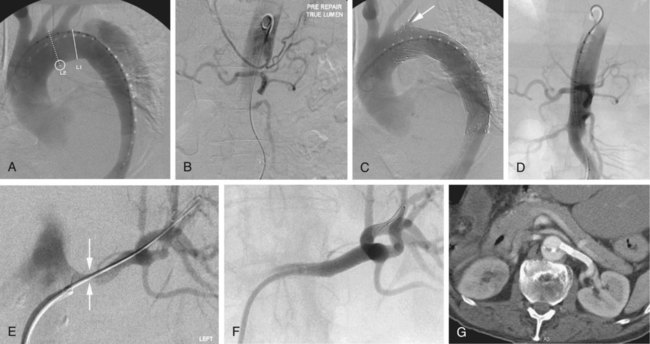

Acute renal ischemia is defined as diminished renal excretory function as a result of acutely impaired renal perfusion.1 The common etiologies causing acute renal ischemia are listed in Table 59-1. Patients present with acute renal insufficiency if they suffer acute bilateral renal hypoperfusion or acute hypoperfusion to a solitary functional kidney. Acute renal artery occlusion may also present with acute loin pain and hematuria, particularly if due to traumatic or embolic etiologies. The degree of renal parenchymal ischemia is influenced by the severity and chronicity of renal artery occlusion. These parameters may also influence management decisions. For example, patients with a background history of atherosclerotic renal artery stenoses and well-formed collaterals may benefit from recanalization of a chronic complete renal artery occlusion. Patients with acute renal artery occlusion without collateral formation are less likely to benefit from delayed revascularization. Endovascular revascularization techniques are not commonly used for most causes of acute renal ischemia but may provide major benefits for the patient in certain specific situations. The indications for endovascular intervention in the setting of acute renal ischemia are listed in Table 59-1 and will be described separately. Renal artery trauma is a rare complication of blunt abdominal trauma (0.08% of blunt trauma hospital admissions), but is increasingly recognized with routine use of computed tomography (CT) in the trauma setting.2 It is frequently associated with other injuries.3 The most common arterial injury is traumatic dissection, which is often associated with partial or complete arterial occlusion. Complete arterial avulsion is less common. Hemodynamically stable patients with unilateral renal artery trauma may be managed conservatively, with a 6% risk of development of renovascular hypertension.2 Surgical repair of main renal artery injuries should only be undertaken if there is bilateral injury or a solitary kidney4 and should be performed urgently to preserve renal function. Open surgical revascularization techniques include thrombectomy, direct arterial repair, and bypass grafting using synthetic or vein grafts. The results of surgical revascularization have been poor, with preservation of renal function achieved in only a minority of patients.5 Endovascular techniques, including thrombolysis6,7 and stenting,7,8,9 have been described but have been used sparingly. The proposed indications include patients with unilateral renal artery trauma or in whom open surgical repair is contraindicated. Frequently these patients are undergoing catheter-directed intervention to manage traumatic injuries elsewhere.10 The most common reported technique is stenting of an occluded or dissected (but patent) renal artery, either with a bare metallic or covered stent. In the setting of a totally occluded renal artery, it is unclear whether there is complete avulsion or traumatic dissection with intact arterial wall layers. In the event of free arterial bleeding after stenting, the interventionalist should be prepared to embolize the artery.10 Renal arterial thromboembolism is uncommon, with most emboli of left atrial origin in patients with atrial fibrillation.11 Patients usually present with colicky loin pain.11 Revascularization should occur urgently because acute complete renal ischemia can produce irreversible kidney damage in 60 to 90 minutes. However, treatment may be worthwhile after 90 minutes because embolic occlusion may be incomplete in some cases.11 Endovascular techniques have only been described in sporadic case reports12 and have included aspiration thrombectomy and thrombolysis. The causes of acute renal ischemia in a setting of renal artery atherosclerosis are listed in Table 59-2. Hemodynamically significant renal artery stenoses frequently progress, with risk factors for progression including severe stenoses, high systolic blood pressure, and diabetes mellitus.13,14 Progression to occlusion is associated with loss of renal mass and decreased renal function.15 Rapid progression of an atherosclerotic stenosis usually occurs secondary to plaque dissection, resulting in a critical stenosis or total occlusion. In this situation, renal artery revascularization is indicated, particularly if the relevant renal artery supplies a solitary functional kidney (Fig. 59-1). It is useful to have any recent imaging available that demonstrates a patent renal artery and reasonable renal size.16 TABLE 59-2 Etiology of Acute Renal Ischemia in Renal Artery Atherosclerosis A more common cause of acute renal ischemia in patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis is the institution of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB). It is normal for patients to experience a minor rise in serum creatinine (<20% above baseline) once an ACEI/ARB is introduced. However, patients with significant underlying renal hypoperfusion may suffer a more severe acute decline in renal function.17 These patients are ideal candidates for revascularization (Fig. 59-2).18 Early experience of endografting for acute type B aortic dissection has proved promising for reducing false lumen perfusion and pressurization, particularly in the thoracic aorta.19 The primary treatment goal of endoluminal repair is to exclude the primary inflow intimal tear. Type B aortic dissection frequently involves the renal arteries, but significant acute renal ischemia is less common. This may be due to dynamic obstruction due to compression of the aortic true lumen (Fig. 59-3) or static renal artery obstruction where the dissection extends into the renal arteries themselves. These patients present with ongoing hypertension and acute renal impairment. Renal ischemia usually responds to endograft closure of the proximal main entry tear, although other procedures such as renal artery stenting may also be required to restore renal perfusion. Stenting of atherosclerotic stenoses of the renal artery ostium is associated with improved procedural success, patency, and reduced restenosis rates20,21 when compared with angioplasty alone. For this reason, primary stenting of ostial atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis is considered the treatment of choice, with angioplasty reserved for non-ostial atherosclerotic stenoses and stenotic disease due to other pathologies such as fibromuscular dysplasia.22 If angioplasty is performed, complications such as arterial dissection or elastic recoil with residual stenosis are important indications for secondary stenting.23 Complications after renal artery stenting may also result in acute renal ischemia. These include arterial rupture, stent fracture,24 dislocation of mural thrombus,25 and incomplete stent deployment with residual stenosis and thrombosis.26 All of these conditions require secondary intervention. A rare complication of endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair is proximal malposition of the endograft, resulting in inadvertent coverage of the main renal artery ostium and acute renal ischemia. This can often be managed by endovascular techniques (Fig. 59-4

Acute Renal Ischemia

Indications

Renal Artery Trauma

Renal Artery Thromboembolism

Acute Ischemia in Renal Artery Atherosclerosis

Aortic Dissection with Renal Hypoperfusion

Renal Artery Occlusion After Endovascular Intervention

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Acute Renal Ischemia