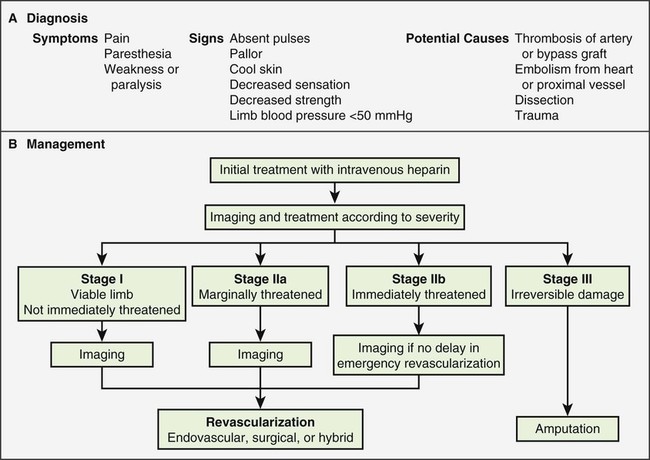

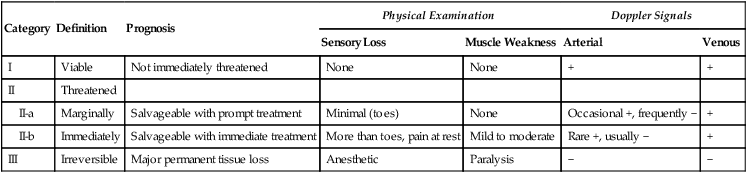

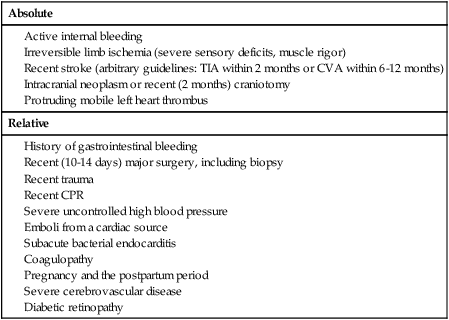

Raymond W. Liu, Hani H. Abujudeh, David W. Trost and Krishna Kandarpa An acute profoundly ischemic limb is a surgical emergency. Cell death begins within 4 hours of total ischemia and is irreversible after 6 hours. Revascularization in this setting may result in sudden tissue reperfusion and lead to a systemic acid-base disorder and impaired cardiopulmonary function.1 In the late 1970s, Blaisdell et al. documented mortality rates in excess of 25% after open surgical repair of ALEI.2 Operative mortality remains high despite advances in surgical technique and management.3 Amputation rates can vary from 10% to 30%.4 Treatment generally begins with early anticoagulation with heparin to limit propagation of the thrombus. This has traditionally been followed by surgical thromboembolectomy and correction (patch angioplasty or bypass graft) of the culprit lesion to restore arterial flow.5 Thrombolytic therapy provides an attractive alternative to open surgery because it offers several advantages. It is a less invasive procedure, since it not only dissolves the primary arterial thrombus but also helps clear the microcirculation, thereby resulting in gradual reperfusion and averting the release of anaerobic metabolites and thus helping reduce the potential for sudden reperfusion and compartment syndrome.1 In the 1970s, intravenous thrombolytic agents (e.g., streptokinase) were shown to restore patency in acutely occluded arteries in 75% of cases.6 However, systemic infusion of thrombolytic agents carries a high risk of remote bleeding complications and has largely been abandoned in favor of catheter-directed local thrombolytic therapy. Local intraarterial thrombolytic therapy has gained popularity over the past 20 years and in many cases, barring contraindications, is the initial intervention of choice. Thrombolytic agents are infused directly into the occluding thrombus in a concentrated fashion so systemic drug concentration and the total dose required for the procedure are reduced. As flow is restored, the underlying culprit lesion is usually unmasked and managed by interventional or surgical techniques. A classification system was devised by the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS, United States) and updated by The TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus (TASC) II guidelines in 2007 for describing the degree of acute limb ischemia (Table 33-1). The main objective of this categorization is to stratify the acuity of limb ischemia into defined groups for decision-making purposes. The TASC II guidelines also suggest an algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment of acute limb ischemia (Fig. 33-1).7 TABLE 33-1 Society for Vascular Surgery Clinical Categories of Acute Limb Ischemia Modified from Rutherford RB, Baker JD, Ernst C, et al. Recommended standards for reports dealing with lower extremity ischemia: revised version. J Vasc Surg 1997;26:517–38. ©The Society for Vascular Surgery and the North American Chapter of the International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery. Percutaneous intraarterial thrombolysis (PIAT) is indicated in patients who have acute-onset claudication (SVS I, the limb is generally viable) or limb-threatening ischemia (generally SVS II-a, but also SVS II-b) due to thrombotic or embolic arterial occlusion.5,8 McNamara et al. described occlusion patterns and found that all patients with a single occluded segment but normal inflow and patent collaterals (generally SVS I) successfully underwent PIAT, with no deaths or amputations.5 In patients with normal inflow and patent collaterals but tandem occluded segments, PIAT was successful in 90% and had a mortality of 0.7% and a limb loss rate of 8.2%. In patients with irreversible limb ischemia (SVS III), PIAT has unacceptably high morbidity and mortality and is therefore not indicated (see Fig. 33-1). Patients who are considered to have viable or marginally threatened limbs may have imaging performed prior to angiography and thrombolytic therapy. Available modalities include duplex ultrasonography, computed tomographic angiography (CTA), and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). Previously thrombolysis was used to clear the acute thrombosis of a popliteal aneurysm to visualize a suitable distal runoff vessel for surgical bypass when the initial diagnostic arteriogram failed to do so.9 These days, with the availability of MRA, which has high sensitivity for demonstrating these distal vessels, this practice has been abandoned for the most part. Indications for salvage of a graft require consideration of the individual case.10 There are twin goals of removing the clot and correcting the underlying lesion. If the underlying lesion is secondary to diseased inflow or outflow, progression of atherosclerotic disease is usually the primary etiology. In this scenario, treatment with angioplasty/stent or bypass grafting has demonstrated success. If the underlying lesion is secondary to intrinsic graft disease, either intimal hyperplasia or graft stenosis is usually the primary etiology. The type of conduit can guide treatment, since prosthetic grafts will develop intimal hyperplasia, while venous bypass grafts often develop stenosis at the site of a valve. Prosthetic grafts may not have successful long-term results with angioplasty and require surgical graft thrombectomy and patch angioplasty. Venous bypass grafts can be treated successfully by angioplasty and/or stenting. Relative and absolute contraindications are listed in Table 33-2. Absolute contraindications include active internal bleeding, cerebrovascular events such as a recent (within 6-12 months) cerebrovascular accident or a transient ischemic attack (within 2 months), known intracranial neoplasm, or craniotomy within 2 months. TABLE 33-2 Contraindications to Local Catheter-Directed Thrombolytic Therapy CPR, Cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; TIA, transient ischemic attack. Irreversible ischemia (SVS III) accompanied by severe sensory loss, along with the onset of muscle rigor and absent arterial and venous signals on Doppler interrogation, puts the patient at high risk for the consequences of acute reperfusion. In this setting, PIAT is associated with a high rate of amputation (25%) and mortality (13%).10 A surgical approach is advised in this clinical setting. Of note, in elderly patients with uncontrolled hypertension who were treated for acute myocardial infarction with systemic thrombolytic therapy, a significantly greater risk for intracranial hemorrhage has been reported.11 The presence of a mobile intracardiac thrombus on echocardiography is predictive of a higher risk of embolization and should therefore be considered a relative risk for lytic therapy.12 There are several devices on the market that facilitate infusion of thrombolytic therapy, but any standard catheter, 5F or under, can be used for an end-hole infusion. Multi-sidehole catheters allow for distribution of the lytic agent along the axis of the catheter once the catheter is well embedded within the thrombus. These catheters come with different effective infusion lengths (segment of distribution of the sideholes) to match the length of the thrombus, and most can be used for both slow continuous and pulsed-spray infusion. One such catheter has pressure-responsive side slits through which jets of fluid lace the thrombus during pulse spray infusion, in addition to allowing slow continuous infusion (Uni-Fuse, SpeedLyser, and Pulse-Spray Infusion Systems [AngioDynamics Inc., Queensbury, N.Y.]). An approach increasingly used is the EkoSonic Endovascular System (Ekos Corporation, Bothell, Wash.). The system consists of a multiple-sidehole catheter through which a wire is placed that emits high-frequency, low-power microsonic energy. By exposing the thrombus to an energy source while infusing a thrombolytic, the interventionalist can achieve improved efficacy in a shorter period of time.13

Acute Lower Extremity Ischemia

Indications

Category

Definition

Prognosis

Physical Examination

Doppler Signals

Sensory Loss

Muscle Weakness

Arterial

Venous

I

Viable

Not immediately threatened

None

None

+

+

II

Threatened

II-a

Marginally

Salvageable with prompt treatment

Minimal (toes)

None

Occasional +, frequently −

+

II-b

Immediately

Salvageable with immediate treatment

More than toes, pain at rest

Mild to moderate

Rare +, usually −

+

III

Irreversible

Major permanent tissue loss

Anesthetic

Paralysis

−

−

Contraindications

Absolute

Relative

Equipment

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine