ACUTE AND SUBACUTE FUNGAL SINUSITIS

KEY POINTS

- Imaging should be used early in patients who are suspected of harboring invasive fungal rhinosinusitis.

- There is a reasonable set of imaging guidelines presented in this chapter that can help assess risk and need for referral for examination beyond simple anterior rhinoscopy.

- Imaging together with sophisticated clinical evaluation can identify early disease before it requires very morbid surgery as part of the treatment plan.

- Imaging is critical in identifying and excluding orbital and intracranial complications of invasive fungal, although it can never exclude meningitis.

INTRODUCTION

Etiology

Rhinosinusitis may be classified by the infecting organism as viral, bacterial, or fungal.1 Fungal involvement is most commonly a noninvasive colonization or saprophytic type of host organism relationship. This noninvasive form is a common finding in chronic sinusitis often caused by allergy that is discussed in Chapter 85.

Aggressive fungal infection, which may be minimally to moderately invasive or fulminate, is discussed in this chapter separate from other etiologies of rhinosinusitis because of its typically disparate clinical settings. The pathophysiology and spread patterns of invasive fungal infection also differ from those of the more common viral and bacterial infections that cause rhinosinusitis.

Recognition of early acute fungal sinusitis requires a high index of suspicion. This chapter attempts to set forth the pivotal role of computed tomography (CT) in identifying patients at significant risk for invasive fungal rhinosinusitis given a reasonable clinical context. An approach developed over almost 30 years for this risk assessment is presented in the following Pathophysiology and Patterns of Disease section.2,3

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Fungal infections of the paranasal sinuses are uncommon. Acute and subacute invasive fungal sinusitis occurs almost exclusively in immune-compromised patients, diabetic patients, and the “frail” elderly. Other patients at risk are those using steroids or receiving broad spectrum antibiotics.

Aspergillosis, mucormycosis, candidiasis, histoplasmosis, and coccidiomycosis are the more commonly occurring forms. Aspergillosis is the most common offending pathogen.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with acute and subacute rhinosinusitis of any etiology will have rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, facial pressure and pain, diminished sense of smell, and perhaps fever. The initial signs of invasive fungal infection include engorgement of the turbinates and nasal obstruction, followed by ischemia and thrombosis leading to necrosis of the turbinates and a bloody discharge. The area of involvement may appear black. Orbital and visual symptoms occasionally dominate the presentation.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Anatomy

The nasal cavity and sinus anatomy is discussed in detail in Chapter 78. In particular, the anatomy of the major neurovascular bundles of this region should be reviewed, including the distal maxillary artery in the pterygopalatine fossa, the posterior superior alveolar group that spreads out over the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus, the infraorbital including its distal course beyond the infraorbital canal deep to the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS), and the anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries.

Pathophysiology and Patterns of Disease

The basic mechanisms of disease spread and related morphologic changes in invasive fungal disease are discussed and illustrated in Chapters 13, 15, and 16. These infections are usually due to aspergillosis or mucormycosis and occur mainly in patients who are immune compromised or diabetic. Ketoacidosis predisposes to mucormycosis because the acidic, glucose-rich environment favors fungal growth. The “frail” elderly without other identifiable underlying disease and those on steroids or chronic antibiotic therapy are a less frequent target population (Figs. 86.1 and 86.2). This aggressive or fulminate fungal disease tends to be angioinvasive, in particular arterial invasive (Figs. 13.6, 15.10, 15.11, 16.2, 16.9, and 86.1–86.7 and Chapters 13, 15, and 16); thus, diffuse inflammation may be accompanied by soft tissue and bone necrosis (Figs. 86.8–86.12).

A hallmark of the disease is its predictable involvement of vascular bundles. In rhinosinusitis, the vascular pedicles and their ramifications at risk are those passing out of the sphenopalatine foramen into the posterior nasal cavity (Figs. 15.10, 15.11, 16.9, and 86.1–86.4 and Chapters 15 and 16), those traveling in the infraorbital canal, and the posterior superior alveolar vessels (Figs. 13.6, 15.11, 16.12, and 86.3–86.7) that penetrate the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus. These vascular pathways allow disease to be on both sides of adjacent bone, sometimes without frankly destroying bone3 (Figs. 15.10, 15.11, 16.9, 86.5, and 86.7 and Chapters 15 and 16). The disease can then be recognized by perivascular infiltration of the fat bordering these bony channels as the vessels pass through surrounding fat pads en route to or from their respective foramina and canals.3 Regions important in the search for early imaging findings of invasive fungal rhinosinusitis include the fat pad of the canine fossa deep to the SMAS, extraconal fat along the orbital floor, the retroantral (retromaxillary) fat pad of the infratemporal fossa, and the fat of the pterygopalatine fossa.

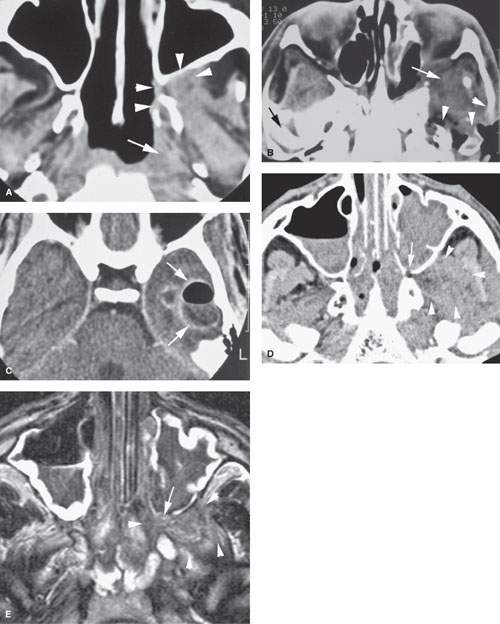

FIGURE 86.1. Two patients with mucormycosis. A–C: Patient 1 is an elderly diabetic patient with diabetes believed to be under reasonable control. In (A), the non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) study shows a discreet infiltrating mass in the pterygopalatine fossa and retroantral fat (arrowheads) with erosion of the pterygoid plate. There is also a discreet infiltrating nasopharyngeal mass (arrow). In (B), a section somewhat more superior than that seen in (A) and done at a later time because of worsening symptoms. There is an infiltrating mass extending from the inferior orbital fissure into the masticator space and eroding surrounding bony structures (arrowheads). In (C), contrast-enhanced CT shows a secondary complicating bacterial brain abscess. (NOTE: In [A], the disease appeared to be under control and the infiltrating process relatively discreet. However, this area became secondarily infected with bacteria, and the patient subsequently succumbed to intracranial abscess.) D, E: Patient 2 is a diabetic with poorly controlled disease. In (D), the non–contrast-enhanced CT study shows extensive disease in the sinus and nasal cavity eroding the bone around the pterygopalatine fissure (arrow) and widely infiltrating the masticator space (arrowheads). In (E), the T2-weighted image shows the extensive chronic polypoid mucosal thickening in the sinuses and nasal cavity with the invasive fungal disease growing through the posterior maxillary sinus wall into the pterygopalatine fossa (arrow) and then into the infratemporal fossa (arrowheads). Note that the disease is darker in signal intensity than most infiltrating neoplastic and inflammatory processes—a signal characteristic of invasive fungal sinus disease although not entirely specific.

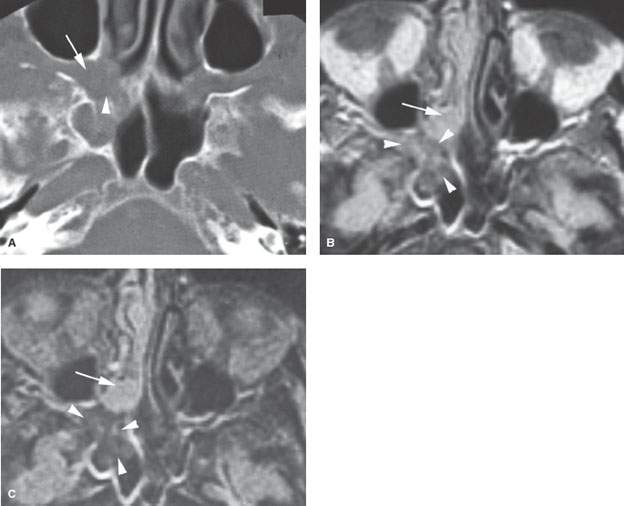

FIGURE 86.2. An immune-compromised patient due to lymphoma. The patient had retro-orbital pain and nasal congestion. A: Computed tomography study at bone windows showing an infiltrating mass extending from the sphenopalatine foramen into the pterygopalatine fossa (arrow) and destroying bone along the face of the sphenoid sinus (arrowhead). B, C: Contrast-enhanced T1- and T2-weighted images, respectively, showing the difference in signal intensity between inflammatory changes and swelling in the nasal cavity involving the turbinates (arrows) and the process that was invasive more posteriorly (arrowheads). Differential diagnostic considerations were recurrent lymphoma or invasive aspergillosis. Fungal infection was proven. (NOTE: While the tissue of invasive fungal sinus disease does appear generally darker than the usual inflammatory tissue as seen on magnetic resonance imaging, that signal tendency does not differentiate this process from infiltrating neoplasms such as lymphoma and tissue sampling is required.)

One of the hallmarks of such invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is also frank bone erosion (Figs. 86.3, 86.8, 86.10, and 86.12A), but the invasive soft tissue patterns without obvious bone invasion must be kept in mind when trying to diagnosis invasive fungal disease as early as possible. These findings can be used in evaluating CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies to triage patients at significant risk to those requiring definitive nasal endoscopy and possible tissue sampling, based on 25 years of mainly unpublished3 experience at the University of Florida as follows:

Low Risk

- Scattered, bilateral sinus mucosal thickening of any degree without perivascular spread or bone erosion

- Localized sinus mucosal thickening without perivascular spread or bone erosion

Moderate Risk

- Unilateral posterior nasal cavity disease projecting toward the sphenopalatine foramen without perivascular spread or bone erosion (Fig. 86.8)

- Unilateral middle meatus and adjacent sinus disease without perivascular spread or bone erosion

High Risk

- Mucosal disease at any site that shows bone erosion or soft tissue necrosis (Fig. 86.9)

- Mucosal disease associated with loss of fat planes in the canine fossa deep to the SMAS, along the extraconal fat surrounding the infraorbital vascular bundle, along the retromaxillary fat pad, at the orbital apex or in the superior and inferior orbital fissure, and/or within the pterygopalatine fossa (Figs. 86.1–86.7)

- An infiltrating process in the nasopharynx (Figs. 86.5 and 86.9)

Low-risk patients are followed clinically and may be treated as viral or bacterial infections or sometimes graft versus host reactions, and an otolaryngology consult may not be obtained. Moderate-risk patients receive nasal endoscopy by the otolaryngology service and tissue sampling if appropriate; these patients may be followed with CT if symptoms persist or progress even in the absence of endoscopic confirmation of fungal infection. High-risk patients receive nasal endoscopy and tissue sampling by the otolaryngology service at the site most likely to yield definitive tissue.

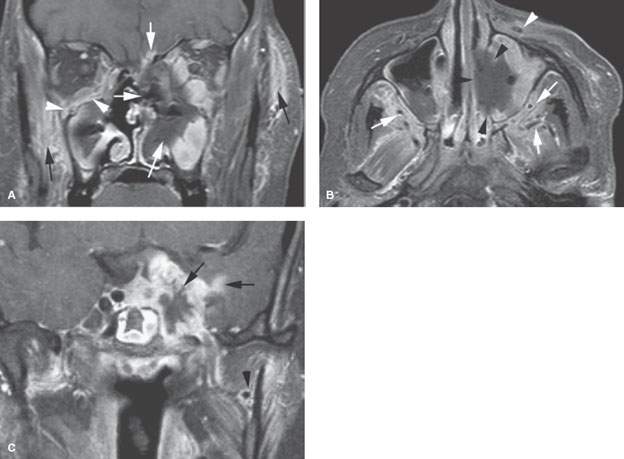

FIGURE 86.3. The patients in this figure and in Figure 86.4 illustrate the general range of findings from advanced to relatively early fungal sinus disease as seen on magnetic resonance imaging. A–C: An immune-compromised patient with advanced disease. In (A), the contrast-enhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted (T1W) image shows the invasive necrotic tissue in the left nasal cavity invading the orbit, through the anterior skull base (white arrows), and into surrounding soft tissues (black arrows). On the right side, more discreet subperiosteal spread of disease is seen along the floor of the orbit (arrowheads). In (B), the contrast-enhanced T1W fat-suppressed image in the axial plane shows the tendency of advanced disease to be grossly necrotic (black arrowheads) and to spread along arterial branches of the distal maxillary vessels (white arrows) within the infratemporal fossa and along the infraorbital neurovascular bundle (white arrowhead) on the left. Fungal disease tends to be angioinvasive principally along arteries. In (C), the T1W fat-suppressed image shows that fungal disease will spread intracranially, usually along vessels. In this case, it is grossly invading the cavernous sinus likely by perivascular spread with extension into the brain, again likely along the vessels of the pia-arachnoid (arrows). This coronal view also shows the periarterial spread along the maxillary artery (arrowhead).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree