ACUTE OTOMASTOIDITIS AND ITS COMPLICATIONS

KEY POINTS

- Coalescent mastoiditis is a potentially life-threatening disease that can lead to significant neurologic deficits.

- Imaging is critical to effective diagnosis and guiding therapy in patients who potentially have complicated or uncomplicated coalescent mastoiditis.

- With atypical clinical presentation of acute otomastoiditis, imaging may significantly alter the prospective diagnosis.

INTRODUCTION

Etiology

Acute otomastoiditis is usually due to an acute pyogenic bacterial infection of the mastoid air cells and most often is seen as a complication of acute suppurative otitis media. Less frequently, acute otomastoiditis is seen secondary to chronic diseases of the middle ear, including cholesteatoma. Acute otitis media and acute otomastoiditis may be self-limiting infections; with effective therapy, the inflammatory process can be arrested. Prolonged infection, however, results in mechanical compression of the bone by a swollen mucosal lining and retained secretions and creates hyperemia and localized acidosis. This leads to osteoclastic activity, decalcification, and bone resorption within the mastoid. This is the stage of coalescent mastoiditis. As the inflammatory process goes on, the osteoclastic resorption of bone proceeds in all directions and will cause regional complications. Other infections and disease processes, such as cholesteatoma and Langerhans cell histiocytosis, can sometimes mimic its presentation.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

This is a common sporadic condition much more common in younger than older children and young adults. It is relatively uncommon in older adults unless considered together with necrotizing (malignant) otitis externa, a disease that is seen in older, usually diabetic adults due to sometimes fulminate pseudomonas infection. Necrotizing otitis externa is described in Chapter 114.

Relatively few cases of acute otomastoiditis come to diagnostic imaging since most are managed medically with antibiotics. Untreated or undertreated and potentially masked, acute suppurative mastoiditis can lead to osteolytic changes in the walls of the mastoid air cells and cortex with spread beyond the tympanic cavity and mastoid; this is often referred to as coalescent mastoiditis. While relatively uncommon in this era of advanced antibiotic therapy, this can be a morbid and rarely fatal disease. It can also be seen in immune-compromised patients and as a complicating factor in patients with pre-existing abnormalities of the temporal bone, such as chronic otitis media and acquired cholesteatoma or tumor.

Clinical Presentation

The diagnosis of acute or subacute otomastoiditis is made clinically. Patients generally are acutely ill with hearing loss, fever, and ear pain. They are tender to palpation over the mastoid and periauricular region. Signs of secondary superficial cellulitis may be present.

Palpable fluctuance suggests a related subperiosteal or more superficial extension of pus beyond the mastoid bone to surrounding soft tissues. Acute mastoiditis may occur without evidence of middle ear disease if there is a mucosal block in the aditus at the antrum; however, there will most often be obvious suppurative otitis media present if the ear can be examined definitively. Incomplete antibiotic treatment may mask any or most of these observations commonly present in the untreated patient.

Severe headache, nausea, vomiting, and dysequilibrium suggest intracranial complications that may be further suggested by physical findings such as papilledema. Facial weakness strongly suggests involvement of the facial nerve. These findings warrant emergent contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) and/or contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (CEMR).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Anatomy

A thorough knowledge of the following normal anatomy and its normal variations is essential in evaluating this disease state. This is presented in detail in Chapter 104 and summarized here.

For the primary site of disease origin:

- Middle ear, including the ossicles and tympanic membrane; mastoid, especially the sigmoid plate; Koerner septum

For threat of early spread beyond the mastoid and middle ear:

- Sigmoid plate, roof of the middle ear, mastoid labyrinthine air cell tracts

For intracranial spread and related complications:

- Sigmoid sinus, jugular bulb, petrosal sinuses, other major dural venous sinuses, vein of Labbé, and inferior surface of the temporal lobe

For facial nerve complications:

- Entire course of the facial nerve through the temporal bone and proximal extracranial course at least within the parotid gland

For spread into surrounding soft tissues:

- Outer cortex of the mastoid, sternocleidomastoid and digastric muscle attachments to the mastoid, and digastric groove

For spread to the inner ear:

- Round window, oval window, cochlea, and semicircular canals

Pathology and Patterns of Disease

The diagnosis of acute otomastoiditis is made clinically. By the time it comes to imaging, it may be in its coalescent state with the thin trabecular bone of the mastoid air cells and cortex appearing indistinct, either increased in density due to necrotic bone or frankly eroded. Similar thin bone separates the middle ear and mastoid from the middle cranial fossa, sigmoid sinus, and facial nerve. Suppuration may also spread through the oval or round window to the membranous labyrinth. Acute mastoiditis may also occur without evidence of middle ear disease if there is a mucosal block in the aditus ad antrum.

The pyogenic material in the mastoid and middle ear is under pressure and may spread directly through the areas of inherent bony weakness just described and/or within veins, resulting in serious and potentially life-threatening complications. This sometimes predominantly thrombophlebitic spread pattern can lead to epidural and subdural abscess/empyema. Bland or infected venous thrombosis can involve most or all of the major dural sinuses; most typically, it is restricted to the ipsilateral sigmoid and transverse sinuses and jugular bulb. Jugular thrombophlebitis can continue well into the neck below the skull base. Infectious major arterial complications are rare.

Venous disease can propagate into cortical veins and produce bland and/or infected cerebellar abscess and the particularly devastating infarct in the distribution of the vein of Labbé. Frank brain abscess may also occur as well as secondary leptomeningitis. Other routes of intracranial spread include a membranous labyrinthitis traveling via the cochlear duct and through pre-existing surgical defects.

Less devastating but important spread through the mastoid to surrounding extracranial soft tissues can occur in the form of cellulitis and/or abscess.

Pathologically Altered Function

The primary middle ear and mastoid infection can cause conductive hearing loss. Labyrinthitis can lead to sensorineural hearing loss and vestibular symptoms. Facial weakness is possible and nerve function can be completely and not reversibly interrupted due to acute otomastoiditis.

Intracranial spread directly or within veins can lead to neurologic deficits due to cerebellar or temporal lobe dysfunction. Meningitis and extensive major dural sinus thrombosis can lead to more generalized neurologic problems such as altered mental status and coma as well as secondary to generalized brain swelling and hydrocephalus. Cranial nerve deficits other than those related to cranial nerves VII and VIII are rare.

IMAGING TECHNIQUES

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

CECT, computed tomographic angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) studies can be very useful for the assessment of acute otomastoiditis. Frequently, CECT with CTA alone will suffice, but supplemental magnetic resonance (MR) is useful in selected cases. Non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography (NCCT) can be also used in selected “low-risk” screening situations.

CECT should be done in a balanced arterial–venous phase to allow for the detection of both venous and arterial complications as well as for the assessment of both intracranial and extracranial collections of infectious material.

MR studies should include both magnetic resonance venography (MRV) and MRA. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) can be added for the assessment of potential areas of both intra- and extracranial abscess. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted fat-suppressed images or a combination of pre- and postcontrast standard T1-weighted images may be used.

Specific protocols for this indication appear in Appendixes A and B.

Pros and Cons

Indications for Study

Site of Disease Origin

In patients with signs and symptoms suggesting acute otomastoid inflammatory disease, the site of disease origin must first be determined. The pathology responsible for the presenting signs and symptoms could be part of a more generalized process such as skull base osteomyelitis. It may also be the result of more localized disease of neighboring regions such as petrous apicitis or disease primarily of the epidural space or even that arising in surrounding soft tissue structures such as the parotid gland, temporomandibular joint, or parapharyngeal space. NCCT or CECT may be used for this initial imaging triage. If initial NCCT suggests an origin elsewhere than the middle ear or mastoid, it can also suggest whether CECT or CEMR is the next best course of action. Occasionally, noninfectious disease mimics the presentation of acute otomastoiditis, and initial diagnostic imaging will suggest an alternative etiology.

Coalescent Versus Noncoalescent Mastoiditis

Once the site of origin in the middle ear and mastoid is established, initial imaging may differentiate acute coalescent mastoiditis from acute noncoalescent mastoiditis. The latter is a common disease that almost always is treated successfully without surgery. Coalescent mastoiditis, even when uncomplicated, will usually be drained. Sometimes, such imaging triage is done in situations where the risk of acute mastoiditis is relatively low and the complaint is only mastoid pain. However, when clinical findings suggest a facial nerve complication or possible intracranial complications are suspected clinically, very urgent or emergent imaging is indicated. When the risk is low, the screening study may simply be NCCT since the diagnosis of early coalescent mastoiditis depends solely on bony findings. If there are compelling clinical reasons to give contrast, such as likely soft tissue abscess or a strong suspicion of a significant facial nerve or intracranial complication, then CECT should be used initially. MRI should not be used for such initial imaging triage because it may miss early bone changes that are so critical to diagnosis and it lacks the spatial resolution of computed tomography (CT). A case can be made for doing all initial imaging triage with CECT in a population properly screened by the referring physicians.

Extent of Disease and Related Complications

Once the site of disease origin in the mastoid and middle ear has been established, the status of the ossicles and relationship of pathology to the facial nerve, bony and membranous labyrinth, and petrous apex will be of primary interest. CECT and CEMR may be used for this purpose. It is usually best to begin with CECT while saving MRI for the cases where a more complete assessment of intracranial or otomastoid disease is necessary.

It is useful at the outset to determine whether there is associated causative pathology such as a nasopharyngeal mass obstructing the eustachian tube so that this possibility is not overlooked. It is also useful to decide if the pathology appears locally advanced or relatively contained; this distinction is usually made on the basis of the pattern of bone destruction, associated findings, and pattern of involvement of surrounding soft tissues.

The remaining analysis depends mainly on assessing the complications that might arise from infectious disease spreading beyond the temporal bone. The following specific factors should be noted in any assessment of acute otomastoiditis:

- Local extent within the middle ear, mastoid, and/or petrous apex

- Relationship to the facial nerve

- Presence of subperiosteal or other soft tissue abscess

- Direct or thrombophlebitic spread of disease to cause meningitis, epidural empyema, subdural empyema, brain abscess, or otitic hydrocephalus

- Jugular vein and/or major dural sinus thrombosis with associated brain edema and possibly venous infarction

- Spread to the inner ear causing labyrinthitis

- Carotid endarteritis and secondary thrombosis, dissection, or aneurysm

- Presence of causative pathology

Assessing Response to a Therapeutic Trial of Antibiotics

Imaging may also be used to assess the response of early coalescent disease to medical management. Surgery can then follow in cases where the infection is not responding appropriately to medical management after 72 hours.

MANIFESTATIONS OF DISEASE

Bone Erosion

Plain Film and Fluoroscopy

Plain films are a wasted step in this often critical clinical assessment and should not be done since they are insensitive to early bone erosion.

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

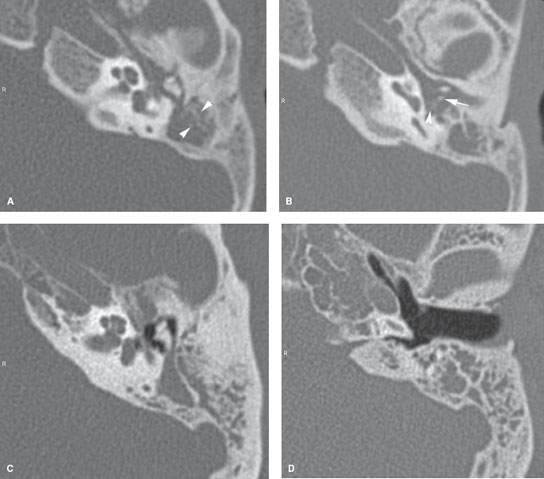

The diagnosis of acute mastoiditis (Fig. 110.1) is suspected and confirmed clinically. However, bone erosion is the critical finding for the initial and early diagnosis of coalescent mastoiditis (Fig. 110.2), and it is an extremely important finding for anticipating likely intracranial complications.

Acute otomastoiditis will often be in its coalescent state within the thin trabecular bone of the mastoid air cells when it comes to imaging. The mastoid cortical bone may appear irregular and indistinct, either increased in density due to necrosis bone or frankly eroded. Early changes of the septae within the mastoid are not particularly reliable for making a definitive diagnosis of coalescent mastoiditis, which is a disease usually managed in part by surgical drainage (Fig. 101.2). However, erosion of bone along the sigmoid plate or of the outer cortex of the mastoid is highly reliable for suggesting the infection has reached the point that surgical drainage will be a necessary part of treatment.1

FIGURE 110.1. A–D: Acute mastoiditis, usually secondary to acute suppurative otitis, causes opacification of the middle ear cavity and the mastoid air cells as seen on these axial computed tomography images (A, B). Note how even the most gracile of the ossicles, the incus long process (arrow), and the stapes posterior crus (arrowhead) are still visible in (B). The indistinct septae of the mastoid (arrowheads in A) are not diagnostic of coalescent mastoiditis. This patient responded completely to antibiotic therapy. Acute otomastoiditis may also occur with little or no evidence of middle ear disease if there is a mucosal block in the aditus ad antrum (C, D).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree