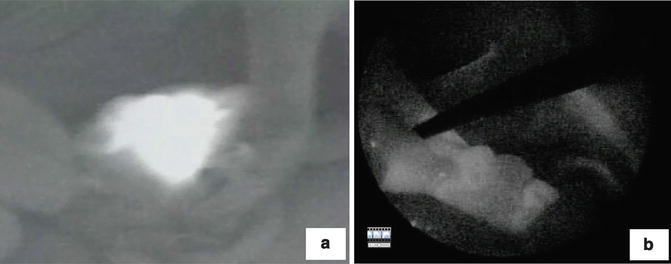

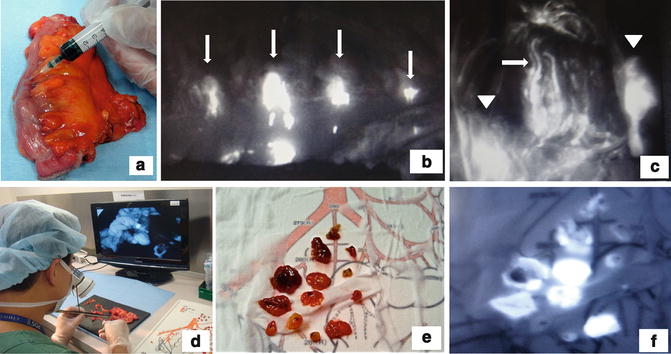

Fig. 21.1

Sentinel lymph node mapping. (a) ICG solution was injected intraoperatively into the four points of the subserosa around the tumor. (b) Lymph node (arrowhead) and lymph duct (arrow) were emitted

Discussion

Here, we describe a way to detect SLNs of colorectal cancer using IFI. The methods for detecting SLNs can be categorized as dye methods, radioisotope (RI) methods, ICG fluorescence (IF) methods, and combination methods according to tracer. Dye methods offer only poor tissue contrast, which makes detection of SLN in deep, dark anatomical regions [18, 19] such as the lower rectum extremely difficult. RI methods are available without sighting of the lymphatic flow. However, they are expensive and there are limitations as to which institutions can use them [18, 19]. While IF methods require sighting of lymphatic flow, the visibility of the IF method is superior to the visibility of dye method, and the IF methods cost less than RI methods [2, 20, 21]. Hirche et al. reported that ICG guidance has been shown not to be influenced by the body mass index (BMI) or lymphatic invasion, whereas conventional methods are [21].

In this study, lymphatic vessels and SLN were clearly visualized by their bright fluorescence in real time.

As for colorectal cancer, the significance of SLNB itself is still controversial. But it may help reduce invasive operations and optimize lymph node dissection. SLNB using IFI is a promising tool that deserves further clinical exploration.

Tattooing of Tumor Location by ICG Fluorescence Imaging

Background

In early colorectal cancer, the precise detection of tumor location is often difficult due to unclear palpation with the fingers in colorectal surgery, particularly laparoscopic surgery. Therefore, endoscopic colorectal tattooing is frequently performed because it is a simple and economic technique to identify tumor localization [22]. Tattooing with India ink has been used since 1975, as first reported by Ponsky and King [23]. However, tattooing with India ink has been associated with complications, i.e., colonic abscess formation [13], peritonitis [13], inflammatory pseudotumor [14], and adhesion ileus [15]. Some institutions have reported the utility and safety of tattooing with IFI [24, 25]. Here, we describe our experience tattooing with IFI.

Materials and Methods

ICG solution was made by dissolving 25 mg of powdered ICG in 10 ml of sterile physiologic saline, and 0.2 ml volumes were endoscopically injected into 4–5 points of the submucosal areas around tumors in colon cancers. During subsequent laparotomy, the colon was first observed with the naked eye, and during subsequent laparotomy, IFI was observed by PDE (photodynamic emission) camera or by a prototype of fluorescence endoscopy for the detection of marking areas during laparoscopic operation.

Results

IFI showed the tumor localization clearly and accurately by bright fluorescence in all patients with open surgery (Fig. 21.2a) or laparoscopic surgery (Fig. 21.2b). The regions tattooed with ICG were hardly green at all in color.

Fig. 21.2

Confirmation of tattooing of tumor location by ICG fluorescence imaging. (a) Open surgery. (b) Laparoscopic surgery

There were no complications of LED-induced fluorescence, and no inflammatory signs were noted on the HE-stained slides for the identified injection sites in the resected specimens.

Discussion

Small cancer lesions in the colon can be difficult to palpate, and with lack of tactile sensation, it is essential to accurately localize them preoperatively. India ink tattooing is widely used for tumor localization [22]; however, this tattooing procedure is not yet standardized, and several complications associated with this technique such as colonic abscess formation [13], peritonitis [13], inflammatory pseudotumor [14], and adhesion ileus [15] have been reported.

As for the interval between injection and operation, it was reported that tattooing with ICG should be performed up to 5–8 days prior [24, 25]. However, tattooing with ICG seemed to disappear earlier than tattooing with India ink [25].

The regions tattooed with ICG were hardly green at all. ICG concentrations should be high enough to be recognized as green [24]. However, the ICG concentrations can be reduced for recognition of fluorescence by LED-induced fluorescence. Therefore, in spite of the lower ICG concentrations, tumor localization was clearly and accurately visualized. This may be related to the safety of tattooing with IFI.

In this study, we could observe the tumor localization clearly and accurately. Moreover, there were no complications of LED-induced fluorescence and no inflammatory signs. The IFI tattooing method proved effective for tumor localization. Fine and clear tattooing points could be obtained, and the potential complications caused by the tattooing with India ink could be avoided by IFI technique.

LN Harvest from Resected Specimens by Using ICG Fluorescence Imaging

Background

The staging of lymph node factor is determined by the number of metastatic LNs rather than the stationary location of metastatic lymph nodes. Therefore, the number of harvested LNs is very significant for the exact staging of colorectal cancer. Here, we suggest one of the useful ways of harvesting LNs using IFI.

Materials and Methods

To harvest LNs, we injected 0.2 ml ICG solution made by dissolving 25 mg of powdered ICG in 10 ml of sterile physiologic saline at each of the four points around tumors intraoperatively or postoperatively (Fig. 21.3a–c). First, we harvested LNs by the conventional procedure, and then we reexamined whether there were LNs left behind by a PDE camera, which enabled us to detect the IFI absorbed by the LNs (second harvest) (Fig. 21.3d–f). Furthermore, we searched for IFI-labeled LNs in paraffin-embedded specimens (Fig. 21.4a–c). This study enrolled a total of 31 patients with colorectal cancer, including 24 with colon cancer and 7 with rectal cancer.

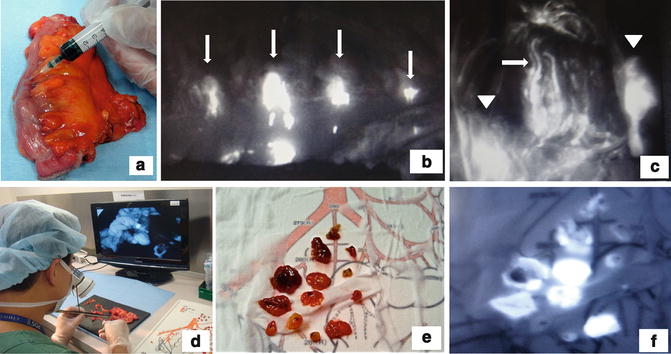

Fig. 21.3

Lymph node harvested from resected specimens using ICG fluorescence imaging. (a) Ex vivo ICG injection. (b) ICG injection point is emitted (arrow). (c) Lymph node (arrowhead) and lymph duct (arrow) were emitted. (d) Second harvest with ICG fluorescence imaging. (e) Harvested lymph nodes. (f) ICG fluorescence imaging of harvested lymph nodes

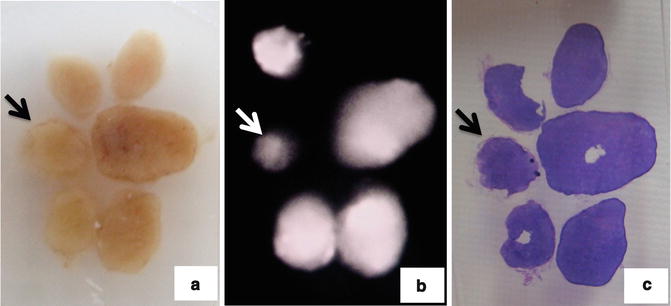

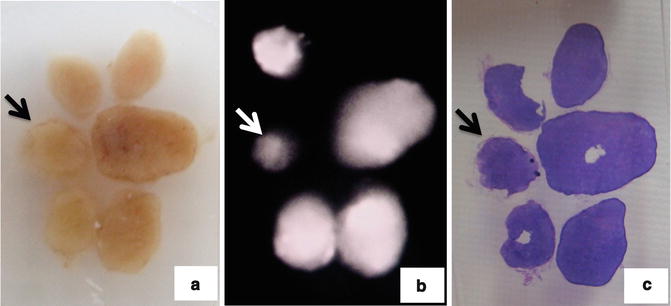

Fig. 21.4

Observation of paraffin block. Arrow shows metastatic lymph node. (a) Paraffin block of lymph nodes. (b) ICG fluorescence imaging of paraffin block of lymph nodes. (c) Hematoxylin-eosin staining of lymph nodes

Results

We could observe lymph ducts (LDs) and nodes (LNs) by ICG injection into resected specimens (Fig. 21.3c). However, it was hard to observe IFI in cases with advanced cancer or ink tattooing. We observed IFI in harvested LNs in all 31 colorectal cancers (Fig. 21.3e). In 23 of the 31 cases (74 %), we could observe the LDs and LNs by IF ex vivo lymph node harvest procedures (Table 21.1). We tried to detect additional lymph nodes in 7 of 23 cases observed by IF ex vivo lymph node harvest procedures. In four of these seven cases (57 %) in which additional lymph nodes could be detected, we could find additional lymph nodes left in situ. Furthermore, in one of these four cases (25 %) at least one of the additionally harvested LNs was metastatic (Fig. 21.3e, f and 21.4a–c).

Table 21.1

ICG fluorescence imaging observed by ICG ex vivo injection (n = 31)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree