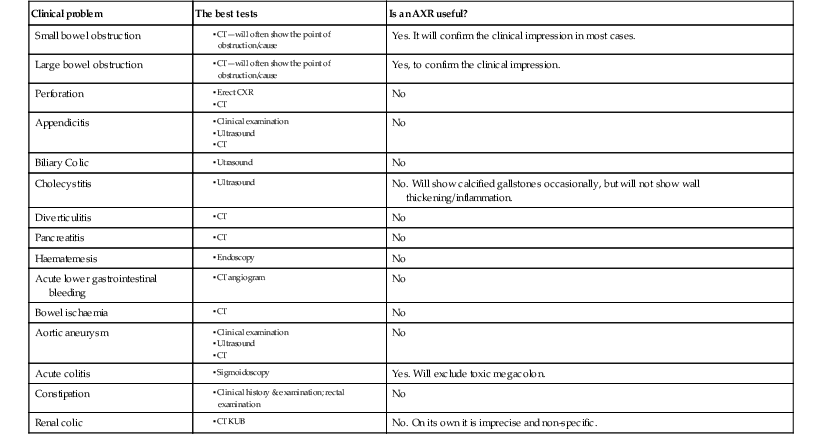

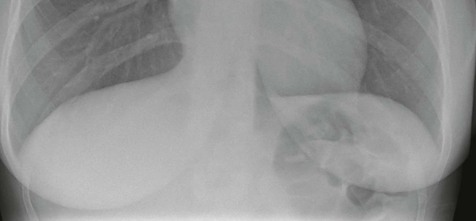

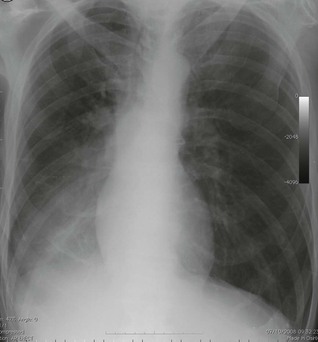

A patient with abdominal trauma does not require a plain abdominal radiograph (AXR). The AXR will not contribute to the clinical diagnosis and should be avoided. The AXR is of limited value as a diagnostic tool in the evaluation of many patients presenting with an acute abdomen. This is largely because the abdominal contents are composed of soft tissue. Plain film radiography does not provide adequate soft tissue contrast discrimination to detect and differentiate between many of the numerous inflammatory and neoplastic intra-abdominal soft tissue pathologies. The AXR is not the right tool for the job. Consequently, it has been superseded by ultrasound and CT scanning which are highly accurate in terms of evaluating the various intra-abdominal soft tissues. In present day clinical practice, the AXR is in the main limited to confirming a clinical suspicion of large or small bowel obstruction (as illustrated below), and demonstrating dangerous swallowed foreign bodies. Even so, CT will be selected as the first line imaging test in many cases of suspected intestinal obstruction, and also as the preferred and only imaging examination when renal colic is suspected. What if the preferrred imaging investigations are not immediately available? Is there any point in requesting an AXR as a substitute imaging test? On the whole, no. You risk obtaining false reassurance from a seemingly normal AXR appearance. It is safer to rely on a detailed clinical history and a careful physical examination. Furthermore, an experienced pair of examining hands from a member of the surgical team will recognise the emergency case that needs to go to theatre. The table on the right indicates the relatively few occasions when an AXR can be useful.

Abdominal pain & abdominal trauma

The AXR—its usefulness

Abdominal pain & abdominal trauma

19