differs the most from that of adults. The evaluation and study of trauma, neoplasms, and infectious/inflammatory processes of the pediatric spine have many more similarities to those of adult imaging. Ultimately, understanding many of these pediatric conditions requires familiarity with embryology. However, because familiarity does not mean mastery, it should not be a cause of fear in addressing congenital disorders of the pediatric spine.

26.2 Anomalies of Segmentation and Clefts of the Vertebral Bodies

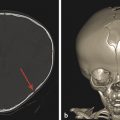

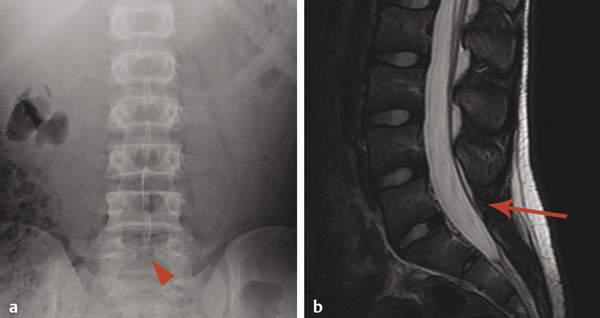

Because the vertebral column develops from the same neural tube that segments to give rise to the vertebrae, the failure of two vertebrae to separate, leaving them instead in continuity, is referred to as incomplete segmentation. This is in contradistinction to the term “fused,” which is more properly applied to an acquired fusion of two vertebrae that had already segmented in the normal manner. During segmentation, additional variants can occur in vertebral morphology, including persistent sagittal clefts between vertebrae (“butterfly vertebrae”) (Fig. 26.1), hemivertebrae, and mutlilevel incomplete segmentation blocks. The more complex anomalies of vertebral segmentation are often associated with congenital scoliosis. Although sagittal clefts are the most common anomalies of vertebral development, some skeletal dysplasias (e.g., Kniest dysplasia) can be associated with coronal clefts (Fig. 26.2).

Anomalies of vertebral segmentation can create a challenge in numbering the vertebrae for the purposes of reporting findings in their imaging. If any atypical features of vertebral segmentation exist, the system used for vertebral numbering must be described in the report. When there are atypical features, every possible attempt should be made to determine a numbering system that allows for the appropriate number of vertebrae. Theoretical vertebrae, such as T13 and L6, do not exist, particularly because there is no T13 or L6 nerve root, dermatome, or sclerotome. Nearly all cases of anomaly in vertebral segmentation can be analyzed to determine a numbering system that accounts for the appropriate number of nerve roots and dermatomes.

26.3 Clefts of the Posterior Neural Arch

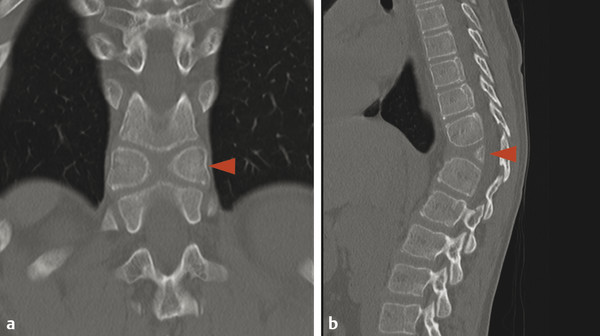

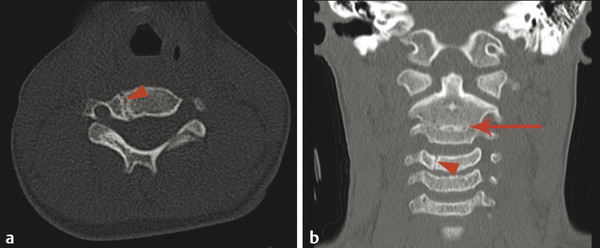

There are several characteristic locations for osseous clefts within or at the junction of the ossification centers of the posterior neural arch (Fig. 26.3). Additional osseous abnormalities can occur within a given vertebral level in the joining of the different ossification centers of the vertebra and posterior neural arch at that level. Perhaps the most commonly encountered osseous cleft is midline incomplete closure of the posterior neural arch without the protrusion of meninges or neural elements (Fig. 26.4). Classically this has been described as “spina bifida occulta,” but this term raises concern on behalf of patients, referring physicians, and (potentially) insurance companies, and a midline incomplete closure of the posterior neural arch without the protrusion of meninges or neural elements can instead be described with the statement that “incidental note is made of focal congenital nonunion of the posterior neural arch of (vertebral level),” if this condition is to be described at all. Such incomplete closure is most commonly encountered at C1 and S1, and personally I tend to mention it in the body of a report for C1, particularly for studies performed for cervical spinal trauma, and rarely mention it when it is present in S1 because it rarely has pathologic significance at that level of the spine. Referring in a report to incomplete closure of the posterior neural arch as spina bifida occulta introduces unneeded anxiety; the clefts resulting from such incomplete closure have no clinically relevant relationship to spina bifida, which is generally used to describe an open spinal dysraphism, such as a myelomeningocele.

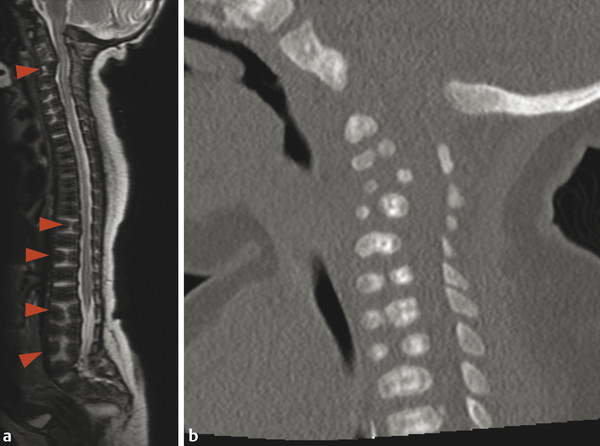

Following midline incomplete closure of the posterior neural arch of C1 and S1, the next most common vertebral cleft is a cleft of the pars interarticularis, also referred to as spondylolysis. This cleft, which may not be a congenital cleft, occurs in the posterior elements of the vertebra approximately between the level of the superior and inferior articulating facets, and is most common at L5. At L5 it can be unilateral or bilateral. When a cleft of the pars interarticularis is unilateral, there is sclerosis and thickening of the contralateral pedicle, probably as the result of increased stress on it. When such a cleft is bilateral, the patient may have an anterolisthesis (also known as a spondylolisthesis). It is therefore possible to have spondylolysis with or without spondylolisthesis. Although a cleft of the pars interarticularis can be congenital, most such clefts are probably chronic stress fractures. In the pediatric and adolescent populations, those at greatest risk for such fractures are athletes with excess stress at the lumbosacral junction, including gymnasts and cheerleaders, as well as punters in football. These fractures can be identified on radiography and computed tomography (CT). Magnetic resonance imaging may show adjacent marrow edema. When the diagnosis is uncertain, a nuclear medicine bone scan with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) can be used to look for signs of increased metabolism suggestive of abnormal stress.

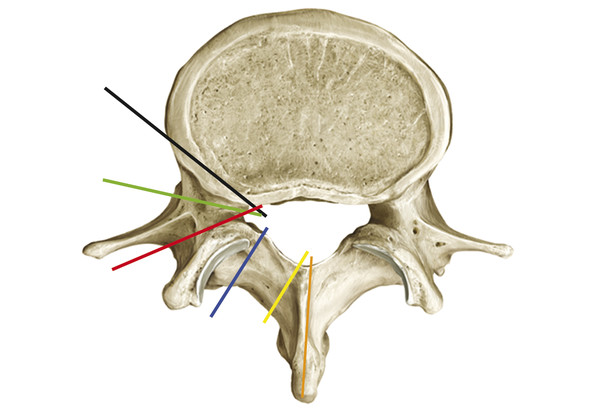

Other, more rare vertebral clefts than those of the posterior neural arch or pars interarticularis include a persistent neurocentral synchondrosis (Fig. 26.5), a retrosomatic cleft, a retroisthmic cleft, and a paraspinous cleft (Fig. 26.3), all of which are more common in the setting of multifocal anomalies of osseous segmentation.

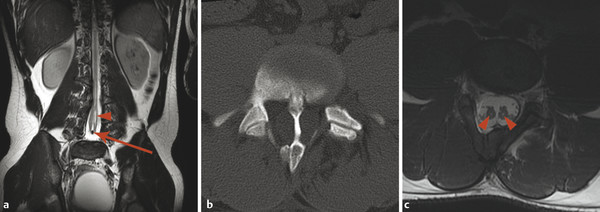

26.4 Diastematomyelia

A developmental anomaly that has a very interesting presentation both clinically and on imaging is diastematomyelia. This is a separation within the spinal canal that separates the thecal sac into two. The separation is typically partitioned by a septum, which may be fibrous or osseous. In diastematomyelia, the spinal cord is split into two, with each hemicord giving off a single ipsilateral pair of nerve roots (dorsal and ventral). A true cord duplication, in which each cord gives off right- and left-sided dorsal and ventral nerve roots, is exceedingly rare and is referred to as diplomyelia (Fig. 26.6). Diastematomyelia can present with symptoms of a tethered cord and with hydromyelia, both of which are discussed later in this chapter.

26.5 Sagittal Alignment

The sagittal alignment of the cervical vertebral column varies through childhood, starting with a kyphosis and progressing to a lordosis in young adulthood. Accordingly, a straightened alignment of the cervical vertebral column in an adolescent is normal, and should not be described as “loss of cervical lordosis,” and when seen with trauma does not necessarily indicate muscle spasm. Most children have a mild kyphosis in the thoracic spine and a mild lordosis in the lumbar spine. Altered alignment in one vertebral section can result in compensatory alterations in the alignment of other segments.

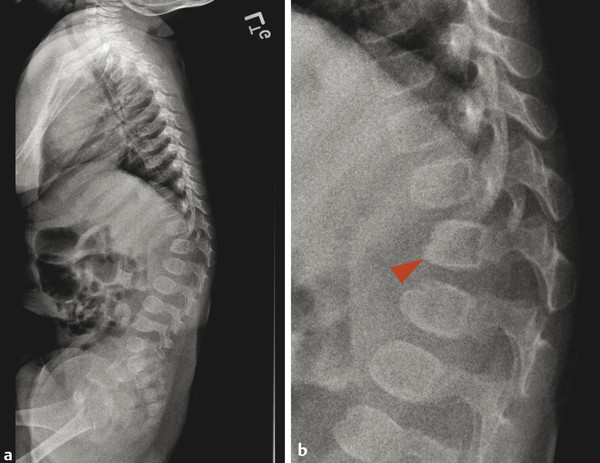

A congenital focal kyphosis can be present in the spine, commonly at the thoracolumbar junction, with a dysplastic vertebral body that demonstrates ventral “beaking.” This is known as a gibbus deformity and has both congenital and acquired etiologies (Fig. 26.7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree