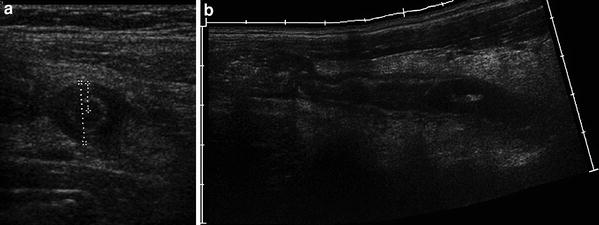

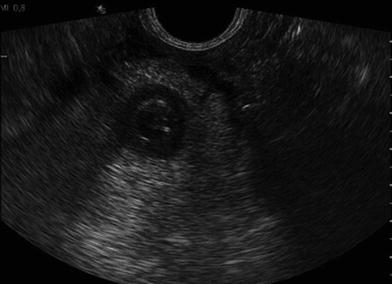

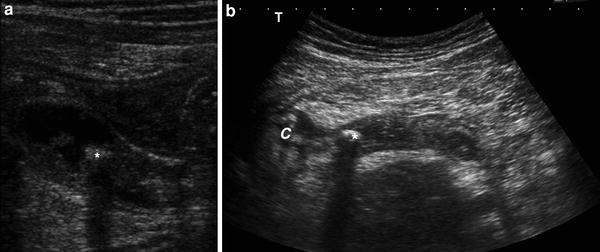

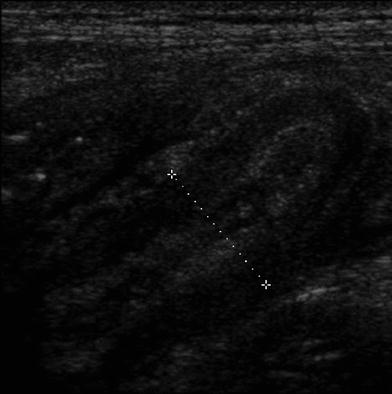

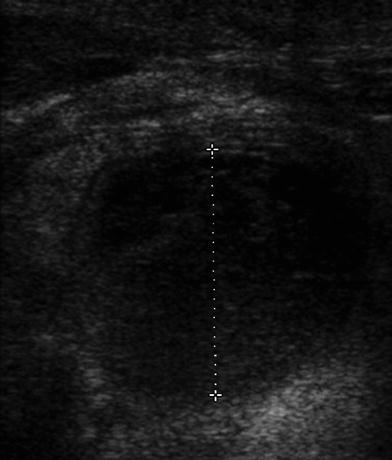

Fig. 1

Normal appendix. a Transverse section b longitudinal section c longitudinal section with a variable amount of air within the tip (asterisk)

Frequently, a high-resolution transducer is used to visualise the appendix during graded compression. In many cases, the appendiceal region can be seen with transabdominal 7.5 MHz transducers. The use of colour or power Doppler may be useful; however, the use of colour Doppler methods is not mandatory.

Ultrasound contrast media have been used for the detection of hypervascularisation (INCESU et al. 2004). Harmonic imaging today is the standard technique in the abdomen. The main advantage is the higher signal-to-noise ratio, but the depth of penetration is lower with this technique. Recently, elastography has also been used in diagnosing of acute appendicitis (Kapoor et al. 2010); however, its exact role has to be established (Table 1).

Table 1

Sonographic signs of acute appendicitis

Missing compressibility (Puylaert 1986a) |

Missing gas in the appendix (Rettenbacher et al. 2000) |

Hypervascularisation of the appendix in colour Doppler (Fig. 4) |

Moderately enlarged lymph nodes. |

Pain directly above the appendix, with obstruction (Puylaert 1986a) |

Faecolith in the appendix, with obstruction (Fig. 5) |

Localised effusion |

In difficult to scan patients and in women, also a transrectal or transvaginal approach may visualise appendiceal region and appendicitis (Figs. 2−6).

Fig. 2

Acute appendicitis. a In transverse section the appendix is round and measures 12 mm in diameter. b Longitudinal panoramic section

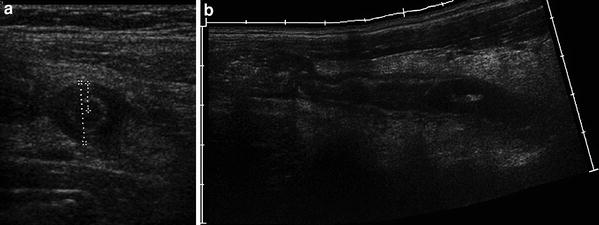

Fig. 3

a Transverse section in appendicitis. The appendix is enlarged and reveals echogenic alteration of the surrounding fat. b Longitudinal sonographic section of a blind ending tubular structure in the right lower quadrant. Acute appendicitis was found operatively. The appendix is dilated up to 13 mm in transverse diameter. The wall of the inflamed appendix is thickened too

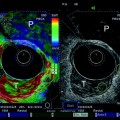

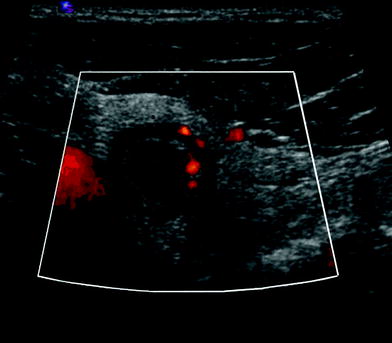

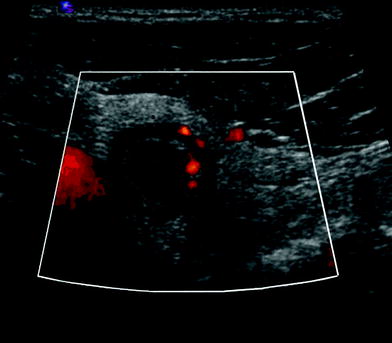

Fig. 4

Transverse section in appendicitis with hyperaemia and thickened wall surrounded by echogenic, hyperemic fat

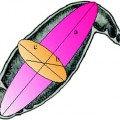

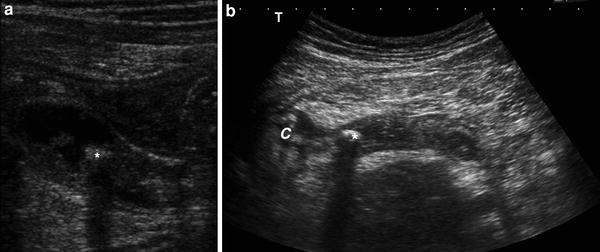

Fig. 5

a Obstructed appendix with faecoliths (astrerisk) and inflammatory content. b Longitudinal sonographic section in a thickened and dilated appendix. Faecoliths (astrerisk) is visualised in the proximal part of the appendix. The cecal pole (arrows) shows a concomitant inflammation. The surrounding fat is more echogenic due to edema

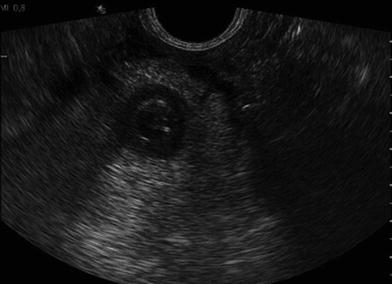

Fig. 6

Transrectal sonography displaying acute appendicitis with echogenic fat reaction

If severe complications, such as significant perforation (Fig. 7) or abscess formation (Fig. 8), are present, the appendix often cannot be visualised as the origin of the inflammation. In these cases, CT should be performed in order to completely delineate the inflammation and to visualise a safe path for a transabdominal drainage; however, the drainage can be performed under US real time guidance.

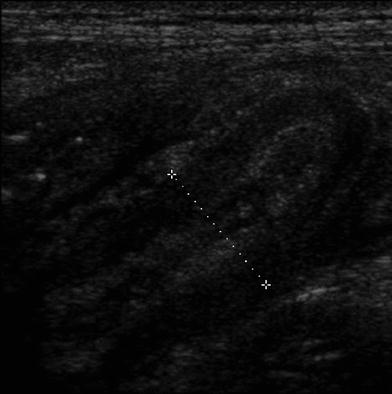

Fig. 7

Longitudinal section of an acute perforated appendicitis

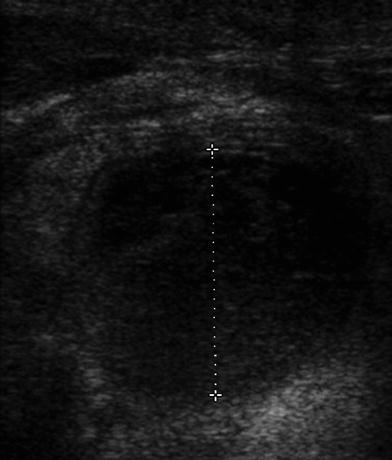

Fig. 8

Perithyplitic abscess. The appendix can not be displayed anymore

The accuracy of sonography in diagnosing appendicitis varies between 70 and 95 % depending on the study (Chan et al. 2005; Kessler et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2005; Puylaert 1986a; Rettenbacher et al. 2002; van Breda Vriesman et al. 2003). In the present author’s opinion, accuracies over 90 % can be achieved if sonography is performed by an experienced team (Gritzmann et al. 2002).

It is generally accepted that, sonography should be performed in clinically questionable cases, in order to reduce the high rate of false-negative appendectomies; however, in clinically highly suspicious cases the incidence of acute appendicitis was only about 70 %; therefore, it was advocated that sonography be performed in all cases with pain in the right lower quadrant (Rettenbacher et al. 2002). In rare cases the appendix may show an inflammed diverticel (Macheiner et al. 1999).

An acute appendicitis can be excluded if the normal appendix can be completely displayed and/or a differential diagnosis that explains the clinical findings can be found.

3.2 Computed Tomography

In the United States computed tomography (CT) is the preferred method in the evaluation of acute appendicitis (Rao et al. 1997); however, CT provides significant radiation doses to the patients.

CT can be performed only in the region of the painful right lower quadrant if it is preceded by sonography. This is a way to reduce radiation in young patients. Modern multi-detector scanners can visualise the abdomen at low doses using modes with a high spatial resolution. The main advantage of CT is that the operator dependency is lower than with sonography. Furthermore, the normal appendix can be seen in a higher percentage than with sonography. In European institutions, CT is often used as a problem-solving investigation if sonography fails to give a clear diagnosis (van Breda Vriesman et al. 2003). In the United States CT is more frequently used as primary investigation (Frush and Frush 2009; Gaitini et al. 2008).

After oral application of water-soluble contrast media, perithyplitic abscesses or bowel loop abscesses are usually better delineated by CT.

3.3 Magnetic Resonance

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also used to diagnose acute appendicitis (Hörmann et al. 1998; Birchard et al. 2005; Tkacz et al. 2009; Leeuwenburgh et al. 2010). With fast sequences the lower abdomen can be imaged within seconds (for instance HASTE sequence). The prompt availability is a prerequisite for diagnosing acute appendicitis. The accuracy is reported to be comparable to that of CT (Hörmann et al. 1998); however, its relative high costs enable only MRI as a problem-solving investigation.

In the future this may change; however, up to now, MRI is not a primary standard imaging in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

4 Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis can be divided into intestinal (Table 2), gynaecological, urological and diseases of other compartments (mainly abdominal wall, psoas muscle, gallbladder, pancreas).

Table 2

Intestinal differential diagnoses of acute appendicitis

Infectious ileocolitis |

Lymphadenitis mesenterica |

Invagination |

Volvulus |

Right-sided diverticulitis, sigmoid diverticulitis |

Appendix diverticulitis, perforation or inflammation of diverticula of the small bowel |

Meckel’s diverticulum (complications) |

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis |

Tumour (perforated) |

Ileocaecal tuberculosis |

Ischaemia of the small bowel |

Appendagitis, omental necrosis |

4.1 Intestinal Differential Diagnosis

Most often infectious ileocoecitis is found (Puylaert 1986b; Tarantino et al. 2003). Sonographically the cecum and/or the terminal ileum are moderately thickened. The cecum shows hyperhaustration. Most often enlarged painful regional lymph nodes are found. The most frequent microbes are Yersinia, Campylobacter or Salmonella (Puylaert et al. 1988). Appendix can be reactively enlarged by these diseases.

When examining children, in the event of a painful lower quadrant, invagination of the small bowel has to be considered. The sonographic picture is typical. A double-layer intussusception can be visualised. With adults, tumours causing invagination have to be excluded. Furthermore, complications of a Meckel’s diverticulum (inflammation, bleeding) have to be taken into account (Baldisserotto et al. 2003). Another differential diagnosis when examining children is a volvulus (Patino and Munden 2004). In this condition, the mesenteric vessels show a whirlpool sign.

In adults, diverticulitis of the ascending colon or cecum is an important conservatively managed disease (Wada et al. 1990). Also diverticulitis of the sigmoid colon can be right sided or projected on the right side (Hollerweger et al. 2001

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree