Fig. 5.1

Digital subtraction angiography. A mask image (a) is obtained, contrast medium administered (b) and a subtracted image (c) produced to highlight (in this case) the superficial femoral artery

Indications

It can be difficult and potentially not without risk to transfer a critically ill patient out of the ICU into the imaging suite. However, there are situations where angiography not only offers a superior diagnostic tool but can facilitate life-saving interventions.

Identification and Treatment of Arterial Hemorrhage

Many of the interventional procedures performed on critically ill patients relate to identifying areas of active bleeding. It is important to appreciate that unless the patient is actively bleeding at the time of angiogram, it is very difficult to identify an abnormal area. The cardinal angiographic findings that suggest recent or active bleeding are contrast extravasation, pseudoaneurysm formation or abnormal “cut-off” of a vessel, which abruptly terminates in a non-anatomical fashion. From the angiographer’s point of view, timely transfer at the time of suspected hemorrhage is preferable. Having said that, it is possible to identify bleeding points in the abdomen with blood loss of as low as 0.5–1 ml/min. Once a bleeding point is found, it may be possible to treat it by embolizing the feeding artery (Fig. 5.2a–d). A variety of embolic agents including liquids, glues, foams, particles, coils and plugs are available with varying properties and indications. Angiography is commonly employed for bleeding complications within the lungs, the GI tract or in the case of pelvic or visceral hemorrhage. It is important to realize that angiography is only one of a number of available diagnostic options and other imaging modalities such as CT angiography (CTA) may be more appropriate in the first instance. In some situations, non-radiological investigations such as endoscopy may be indicated before an invasive imaging test.

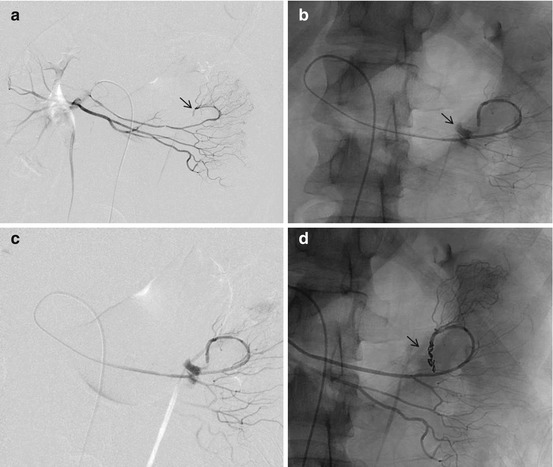

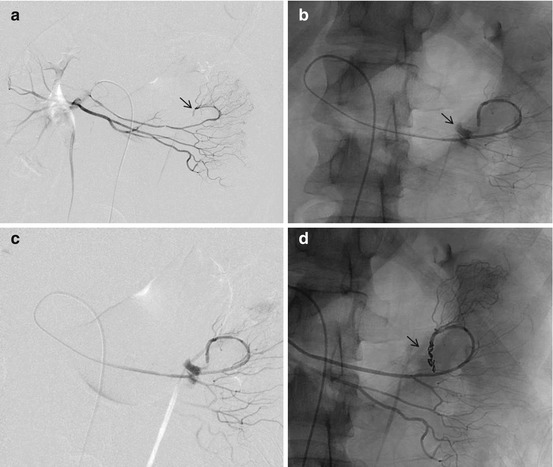

Fig. 5.2

Unstable trauma patient. Initial angiogram (a) from the proximal superior mesenteric artery (SMA) shows abnormal cutoff of a peripheral branch (arrow). Following super-selective catheterisation of the peripheral branch with a microcatheter, unsubtracted and subtracted (b, c) angiograms demonstrate contrast extravasation (arrow) in keeping with active arterial bleeding. This was embolised (d) using multiple microcoils (arrow) with a good embolic result

Nonarterial Hemorrhage

Control of variceal bleeding and portal hypertension may be achieved by means of insertion of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS procedure) to reduce portal venous pressure. Such procedures are technically challenging and may also require varix embolisation as part of the procedure.

Non-hemorrhage Control Procedures

These procedures include insertion and removal of IVC filters to prevent pulmonary emboli, nephrostomy insertion in patients with obstructed kidneys and difficult intravascular access procedures in patients where commonly used vessels are no longer patent. In addition to those the intensivist is likely to encounter patients who have undergone major endovascular procedures such as endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR) as well as those who have undergone neurological interventions such as carotid artery stenting and more recently, catheter directed intra-arterial thrombolysis for acute stroke.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree