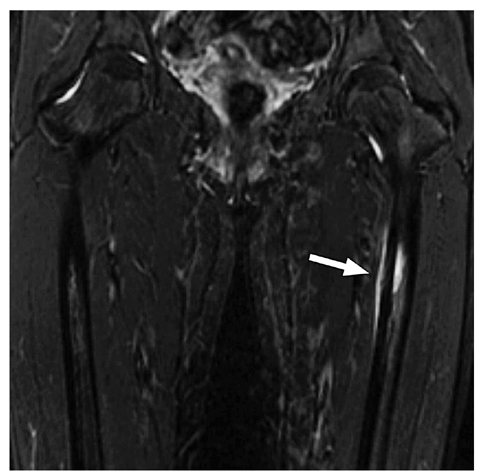

Fig. 1

Stress fractures of the superior pubic rami (arrows) on coronal STIR image of the pelvis in a 15-year-old gymnast

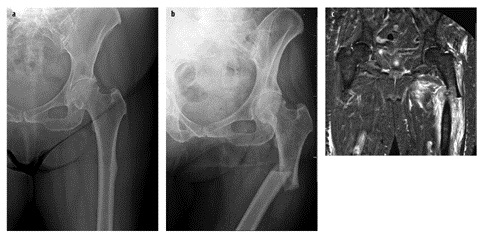

Fig. 2 a–c

Insufficiency fracture of the proximal femur in an 80-year-old woman on bisphosphonate therapy. a Initial radiograph shows thickening of the lateral cortex. b Radiograph 1 week later showing a displaced fracture. c Coronal STIR image showing fracture with hemorrhage

On radiographs, bony stress injuries initially may be invisible, although if the injury occurs in an area with periosteal covering, a faint periosteal reaction may be visible. In the early stage, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will show a curvilinear subcortical rim of edema. As the injury becomes more established, radiographs or computed tomography (CT) show a sclerotic line extending from the cortex into the medullary bone, perpendicular to the major trabecular lines of stress. MRI shows a low signal line corresponding to the sclerotic line (representing trabecular reparative callus) surrounded by marrow edema [1–6].

Common locations for stress fracture in young adults include the pubic rami and femoral neck. Stress fractures can also develop in the proximal femoral shaft related to adductor insertion avulsive stress, also known as „thigh splints” (Fig. 3) [4a].

Fig. 3

Thigh splints. Coronal STIR image of the femur showing periostitis and subcortical bone marrow edema (arrow)

Stress fractures occasionally occur in the subchondral bone of the femoral head [5, 6]. The associated hyperemia results in calcium resorption and can result in appearance of osteopenia on radiographs and CT. Because of the radiographic appearance this entity was formerly referred to as „transient osteoporosis of the hip”. It is seen on MRI as intense bone marrow edema within the femoral head extending into the intertrochanteric region. A subchondral crescent of low signal is seen which represents the fracture line (Fig. 4). The MRI appearance is similar to that of avascular necrosis, but the latter entity generally shows increased bone density on radiographs and CT.

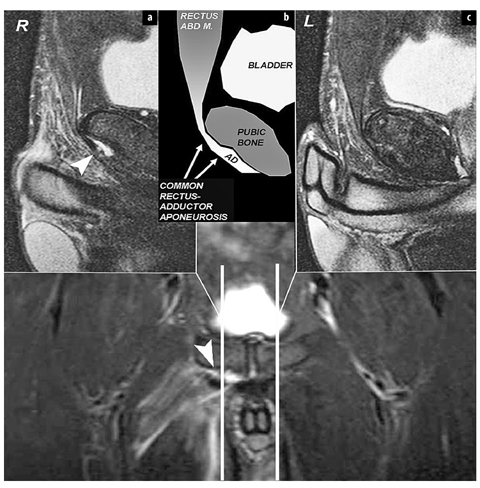

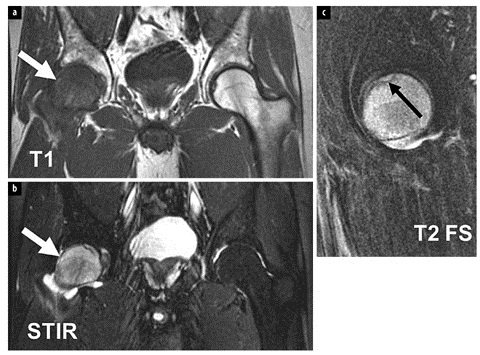

Fig. 4 a–c

Subchondral stress fracture of the femoral head. Coronal T1 (a) and STIR (b) images show diffuse edema of the femoral head (white arrows). Sagittal T2-weighted fat-suppressed image of the hip (c) shows the low signal fracture line (black arrow)

Muscle Strain/Tendon Avulsion

Muscle strain is extremely common in athletes. A variety of muscles can be injured, the pattern depending on the specific movement or mechanism involved. Most muscle strains are diagnosed clinically and treated with physical therapy. For more significant injuries or those that do not improve with rest and time, MRI may be obtained. Ultrasound can be used for a targeted exam whereas MRI provides a global assessment of the injury pattern [7]. Strains are graded by MRI on a scale from 1 to 3. Grade 1 strain is a minor injury, exhibiting mild edema without disruption of fibers. Grade 2 strain is synonymous with a partial muscle tear, where more soft tissue edema is observed along with discontinuity of some fibers; there may be fascial edema as well, and the disrupted fibers may retract along the central tendon complex arising from the myotendinous junction, resulting in a low signal center with surrounding edema at the injury site that is characteristic of a muscle injury. Grade 3 strain is the same as a complete muscle tear with complete discontinuity. With this injury there is extensive soft tissue edema and often hematoma [7–12].

Direct muscle injury (e.g., from traumatic impact) generally occurs in large muscle groups and is centered at the muscle belly; the mid thigh is a common location (Fig. 5). Muscle damage related to indirect injury (e.g., eccentric contraction where the muscle is contracting as it is forced to stretch) is far more prevalent and most commonly occurs at the myotendinous junction [13–15].

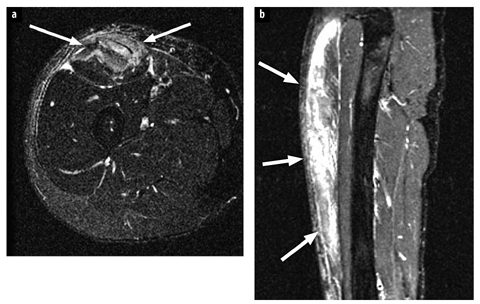

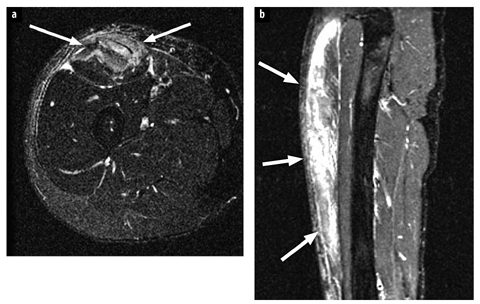

Fig. 5 a, b

Muscle direct injury: quadriceps tear in an 18-year-old man presenting with a painful lump at the anterior thigh after a football game. a Axial T2- weighted fat-suppressed magnetic resonance image shows edema at the muscle belly of the rectus femoris (arrows) representing a partial tear from direct injury. b Sagittal STIR image of the thigh shows extensive edema along the muscle (arrows)

Avulsion fractures occur around the pelvis after acute trauma, but in adolescents stress-related apophyseal injuries can occur (Fig. 6) [16–18]. These are common at the sartorius muscle origin at the anterior-superior iliac spine, at the rectus femoris origin at the anterior-inferior iliac spine and at the hamstring origin at the ischial spine. Older patients are prone to avulsions at the greater trochanter (insertion site of the gluteus medius/minimus and obturator externus). These injuries can be diagnosed on radiographs. If confirmation is necessary, MRI will show edema at the junction indicating underlying pathology.

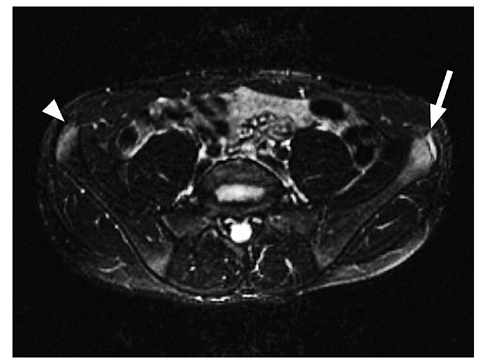

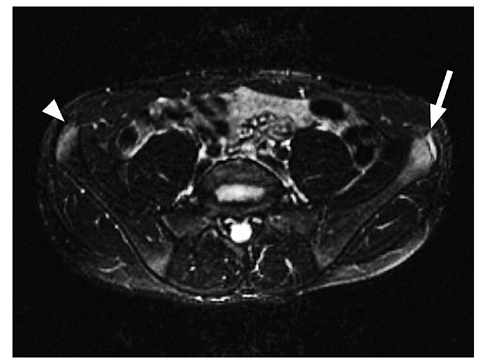

Fig. 6

Apophysitis. Axial T2-weighted fat-suppressed magnetic resonance image shows edema at the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) growth center, at the origin of the sartorius muscle bilaterally (more pronounced on the left, arrow, compared with the right, arrowhead) in this 16-year-old male athlete with chronic pain at the ASIS during activity

Groin Pain and Athletic Pubalgia (Previously Known as „Sports Hernia”)

A key part of the anterior pelvic anatomy that forms the fulcrum for many of the forces is the pubic symphysis (Fig. 7). The muscles that attach to the fulcrum play a major role in stability. One can think in terms of there being four sets of forces and their counterforces that interact with the symphysis fulcrum. For convenience, we think of these forces as residing in three different compartments. The anterior compartment consists mainly of the abdominal muscles with some complex interdigitations composed of fibers from the thighs and medial and posterior pelvis. The posterior compartment primarily encompasses the hamstrings, a portion of the adductor magnus, and several key nerves and an artery. The medial compartment is composed of the most important thigh components, which include the gracilis, the three adductors and the obturator externus.

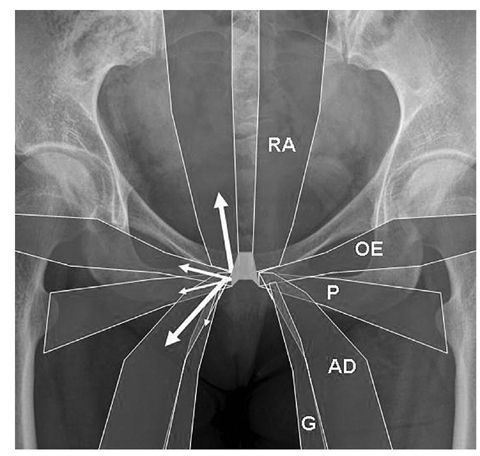

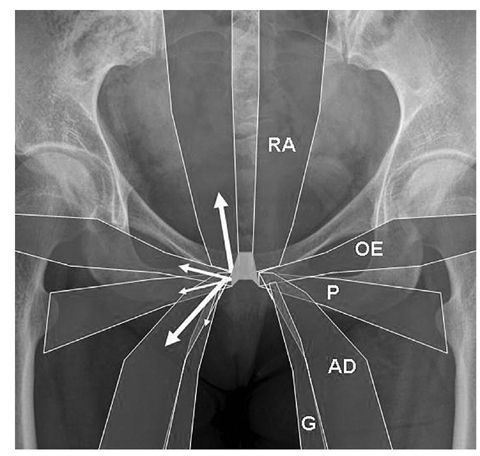

Fig. 7

Diagram showing anatomy of the muscle groups attaching to the pubis. RA rectus abdominis, OE obturator externus, P pectineus, AD adductors, G gracilis. Arrows show force vectors upon the pubis resulting from muscle action (for color reproduction see p 302)

Clinical Presentation

Most commonly individuals who present with athletic pubalgia are males (approximately 10:1 males to females), and typically young and athletic, ranging from high-performance to recreational sports. The injuries occur in the most athletically stressed, hence the fittest of athletes.

Participants of sports involving pivoting and/or contact are especially susceptible (i.e., hockey, American football, baseball, rugby and soccer). Patients present with pain anywhere from the pubic symphysis to the hip, and it may not be clear regarding anatomic origin of the symptoms. Pain and tenderness is often referred to the external inguinal ring, leading to previous misconception that the pathology was related to a hernia in this location, which may at times still be the case.

Imaging findings

Radiographs are generally noncontributory. MRI and ultrasound are the primary modalities used for diagnosis.

The pubic symphysis is marginated by a thick capsule and supporting ligaments, which are normally black on all sequences. The normal symphyseal joint contains a fibrocartilage disc extending in sagittal orientation through the joint which then attaches to the capsule. The rectus abdominis extends down the midline of the abdomen and over the anterior capsule of the pubic symphysis, where it inserts into to the common adductor origin, thereby creating a rectus-adductor aponeurosis. This aponeurosis appears black on all sequences and is tightly attached to the anterior pubis; no fluid should extend from the symphysis into the capsule or aponeurosis („cleft” sign). Nor should fluid extend between the aponeurosis and pubis (aponeurotic separation). The common adductor origin (composed of the pectineus and adductor longus, magnus and brevis) is incorporated into the aponeurosis inferiorly [19–22]. In order to diagnose injuries to the aponeurosis a small field-of-view specialized MRI protocol (available at www.bone.tju.edu) of the pubic symphysis is recommended. Injury patterns involving the pubic symphysis include acute osteitis pubis (seen as diffuse bone marrow edema around the joint), subchondral stress fracture (with a low signal line in the marrow adjacent to the symphysis with surrounding edema) or osteoarthritis (spurs, sclerosis). This injury pattern may be initiated by disruption of the joint capsule and resultant instability of the articulation. With injury to the rectusadductor aponeurosis, this common attachment can „peel off” the capsule of the pubic symphysis and cause severe pain and tenderness over the inguinal ring with limited leg adduction (this is why the incorrect term of „sports hernia” was originally applied). Alternatively the common adductor tendon can tear or avulse and retract. With these lesions MRI provides optimal global evaluation, with fluid seen under or within the aponeurosis (Fig. 8) [20–22]. There is a variable degree of associated adductor muscle strain (usually involving the adductor longus). Ultrasound can also be used, showing focal hypoechogenicity at the adductor origin (Fig. 9).