, Yves Etienne2 and Maurice Niddam3

(1)

Faculté de Médecine, Marseille, France

(2)

Unité de Médecine Légale, Hôpital de la Timone, Marseille, France

(3)

Unité SAMU 13, Centre 15, Hôpital de la Timone, Marseille, France

This is the history of successive discoveries which allowed the identification of anatomical organs and systems involved in any emotional process.

Our elders had good knowledge of emotions. They were even capable of arousing them to entertain an audience. This is shown in the theatre and especially Greek tragedies, with expressive masks worn by the actors and scary stories with a preposterous mythological basis.

But, most people believed that the emotion organ was the heart. However, the well-known physicians and philosophers of the Antiquity did not all share the same beliefs. Thus, Hippocrates (460–370 BC) believed that passions, feelings and emotions were controlled by the brain. A few years later, Aristotle (384–322 BC) referred back to the primacy of the heart which governs, according to him, all mental activity, including thoughts. The work conducted by Galien (131–204 AC) on animals was however going to confirm the hippocratic theory by declaring that the brain is “where the directing mind resides”.

The Middle Ages suffered from obscurantism and numerous prohibitions. As a result, nearly no progress was made regarding knowledge of the human body and brain, and the rare anatomists of this era, such as Berengario da Carpi (1460–1530), simply based their work on Galien’s models.

We had to wait for the Renaissance and its series of discoveries for the scientific study of the brain to finally begin. Anatomical dissections were firstly performed secretly by several audacious scientists. This is supported by the remarkable sketches of the brain by Leonard de Vinci (1452–1519). Such dissections were then authorised. The anatomy era could thus begin, and representations of dissected human brains were going to appear in anatomical books by authors such as Charles Estienne (1504–1564) or André Vesale (1515–1564) in his “de Humani corporis fabrica”, published in 1543. With this remarkable book and anatomy lessons based on real dissections, Vesale was going to establish the basis of modern anatomy.

During the seventeenth century, although the anatomy of the nervous system was slowly developing, the role played by the brain was still going to be a major source of philosophical discussions, and the term “heart” was going to be used instead of affective brain.1 René Descartes (1596–1650) prepared a theory which dissociates the body, whose operation is governed by humours, and the mind, whose mental functions are governed by God and which are joined together by the epiphysis or pineal gland.

Thomas Willis (1621–1675) who was going to discover the vascular polygon at the basis of the brain, rejected Descartes’ theory. As a result, he proposed a new theory in his book de Cerebri Anatome (1664). According to him, the memory and will are located in the cortex, imagination is located in the corpus callosum and sensations in the corpora striata! It is also Thomas Willis2 who first introduced the notion of “limb” which is employed to refer to the medial surface of the cerebral hemisphere. This term was to be shortly reused by Thomas Bartholin in 1677. Despite all of the controversy surrounding the Cartesian theories, the brain still played its predominant role. Among Descartes critics, two philosophers are to be mentioned: John Locke (1632–1704) and Etienne Bonnot De Condillac (1715–1780), for whom the brain is the organ which collects “ideas of sensation” and which adjusts “ideas of reflection”.

During the eighteenth century, the study of the nervous system at a general level and of the brain, in particular, was to be developed via numerous discoveries:

In the physiology of the nervous system with Felix Vicq d’Azyr (1746–1794), with Albrecht von Haller (1757–1766) and then with Pierre Flourens (1794–1867)

In nervous electrophysiology with Luigi Galvani (1737–1798)

In anthropology and evolution, with the remarkable work performed by Jean Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) concerning the evolution of species and their respective brains

In neuroanatomy, with Giovanni Domenico Santorini (1681–1778) and then Samuel Thomas von Sömmering (1755–1830)

However, it was during the nineteenth that the most progress was made in neuroanatomy and histology of the nervous system, in particular with the beginning of the discovery of the brain of emotions:

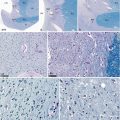

Remarkable biologists studied nervous tissue with a microscope. Theodor Schwann (1810–1882) showed that this tissue is an assembly of nervous cells. Then came the specific colouration of nervous cell nuclei by Franz Nissl (1860–1919), the colouration of nervous cells with their extensions by Santiago Ramon y Cajal (1852–1934) and the specific study of cell layers by Vladimir Betz (1834–1894) and Korbinian Brodmann (1868–1910) whose cytoarchitectonic map of the cortex is still used at present!

Well-known neurologists became the founding fathers of modern neurology: this especially concerns Jean Martin Charcot (1824–1893), who, through is research on hysteria, showed that the brain is where emotions are expressed and that many disruptions in this field are the cause of numerous pathologies.

In neurophysiology, François Magendie (1783–1855) continued the work of his teacher, Flourens, and studied cerebral locations by observing the results of electrical stimulation of the cortex.

Extremely well-known anatomists have focused on the brain and nervous system, especially Friedrich Arnold (1803–1890), Sir Charles Bell (1774–1842), Auguste Forel (1848–1931), Achille Louis Foville (1799–1878), Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828), Friedrich Goll (1829–1903), Louis-Pierre Gratiolet (1815–1865), Johannes Bernhard Aloys von Gudden (1824–1886), François Magendie (1783–1855), Théodore Hermann Meynert (1833–1892), Johann Christian Reil (1759–1813) and Luigi Rolando (1773–1831), Ludwig Türck (1810–1868) and Sir William Turner W. (1832–1916).

Two anatomists, one who is German, Karl Friedrich Burdach (1776–1847)3, a professor of physiology, and the other who is French, Paul Broca (1824–1880), a physician and anthropologist, made remarkable discoveries which became the foundation of the brain of emotions:

The first anatomist, in his remarkable work (Burdach KF, 1818–1826) covering 3 volumes, entitled “Vom Baue und Leben des Gehirns und Rückenmarks”, provides an initial description and the first illustration of the amygdaloid body whose presence is shown on a coronal section.

The second anatomist, who discovered, in 1861, the articulated language area4, which bears his name (area of Broca)5, and who revealed the “concept of hemispheric dominance”, will be the first to describe what he will call the “limbic lobe” during a conference given at the Society of Anthropology of Paris and published in the “Revue d’Anthropologie” in 1878 6

At that stage, the developing science of neuroanatomy included the anatomy of emotions in its scope of exploration. Successively William James7 and Carl Lange8 developed, in 1884 and 1885, respectively, each working alone, the first theory of emotions which was soon to be unified in scientific circles under the theory of James–Lange: for these authors, emotion is the response to corporal modifications and reactions triggered by an emotional stimulus. If I am sad, it is because I am crying. It is not because when we see a bear, we are afraid and cry; it is because we run when we see a bear that we are afraid. “My theory … is that the bodily changes follow directly the perception of the exciting fact and that our feeling of the same changes as they occur, is the emotion” (Lange).

The twentieth century appears to be promising for research work conducted on the nervous system. During the first part of the century, very well-known scholars from diverse and complementary fields emerged. They were to become the protoresearchers in neurosciences. They included:

Neuroanatomists: Paul Emil Flechsig (1847–1929) and James Papez (1883–1958)

Neurologists among which Joseph Dejerine (1849–1917) and his wife, Augusta Klumpke (1859–1927); remarkable clinicians as well as researchers; and Henri Gastaut (1915–1995), the French pioneer in electroencephalography

Psychoanalysts with Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) and all of their thought trend which was expressed via the various psychoanalytical societies.

Embryologists, including Constantin von Monakow (1853–1930) who performed remarkable work on the myelogenesis

Psychiatrists, such as Christfried Jakob (1866–1956), who is mentioned at the same time as Papez concerning the complementarity of their research

Neurosurgeons including Harvey Cushing (1869–1939), a pioneer in brain surgery, Otfrid Foerster (1873–1941) and Wilder Penfield (1891–1976), whose experience in peroperative cortical stimulation experiments were to develop knowledge of the cortical areas

Talented neurophysiologists including Albert von Kölliker (1817–1905), Luigi Luciani (1840–1919), author of a remarkable monograph concerning the cerebellum, or even Hermann Munk (1839–1912), known for his work carried out on the occipital lobes and vision

Psychologist physicians among which we must mention Pierre Janet (1859–1947), who continued the work of Charcot

All along the twentieth century, the brain and the whole nervous system are going to be better known thanks eminent elders, of which we have only mentioned a few who were especially involved in the development of knowledge.

However, at the same time, serious invalidating pathologies have appeared in the population whose lifetime is extending (Alzheimer9, etc.). We must therefore accept the challenge, and this is an opportunity to widen our scope of research by providing the many researchers in all newly developing sectors in the field of neurosciences, with diverse and generally converging research possibilities.

And although the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases remains disappointing, the research results that they have generated and which are still being obtained are extremely remarkable:

Extraordinary and new technologies especially appeared in the field of imaging (electroencephalography, evoked potentials, MRI, magnetoencephalography, functional MRI, stereotaxic exploration) and the engineers and technicians are improving them on a continuous basis.

Progress also concerns new approaches which have become actual specialities in the large field of neurosciences, neurobiology (within France, Jean-Pierre Changeux and Marc Jeannerod), neuroendocrinology, neuropharmacology, neuropsychology, neuropathology, neuropsychiatry and philosophy of neurosciences.

As for the older sectors of neurosciences, several have been modified and enriched: thus, neurophysiology, which integrates all neuro-immunology methods and which now benefits from electrophysiology techniques; neuroanatomy which benefits from neural tracing; and neuro-histology which can use the data provided by neuro-cytology, immunohistochemistry, immunostaining and electronic microscopy. Embryology, which is now known as “neurodevelopment”, now covers a large sector including neurogenesis, apoptosis, neurotrophins, neural migration, synaptic plasticity and neurosurgery with new techniques of awake brain surgery.10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree