27 Neoplasm

27.1 Spinal Neoplasm

Tumors of the spinal cord and vertebral column come in many varieties. The most common are primary tumors, but some metastatic lesions are also identified. In characterizing primary tumors, the differential considerations are based largely on location. The first differentiating feature is whether the origin of the tumor is intradural or extradural. Intradural tumors can be classified as being of intramedullary or extramedullary origin. Most tumors of the spinal cord and vertebral column can be put into one of these classifications, which allows a methodical approach to their characterization on imaging.

27.2 Intradural Intramedullary Neoplasms

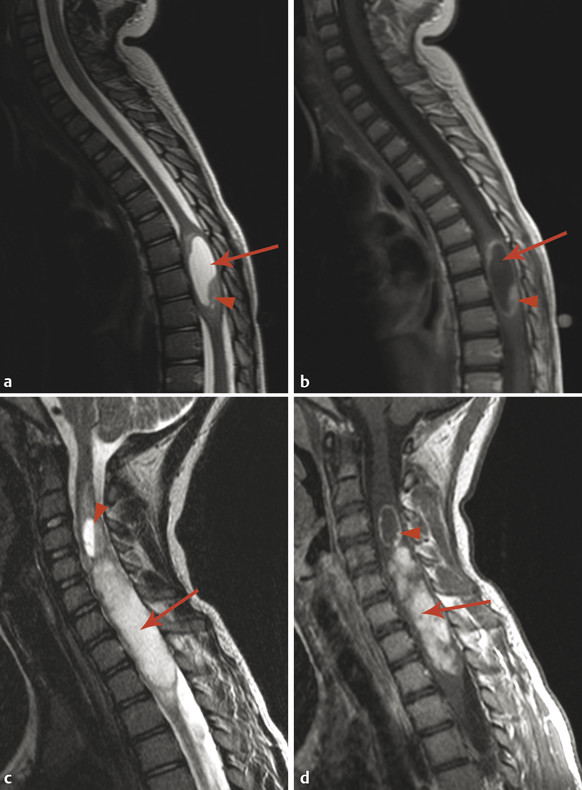

Intradural intramedullary tumors are those arising from the spinal cord itself. However, because the spinal cord is a part of the central nervous system (CNS), tumors of the cord are identical to many of those seen intracranially. The most common intramedullary spinal cord neoplasm (IMSCN) in children and adolescents is pilocytic astrocytoma (Fig. 27.1).

Pilocytic astrocytomas of the spinal cord can have features of cerebellar pilocytic astrocytomas, including contrast-enhancing solid nodular components and cystic areas. As with some pilocytic astrocytomas intrinsic to the brainstem, however, some such lesions of the spinal cord are predominantly solid. Pilocytic astrocytomas of the spinal cord are more likely to hemorrhage than those in the cerebellum, which can result in diagnostic confusion. In the literature on adult neoplasms, it is stated that ependymomas of the spinal cord are more likely to hemorrhage than are astrocytomas of the cord, and in the adult population this is true. However, there are several differences in the characteristics of these tumors in the pediatric and adult populations. In adults, astrocytomas tend to be fibrillary or anaplastic astrocytomas, or glioblastoma. In children, astrocytomas are nearly always pilocytic. Additionally, ependymomas are very rare in children, especially those younger than 15 years of age, unless there is a history of neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) (Fig. 7.10b).

Both ependymomas and pilocytic astrocytomas tend to be discrete lesions that displace nerve fibers of the cord, whereas the other types of astrocytomas (which are the only astrocytomas seen in adults) infiltrate such fibers. It is therefore possible to surgically resect pilocytic astrocytomas and ependymomas of the spinal cord, whereas astrocytomas that infiltrate the cord cannot be easily resected without disrupting neurologic functions. The relationship between a lesion and the fibers of the spinal cord has been suggested as a way in which diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) can be used to predict the histology of an IMSCN in adults; if an ependymoma is suspected, a resection may be done, whereas if an astrocytoma is suspected, biopsy may be preferred. In children, however, DTI likely plays an equally important role in determining the resectability of an IMSCN by revealing whether spinal cord fibers are displaced as opposed to being infiltrated by the IMSCN. But because pediatric astrocytomas are more commonly pilocytic astrocytomas, DTI is unlikely to be useful for predicting the histology of IMSCN in children. As noted earlier, age in the pediatric population generally predicts the histology of an IMSCN, which will only rarely be ependymoma. Nevertheless, ependymomas can occur in children, and particularly those who have NF2.

An additional IMSCN seen in children but not common in adults is ganglioglioma (Fig. 27.2). Gangliogliomas are low-grade tumors that have a tendency to infiltrate spinal cord fibers, possibly limiting the ability to safely resect these lesions while preserving cord function. Gangliogliomas of the cord in children tend to have fewer cystic areas than intracranial gangliogliomas, and are more likely to be eccentrically located within the cord than are pilocytic astrocytomas or ependymomas. Because they may be difficult to safely resect, it is fortunate that intramedullary gangliogliomas of the cord respond well to radiation therapy. Pilocytic astrocytomas of the spinal cord also respond well to radiation therapy, for which reason subtotal resection of these tumors is sometimes planned if it is difficult to differentiate tumor from cord tissue at the periphery of some lesions. The theory is that the residual tumor can be observed, and if necessary can be treated with repeat surgery or radiation therapy.

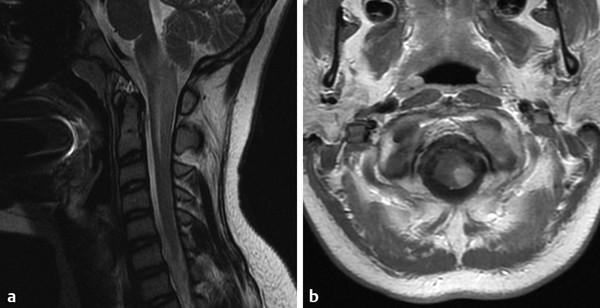

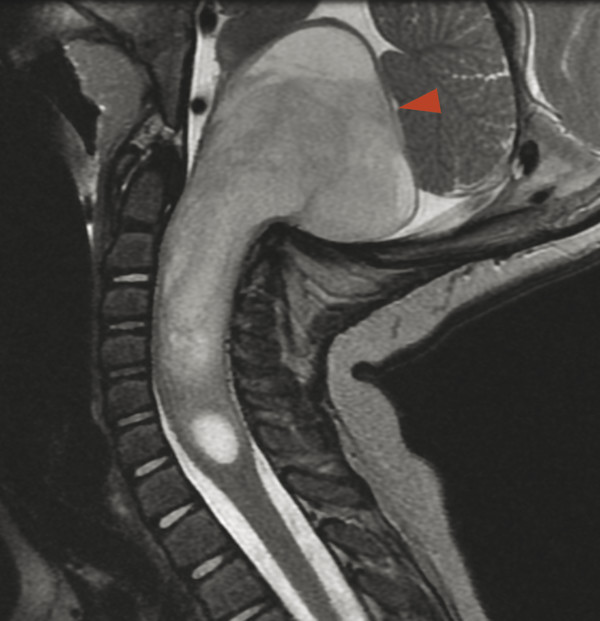

Intramedullary spinal cord neoplasms in the upper cervical cord have a propensity to grow superiorly across the cervicomedullary junction. Their growth along the craniocaudal axis is less restricted than in the transverse axis because there are few transversely oriented fibers to restrict this growth. When a tumor extends superiorly into the medulla oblongata, it is obstructed from extending more superiorly by the pyramidal and lemniscal decussations, and the medulla will focally enlarge (Fig. 27.3). From a treatment perspective, tumors of the craniocervical junction respond in the same way as IMSCN. 1

Patients with IMSCN resected from the cervical cord are at risk for the subsequent development of a kyphosis as the result of osseous and neuromuscular destabilization.

Hemangioblastomas are IMSCN that are highly vascular and can occur in a multifocal manner in patients with von Hippel–Lindau syndrome. It is important to be aware that the multifocal nature of these tumors does not indicate metastatic disease, and that each of the lesions of these tumors is instead the result of genetic predisposition.

It is important to recognize that some non-neoplastic conditions can mimic IMSCN. This is particularly true of noninfectious inflammatory conditions, such as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) and Devic’s syndrome/neuromyelitis optica, which are further discussed in Chapter 25.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree