Epidemiology

Acute appendicitis is a common clinical concern in patients presenting to the emergency department with abdominal pain, with a lifetime risk of 5% to 7%. The mortality rate is less than 1% but may be as high as 20% in certain populations, such as the elderly. In the clinical evaluation and diagnostic investigation of patients with acute right lower quadrant pain, other conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis. These include right-sided diverticulitis, acute cholecystitis, epiploic appendagitis, renal or ureteral stones, omental infarction, bowel obstruction, and, in females, acute gynecologic conditions.

Epidemiology

Acute appendicitis is a common clinical concern in patients presenting to the emergency department with abdominal pain, with a lifetime risk of 5% to 7%. The mortality rate is less than 1% but may be as high as 20% in certain populations, such as the elderly. In the clinical evaluation and diagnostic investigation of patients with acute right lower quadrant pain, other conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis. These include right-sided diverticulitis, acute cholecystitis, epiploic appendagitis, renal or ureteral stones, omental infarction, bowel obstruction, and, in females, acute gynecologic conditions.

Pathology

Initially, the appendiceal lumen occludes secondary to a number of causes, including fecaliths and lymphoid hyperplasia. Once it is occluded, intraluminal fluid continues to accumulate, distending the appendix and eventually increasing the intraluminal and intramural pressures to the point of vascular and lymphatic obstruction. Ineffective venous and lymphatic drainage allows bacterial invasion of the appendiceal wall and lumen. If this bacterial infection is not treated, perforation of the appendix and peritonitis may ensue.

Imaging

Radiography

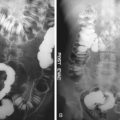

Abdominal radiographs have very limited clinical utility in patients with suspected appendicitis. A calcified fecalith (appendicolith) may be identified in the right lower quadrant ( Figure 15-1 ), or there may be a focally dilated loop of small bowel (“sentinel loop” sign).

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) is the preferred method for diagnosing appendicitis, either after a nonconclusive ultrasound examination or as the first imaging test. On CT, the appendix appears enlarged, often with surrounding inflammatory changes, fascial thickening, and small amounts of free intraperitoneal fluid ( Figures 15-2 and 15-3 ). Appendicoliths are also readily identified on CT ( Figure 15-4 ). There may be edema at the origin of the appendix, as evidenced by thickening of the adjacent cecum, the “arrowhead” sign. There is a wide variation in the diameter of the appendix in normal patients, with sizes ranging up to 1 cm. However, mean values range between 5 and 7 mm. Therefore, when the appendix measures slightly greater than the standard cutoff value of 6 mm, secondary signs of inflammation should be sought to determine if appendicitis is present. Filling of the appendix by orally or rectally introduced positive contrast material is a useful imaging finding in excluding obstruction of the appendix and, therefore, acute appendicitis. However, isolated involvement of the distal segment of the appendix (“tip” appendicitis) is seen occasionally. In patients in whom the appendix is not visualized, this finding, in the absence of right lower quadrant inflammation, carries a high negative predictive value of appendicitis.

The most important complication of acute appendicitis that should be recognized with CT is focal appendiceal rupture. Signs of rupture include periappendiceal abscess ( Figure 15-5 ), extraluminal gas (localized or free), free peritoneal fluid, and focal poor enhancement of the appendiceal wall. Other, less common complications include diffuse peritonitis (with free gas in the peritoneal cavity) and portal vein thrombosis.