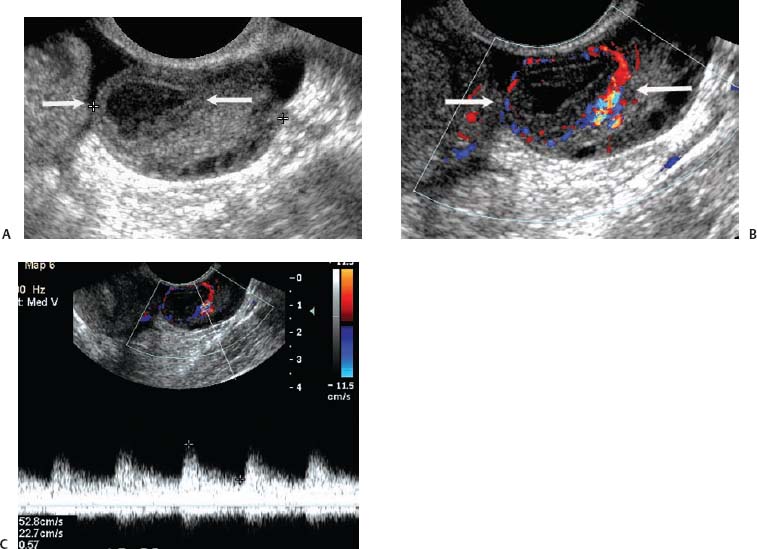

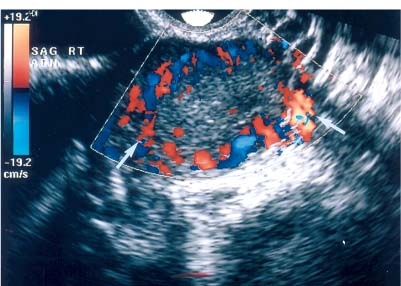

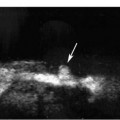

8 Acute Pelvic Pain Acute pelvic pain is a common problem seen in everyday practice. There are multiple possible causes of acute pelvic pain, and a quick, cost-effective evaluation is desirable for timely diagnosis. Because ultrasound can distinguish between many of the diagnostic possibilities noninvasively, it is the preferred initial imaging modality performed to evaluate this condition. This chapter addresses the role of ultrasound in the clinical evaluation of acute pelvic pain. The value of other diagnostic modalities is also discussed. Causes of acute pelvic pain can be divided into gynecologic and nongynecologic etiologies. Gynecologic causes of pelvic pain include ovarian cysts, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, and ovarian torsion. Less commonly, benign or malignant adnexal masses, such as fibroids or ovarian cancer, and endometriosis, may produce acute pelvic pain. Nongynecologic causes of pelvic pain include appendicitis, urinary calculi, mesenteric adenitis, inflammatory bowel disease, bowel obstruction, metastatic disease, and diverticulitis. The evaluation of the patient with acute pelvic pain begins with the clinical history and physical examination. The value of any imaging technique is enhanced by the addition of clinical information. Because multiple disease processes may present with a similar clinical syndrome, the differential diagnosis is constructed from data obtained from the clinical history, including the age of the patient and menopausal status. The duration and recurrence of the problem as well as current medications are important considerations. Significant historical information concerning prior urinary or gynecologic problems also guide the diagnostic evaluation. For example, a prior history of ectopic pregnancy will focus the workup to exclude recurrence of the disease. This diagnostic evaluation is also supported by the physical examination. The location of pain as well as signs of pelvic mass limit the differential diagnoses. Signs of infection, including fever and rebound tenderness, suggest inflammatory etiologies such as appendicitis or tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA). Sudden decrease in blood pressure or change in mental status portend more serious conditions prompting immediate diagnostic or surgical examinations. The differential diagnosis is also informed by laboratory information. Hematologic and blood chemistry studies are obviously important tools to determine the origin of pain. An elevated white blood cell count and sedimentation rate support an infectious or inflammatory etiology for pain. Abnormal renal or liver function tests may suggest a specific cause for pain or point to a generalized process such as diffuse metastatic disease. Urine or serum pregnancy tests are essential in premenopausal patients, whereas serum tumor markers may be helpful in postmenopausal women. Ultrasound is the primary imaging modality utilized to distinguish between the different causes of acute pelvic pain. It is a noninvasive examination with no known adverse effects. Other advantages of ultrasound include ready availability, low cost, and high sensitivity for many disease processes. Endovaginal sonography (EVS) has proven highly accurate for the diagnosis of many gynecologic conditions. EVS offers improved visualization of the pelvic structures compared with the transabdominal approach. EVS demonstrates adnexal masses, collections, free fluid, hydroureter, and other important clues to diagnosis. Duplex and color flow Doppler techniques demonstrate physiological as well as anatomical information and may provide important diagnostic clues. Detection of tissue vascularity and characterization of specific flow patterns improve diagnostic accuracy and provide specific findings not possible with gray-scale imaging alone. For example, the detection of high-velocity, low-resistance flow signals allows the detection of placental flow in the uterus and adnexa even in the absence of significant gray-scale information. Conversely, the absence of ovarian flow is consistent with ovarian torsion. The most common gynecologic cause of acute pelvic pain is the growth of ovarian cysts. The occurrence of pain is closely associated with follicular rupture during the mid-portion of the menstrual cycle.1 Mittelschmerz (middle pain) was initially thought to be due to peritoneal irritation from release of blood and follicular contents during ovulation. This coincides with follicle-stimulating hormone/luteinizing hormone (FSH/LH) surge during days 14 through 16 of the menstrual cycle. Sonographic monitoring of midcycle ovaries has shown that the symptoms precede follicular rupture in 97% of cases.2,3 The pain is usually noted on the side of the dominant follicle and is probably related to follicular enlargement. Figure 8–1 Ovarian cyst. A well-circumscribed cyst is identified within the ovary. Note the thickened rim (arrows) surrounding the cyst and the echogenic focus (curved arrow) consistent with the cumulus oophorus. Characteristic sonographic findings are associated with the periovulatory period. Prior to ovulation, the mature follicle demonstrates a mean diameter of 20 to 24 mm.4,5 The cyst will demonstrate an echogenic rim (Fig. 8–1). Irregularity of the inner lining of the cyst may be seen when ovulation is imminent.1 A small echogenic focus or rim may be seen along the wall of the mature follicle. This represents the cumulus oophorus and confirms that the follicle contains the oocyte. Ovulation usually occurs within 36 hours of visualization of the cumulus oophorus. Following ovulation, the size of the follicular cyst usually decreases. Fluid is commonly seen in the cul-de-sac and surrounding adnexae. This is thought to be due to exudation from the ovary and has been measured to be ~15 to 25 mL at laparoscopy.6 Color and pulsed Doppler examination of the mature follicle demonstrates a rim of increased vascularity surrounding the cyst (Fig. 8–2). This is best visualized during endovaginal color flow imaging and is helpful in the identification of the corpus luteum.7 The ring of vascularity (“ring of fire”) is initially seen during day 8 of the menstrual cycle and continues through day 24. Although the ring of fire sign was originally described for the peripheral vascularity associated with an extrauterine gestational sac, the appearance is routinely identified in corpus luteal cysts. Peripheral vascularization of the corpus luteum may persist through the first trimester. Figure 8–2 Corpus luteum. (A) A complex cyst (arrows) is seen with internal echoes consistent with hemorrhage. (B) Color Doppler demonstrates peripheral vascularity (arrows) in a “ring of fire” pattern, consistent with a corpus luteal cyst. (C) Pulsed Doppler reveals high velocity, low impedance flow during sampling of the corpus luteum. Figure 8–3 Hemorrhagic luteal cyst. A ring of vascularity (arrows) surrounds the hemorrhagic corpus luteum, which is isoechoic to the ovarian parenchyma. Color Doppler aids in the identification of the hemorrhagic corpus luteum. The cystic component may not be visualized if the hemorrhage within the cyst is isoechoic to the adjacent ovarian parenchyma. Increased vascularity is identified around the periphery of the isoechoic ovarian mass (Fig. 8–3). The detection of vascularity in the rim of the cyst, and not in the hemorrhagic component, is an important discriminator between a complex cyst and a solid ovarian mass. The finding of peripheral vascularity in a complex midcycle cyst warrants interval follow-up in 4 to 6 weeks, during the first week of a subsequent menstrual cycle, to confirm interval resolution of the cyst. Pulsed Doppler sampling of the corpus luteum reveals higher-velocity, low-impedance flow from the vascular ring.8 Dillon et al demonstrated a peak systolic velocity of 27 ± 10 cm/s and resistive index (RI) = 0.44 ± 0.09 for corpus luteal flow.9 This low-impedance flow pattern should not be confused with low-resistance flow associated with ovarian cancer. The pain associated with formation of the dominant follicle and ovulation is self-limited, not requiring treatment in most cases. Ectopic pregnancy is one of the most common indications for pelvic sonography in patients with acute pelvic pain. Ectopic pregnancy represents approximately1 4% of all reported pregnancies, with 75,000 cases occurring in the United States each year.10 The risk of maternal death from ectopic pregnancy is 10 times greater than that from natural childbirth. Important risk factors include pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, prior tubal surgery and prior ectopic pregnancy. This is probably related to mechanical obstruction of the fallopian tube. Other risk factors include in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer as well as ovulation induction with gonadotropins. Less than 50% of patients present with the classic clinical presentation of adnexal pain, pelvic mass, and vaginal bleeding.11,12 Patients typically present with one or more of these nonspecific signs or symptoms. The menstrual history and pregnancy test are essential in the evaluation for ectopic pregnancy. A positive pregnancy test increases the suspicion for ectopic pregnancy. The differential diagnosis includes threatened abortion and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Prompt sonographic examination is indicated to diagnose ectopic pregnancy because delayed diagnosis may result in life-threatening hemorrhage from tubal rupture. Endovaginal sonography is the preferred initial examination because it can diagnose intrauterine and ectopic pregnancy earlier than the transabdominal approach.13–15 Culdocentesis is no longer considered a first-line diagnostic examination because a negative test does not exclude ectopic pregnancy. Uterine curettage and laparoscopy are useful but should be delayed pending the sonographic results. The definitive diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is made based on the observation of an extrauterine embryo or fetal cardiac pulsations (Fig. 8–4). If these findings are not identified, then a thorough evaluation of the uterus, adnexae, and cul-de-sac is performed to look for other evidence of pregnancy. The uterus is evaluated first for evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy. If an intrauterine pregnancy is identified, then the likelihood of a concomitant or heterotopic ectopic pregnancy is low, occurring in one of 30,000 spontaneous pregnancies. The frequency of heterotopic pregnancy increases if the patient has undergone ovulation induction. If the uterus fails to demonstrate evidence of pregnancy, the adnexae are carefully surveyed for signs of ectopic pregnancy. Other possibilities include a complete abortion or very early intrauterine pregnancy (less than 5 weeks gestational age). Careful correlation with menstrual data and serum human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) titers is helpful in distinguishing these entities. A subnormal rise or plateau of the serum HCG titers suggests a diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Figure 8–4 Ectopic embryo. An embryo (arrow) is identified within the ectopic gestational sac. Cardiac activity was noted. An abnormal sac in the endometrial canal may represent an abnormal intrauterine pregnancy such as an incomplete abortion or a pseudogestational sac associated with an ectopic pregnancy. Duplex and color Doppler can distinguish these entities by demonstrating placental flow.16 Endovaginal color flow imaging demonstrates placental flow as an area of increased vascularity around the periphery of the true gestational sac. Taylor et al described placental flow as a relatively high-velocity, low-impedance signal localized to the site of placentation during pulsed Doppler sampling.17

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Evaluation

Nonimaging Tests

Ultrasound Imaging

Ovarian Cysts

Ectopic Pregnancy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree