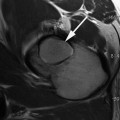

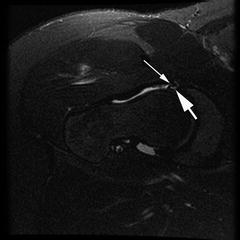

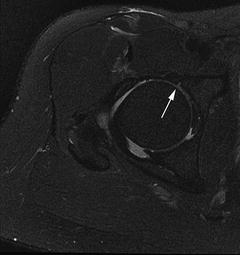

Fig. 7.1

Sublabral sulcus. Posterior sublabral sulcus (thin arrow) (axial PD arthrogram images)

Studler et al. have described the presence of a sublabral sulcus located in the anterior hip, which makes the distinction between the sulcus and a tear more difficult [15]. However, the anterior sublabral sulcus and labral tears can be differentiated by location and appearance. Using a clock face with 12 o’clock located superiorly toward the head of the patient, 3 o’clock posterior, 6 o’clock inferior, and 9 o’clock anterior, the anterior sublabral sulcus occurs at the 8 o’clock position most commonly (located within the anteroinferior quadrant). Defects occurring at the 9 o’clock and 10 o’clock positions (in the anterosuperior quadrant) are more typical for labral tears, which helps with the distinction. In addition, the sublabral sulcus is typically smooth, without contrast material extending into the substance of the labrum or across the entire labral base with MRa. There is no associated cartilage loss, labral signal abnormality, underlying osseous lesion, or para-labral cyst seen in conjunction with sublabral sulci, while these are common findings associated with labral tears [15].

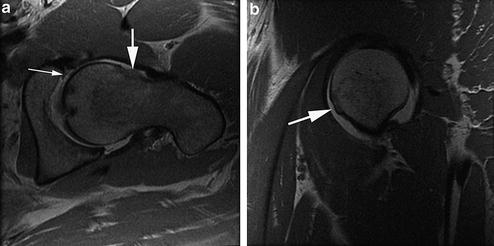

There is also a normal perilabral recess, occurring between the labrum and the overlying joint capsule, which can become distended with contrast material during MRa [6, 12] (Fig. 7.2). However, given its location, superficial to the chondrolabral junction, mistaking this normal variant for a tear would be unlikely.

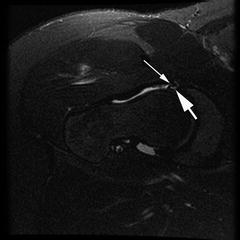

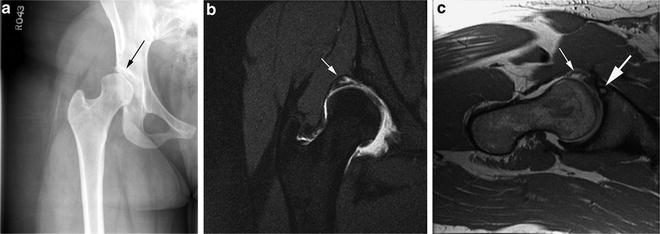

Fig. 7.2

Normal variant perilabral recess (thin white arrow) between the joint capsule and the underlying labrum. Tear of the underlying acetabular labrum is also present (thick arrow) (axial PD arthrogram image)

Absence of the labrum. Early MR imaging of the pediatric and adult hip demonstrated certain patients with complete absence of the labrum, thought to be a congenital variant [6]. However, these early studies used MR scanners with lower resolution and larger slice thickness than used in current imaging techniques. Furthermore, older MR imaging of the labrum was done without intra-articular contrast material, which greatly aids in evaluating the acetabular labrum. Findings of congenitally absent labra were likely the result of early imaging limitations, rather than true abnormalities.

The labrum becomes more heterogeneous with age, demonstrating increased signal intensity and irregular morphology. Apparent absence of the labrum in the older population is likely a result of significant degenerative change and tearing, as opposed to congenital absence.

Labral tears. Tears of the acetabular labrum can be associated with the development of cartilage loss, progressive cartilage damage, and subsequent development of osteoarthrosis. When it occurs, this process is initiated by shear forces or impingement within the hip causing excessive loading of the labrum. Inciting pathology includes acetabular dysplasia or morphology associated with FAI. Initial shear forces or impingement may then result in fraying of the acetabular labrum along its articular margin, progressing to labral tearing at the chondrolabral junction. Delamination of the articular cartilage may then occur, resulting in cartilage flaps at the level of the labral abnormality, leading to further progression of labral and chondral degeneration, and, eventually, osteoarthrosis [16, 17].

When evaluating the acetabular labrum with MRa, the labrum should be assessed for its morphology, the presence of abnormal signal, the presence of contrast material within an adjacent cleft/defect, as well as the presence of contrast material extending into the labrum itself, or across the entire labral base. Care must be taken to distinguish perilabral recess and sublabral sulcus, which are normal findings, from true labral tears.

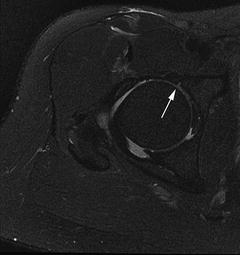

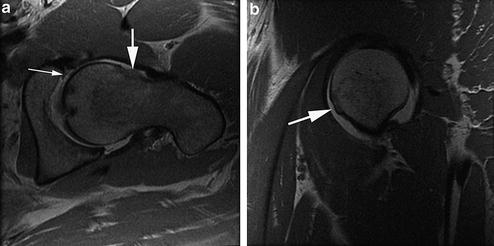

Labral tears and associated cartilage lesions occur most commonly in the anterosuperior quadrant of the hip, and may be of partial or full thickness [12] (Figs. 7.3 and 7.4), with occasional extension into other quadrants. Concurrent labral tears at multiple sites are seen relatively infrequently, and have been reported only 7 % of the time [12]. When this occurs, the tears typically occur anteriorly and posteriorly. The posterior tear is thought to represent a countre-coup injury secondary to the change in biomechanics of the hip caused by the anterior tear [12]. Isolated posterior labral tears in the Western population most commonly occur in the setting of trauma and posterior hip dislocation [18]. However, a higher incidence of non-traumatic posterior labral tears has been reported in Japan, possibly due to the increased amounts of time spent squatting or sitting on the floor [12, 19].

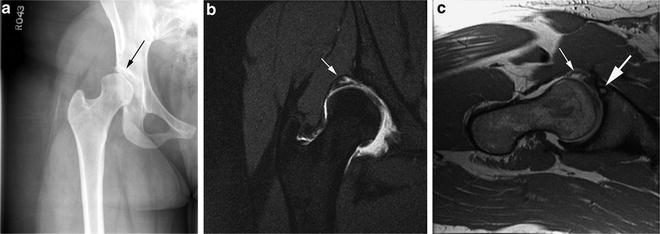

Fig. 7.3

Full-thickness labral tear at the chondrolabral junction. (a) Labral tear (thin white arrow) in the setting of FAI. Note the prominent osseous excrescence at the femoral head–neck junction (short thick white arrow). (b) Prominent osseous excrescence of the femoral head–neck junction (thick white arrow) is seen in sagittal plane (axial T2 and sagittal PD arthrogram images)

Fig. 7.4

Partial thickness labral tear—small partial defect at the chondrolabral junction (white arrow). Axial T2 fat-saturated arthrogram image

Labral tears occur most commonly at the chondrolabral junction and are often described as labral detachments. Histologically, this type of tear occurs at the transition zone between the fibrocartilage of the labrum and the underlying hyaline articular cartilage [19]. Tears confined to the substance of the labrum, occurring along the course of the circumferentially oriented fibers, are less common [12]. Histologically, these types of tears involve cleavage planes of variable depths within the substance of the labrum, perpendicular to the internal surface of the labrum [19].

Acute tears. Classically, labral tears in the setting of trauma have been described with posterior hip dislocations. Transverse acetabular fractures are associated with avulsion of the labrum from the acetabular rim [12]. More commonly, labral tears occur in the setting of repetitive micro-trauma at extremes of motion in certain athletes. Soccer, hockey, golf, martial arts, and ballet involve extremes of abduction, extension, flexion, and external rotation, and have been associated with labral tears [19]. The most common movement associated with acute labral tears is hyperextension with concurrent external rotation. In this position, the labrum is subject to increased strain and the forces that are transmitted across the labrummay result in a tear. Damage to the adjacent hyaline cartilage is the most common associated injury seen in the setting of a labral tear [19].

Femoroacetabular impingement. FAI has been characterized as abutment of the proximal femoral head–neck junction with the anterosuperior acetabulum. FAI can be classified as CAM type (osseous excresence at the femoral head–neck junction), pincer type (overcoverage of the femoral head by the acetabulum), or mixed. Impingement between the proximal femur and acetabulum damages the interposed labrum and cartilage and has been associated with the development of osteroarthrosis.

Developmental hip dysplasia. Patients with DDH are prone to distinct labrochondral and acetabular pathology, known as the “acetabular rim syndrome,” described by Klaue [20]. There are two subtypes of acetabular rim syndrome. Type I involves a shallow and vertically oriented acetabulum, with an incongruent femoral head. This incongruence shifts the weight-bearing load to the labrum resulting in shear stresses across the labrum and secondary hypertrophy and separation from the adjacent acetabulum (Fig. 7.5). In this situation, para-labral cysts may form, which should alert the clinician to the possibility of an underlying labral tear [13].

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Fig. 7.5

Developmental hip dysplasia. (a

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree