Acetabular labral tears are a mechanical cause of hip pain. Hip MR imaging should be performed on 1.5-T or 3-T magnets using small field-of-view and high-resolution imaging. The following should be used in the assessment for labral tear abnormalities on MR arthrography: labral morphology and contrast extension into the labral substance or between the labral base and acetabulum. Description of the labral tear and extent of tear is useful for hip arthroscopists. Understanding the pitfalls around the acetabular labral complex helps avoids misinterpretation of labral tears.

Key Points

- •

MR arthrography is the imaging technique of choice for evaluation of labral pathology.

- •

Intra-articular anesthetic injection at the time of MR arthrography is key to many ordering providers in determining if hip pain is related to an intra-articular cause and helps guide treatment.

- •

Using all MR imaging planes aids in detection of labral tears.

Introduction

The acetabular labrum is an important structure within the hip that is believed to provide joint stability, although the exact role of the labrum continues to be studied. Labral pathology is a known cause of hip pain in the active population. Labral abnormalities are associated with femoroacetabular impingement and are a significant factor in the development and progression of degenerative joint disease. Those patients with labral abnormalities may have acute or chronic symptoms of widely ranging intensities, locations, and duration. Clinical findings are highly variable, and numerous regional anatomic structures can make the clinical evaluation difficult. Demands for improved diagnosis of hip conditions continue with several advanced imaging techniques, including MR imaging, MR arthrography, CT arthrography, and sonography ( Box 1 ). This article reviews the normal anatomy, imaging techniques, imaging findings, pathology, and pitfalls in the assessment of the acetabular labrum.

- •

Early diagnosis and treatment of acetabular labral tear is important to help provide pain relief and may prevent the early onset of osteoarthritis.

- •

MR arthrography is the imaging technique of choice for the detection of acetabular labral tears.

Introduction

The acetabular labrum is an important structure within the hip that is believed to provide joint stability, although the exact role of the labrum continues to be studied. Labral pathology is a known cause of hip pain in the active population. Labral abnormalities are associated with femoroacetabular impingement and are a significant factor in the development and progression of degenerative joint disease. Those patients with labral abnormalities may have acute or chronic symptoms of widely ranging intensities, locations, and duration. Clinical findings are highly variable, and numerous regional anatomic structures can make the clinical evaluation difficult. Demands for improved diagnosis of hip conditions continue with several advanced imaging techniques, including MR imaging, MR arthrography, CT arthrography, and sonography ( Box 1 ). This article reviews the normal anatomy, imaging techniques, imaging findings, pathology, and pitfalls in the assessment of the acetabular labrum.

- •

Early diagnosis and treatment of acetabular labral tear is important to help provide pain relief and may prevent the early onset of osteoarthritis.

- •

MR arthrography is the imaging technique of choice for the detection of acetabular labral tears.

Normal anatomy

The acetabular labrum is a fibrocartilagenous structure that is located circumferentially around the acetabular perimeter and attaches to the transverse acetabular ligament posteriorly and anteriorly. The acetabular labrum is attached to the perimeter of the acetabular hyaline cartilage. The appearance of a cleft or sulcus can often be seen between the labrum and transverse ligament where they join. The labrum is primarily composed of circumferential type I collagen fibers. The labrum is triangular in cross-section, with a base approximately 4.7 mm wide at the osseous attachment by approximately 4.7 mm tall. The medial extent of the labrum from the acetabular rim varies by subject and location within the acetabulum.

The labrum is innervated by nerves that play a role in proprioception and pain production. The vascular supply to the labrum is from capsular blood vessels that are derived from the obturator, superior gluteal, and inferior gluteal arteries. The labral substance blood supply is from small vessels along the capsular side of the labrum. The vessels do not penetrate deeply, which limits the blood supply such that the majority of the labrum is avascular and, therefore, an injured labrum has limited potential to heal. The healing potential is greatest at the peripheral capsulolabral junction, where the blood supply is greatest, an important factor when considering whether a labral tear is repairable.

The labrum is believed to have several important functions, including the containment of the femoral head during acetabular formation and stabilization of the hip by deepening the acetabulum and maintaining hip joint congruity. The hip joint is subject to a large transmitted load. The acetabular labrum is placed under undue stress in conditions where the morphology of the hip is abnormal, such as in developmental dysplasia and femoroacetabular impingement. Biomechanical studies have shown that the labrum aids in sealing the hip joint and preventing the expression of fluid when the joint is stressed. This sealing effect is believed to offer cartilage protection within the hip joint. The labrum is not designed to withstand significant weight-bearing forces; when subjected to such forces, it eventually degenerates and tears.

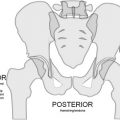

The normal anatomy of the hip has been reviewed earlier within this issue by Chang and Huang. The relationship of the joint capsule and the iliopsoas tendon with the acetabular labrum is discussed in this article. The proximal attachment of the capsule of the hip joint is along the osseous rim of the acetabulum. Typically, the capsule inserts near the base of the labrum, creating the perilabral recess. Anteriorly and posteriorly, the capsule courses further away from the acetabular margin and the recess is deeper, particularly anteriorly. The capsule attaches distally along the anterior aspect of the femoral neck at the base of the trochanters. A series of ligaments helps reinforce the capsule and the iliofemoral, ischiofemoral, and pubofemoral ligaments. There is also a circular layer of fibers along the deep surface of the joint capsule at the base of the femoral neck, called the zona orbicularis. The iliopsoas tendon is closely related to the anterior aspect of the hip joint and lies adjacent to the anterior aspect of the acetabular labrum at the level of the acetabular rim.

Clinical presentation

Diagnosis of acetabular labral tears can be difficult and they are a known cause of mechanical hip pain. Labral tears can be seen in patients with femoroacetabular impingement (see article by Bredella and colleagues in this issue discussing femoroacetabular impingement), hip dysplasia, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, osteoarthritis, and trauma. Labral tears often occur in young patients with normal radiographs and no history of prior trauma. More recently, iliopsoas impingement has been identified as a cause of labral pathology. Athletic activities that involve repetitive pivoting movements or repetitive hip flexion are recognized as additional causes of acetabular labral injury, and tears of the acetabular labrum have become increasingly recognized disorder in young adult and middle-aged patients. Labral tears as the culprit for hip pain may be due to the increasing recognition of changes associated with femoroacetabular impingement. The mechanism of injury is commonly reported as a sudden twisting or pivoting motion, with a pop, click, catching, or locking sensation. More commonly, the symptom presentation is subtle, characterized by dull activity-induced or positional pain that fails to improve over time. Patients may describe a deep discomfort within the anterior groin or lateral hip pain proximal to the greater trochanter or posteriorly. A clicking mechanical symptom may suggest an acetabular labral tear although other entities, such as snapping iliopsoas tendon, may give a similar presentation.

The impingement test, in which the hip is flexed to 90° with maximum internal rotation and adduction, may produce pain and is associated with intra-articular hip pain; it is useful for diagnosis of femoroacetabular impingement and potentially associated with labral pathologic conditions. The labral stress test, in which the hip is brought into flexion, abduction, and external rotation and then extended as the extremity is adducted and internally rotated, may reproduce pain and/or cause a clunk of a labral tear. Together, the clinical and imaging tests help diagnose labral pathology. Early diagnosis and treatment of acetabular labral tear are important because they not only provides pain relief but may prevent the early onset of osteoarthritis.

Imaging technique

MR imaging remains the imaging technique of choice in the evaluation of the acetabular labrum. Both conventional MR imaging and MR arthrography are commonly used to diagnose internal derangements of the hip joint. Hip MR imaging is best performed on 1.5-T or 3-T magnets because higher field strength provides a higher intrinsic signal-to-noise ratio, which is critical for high-resolution imaging. Hip imaging should be performed with either a surface phased array coil or a multiple channel, cardiac coil.

Conventional MR Imaging

Conventional MR imaging of the hip with small field-of-view (14–16 cm) and high-resolution imaging has been shown by some investigators to have similar diagnostic performance to MR arthrography for labral tear detection. Sundberg and colleagues compared acetabular labral tear detection at 3-T conventional MR with 1.5-T MR arthrography. In this study, conventional MR imaging found 4 arthroscopically confirmed labral tears also identified at MR arthrography; however, conventional MR imaging found 1 labral tear that was not visualized at MR arthrography. A limitation of this study was that only 8 patients were studied and only 5 patients underwent arthroscopic surgery. Moderate echo time fast spin-echo sequencing with an effective echo of approximately 34 ms at 1.5 T and 28 ms at 3 T is recommended for conventional MR imaging.

MR Arthrography (Direct)

MR arthrography of the hip is the preferred imaging technique for evaluating the labrum due to joint distention and anesthetic injected at the time of arthrography. The anesthetic portion of the arthrogram is key to many ordering providers because of the potential association between pain relief with anesthetic and intra-articular pathology.

The hip joint is usually injected under fluoroscopic guidance using an anterior/anterolateral approach. The standard dilution of gadolinium for joint distention is 0.2 mmol/L to optimize the paramagnetic effect. There are several ways to obtain this concentration, depending on whether iodinated contrast material is mixed with the gadolinium. This mixture is injected until the joint is distended (approximately 12–15 mL), stopping if the patient feels an uncomfortable fullness or a higher pressure impedes injection. Intra-articular administration of anesthetic within this solution is considered standard to determine any relief of pain with intra-articular anesthetic. The authors’ injectate consists of 0.1 mL gadolinium, 5 mL iodinated contrast, 5 mL normal saline, 5 mL 0.5% ropivacaine, and 5 mL 1% lidocaine. Patient pain level should be recorded immediately and 2 to 4 hours after injection, and patients should perform activities after the injection that typically produce their pain to determine if there is improvement in pain symptoms.

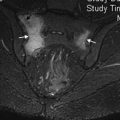

Imaging should be performed using a surface coil. Because of the spherical nature of the acetabulum, it is important to use at least 3 imaging planes to ensure that all portions of the labrum are assessed. Imaging parameters include a small field of view (14 cm to 16 cm), at least a 256 to 320 × 224 to 256 matrix (512 × 512 matrix, if possible), and section thickness of 3 mm to 4 mm. T1-weighted fast spin-echo with fat-suppression images are obtained in at least 3 imaging planes ( Fig. 1 ). The authors obtain T1 fat-suppressed images in the standard coronal, sagittal, and axial oblique planes. A fluid-sensitive sequence, either T2 fat-suppressed or short tau inversion recovery (STIR), should be obtained to assess bone marrow edema or other soft tissue or muscle abnormalities around the hip. The authors perform a coronal T2-weighted sequence. A non–fat-suppressed T1-weighted sequence to assess bone marrow and muscles should be included; the authors obtain axial T1 and have added a sagittal intermediate-weighted sequence for additional assessment of the labrum, cartilage, and hip abductor tendons. Radial imaging may be used for the assessment of labral pathology. Yoon and colleagues, however, found that radial imaging did not reveal any additional labral tears at MR arthrography; however, the morphologic assessment for femoroacetabular impingement changes may be better detected with radial imaging. Some investigators advocate large field-of-view STIR coronal images that include the entire symphysis pubis and the sacrum.

MR arthrography has high diagnostic performance for the detection of labral tears with accuracies greater than 90%. Ziegert and colleagues found the axial oblique plane to have the highest detection rate of arthroscopically proved acetabular labral tears and more than 95% of tears were identified with the use of 3 imaging planes. A recent meta-analysis of the literature comparing the diagnostic accuracy of acetabular labral tear detection, using conventional MR imaging and MR arthrography, concluded conventional MR imaging and MR arthrography are both useful imaging techniques in diagnosing labral tears in the adult population. MR arthrography seems, however, superior to conventional MR imaging with higher sensitivity with MR arthrography.

MR Arthrography (Indirect)

There are few data on the diagnostic performance of indirect MR arthrography in the detection of acetabular labral tears. The impetus to use indirect MR arthrography is that it is considered by some investigators less invasive than the direct technique and does not require fluoroscopy or a physician to perform the injection and allows visualization of synovitis and extra-articular enhancement. A main disadvantage compared with direct MR arthrography, however, is the lack of capsular distention. Timing of the scan after intravenous injection also may be problematic. A recent study by Zlatkin and colleagues found 100% of labral tears at indirect MR arthrography (13 labral tears at arthroscopy), whereas 85% were detected by conventional MR imaging. They did not compare the diagnostic performance in this patient population with direct MR arthrography. They conclude that indirect MR arthrography may be a viable alternative to direct MR arthrography when appropriate. It is these investigators’ belief, however, that indirect MR arthrography of the hip is not yet ready for prime time.

CT Arthrography

CT arthrography of the hip may be a useful technique in patients with adjacent metal hardware or in those who are unable to complete the MR examination due to claustrophobia. CT arthrography with radial reformation was found to have a high sensitivity (97%), specificity (87%), and accuracy (92%) in labral tear detection in patients with hip dysplasia and has been shown to accurately define articular cartilage defects. In the study by Perdikakis and colleagues comparing MR arthrography with multidetector CT arthrography, MR arthrography was found better for the detection of labral tears. The scan parameters should include thin slice thickness (0.5–1.25 mm), small field of view (16 cm), 120 to 140 kV(p), and 140 to 300 mAs. Isotropic data acquisition allows multiplanar reformation with 1-mm section thickness in the sagittal, coronal, and axial oblique planes.

Sonography

As with most joints, the role of sonography in the hip is probably best limited to evaluation of 1 or 2 specific questions. For instance, this is a fine technique for evaluating pathology of individual tendons but should not be routinely used to survey the entire hip joint. Sonography can pinpoint suspected bursitis and can demonstrate snapping tendons. It is ideal for performing imaging-guided injections. The acetabular labrum can be visualized at the anterior attachment onto the acetabulum with sonography. The normal fibrocartilage labrum appears hyperechoic and triangle-shaped, whereas a labral tear appears as a hypoechoic cleft ( Fig. 2 ). The longitudinal plane allows the best assessment of the anterior labrum. The role of sonography in diagnosis of labral pathology is limited given the incomplete evaluation of the entire labrum and low diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity (44%–82%) compared with MR arthrography. A paralabral cyst appears as a hypoechoic multilocular fluid collection adjacent to the acetabular labrum and may aid in the diagnosis of labral tear.

Normal imaging anatomy

Understanding the MR imaging appearance of the normal labrum is important for accurate MR assessment of the labrum. The labrum is generally triangular in cross-section because it arises from the rim of the acetabulum (see Fig. 1 ), although it can have a variable shape at MR imaging. These labral shapes include triangular (most common), round, flat, or absent. A previous study by Abe and colleagues showed a triangular labral shape in 96% of patients who are 10 to 19 years old but in only 62% of patients older than 50 years of age. They proposed that the loss of the normal triangular-shaped labrum may be due to degeneration. There is controversy whether an absent labrum is congenital or secondary to degeneration. In middle-aged or elderly patients, an absent labrum is likely due to labral tearing or degeneration. The labrum is thinner anteriorly and thicker posteriorly. The labrum is diffusely low signal intensity on all pulse sequences due to the fibrocartilage composition. Intermediate or high signal intensity can be present within the acetabular labrum as seen in asymptomatic individuals. This intermediate to high signal intensity may be due to mucoid degeneration, presence of intralabral fibrovascular bundles, or may be due to magic angle. This labral signal may mimic a labral tear on conventional MR imaging.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree