Abdomen and Pelvis

William E. Brant

Imaging Methods

Conventional radiographs of the abdomen remain a mainstay for the assessment of the acute abdomen. CT, US, and MR provide comprehensive evaluation of the abdomen including the peritoneal cavity, retroperitoneal compartments, abdominal and pelvic organs, blood vessels, and lymph nodes.

Compartmental Anatomy of the Abdomen and Pelvis

Knowledge of the complex compartmental anatomy of the abdomen and pelvis is fundamental to understanding the effects of pathologic processes and to correctly interpret imaging studies. Understanding the shape and extent of anatomic compartments and their normal variations may clarify imaging findings that would otherwise be incomprehensible or lead to misdiagnosis (1). Fundamental considerations include constant anatomic landmarks, ligaments and fascia that define compartments, and normal variations in size and appearance of the various compartments and recesses. Identifying the precise compartment that an abnormality is in determines to a great extent the origin of the abnormality.

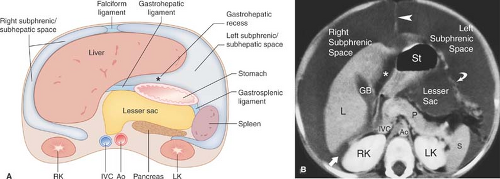

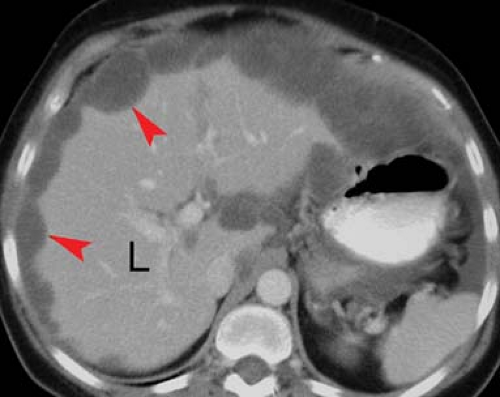

The peritoneal cavity is divided into the greater peritoneal cavity and the lesser peritoneal cavity (the lesser sac) (Fig. 25.1). Within both portions of the peritoneal cavity are numerous recesses in which pathological processes tend to loculate. The right subphrenic space communicates around the liver with the anterior subhepatic and posterior subhepatic space (Morison pouch). Morison pouch (the right hepatorenal fossa) is the most dependent portion of the abdominal cavity in a supine patient and it preferentially collects ascites, hemoperitoneum, metastases, and abscesses. The right subphrenic and subhepatic spaces communicate freely with the pelvic peritoneal cavity via the right paracolic gutter.

The left subphrenic space communicates freely with the left subhepatic space but is separated from the right subphrenic space by the falciform ligament and from the left paracolic gutter by the phrenicocolic ligament. The left subphrenic (perisplenic) space distends with fluid from ascites and with blood from splenic trauma. It is a common location for abscesses and for disease processes of the tail of the pancreas. The left subhepatic space (gastrohepatic recess) is affected by diseases of the duodenal bulb, lesser curve of the stomach, gallbladder, and left lobe of the liver.

Free fluid, blood, infection, and peritoneal metastases commonly settle in the pelvis because the pelvis is the most dependent portion of the peritoneal cavity in the upright patient and it communicates with both sides of the abdomen.

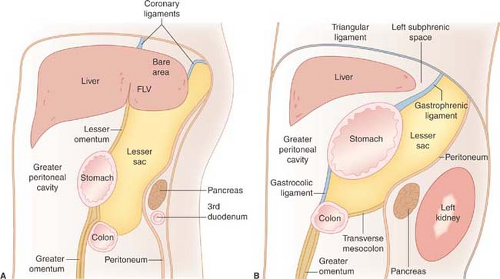

The falciform ligament consists of two closely applied layers of peritoneum extending from the umbilicus to the diaphragm in a parasagittal plane. The caudal free end of the falciform ligament contains the ligamentum teres, which is the remnant of the obliterated umbilical vein. Paraumbilical veins (portosystemic collateral vessels) that enlarge within the falciform ligament are a specific sign of portal hypertension. The reflections of the falciform ligament separate over the posterior dome of the liver to form the coronary ligaments, which define the bare area of the liver not covered by peritoneum. The coronary ligaments reflect between the liver and the diaphragm and prevent access of ascites and other intraperitoneal processes from covering the bare area of the liver.

The lesser omentum, composed of the gastrohepatic and hepatoduodenal ligaments, suspends the stomach and the duodenal bulb from the inferior surface of the liver. The lesser omentum separates the gastrohepatic recess of the left subphrenic space from the lesser sac (Figs. 25.1, 25.2). The lesser omentum transmits the coronary veins (which dilate as varices) and contains lymph nodes (which enlarge with involvement by gastric carcinoma and lymphoma). The lesser sac is the isolated peritoneal compartment between the stomach and the pancreas. It communicates with the rest of the peritoneal cavity (the greater sac) only through the small foramen of Winslow. Pathologic processes in the lesser sac usually occur because of disease in adjacent organs (pancreas, stomach) rather than spread from elsewhere in the abdominal cavity. The lesser sac is normally collapsed but can become huge when filled with fluid.

The greater omentum is a double layer of peritoneum that hangs from the greater curvature of the stomach and descends in front of the abdominal viscera, separating bowel from the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 25.2). The greater omentum

encloses fat and a few blood vessels. It serves as fertile ground for implantation of peritoneal metastases and assists in loculation of inflammatory processes of the peritoneal cavity such as abscesses and tuberculosis.

encloses fat and a few blood vessels. It serves as fertile ground for implantation of peritoneal metastases and assists in loculation of inflammatory processes of the peritoneal cavity such as abscesses and tuberculosis.

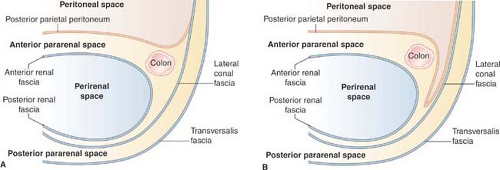

The retroperitoneal space between the diaphragm and the pelvic brim is divided into anterior pararenal, perirenal, and posterior pararenal compartments by the anterior and posterior renal fascia (Fig. 25.3). The anterior pararenal space extends between the posterior parietal peritoneum and the anterior renal fascia. It is bounded laterally by the lateroconal fascia. The pancreas, duodenal loop, and ascending and descending portions of the colon are within the anterior pararenal space. Disease in the

anterior pararenal space usually originates from these organs (pancreatitis, perforating/penetrating ulcer, diverticulitis).

anterior pararenal space usually originates from these organs (pancreatitis, perforating/penetrating ulcer, diverticulitis).

The anterior and posterior renal fasciae encompass the kidney, adrenal gland, and perirenal fat within the perirenal space. The anterior renal fascia is thin and consists of one layer of connective tissue. The posterior renal fascia is thicker, consisting of two layers of connective tissue (Fig. 25.3). The anterior layer of the posterior renal fascia is continuous with the anterior renal fascia. The posterior layer of the renal fascia is continuous with the lateroconal fascia, forming the lateral boundary of the anterior pararenal space. The anterior and posterior layers of the posterior renal fascia may be separated by inflammatory processes, such as pancreatitis, extending from the anterior pararenal space. The renal fascia is bound to the fascia surrounding the aorta and vena cava usually preventing spread of disease to the contralateral perirenal space. However, disease processes arising in the perivascular space, such as hemorrhage from aortic aneurysm rupture, may extend into the perirenal space. Fluid collections in the perirenal space are usually renal in origin (infection, urinoma, hemorrhage). Bridging septa extending between the renal fascia and the renal capsule tend to cause loculations of fluid processes in the perirenal space. The right perirenal space is open superiorly to the bare area of the liver, allowing spread of disease processes (infection, tumor) between the kidney and the liver.

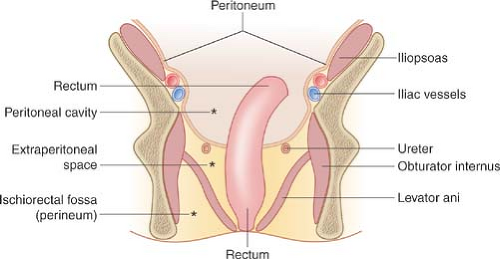

Figure 25.4. Compartmental Anatomy of the Pelvis. Diagram in the coronal plane illustrates the major anatomic compartments of the pelvis. |

The posterior pararenal space is a potential space, usually filled only with fat, extending from the posterior renal fascia to the transversalis fascia. The posterior pararenal fat continues into the flank as the properitoneal fat “stripe” seen on plain films of the abdomen. The compartment is limited medially by the lateral edges of the psoas and quadratus lumborum muscles. Isolated fluid collections are rare and most commonly caused by spontaneous hemorrhage into the psoas muscle as a result of anticoagulation therapy.

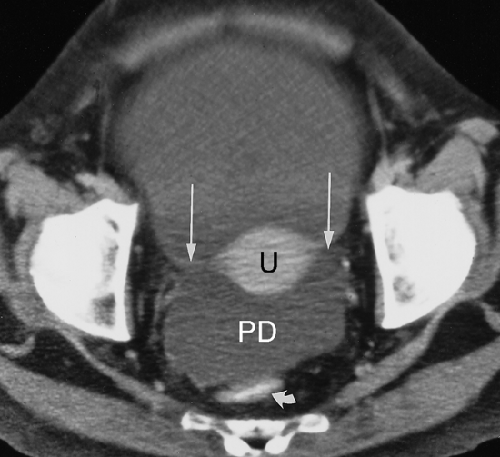

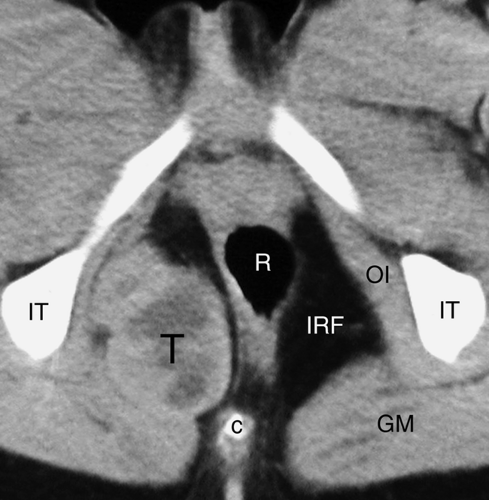

The pelvis is divided into three major anatomic compartments: peritoneal cavity, extraperitoneal space, and perineum (Fig. 25.4). The peritoneal cavity extends to the level of the vagina, forming the pouch of Douglas (cul-de-sac) in females (Fig. 25.5), or to the level of the seminal vesicles, forming the rectovesical pouch in males. The broad ligaments reflect over the uterus, fallopian tubes, and parametrial uterine vessels

and serve as the anterior boundary of the rectouterine pouch of Douglas. The cul-de-sac is the most dependent portion of the peritoneal cavity and collects fluid, blood, abscesses, and intraperitoneal drop metastases. The extraperitoneal space of the pelvis is continuous with the retroperitoneal space of the abdomen, extends to the pelvic diaphragm, and includes the retropubic space (of Retzius). Pathologic processes from the pelvis spread preferentially into the retroperitoneal compartments of the abdomen. The perineum lies below the pelvic diaphragm. The ischiorectal fossa serves as its anatomic landmark (Fig. 25.6).

and serve as the anterior boundary of the rectouterine pouch of Douglas. The cul-de-sac is the most dependent portion of the peritoneal cavity and collects fluid, blood, abscesses, and intraperitoneal drop metastases. The extraperitoneal space of the pelvis is continuous with the retroperitoneal space of the abdomen, extends to the pelvic diaphragm, and includes the retropubic space (of Retzius). Pathologic processes from the pelvis spread preferentially into the retroperitoneal compartments of the abdomen. The perineum lies below the pelvic diaphragm. The ischiorectal fossa serves as its anatomic landmark (Fig. 25.6).

Fluid in the Peritoneal Cavity

Fluid in the peritoneal cavity originates from many different sources and varies greatly in composition (2). Ascites is serous fluid in the peritoneal cavity most commonly caused by cirrhosis, hypoproteinemia, or congestive heart failure. Exudative ascites results from inflammatory processes such as abscess, pancreatitis, peritonitis, or bowel perforation. Hemoperitoneum results from trauma, surgery, or spontaneous hemorrhage. Neoplastic ascites is associated with intraperitoneal tumors. Urine, bile, and chyle may also spread freely within the peritoneal cavity.

Conventional radiographic diagnosis of ascites requires that at least 500 mL of fluid be present. Findings are (1) diffuse increase in density of the abdomen (gray abdomen), (2) indistinct margins of the liver, spleen, and psoas muscles, (3) medial displacement of gas-filled colon, liver, and spleen away from the properitoneal flank stripe, (4) bulging of the flanks, (5) increased separation of gas-filled small bowel loops, and (6) “dog’s ears” appearance of symmetric densities in the pelvis due to fluid spilling out of the cul-de-sac on either side of the bladder. CT demonstrates fluid density in the recesses of the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 25.1B, 25.5). The CT density of the fluid gives a clue as to its composition. Serous ascites has attenuation values near water (-10 to +10 H). Exudative ascites is usually above +15 H and acute bleeding into the peritoneal cavity averages +45 H. US is sensitive to small amounts of fluid in the peritoneal recesses. Care must be taken with US to examine the most gravity-dependent portions of the peritoneal cavity (Morison pouch and the pelvis). Simple ascites is anechoic, whereas exudative, hemorrhagic, or neoplastic ascites often contains floating debris. Septations in ascites are associated with an inflammatory or malignant process. MR shows limited specificity for defining the type of fluid present (2). Serous fluid is low signal intensity on T1WI and markedly increased in signal intensity on T2WI. Hemorrhagic fluid shows high signal intensity on both T1WI and T2WI. Serous ascites is commonly bright on gradient-echo images due to fluid motion.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (“jelly belly”) refers to gelatinous ascites that occurs as a result of intraperitoneal spread of mucin-producing cells resulting from rupture of appendiceal mucocele, intraperitoneal spread of benign or mucinous cysts of the ovary, or mucinous adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum (3). Conventional radiographs may demonstrate punctate or ringlike calcifications scattered through the peritoneal cavity. CT demonstrates mottled densities, septations, and calcifications within the fluid. The mucinous fluid is typically loculated and causes mass effect on the liver and bowel (Fig. 25.7). US demonstrates intraperitoneal nodules that range from hypoechoic to strongly echogenic.

Pneumoperitoneum

Free air within the peritoneal cavity is a valuable sign of bowel perforation, most commonly caused by duodenal or gastric ulcer perforation. However, additional causes of pneumoperitoneum include trauma, recent surgery or laparoscopy, and infection of the peritoneal cavity with gas-producing organisms. Postoperative pneumoperitoneum usually resolves in 3 to 4 days. Serial images demonstrate a progressive decrease in the

amount of air present. Failure of progressive resolution, or an increase in the amount of air present, suggests a leak of bowel anastomosis or sepsis. Pneumoperitoneum in the absence of a ruptured viscus may occur with air introduced through the female genital tract by orogenital insufflation or in association with pulmonary emphysema, alveolar rupture, and dissection of air into the peritoneal cavity.

amount of air present. Failure of progressive resolution, or an increase in the amount of air present, suggests a leak of bowel anastomosis or sepsis. Pneumoperitoneum in the absence of a ruptured viscus may occur with air introduced through the female genital tract by orogenital insufflation or in association with pulmonary emphysema, alveolar rupture, and dissection of air into the peritoneal cavity.

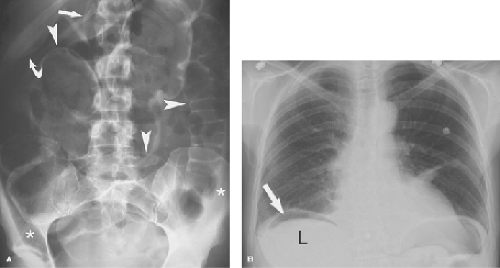

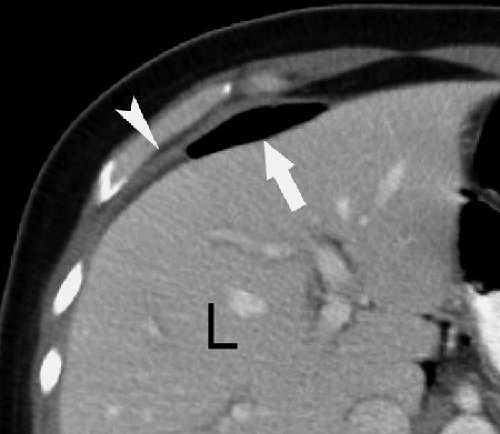

Conventional radiographs show pneumoperitoneum best on images obtained with the patient in the standing or sitting position. Upright chest radiographs are the most sensitive for free air. Small amounts of air are clearly demonstrated beneath the domes of the diaphragm. Left lateral decubitus and cross-table lateral views may be used with very ill patients to demonstrate air outlining the liver. Signs of pneumoperitoneum on supine radiographs (Fig. 25.8) include the following (4): (1) gas on both sides of the bowel wall (Rigler sign), (2) gas outlining the falciform ligament, (3) gas outlining the peritoneal cavity (the “football sign”), and (4) triangular or linear localized extraluminal gas in the right upper quadrant. On CT, small amounts of extraluminal gas may be confused with gas within the bowel and can be surprisingly difficult to recognize. Images should be examined at lung windows to detect free intraperitoneal air. The peritoneal recess between the liver and the diaphragm (Fig. 25.9) is a good place to look for pneumoperitoneum on CT.

Abdominal Calcifications

Intra-abdominal calcifications may be an important sign of intra-abdominal disease and should be searched for on every imaging study of the abdomen. CT and US are more sensitive to detection of calcifications than are conventional radiographs. However, the high spatial resolution of conventional radiography commonly provides characteristic findings that allow a specific diagnosis of the nature of the calcification (5).

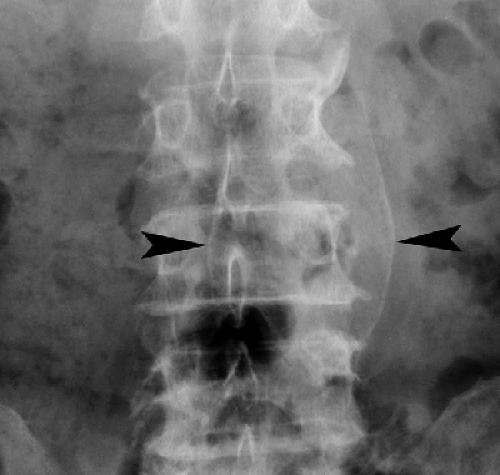

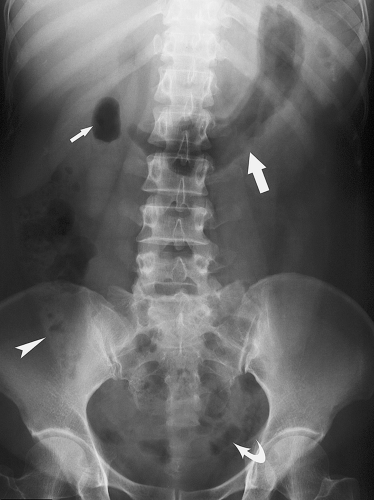

Vascular calcifications are common in the aorta and iliac vessels (see Fig. 25.13) of older individuals. Plaque-like

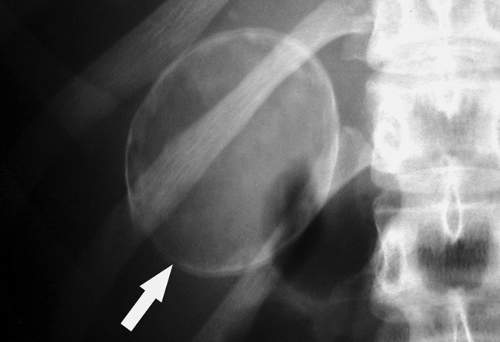

vascular calcifications overlie the lumbar spine and sacrum and commonly require detailed inspection to detect. Aneurysms of the aorta are manifest by luminal diameter exceeding 3 cm as measured between calcifications in the aortic wall (Fig. 25.10). Ringlike calcified aneurysms most commonly involve the splenic or renal arteries. Phleboliths are calcified thrombi in veins most commonly visualized in the lateral aspects of the pelvis. They are round or oval calcifications up to 5 mm in size that commonly contain a central lucency. They may be mistaken for urinary tract calculi.

vascular calcifications overlie the lumbar spine and sacrum and commonly require detailed inspection to detect. Aneurysms of the aorta are manifest by luminal diameter exceeding 3 cm as measured between calcifications in the aortic wall (Fig. 25.10). Ringlike calcified aneurysms most commonly involve the splenic or renal arteries. Phleboliths are calcified thrombi in veins most commonly visualized in the lateral aspects of the pelvis. They are round or oval calcifications up to 5 mm in size that commonly contain a central lucency. They may be mistaken for urinary tract calculi.

Calcified lymph nodes result most commonly from granulomatous diseases such as tuberculosis or histoplasmosis. The calcification is usually mottled and 10 to 15 mm in size. Mesenteric nodes are the most commonly calcified.

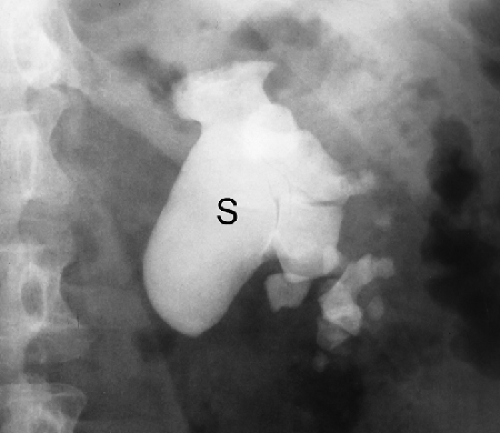

Gallstones and Gallbladder. Only about 15% of gallstones contain sufficient calcium to be identified on conventional radiography. Most calcified gallstones contain calcium bilirubinate and have a laminated appearance with a dense outer rim and more radiolucent center. When multiple gallstones are present, they are commonly faceted. Calcifications in the gallbladder wall (porcelain gallbladder) (Fig. 25.11) are plaque-like and oval in configuration conforming to the size and shape of the gallbladder. Milk of calcium bile is a suspension of radiopaque crystals within gallbladder bile. Layering of the suspension can be demonstrated on erect radiographs.

Urinary Calculi. About 85% of urinary calculi are visible on conventional radiographs. They range in size from punctate up to several centimeters. Most characteristic are the staghorn calculi, which assume the shape of the renal collecting system (Fig. 25.12). Renal calculi are differentiated from gallstones on radiographs by oblique projections that confirm their posterior position, as opposed to the more anterior positions of gallstones. Ureteral calculi may be seen anywhere along the course of the ureter but are most common at the areas of narrowing: the ureteropelvic junction, the pelvic brim, and the vesicoureteral junction. Bladder calculi (Fig. 25.13) are single or multiple, commonly laminated, may be any size, and usually lie near the midline of the pelvis. Calculi within bladder diverticula may be eccentric to the bladder. CT has become the imaging method of choice to document urinary tract stones.

Liver and spleen granulomas are usually multiple, small, and dense. They are healed foci of tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, or other granulomatous disease.

Appendicoliths and enteroliths are concretions within the lumen of the bowel. Most are round or oval and have concentric laminations. Appendicoliths are strongly indicative of acute appendicitis in patients presenting with acute abdominal pain. Enteroliths are most common in the colon and often result from calcium deposition on an undigestible material such as a fruit pit.

Calcified adrenal glands are associated with adrenal hemorrhage in the newborn, tuberculosis, and Addison disease. The calcification is mottled and in the location of the adrenal glands on either side of the first lumbar vertebra (Fig. 25.14).

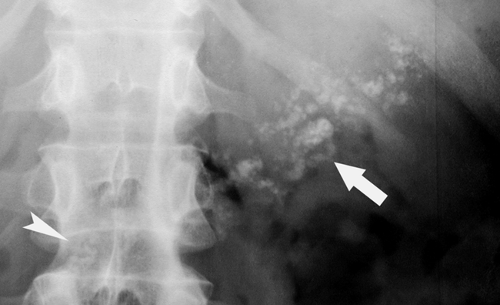

Pancreatic calcification is associated with chronic alcohol-induced pancreatitis and hereditary pancreatitis. The calcifications are due to pancreatic calculi and are usually coarse and of varying size (Fig. 25.15).

Calcified cysts may be found in the kidneys, spleen, liver, appendix, and the peritoneal cavity. Calcification in the wall of a cyst is curvilinear or ring-shaped (Fig. 25.16). Echinococcus cysts commonly calcify and may be found in any intra-abdominal organ as well as within the peritoneal cavity.

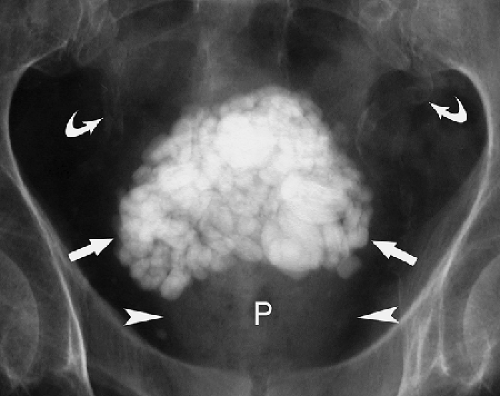

Tumor Calcification. A wide variety of different tumors of abdominal organs may contain calcifications. The coarse “popcorn” calcifications of uterine leiomyomas are most characteristic. Benign cystic teratomas may form teeth or bone. Calcified peritoneal metastases of ovarian or colon mucinous cystadenocarcinoma may outline the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 25.17). Renal cell carcinoma calcifies in up to 25% of cases.

Soft tissue calcifications may be seen with hypercalcemic states, idiopathic calcinosis, and old hematomas. Calcified injection granuloma from quinine, bismuth, and calcium salts of penicillin is commonly evident in the buttocks. Cysticercosis causes characteristic “rice-grain” calcifications in muscles.

Bowel contents may include bone, pits, seeds, birdshot, or medications containing iron or other heavy metals that result in abdominal opacities.

Peritoneal calcifications may be nodular or sheetlike and result most commonly from peritoneal dialysis, previous peritonitis, or peritoneal carcinomatosis (Fig. 25.17).

Acute Abdomen

The differential diagnosis of patients presenting with acute abdominal pain is extremely broad (Table 25.1). Accurate and efficient diagnosis requires cooperation between the referring physician and the radiologist to select the imaging method

most likely to provide the correct diagnosis. Routine assessment of the acute abdomen commonly includes the “acute abdomen series,” which consists of an erect posterior–anterior chest radiograph and supine and erect or decubitus radiographs of the abdomen. The chest radiograph provides optimal detection of pneumoperitoneum and intrathoracic diseases that may present with abdominal complaints. The supine abdominal film permits diagnosis of many acute abdominal conditions, and the horizontal-beam abdominal film adds confidence to the diagnosis. CT or US is routinely obtained to provide a definitive diagnosis.

most likely to provide the correct diagnosis. Routine assessment of the acute abdomen commonly includes the “acute abdomen series,” which consists of an erect posterior–anterior chest radiograph and supine and erect or decubitus radiographs of the abdomen. The chest radiograph provides optimal detection of pneumoperitoneum and intrathoracic diseases that may present with abdominal complaints. The supine abdominal film permits diagnosis of many acute abdominal conditions, and the horizontal-beam abdominal film adds confidence to the diagnosis. CT or US is routinely obtained to provide a definitive diagnosis.

Figure 25.16. Calcified Renal Cyst. Conventional radiograph shows the rim calcification (arrow) characteristic of wall calcification in a renal cyst. |

Normal Abdominal Gas Pattern. Interpretation of conventional abdominal radiographs routinely includes assessment of gas, fluid, soft tissue, fat, and calcium densities. Normal gas in the abdomen is predominantly swallowed air (Fig. 25.18). Air–fluid levels are seen in normal patients, commonly in the stomach, often in the small bowel, but never in the colon distal to the hepatic flexure. Normal air–fluid levels in the small bowel should not exceed 2.5 cm in length. Small bowel gas usually appears as multiple small, random gas collections scattered throughout the abdomen (6). Small bowel gas is increased in patients who chronically swallow air or drink carbonated beverages. A normal intestinal gas pattern varies from no intestinal gas to gas within three to four variably shaped small intestinal loops measuring less than 2.5 to 3 cm in diameter. The normal colon contains some gas and fecal material and varies in diameter from 3 to 8 cm, with the cecum having the largest diameter. Complete absence of gas in the small bowel may be seen in patients with bowel obstruction with fluid rather than air filling the dilated bowel loops. The term “nonspecific abdominal gas pattern” has no precise meaning and should not be used.

Table 25.1 Common Causes of Acute Abdomen | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Dilated Bowel. Small bowel is dilated when it exceeds 2.5 to 3.0 cm in diameter. The colon is dilated when it exceeds 5 cm in diameter, and the cecum is dilated when it exceeds 8 cm in diameter. In adults, dilated small bowel can usually be differentiated from dilated large bowel by assessment of location and anatomic features. Small bowel is more central in the abdomen and is characterized by valvulae conniventes, which cross the entire diameter of the lumen. Dilated small bowel rarely exceeds 5 cm in diameter, although large bowel is not considered dilated until it exceeds 5 cm in diameter. Large bowel is

more peripheral in the abdomen and is characterized by haustra that extend only part way across the lumen. Large bowel contains fecal material that has a characteristic mottled appearance. The cecum, which has the largest normal diameter of the large bowel, always dilates to the greatest extent irrespective of the site of obstruction.

more peripheral in the abdomen and is characterized by haustra that extend only part way across the lumen. Large bowel contains fecal material that has a characteristic mottled appearance. The cecum, which has the largest normal diameter of the large bowel, always dilates to the greatest extent irrespective of the site of obstruction.

Table 25.2 Common Causes of Adynamic Ileus | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Adynamic Ileus. The word “ileus” means stasis and does not differentiate mechanical obstruction from nonmechanical stasis. The terms “adynamic ileus,” “paralytic ileus,” and “nonobstructive ileus” are used interchangeably and refer to stasis of bowel contents because of decreased or absent peristalsis. Common causes of adynamic ileus are listed in Table 25.2. Adynamic ileus typically demonstrates diffuse symmetric, predominantly gaseous, distension of bowel. The small bowel, stomach, and colon are proportionally dilated without an abrupt transition. More bowel loops are dilated than with obstruction. Occasionally, adynamic ileus may result in a gasless abdomen with dilated loops of bowel that are filled only with fluid. US is useful in confirming decreased or absent peristalsis, although examination may be difficult if large amounts of gas are present.

Sentinel loop refers to a segment of intestine that becomes paralyzed and dilated as it lies next to an inflamed intra-abdominal organ. In essence, it is a short segment of adynamic ileus that appears as an isolated loop of distended intestine that remains in the same general position on serial images (Fig. 25.19). A sentinel loop alerts one to the presence of an adjacent inflammatory process. A sentinel loop in the right upper quadrant suggests acute cholecystitis, hepatitis, or pyelonephritis. In the left upper quadrant, pancreatitis, pyelonephritis, or splenic injury may be suspected. In the lower quadrants, diverticulitis, appendicitis, salpingitis, cystitis, or Crohn disease is the cause of a sentinel loop.

Toxic megacolon is a manifestation of fulminant colitis characterized by extreme dilation of all or a portion of the colon. In this state, peristalsis is absent and the large bowel loses all tone and contractility. The patient has progressive abdominal distension and is toxic, febrile, and obtunded. Bowel sounds and bowel movements are absent. The bowel wall becomes like “wet blotting paper,” and the risk of perforation is extreme. Mortality approaches 20% in toxic megacolon. Acute ulcerative colitis is the most common cause of toxic megacolon (Table 25.3). Conventional radiographs demonstrate distension of the colon with absent haustra. Dilation of the transverse colon up to 15 cm diameter is often the most striking finding. The diagnosis is suggested when the diameter of the colon exceeds 5 cm and the mucosa appears abnormal (Fig. 25.20). Pseudopolyps due to islands of edematous mucosa surrounded by extensive ulceration appear as soft tissue nodules within the air-distended colon. CT demonstrates a distended colon filled with air and fluid. The wall of the colon is thin but has an irregular nodular contour; air may be seen within the colon wall. Barium enema is absolutely contraindicated because of risk of perforation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree