and Gustavo Marino2

(1)

Attending Physician VA Medical Center, George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

(2)

Chief Gastroenterology Section VA Medical Center, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

7.1.1 Anatomy and Technique

7.2.1 Adrenal Biopsy

7.2.3 Paraganglioma

7.2.4 Accessory Spleen

7.2.5 Ascites

7.2.6 Omentum

7.2.7 Fluid in the Lesser Sac

7.2.8 Mesenteric Cysts

7.2.9 Omental Cake

7.2.10 Peritoneal Carcinomatosis

Abstract

The adrenals, spleen, and peritoneal structures each do not supply enough material for separate chapters of their own; this is the only reason they are combined here. Visualization of the adrenal glands by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has been demonstrated for almost two decades; a reliable approach to the left adrenal gland was initially reported by Chang et al. [1] in 1996. More recently, several groups have shown several techniques that allow visualization and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the right adrenal gland, as described below.

7.1 General Principles

The adrenals, spleen, and peritoneal structures each do not supply enough material for separate chapters of their own; this is the only reason they are combined here. Visualization of the adrenal glands by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has been demonstrated for almost two decades; a reliable approach to the left adrenal gland was initially reported by Chang et al. [1] in 1996. More recently, several groups have shown several techniques that allow visualization and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the right adrenal gland, as described below.

A careful examination of adrenal glands is frequently requested by referring providers to rule out metastatic disease, evaluate imaging abnormalities or masses, or obtain tissue by FNA.

The spleen can be easily found from the proximal part of the stomach, opposite the liver and above the kidney. The splenic hilum can be found following the splenic vein by clockwise torque and slight withdrawal of the echoendoscope.

7.1.1 Anatomy and Technique

The left adrenal gland can usually be found from the proximal part of the stomach, adjacent to the upper pole of the left kidney, between the kidney and the aorta. Both radial and linear scanning echoendoscopes can be used to visualize it.

The EUS approach to the right adrenal gland is more challenging and has been described from the antrum, duodenal bulb, and descending duodenum by different authors. Preference of technique depends on local expertise; a scanning frequency of 5 MHz is recommended for better visualization of deep landmark anatomic structures. Examination from the duodenal bulb requires a linear scanning echoendoscope [2]. The endoscope is positioned in the duodenal bulb with a long gastric approach; once the portal vein is visualized, a longitudinal view of inferior vena cava (IVC) can be found by clockwise rotation and elevation of the tip of the endoscope. The IVC can be traced toward the hilum to detect the right adrenal gland. The adjacent upper pole of the right kidney can be found by rotating the endoscope. Uemura et al. [2] reported successful visualization of the right adrenal gland in 87 % of patients (131/150) with this technique.

Visualization of the right adrenal gland from the second portion of the duodenum starts with identification of the right kidney by linear scanning EUS. Slow withdrawal of the endoscope for a few centimeters with counterclockwise torque may provide visualization of the adrenal gland, often behind the IVC. Additional gentle maneuvering can provide a safe window between the inferior margin of the liver and the IVC for detailed examination and FNA [3].

Another approach to visualize the right adrenal gland from the antrum has been described by Dietreich and Kann [4]. The tip of the endoscope is placed in the antrum, in front of the pylorus, and the patient is turned into the right decubitus position. The endoscope is flexed toward the right, leaning behind the angular notch, and is gently retracted to find the landmark structures: the upper pole of the right kidney, IVC, portal vein, and margin of the liver. The right adrenal gland can then be found behind the IVC.

While ascites is a frequent finding on EUS exams, more localized collections, for example, in the lesser sac, are less frequently encountered and may raise unique differential diagnostic possibilities. These collections can easily be aspirated with EUS-FNA, and this could effect the management of patients, particularly if malignant cells are found. The normal omentum is rarely observed during EUS exams, but familiarity with its appearance on ultrasound may avert misinterpretation when it becomes visible. Cases with mesenteric cysts and different forms of peritoneal carcinomatosis conclude this chapter.

Box 7.1: Resources

NIH State-of-the-Science Conference 2002: Management of the Clinically Inapparent Adrenal Mass (Incidentaloma) http://consensus.nih.gov/2002/2002AdrenalIncidentalomasos021Program.pdf

“The Incidentally Discovered Adrenal Mass.” Review article (full online access provided by the New England Journal of Medicine) http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMcp065470

DAVE Project – Gastroenterology: Ascites – Malignant Ascites EUS FNA: http://daveproject.org/ascites-malignant-ascites-eus-fna/2003-12-05/

7.2 Cases and Discussions

7.2.1 Adrenal Biopsy

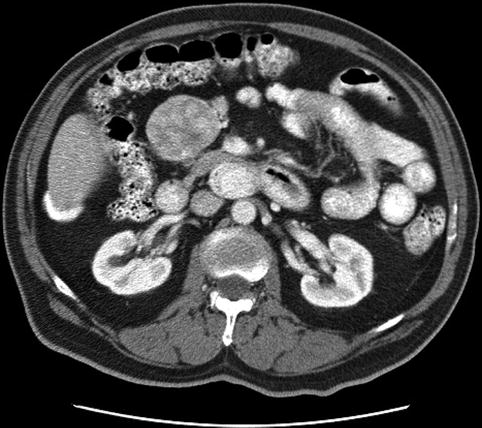

This is a 46-year-old woman who presented initially with hematuria. As part of the workup, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen was performed and showed a pancreatic cystic mass. The patient was referred for EUS evaluation. The EUS showed a solid lesion instead but it was not clear whether it was coming from the pancreas, adrenals (no normal adrenals were seen on EUS), or – least likely –the kidney. A FNA biopsy was performed and the cytology was most consistent with a benign adrenal adenoma. This was an unplanned adrenal biopsy but it obviously helped to reassure the patient and referring physicians.

Fig. 7.1

Four-centimeter-diameter mass between the pancreas and kidney on computed tomography

Fig. 7.2

Computed tomography with coronal reconstruction showing a mass between the pancreas and kidney

Fig. 7.3

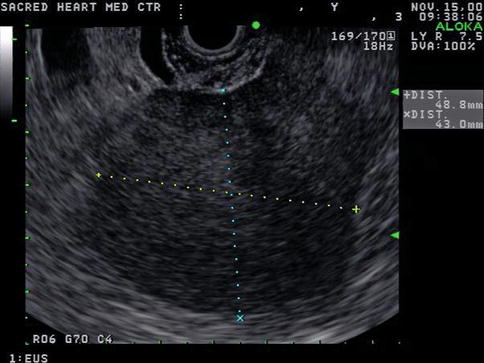

Endoscopic ultrasound appearance of the mass between the left kidney (L KID) and pancreas

Fig. 7.4

Another view of the 4-cm-diameter adrenal mass

Adrenal masses, defined as lesions with a diameter of 1 cm or more [5], can be found incidentally on EUS in patients evaluated for another reason. The prevalence of these lesions is markedly increased in older individuals. In these cases the endoscopist must obtain all the information that EUS can provide. Size of the mass, shape, definition of margins, and sonographic pattern are key predictors of malignant disease, as discussed below. Eloubeidi et al. [6] have reported that altered adrenal shape correlates better with probability of malignancy than size or echogenic pattern. A clear understanding of the differential diagnosis and the current approach to these lesions is necessary to optimize the role of EUS and avoid inappropriate manipulation if it is not indicated.

In patients with an adrenal mass and known malignancy (including lung, kidney, breast, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, and liver tumors) the probability of adrenal metastases increases to approximately 50 % [7]. In these cases the diagnosis cannot be made with imaging alone. Biopsy is also usually necessary when bilateral involvement is present; however, management is not clear in those with unilateral involvement, and surgical resection without biopsy may be considered.

The most common adrenal incidentalomas include adrenocortical adenomas, adrenocortical carcinomas, metastases, myelolipomas, pheochromocytomas, adrenal cysts, ganglioneuromas, and infectious lesions.

Adrenocortical adenomas typically have a slow growth rate, less than a centimeter per year, reaching a total diameter no larger than 3 cm, and have a well-defined round or oval smooth margin. Nonhypersecreting, benign adrenocortical adenomas are the most common type of adrenal incidentaloma.

Adrenocortical carcinomas usually have an irregular margin and heterogeneous density because of areas of necrosis, hemorrhage, and calcifications and can grow rapidly, reaching large diameters (>4 cm).

Metastasis to the adrenal gland frequently occurs as bilateral lesions of variable growth rate and size.

Myelolipomas are lesions formed by myeloid, erythroid, and adipose tissue. Fat can be identified on imaging studies including EUS, giving them a typical appearance, as shown in the following case 7.2.2.

Pheocromocytomas also have a round or oval shape but may develop cystic changes and hemorrhage. Their rate of growth is slow but they can reach large diameters (>4 cm) [5].

Infectious lesions include tuberculosis, fungal infections (such as histoplasmosis, coccidiomycosis, blastomycosis, parasitic infections), cytomegalovirus, and bacterial abscess.

Full access to an excellent review of this topic is available at the New England Journal of Medicine website (see Box 7.1). Important questions about the management of this entity are controversial, and there are no comprehensive guidelines. The 2003 National Institutes of Health state-of-the science statement [8] was an attempt to define this problem and its management options, but only limited information regarding the role of EUS was available at that time, and the role of EUS-guided FNA has not been standardized. More recent publications have reported a better yield with EUS-guided biopsy than with CT-guided percutaneous FNA/biopsy, with comparable safety. We recommend that endosonographers establish discussion and communication with endocrinologists and specialized surgeons to develop a clear protocol. Evaluation of hormonal activity by focused history, physical examination, and laboratory testing is the first step in the evaluation of these lesions.

EUS-guided FNA sampling of the left adrenal gland is not difficult, and its safety and effectiveness have been reported multiple times [9]. EUS imaging and FNA of the right adrenal gland is more challenging, but excellent safety and diagnostic results also have been reported by EUS experts [2, 3, 6]. EUS-guided FNA minimizes the length of the needle path, traversing only the wall of the stomach or duodenum and avoiding vascular structures and the pancreas, spleen, liver, and lungs; therefore it is considered a safer technique than CT-guided FNA [2, 6], which can cause pneumothorax, hemorrhage, pancreatitis, needle track seeding, and abscess.

Some important points to remember include the following:

Most adrenal incidentalomas do not require tissue sampling.

FNA may be indicated in cases suspicious for malignancy or infectious cause if imaging diagnosis is not sufficient.

Pheochromocytoma should be ruled out before FNA to avoid a hypertensive crisis.

7.2.2 Myelolipoma Inside an Adrenal Adenoma

This is a 66-year-old patient with a known stable adrenal adenoma. She was referred for the evaluation of one episode of acute pancreatitis with unclear etiology. EUS shows the adrenal adenoma, which contains two internal, spherical, echogenic structures consistent with myelolipomas of the adrenal gland. The exam of the pancreas was unremarkable.

Fig. 7.5

Adrenal myelolipoma

Fig. 7.6

Adrenal myolipoma (close-up)

Adrenal myelolipoma is a rare benign neoplasm composed of mature adipose tissue and a variable amount of hematopoietic elements. Most lesions are small and asymptomatic, discovered incidentally at autopsy or on imaging studies performed for other reasons. The sonographic appearance varies with the composition of the neoplasm. If the tumor contains predominantly fatty components, it appears uniformly hyperechoic. If the tumor contains a predominance of myeloid cells, it may appear heterogeneous or hypoechoic.

7.2.3 Paraganglioma

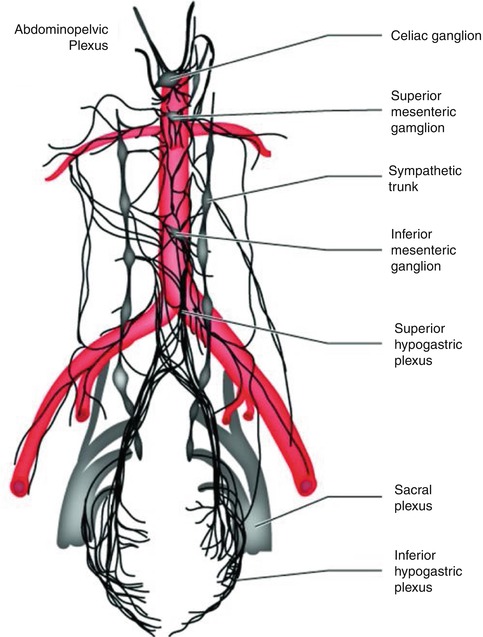

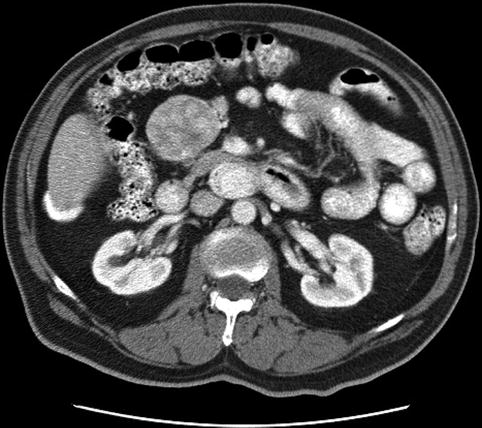

This is a 72-year-old man with well-controlled hypertension who was incidentally found to have a large peripancreatic mass. The CT scan shows inhomogenous enhancement and the EUS shows a hypoechoic, spherical, well-circumscribed tumor separate from the pancreas. The FNA aspirate was unusually bloody, confirming the vascular nature of the neoplasm. A neuroendocrine tumor was suspected. The cytology was nondiagnostic and the tumor was surgically excised. The final histology – confirmed by outside consultation – was consistent with a paraganglioma/pheochromocytoma.

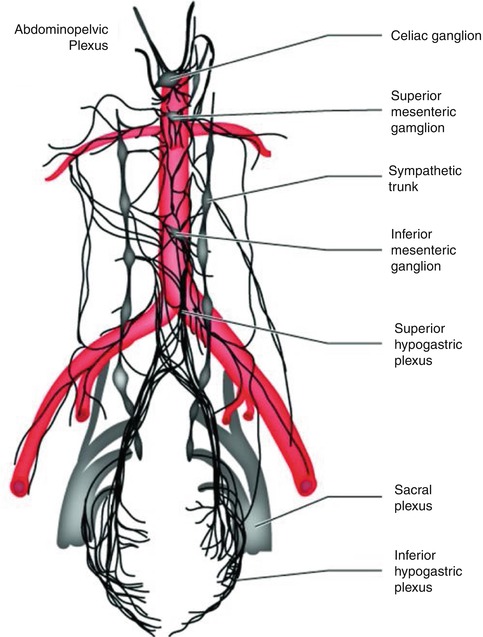

Fig. 7.7

The abdominopelvic autonomic nervous system. The abdominopelvic plexus can be seen as a complex network of fibers wrapped around the anterior and lateral aspects of the abdominal aorta, dividing just below the aorta to course into the endopelvic fascia of the pelvic basin (From Willard and Schuenke [10])

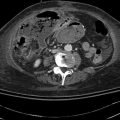

Fig. 7.8

Paraganglioma on computed tomography