Indications and Assessment for Liver Transplantation

Introduction

Liver transplantation is now widely accepted as an effective therapeutic modality for a variety of irreversible acute and chronic liver diseases for which there was formerly no other effective therapy. With advances in perioperative techniques, immunosuppressive agents, postoperative care, and a greater understanding of the prognosis of many liver diseases, the results of liver transplantation have improved, with one-year survival figures in excess of 85% for a number of liver diseases. As a result, the procedure is now being offered for a wider range of diseases and to older patients.

The main goals of liver transplantation are to prolong life and improve the quality of life. To achieve these goals, the timing of transplantation is crucial, but in the absence of international or nationally agreed criteria the selection of patients can be difficult and inexact. Ideally, liver transplantation should be performed at a sufficiently late stage of the disease to allow for spontaneous stabilization or recovery, but before the onset of complications of end-stage liver disease that could potentially increase the risk of liver transplantation. In order to optimize the timing of transplantation to increase survival and decrease postoperative morbidity, a number of survival models have been applied to specific liver diseases, and these will be discussed in subsequent sections.

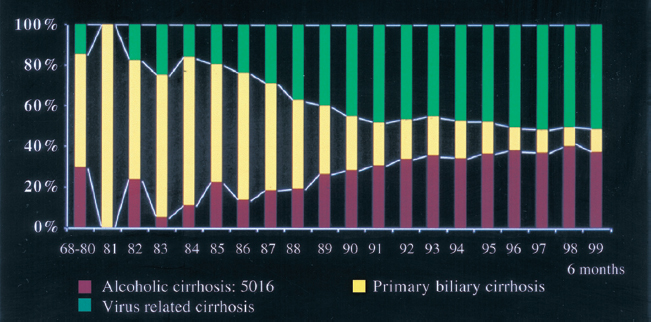

The indications for liver transplantation broadly fall into four main categories: advanced chronic liver disease, acute liver failure, malignancy, and inherited metabolic disorders (Table 7.1). End-stage chronic liver disease accounts for approximately 70 % of all liver transplant activity in Europe and America, but the indications for transplantation have changed over the past ten years, with alcohol-related and viral-related cirrhosis presenting an expanding indication (Fig. 7.1). In the setting of donor shortages and constriction in healthcare budgets, the timing of transplantation becomes even more important.

Summary point:

Summary point:

- The results of liver transplantation have improved, with one-year survival figures in excess of 85% for a number of liver diseases

- Liver transplantation should be performed at a sufficiently late stage of the disease to allow for

- spontaneous stabilization or recovery but before the onset of complications of end-stage liver disease that could potentially increase the risk of liver transplantation

- End-stage chronic liver disease accounts for approximately 70% of all liver transplants in Europe and America

| Chronic liver disease: Primary biliary cirrhosis Primary sclerosing cholangitis Secondary biliary cirrhosis Alcohol Autoimmune hepatitis Viral hepatitis (HCV, HBV, HDV) Budd-Chiari syndrome Metabolic: Wilson disease Hemochromatosis? Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency Familial hypercholesterolemia Familial amyloid polyneuropathy Primary hyperoxaluria Cystic fibrosis Neoplastic: Hepatocellular carcinoma Apudomas Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma Acute liver failure: Drugs/toxins Viral (HAV, HBV) Wilson disease Congenital: Polycystic disease Caroli disease |

HAV, HBV, HBC, HBD, hepatitis A, B, C, and D viruses

Chronic Liver Diseases

Primary Biliary Cirrhosis

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a chronic progressive cholestatic disease characterized by inflammatory destruction of the interlobular bile ducts, affecting predominantly females between 40 and 60 years. The disease is thought to be autoimmune in nature and is serologically characterized by raised IgM titers in association with positive antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA). Radiology has no role to play in the diagnosis or management of PBC until the onset of complications relating to portal hypertension. The disease progresses through three phases: an asymptomatic phase with normal serum bilirubin, lasting up to 20 years, a symptomatic phase marked by pruritus, jaundice, and fatigue, and a third phase characterized by severe jaundice and complications of portal hypertension. Treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is the most commonly used therapy. It reduces cholestasis but its effects on survival are less certain, although some studies suggest a delay in the need for transplantation.1 In contrast to most other liver diseases that require transplantation, the natural history of PBC is well characterized and this facilitates the timing of transplantation. A number of prognostic models have been developed to determine independent risk factors to estimate survival and therefore facilitate patient selection. The most widely used model was developed at the Mayo Clinic2 and identified five independent variables which indicated poor prognosis: age, serum albumin, serum bilirubin, prothrombin time (PT), and edema. The European model identified serum bilirubin and albumin, the presence of ascites, history of gastrointestinal bleeding, and age as independent variables indicating poor prognosis. The most useful variable, common to several prognostic models, is the serum bilirubin,3 and the major indication for transplantation for PBC is a serum bilirubin concentration greater than 6.0 mg/dl (102 μmol/l). At this level of jaundice, the median survival is 25 months, which falls to 17 months when the bilirubin rises above 10 mg/dl (170 μmol/l). Other indications for liver transplantation are listed in Table 7.2.

These models have also been used to assess the efficacy of the transplant procedure. Using the Mayo model, estimated survival of patients who underwent transplantation was superior to the simulated survival of these patients if they had been managed conservatively without transplantation, and the benefit was greatest in patients with the highest risk scores. The five-year survival for PBC following transplantation is 70-80%, and the risk of recurrence at five years seems to be less than 10%.4

| Serum bilirubin 6 mg/dl (170μmol/l)a Refractory ascites Recurring encephalopathy Deteriorating synthetic function (serum albumin < 30g/l, unrelated to active infection) Recurrent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis Recurrent bacterial cholangitisb Hepatopulmonary syndrome Poor quality of life (intractable pruritus, extreme fatigue) Hepatic osteodystrophya,b |

aPrimary biliary cirrhosis

bPrimary sclerosing cholangitis

Summary point:

Summary point:

- Radiology has no role to play in the diagnosis or management of PBC until the onset of complications relating to portal hypertension

- Five independent variables indicate poor prognosis in PBC: age, serum albumin, serum bilirubin, prothrombin time, and edema

- The five-year survival for PBC following transplantation is 70-80%, and the risk of recurrence at five years seems to be less than 10%

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic progressive obliterative process involving the intra- and extrahepatic biliary tree, which ultimately leads to cirrhosis. The etiology of the disease is unknown, but immunologic mechanisms, genetic predisposition, and bacterial and viral infections have all been postulated.5 It occurs predominantly in younger men (mean age at diagnosis 39 years), and is commonly associated with inflammatory bowel disease (more than 75% of cases). Median survival from time of diagnosis is 11.9 years.6 Many patients are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis and the disease progresses insidiously, marked by periods of jaundice and pruritus associated with bacterial cholangitis secondary to stricture formation. Other symptoms relate to chronic cholestasis and portal hypertension. A major concern in PSC patients is the risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma, and long-term studies indicate that 8-30% of patients develop this malignancy over 10 years. Most centers consider cholangiocarcinoma to be a contraindication to liver transplantation.

Several models have been developed on the basis of clinical variables in which a survival risk score can be calculated and translated into a survival function for estimating survival for individual patients with PSC. In the Mayo model, age, serum bilirubin level, hemoglobin, presence or absence of inflammatory bowel disease, and histologic stage were identified as independent predictors of survival. As with PBC, this model indicates that liver transplantation significantly improves the survival rate at all risk stratifications compared with simulated survival in the absence of transplantation.7 Five-year survival rates between 73% and 85% have been reported following transplantation for PSC, based on studies from three transplant centers. However, the major challenge for clinicians is selecting the appropriate time for transplantation, before the onset of significant muscle loss and the development of cholangiocarcinoma. Latent cholangiocarcinoma remains a risk in PSC as its progression is usually silent, and despite routine ultrasound and computed tomographic scanning prior to transplantation, 10% of PSC patients have an unsuspected tumor at surgery. In patients where tumors are suspected despite negative computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) imaging, positron emission tomography (PET) may have a role to play.

Summary point:

Summary point:

- In PSC the risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma is 8-30% over 10 years; most centers consider cholangiocarcinoma to be a contraindication to liver transplantation

- Five-year survival rates of 73-85% have been reported following liver transplantation for PSC

- Latent cholangiocarcinoma is found in 10% of PSC patients at surgery

Alcohol-Related Liver Disease

Alcohol is one of the most significant causes of liver disease in the Western world. While the relationship between alcohol intake and the development of alcohol-related cirrhosis is not simply one of dose-related toxicity, there is a clear relationship between overall alcohol consumption and death from cirrhosis. Recent estimates indicate that the risk of developing cirrhosis with a consumption of 28-41 units per week is 3-4 % at 12 years. This risk increases to 6-7% when more than 42 units are consumed per week.8

An increasing number of patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis are now undergoing transplantation (Fig. 7.1), and alcohol-related disease is the second commonest indication for transplantation in both Europe and America. Long-term survival following transplantation is similar to that for cirrhosis of other causes.9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree