Etiology

The causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding include esophageal or gastric varices, Mallory-Weiss tears, gastritis, and gastric or duodenal ulcers. Common causes of lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding include colonic diverticulosis, ischemic and infectious colitis, colonic neoplasm, benign anorectal disease, arteriovenous malformations, ischemia, and Meckel’s diverticulum.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Acute gastrointestinal bleeding is classified into upper and lower gastrointestinal regions based on the site of hemorrhage (proximal or distal to the ligament of Treitz). Acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage is a common cause of hospital admission, with significant associated morbidity and mortality. Rapid stabilization of and therapy for patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding is critical. The mortality rate is reported to be up to 20% in cases of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage, depending on the cause. Mortality in patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding is reported to approach 20%.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Acute gastrointestinal bleeding is classified into upper and lower gastrointestinal regions based on the site of hemorrhage (proximal or distal to the ligament of Treitz). Acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage is a common cause of hospital admission, with significant associated morbidity and mortality. Rapid stabilization of and therapy for patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding is critical. The mortality rate is reported to be up to 20% in cases of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage, depending on the cause. Mortality in patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding is reported to approach 20%.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage typically present clinically with hematemesis, hematochezia, or melena. Patients with acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage can report melena or hematochezia. When severe, gastrointestinal hemorrhage may result in hemodynamic instability and shock. Importantly, the amount of blood passed in vomitus or stool does not serve as a reliable indicator of the severity of the event, because large amounts of blood can be sequestered in the intestines.

In addition to the total amount of blood lost, the rate of bleeding and the overall health of the patient are other factors determining the clinical presentation and the need for emergent intervention. Healthy patients have a tremendous capacity to compensate for acute blood loss. In young individuals with no cardiovascular disease, up to 2 units of blood can be lost with minimal or no hemodynamic changes. Blood flow can be diverted from the skin, splanchnic circulation, and kidneys to maintain perfusion of essential organs such as the brain and heart. Hypotension and tachycardia indicate a larger volume of blood loss, whereas confusion and oliguria develop when bleeding loss reaches 3 to 4 units. Finally, although there is usually a rush to intervene, up to 75% or 80% of the patients will experience spontaneous cessation of bleeding before any therapy is initiated.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of gastrointestinal hemorrhage depends on the underlying cause. Peptic ulcer disease results in a defect in the gastroduodenal mucosa with eventual exposure and damage to the underlying arteries, including arteritis, aneurysmal dilatation, and eventual rupture and hemorrhage. Mallory-Weiss tears result spontaneously from the marked increase in intraluminal pressures associated with retching and are associated with the presence of a hiatal hernia. Linear tears within the mucosa of the distal esophagus, cardioesophageal junction, or cardia result in injury to the underlying vasculature with subsequent hemorrhage. In patients with varices, increasing hepatic venous pressure results in enlarged varices and the increased risk for rupture and hemorrhage.

Diverticular hemorrhage results from rupture of the vasa recta at the dome of the diverticulum. These vessels have eccentric intimal thickening with asymmetric rupture, suggesting that trauma to these vessels results in intimal proliferation and scarring, leading to subsequent rupture and hemorrhage. Angiodysplasia is typically located within the lower gastrointestinal tract, specifically the right colon. Although the pathophysiology is incompletely understood, angiodysplastic lesions are thought to be acquired degenerative lesions.

Imaging

Radiography

Abdominal radiographs have limited clinical utility in patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Abdominal radiographs have been demonstrated not to affect clinical outcomes or management decisions in patients admitted to an intensive care unit with gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Computed Tomography

Recently, computed tomography (CT) has been shown to have a high diagnostic accuracy in both the detection and the localization of massive gastrointestinal bleeding ( Figure 17-1 ). Optimal results necessitate the distention of the bowel with a contrast agent with neutral attenuation, such as water or low-density barium suspensions ( Figure 17-2 ). Both unenhanced and arterial-phase intravenous contrast-enhanced acquisitions should be acquired. CT diagnosis relies on the visualization of an area of active arterial contrast extravasation. In the majority of cases, CT may diagnose the underlying cause of acute hemorrhage, such as in the case of small bowel or colonic neoplasms. The efficiency and ease of acquisition as well as reported diagnostic accuracies of multidetector CT in the evaluation of acute gastrointestinal bleeding make this a promising first-line imaging modality.

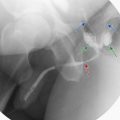

Nuclear Medicine

The use of nuclear scintigraphy is sensitive in the detection and accurate in the localization of the source of acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Both technetium-99m ( 99m Tc)–labeled red blood cells and 99m Tc sulfur colloid are applied in the evaluation of acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage. However, 99m Tc-labeled red blood cells offer the possibility for delayed imaging in cases of intermittent bleeding. The diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding on nuclear scintigraphy depends on the visualization of an area of tracer localization that persists and should be seen to move through the lumen of the bowel secondary to peristalsis. Both antegrade and retrograde transit are observed, but localization depends on the initial area of visualization ( Figure 17-3 ). The localization of the site of bleeding has been shown to be highly accurate with nuclear scintigraphy and clinically useful in guiding subsequent transcatheter therapies or surgical resection. Single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography erythrocyte scintigraphy has demonstrated superior accuracy and precision over planar scintigraphy in the diagnosis of acute gastrointestinal bleeding.