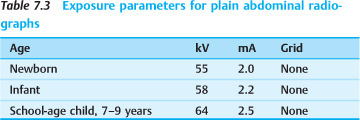

Acute Abdomen in the Pediatric Intensive Care Patient 7 Gastrointestinal Atresia and Stenosis Congenital Megacolon (Hirschsprung Disease) The differential diagnosis of diseases that present with an “acute abdomen” in children is very broad and varies with the age of the patient (Table 7.1). Acute abdominal pain is one of the most frequent indications for radio-graphic examinations in children. Diseases of the gastrointestinal tract are the leading cause, but extra-abdominal diseases such as basal pneumonia may also underlie an acute abdomen. Moreover, it is sometimes difficult in children to distinguish somatic pain from pain due to a psychosocial conflict. The limited ability of these young patients to cooperate and communicate makes it difficult to take an accurate history and conduct a radiologic evaluation. This chapter deals with the differential diagnosis and imaging of an acute abdomen that may occur in pediatric intensive care patients, may prompt admission to an intensive care unit, or may require evaluation by a radiologist in an acute emergency. Abdominal emergencies in school-age children show a broad overlap with diseases and findings in adults, and so the discussions in this chapter will be limited to diseases in neonates and small children. Ultrasonography is the primary imaging modality for evaluating an acute abdomen in children, even after trauma. Ultrasound scans have replaced plain abdominal radiographs and contrast examinations in many cases. A basic rule is the smaller the patient, the higher the operating frequency of the ultrasound transducer (Table 7.2). Upright abdominal radiographs are poorly tolerated by most small children and tend to be of poorer quality than comparable supine radiographs. On the whole, however, plain films of an acute abdomen are nonspecific and may contribute little to making a diagnosis. Given these limitations, strict criteria should be applied in selecting children for plain abdominal radiographs (Table 7.3).

M. Hoermann

Examination Technique

Ultrasonography

Plain Abdominal Radiograph

Neonates | Infants and small children | School-age children |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age | GI tract | Parenchymal organs |

Newborn | 12–15 MHz | 10–12 MHz |

Small child | 12–15 MHz | 7 MHz |

School-age child | 10–12 MHz | 5–7 MHz |

Coverage should always include the basal lung zones and inguinal region so that basal pneumonia or an incarcerated hernia can be recognized. If free air is suspected, a chest radiograph should be obtained in the upright or cross-table supine position (see Figs. 7.5b and 7.6b).

Oral Contrast Examinations

Contrast examinations of the gastrointestinal tract are rarely necessary. The contrast medium may consist of barium or a nonionic water-soluble material.

Gastrografin should not be used in children, as its hyperosmolarity may lead to life-threatening dehydration and cause toxic injury to the gastrointestinal mucosa in neonates.

Meconium Ileus

Meconium ileus is the initial manifestation of cystic fibrosis in ca. 15% of affected newborns. The inspissation of bowel contents due to abnormal intestinal secretions prevents the normal passage of meconium.

Imaging

The plain abdominal radiograph shows signs of a low obstruction as in atresia or stenosis but without significant prestenotic dilatation. Air–fluid levels are very rarely seen owing to the inspissated condition of the meconium. The viscous meconium sometimes contains small air bubbles. This may suggest the correct diagnosis but is nonspecific, as it may also result from a distal obstruction due to other causes.

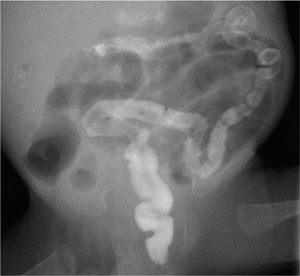

The contrast enema is both therapeutic and diagnostic and demonstrates a poorly distensible microcolon (“unused colon,” Fig. 7.1). When contrast medium enters the terminal ileum, the radiograph shows irregular filling defects caused by inspissated meconium.

Therapeutic contrast enema with a hypertonic medium is successful in up to 60% of cases. Attention must be given to avoiding perforations (up to 5% of cases) and to the maintenance of fluid balance.

Complications

Calcifications in the abdominal radiograph suggest an intrauterine perforation, possibly associated with pseudocyst formation, as a possible complication of meconium ileus. Other potential complications are volvulus and atresia.

Fig. 7.1 Meconium ileus with a nondistensible “microcolon” and dilatation of the small bowel.

Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) occurs in immature newborns (> 90% of NEC patients are delivered before 35 weeks’ gestation) several days after the start of enteral feeding; symptoms never appear before feeding is initiated. Very rarely, NEC may also occur in mature newborns. The etiology is uncertain, but NEC has a multifactorial pathogenesis based on damage to the mucosal barrier.

Sites of predilection for NEC are the terminal ileum and ascending colon, although radiographic changes are often first noted in the sigmoid colon.

Diagnostic Strategy

NEC is a clinical diagnosis. The primary imaging modality is plain abdominal radiography.

Ultrasonography is being used increasingly in the diagnosis of NEC. It can detect air in the portal veins (pneumoportogram) earlier than radiography. Ultrasound scanning can also detect a (small) pneumoperitoneum more easily and with greater sensitivity (indication for surgery!).

Imaging

The imaging findings of NEC lag well behind its clinical manifestations. Almost invariably, the child has already been placed on antibiotics by the time of radiologic evaluation and the appearance of initial x-ray signs.

Radiography

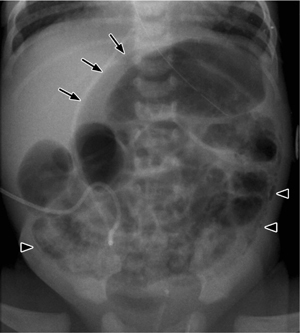

The plain abdominal radiograph shows separated and distended bowel loops (bowel wall edema). All morphologic imaging findings are nonspecific, however, and there are no specific radiographic criteria for NEC.

Pneumatosis. Pneumatosis of the bowel wall is strongly suggestive of NEC but is not specific and may be found in other inflammatory bowel diseases. For example, it may occur in the setting of a rotavirus infection, which is the most frequent cause of enteritis in infants.

Subsequent air migration through the mesenteric veins leads to a pneumoportogram (in about 10% of cases), which does not correlate with the severity of the disease (Fig. 7.2).

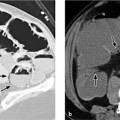

Perforation. NEC is responsible for more than 50% of pediatric abdominal perforations. Pneumoperitoneum is an indication for surgical treatment (Fig. 7.3).

The supine abdominal radiograph will show the following signs of “free air” in cases where perforation has occurred (Table 7.4):

Air bordering the falciform ligament on both sides

Air bordering the falciform ligament on both sides

Continuity of the diaphragm shadow across the midline (unlike pneumothorax, which is confined to one side) (Fig. 7.4)

Continuity of the diaphragm shadow across the midline (unlike pneumothorax, which is confined to one side) (Fig. 7.4)

Intramural and extramural air marking both sides of the bowel wall (Rigler sign, Fig. 7.5b)

Intramural and extramural air marking both sides of the bowel wall (Rigler sign, Fig. 7.5b)

Triangular air collections between the bowel loops (triangle sign, Fig. 7.5)

Triangular air collections between the bowel loops (triangle sign, Fig. 7.5)

Rounded midabdominal lucency (football sign) on the supine radiograph caused by anterior migration of large amounts of free air (Fig. 7.6)

Rounded midabdominal lucency (football sign) on the supine radiograph caused by anterior migration of large amounts of free air (Fig. 7.6)

Fig. 7.2 Necrotizing enterocolitis with pneumatosis of the colon wall (arrowheads) and a rounded collection of free air (football sign) due to a perforation (arrows).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Atresia and stenosis

Atresia and stenosis Pyloric hypertrophy

Pyloric hypertrophy Appendicitis

Appendicitis Meconium ileus

Meconium ileus Intussusception

Intussusception Diseases of adnexa

Diseases of adnexa Malrotation and volvulus

Malrotation and volvulus Duplications

Duplications Urologic diseases

Urologic diseases Necrotizing enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis Foreign-body ingestion

Foreign-body ingestion Blunt abdominal trauma

Blunt abdominal trauma Hirschsprung disease

Hirschsprung disease Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis Cholecystitis

Cholecystitis Biliary diseases

Biliary diseases Mesenteric lymphadenitis

Mesenteric lymphadenitis Pancreatitis (in the setting of biliary tract anomalies)

Pancreatitis (in the setting of biliary tract anomalies) Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis Febrile urinary tract infection

Febrile urinary tract infection Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis Tumors

Tumors Meckel diverticulum

Meckel diverticulum

Gastrografin should not be used in children, owing to the risk of dehydration and its toxicity to gastrointestinal mucosa in newborns.

Gastrografin should not be used in children, owing to the risk of dehydration and its toxicity to gastrointestinal mucosa in newborns.