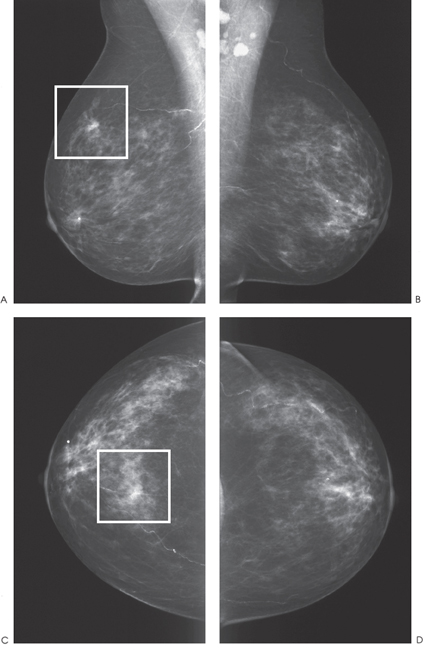

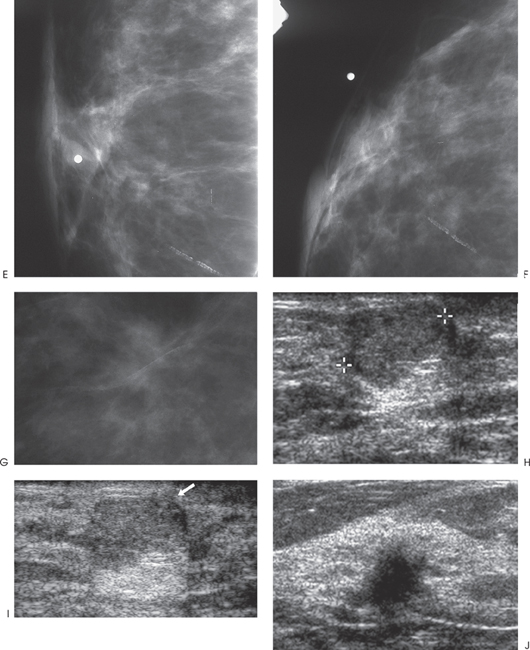

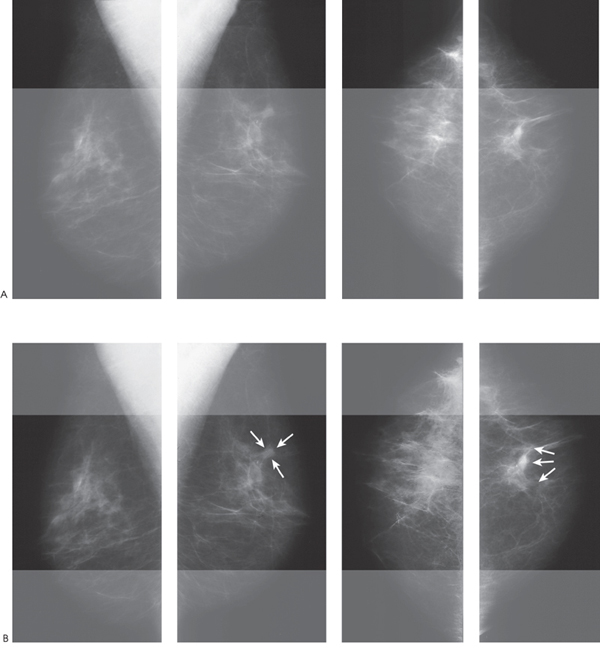

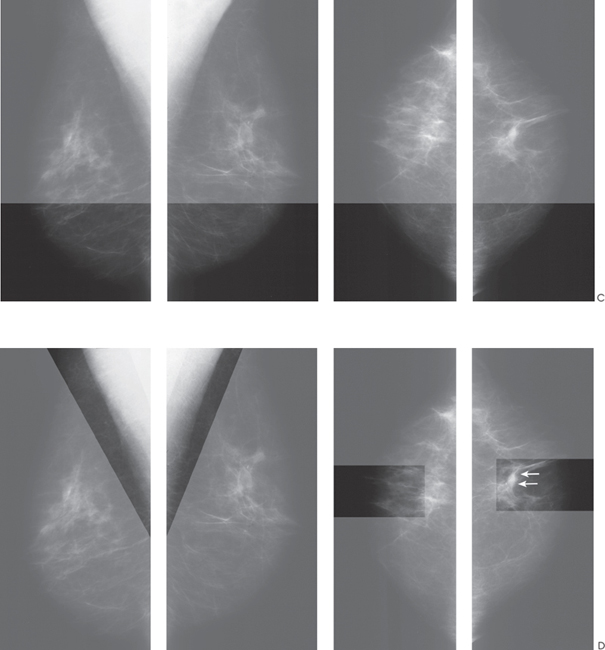

Chapter 1 General Overview There are three critical factors that lead to identifying mammographic abnormalities: production of high-quality images, perception of a lesion, and characterization of the finding. A team of people is needed to produce high-quality mammograms. The radiologist and the technologist should constantly be evaluating images for film contrast, exposure parameters, patient position, and image processing. Furthermore, a radiation physicist should work with the technologists to monitor equipment performance. Perception of mammographic abnormality is the first step in identifying a breast malignancy. Perception is aided by a systematic review of the mammographic examination. Consistent systematic review of the mammogram is critical in avoiding perceptual errors. Tabar and Dean’s Teaching Atlas of Mammography has an excellent explanation of a horizontal and vertical masking technique that facilitates identification of abnormal mammographic asymmetries. Masking entails physically covering portions of the film so that only small corresponding regions of the two breasts are visible. In a busy practice, this technique may not be practical, but one can develop the ability to visually mask by focusing on a small area of the breast and comparing it to the equivalent area on the contralateral side. My personal method involves this latter technique. I visually horizontally mask all breast views and then perform a second focused review of the axilla and the subareolar regions (Fig. 1–1). During the review of the mammographic examination, one may identify asymmetries or calcifications. One should classify the asymmetry as a density or architectural distortion. The densities should be further analyzed and subdivided into either masses or asymmetric densities. Using the following methods, the breast imager then analyzes the lesion and assigns an assessment category according to the American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS). These assessment categories are the following: • Category 0—Need additional imaging evaluation. This evaluation may include additional mammographic views (e.g., spot compression) or other imaging modalities (e.g., ultrasound). • Category 1—Negative. The breasts are normal. • Category 2—Benign finding. The mammogram is normal, but there is a finding that the interpreter wishes to describe. • Category 3—Probably benign finding. Short-interval follow-up suggested. The finding has a high probability of being benign and is not expected to change in appearance. In this book, I generally assume that the patient will be reimaged about 6 months after this assessment is made. • Category 4—Suspicious abnormality. Biopsy should be considered. The radiologist has enough concern about the lesion that biopsy is being recommended. • Category 5—Highly suggestive of malignancy. Appropriate action should be taken. Patterns of Mammographic Abnormality After finding an asymmetry, the breast imager should classify the finding into one of four patterns: mass, asymmetric density, calcifications, and architectural distortion. Masses If a density is identified, then the radiologist should first clarify if the density is a mass or a focal asymmetric density. A mass is a density that has a consistent shape when imaged at different angles and with different patient positions. If one concludes that the lesion is a mass, then one should determine whether the shape of the mass is circumscribed or irregular. Circumscribed masses are round, oval, or lobulated (see Section 3). Circumscribed masses are commonly benign. Only 1.4% of well-defined circumscribed masses are malignant. As there are many benign lesions in this category, diagnostic evaluation should be directed to excluding many of these benign lesions from being biopsied. The first step is to analyze the density of the mass. If the mass contains fat, then the abnormality is benign (Category 2) and does not require biopsy. If the mass has a density equal or greater than parenchyma, then further examination is necessary. The next step is to examine the margins of the mass. If the margins are sharp or obscured by the surrounding parenchyma, then the mass should be examined sonographically. If the mass clearly has ill-defined or spiculated borders, then biopsy is indicated (Category 4 or Category 5). This biopsy may be performed sonographically as almost all of these lesions are sonographically visible, particularly if they are larger than 4 to 5 mm. Figure 1–1. (A–C). Systematic method to review mammograms. Horizontal examination: Initially, one should focus on a small region in the superior section of the right film and then compare it to the comparable left side. One should then proceed inferiorly in the mammogram and continue this process. In this case, there is trabecular thickening and architectural distortion at the 12:00 position of the left breast (arrows). This lesion is an infiltrating ductal carcinoma. (D). Systematic method to review mammograms (axillary and subareolar examination). After the horizontal examination, one should study the axillary and subareolar regions of each breast and compare each area to the contralateral side. The axillary region is important because the upper outer quadrant contains the highest percentage of breast cancers. Extra attention to the subareolar region is worthwhile as this area exhibits a complex architecture consisting of numerous ductal lines. Subareolar architectural distortion is commonly difficult to identify. As noted earlier, circumscribed mammographic masses that have well-defined or obscured margins should be examined sonographically. Of these masses, sonographically identified cysts are obviously benign (Category 2). If the mass is well-defined and uniformly hyperechoic to fat, it is probably benign (Category 3). The mass is also probably benign (Category 3) if it has all of the following characteristics: (1) shape: round, oval, or one or two large lobulations; (2) margin: well defined with hyperechoic thin capsule; (3) echogenicity: uniformly hypoechoic; (4) size: 1 cm or smaller. If the margin is extremely well defined but does not have a hyperechoic capsule, I also assess it as probably benign (Category 3). To characterize whether a margin is well defined one must have high-quality, high-resolution, and high-frequency (≥10 MHz) equipment. Furthermore, the entire margin must be well defined and clearly visible (Fig. 1–2). Finally, there should not be any other associated abnormality such as sonographic architectural distortion. In this situation, I am also assuming that I have seen the patient only once and there is no evidence of growth. If the lesion has been identified on earlier imaging exams and has grown in size or if it is larger than 1 cm, then I will recommend biopsy (Category 4). The reason for biopsing large or growing well-defined lesions is that some of the masses in this category will be malignant. As long as a malignancy is small, it has a good prognosis since the probability of metastasis is low. However, to have a good prognosis, it is best for the patient to be Stage 1 (primary tumor smaller than 2 cm) at the time of diagnosis. Shortinterval follow-up of a small (< 1 cm) well-circumscribed mass that has a low probability of malignancy is a reasonable method to avoid unnecessary biopsies. If the mass has any other sonographic characteristics, then it is Category 4 or Category 5. Examples of these lesions include: (1) solid masses within cysts, (2) masses that have any other shape or that are microlobulated, (3) lesions that exhibit heterogeneous echogenicity or that present as a focal area of intense shadowing, (4) tumors with either completely or partially ill-defined margins, (5) masses associated with other sonographic abnormalities such as architectural distortion. Masses with microlobulations or other shapes that cannot be classified as circumscribed should be considered irregular in shape (see Section 4). Although benign etiologies may produce an irregular mammographic mass, all mammographically irregular masses should be pathologically examined unless the lesion is a benign scar. Scars resulting from previous surgery may appear similar to malignancies. A careful patient history with a map of the scar is necessary to correlate the mammographic abnormality with the clinical information. If this information is insufficient, previous films commonly document either stability or reduction of the lesion density and size. Occasionally, sonography may be necessary to differentiate scar from malignancy. In these cases, sonography may confidently exclude malignancy if only hyperechoic architectural distortion is present without mass. Furthermore, sonographically scars change in appearance with different transducer positions. Even if there is a wide area of severe shadowing in one view, the orthogonal view will demonstrate only a thin line of architectural distortion characteristic of scar. Because scar attenuates high-frequency more than low-frequency ultrasound, commonly low-frequency sonography is more effective in characterizing scar (see Case 178, Section 9). Besides scar, other benign entities produce irregular masses. These lesions include fat necrosis, sclerosing adenosis, focal fibrosis, hematoma, abscess, and benign neoplasms such as fibroadenomas or papillary lesions. However, unless the patient has a clinical history or symptoms suggesting recent trauma, surgery, or infection, these lesions cannot be differentiated from malignancy and should be biopsied. When clinical information suggests that a hematoma or abscess may be responsible for the mammographic abnormality, then sonography is useful to identify these processes.

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine