Stroke in children is relatively rare. Advances in the clinical recognition and radiographic diagnosis of ischemic stroke have increased the frequency of the diagnosis in infants and children and have raised the need for immediate therapy. A vast amount of data has recently become available through basic research and neuroimaging techniques shedding new light on the chain of events that occur in ischemic stroke in animal models and in the adult population. Whether this new information can also be applied to the pediatric population remains to be seen, but it is likely that the active management of children with acute ischemic stroke in the near future will include brain protection, brain reperfusion, and prevention measures.

Stroke in children is relatively rare. Isolated cases of stroke in the pediatric population were documented in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, but no significant epidemiologic data became available until the late 1970s . Most reports in the past focused on the underlying pathologies that can occur in children presenting with a stroke, and few dealt with the outcome of stroke in the various age groups and how treatment might affect them. In fact, the treatment of stroke in children has mainly been geared toward management of the underlying causes.

Advances in the clinical recognition and radiographic diagnosis of ischemic stroke have increased the frequency of the diagnosis in infants and children and have raised the need for immediate therapy including reperfusion therapy and brain protection. Few reports have dealt with the active treatment of acute stroke in children. No randomized control trials have been done other than studies in children with sickle cell disease and adults, which are not directly applicable to the general pediatric population with a stroke. The lack of published clinical trials and of experience in treating a large number of cases has resulted in a significant challenge for clinicians.

A vast amount of data has recently become available through basic research and neuroimaging techniques shedding new light on the chain of events that occur in ischemic stroke in animal models and in the adult population. Whether this new information can also be applied to the pediatric population remains to be seen, but it is likely that the active management of children with acute ischemic stroke in the near future will include brain protection, brain reperfusion, and prevention measures.

Epidemiology

Vascular occlusive disease is increasingly seen in infants and children. Two population-based studies in the United States have indicated that the incidence rate of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke is 2.52 cases per 100,000 population per year and the rate of ischemic stroke 1.2 cases per 100,000 population per year . The incidence varies in children with different ethnic backgrounds. Based on prospectively collected data from 1985 to 1993 in France, the incidence of ischemic stroke was 8 cases per 100,000 population and the incidence of hemorrhagic stroke 5 cases per 100,000 population . These data were for children less than 16 years of age. Sixty-one percent of the cases were ischemic strokes and 39% were hemorrhagic. In the Canadian Pediatric Ischemic Stroke Registry, 820 children were identified with ischemic stroke aged from birth to 18 years, yielding an incidence of 3.3 cases per 100,000 children per year. Arterial ischemic stroke (AIS) constituted 80% of the cases . A study performed in the North American population based on telephone consultation service showed that 64% of cases were ischemic stroke and 36% sinovenous thrombosis. That study also demonstrated a mean age of 6.2 years. The most affected age group comprised persons from birth to 3 years of age, and neonates comprised 16% of patients. The rate of male gender was 54% .

Clinical presentation

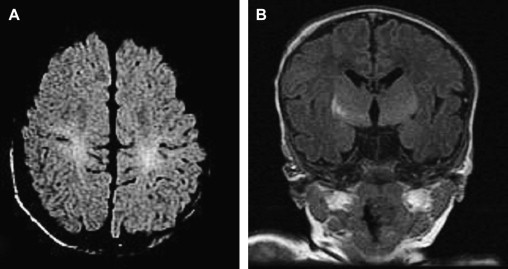

The clinical presentation of ischemic stroke in the pediatric population is age related. Neonates with AIS tend to present with convulsions and lethargy. They rarely, if ever, present with an appreciable focal neurologic deficit in the acute phase. The neurologic deficit slowly becomes apparent over the next few months to year ( Fig. 1 ) . Delayed presentation of a neurologic deficit such as decreased hand use occurred in 18 of 22 patients with presumed pre- or perinatal AIS. All of these patients were considered neurologically normal until at least 2 months of age. All 22 patients had some weakness on longer follow-up, and 12 developed permanent signs of speech, cognitive, or behavioral deficits. Five had persistent seizures . The late symptoms can cause delayed diagnosis in this age group.

Infants tend to present with pathologically early hand preference as a sign of previous stroke. The actual time of onset of the stroke often cannot be determined . In fact, the evolution is often similar to that in patients whose strokes are identified during the perinatal period. Sometimes, older infants and toddlers present with abrupt onset of hemiparesis, facial droop, or difficulty in moving one of the extremities . The clinical presentation not infrequently consists of fever, convulsion, and coma.

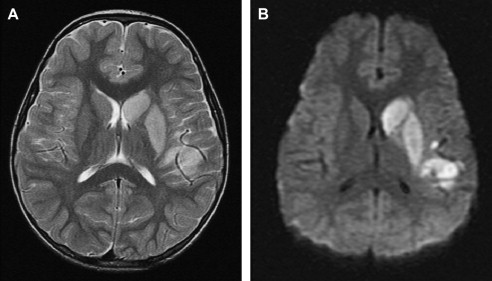

Presentation of stroke in later childhood is typically an acute neurologic deficit, usually hemiparesis ( Fig. 2 ). Subtle signs such as speech or visual disturbances, headache, or sensory deficits can also be part of the presentation. Seizures can accompany the stroke in 50% of cases . In a study recently published in Turkey, 79 patients presented with a stroke. Fifty-seven had acute ischemic stroke; the mean age of that group was 29.6 months. Thirty-nine of the patients presented with hemiparesis. Eleven patients had seizures, and five had altered mental status .

Clinical presentation

The clinical presentation of ischemic stroke in the pediatric population is age related. Neonates with AIS tend to present with convulsions and lethargy. They rarely, if ever, present with an appreciable focal neurologic deficit in the acute phase. The neurologic deficit slowly becomes apparent over the next few months to year ( Fig. 1 ) . Delayed presentation of a neurologic deficit such as decreased hand use occurred in 18 of 22 patients with presumed pre- or perinatal AIS. All of these patients were considered neurologically normal until at least 2 months of age. All 22 patients had some weakness on longer follow-up, and 12 developed permanent signs of speech, cognitive, or behavioral deficits. Five had persistent seizures . The late symptoms can cause delayed diagnosis in this age group.

Infants tend to present with pathologically early hand preference as a sign of previous stroke. The actual time of onset of the stroke often cannot be determined . In fact, the evolution is often similar to that in patients whose strokes are identified during the perinatal period. Sometimes, older infants and toddlers present with abrupt onset of hemiparesis, facial droop, or difficulty in moving one of the extremities . The clinical presentation not infrequently consists of fever, convulsion, and coma.

Presentation of stroke in later childhood is typically an acute neurologic deficit, usually hemiparesis ( Fig. 2 ). Subtle signs such as speech or visual disturbances, headache, or sensory deficits can also be part of the presentation. Seizures can accompany the stroke in 50% of cases . In a study recently published in Turkey, 79 patients presented with a stroke. Fifty-seven had acute ischemic stroke; the mean age of that group was 29.6 months. Thirty-nine of the patients presented with hemiparesis. Eleven patients had seizures, and five had altered mental status .

Etiology

The causes of ischemic stroke in children are varied and differ significantly from the underlying causes in adults. In the majority of children (80%), a specific etiologic cause for the stroke can be found. In pediatric AIS, arteriopathies, cardiac disease, and prothrombotic disorders are the most commonly recognized risk factors ( Fig. 3 ).

Different causes will be found according to the geography, including sickle cell disease in North America and infectious causes in India or sub-Saharan countries. Etiologies are sometimes intricate and their mechanisms combined. All children have some sort of infection every 6 months and are exposed daily to more or less benign trauma while playing. Post infectious, post traumatic etiologies are often discussed, such as dissection, concentric proliferation, and emboli. Any combination of these entities can be seen in stroke in children.

The etiologies of AIS in childhood are often multifactorial and different from those in adults, in whom arteriosclerotic disease is the single most common cause. Extensive investigations need to be conducted in children to facilitate understanding the pathogenesis. The following constitute some of the examinations performed to determine the cause of stroke in children:

Blood samples, including a count, serum electrolytes, C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate, coagulation times, and fibrinogen titer

Blood samples for measurement of triglycerides and cholesterol, amino acid chromatography, lactates, protein C, protein S, antithrombin III, and antiphospholipid antibodies

Urine samples for amino acid chromatography and organic acid chromatography

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination for cell count and protein titration, titer of viral antibodies in serum and CSF, or complement and polymerase chain reaction for varicella zoster virus DNA

An echocardiogram, standard electroencephalogram (ECG), prolonged (24-hour) ECG recording, CT, MR imaging, and digital subtraction arteriography

Cardiac disorders

The most common identifiable cause of childhood stroke is congenital heart disease. The most common underlying cardiac conditions are Fallot’s tetralogy and transposition of the great vessels. Emboli from the heart or from the periphery through a right-to-left shunt are significant causes of ischemic stroke in the pediatric population ( Fig. 4 ). Thrombi can form on prosthetic cardiac valves and represent another important cause of cerebral emboli. Stroke can also happen at the time of cardiac procedures (catheterization or surgery) . Kaplan and colleagues reported the rate of AIS after cardiac catheterization to be 1.9 cases per 1000 procedures and the rate after surgery 1.0 cases per 1000 procedures.

Genetic diseases involving the cardiovascular system and causing stroke are rare but should be suspected in certain cases . One example is hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu disease), which can be associated with early stroke (neonatal or infant) secondary to a pulmonary arteriovenous fistula .

Establishing the etiologic cause of an embolic stroke is not based exclusively on transthoracic cardiac ultrasound. Transesophageal ultrasound can be used in young children to reveal a thrombus or a patent foramen ovale with paradoxical emboli. Because artificially induced dysrhythmia represents a risk factor for embolic stroke, Holter monitoring and other studies are required to rule it out. As a rule, the younger the child, the more likely congenital heart disease will be the cause, in particular before the age of 2 years.

Vasculopathy

Fever or evidence of infection is common in children presenting with cerebral infarction. Bacterial or viral meningitis can be responsible for an infectious type of arteritis resulting in stroke in children . Chicken pox occurred in the 12 months before the onset of symptoms in 31% of children (among 70 children) presenting with AIS who were aged 6 months to 10 years in comparison with 9% of the population . Stroke has been described as a rare complication in children infected with HIV, occurring in about 1% of affected children, although autopsy evidence of infection has been documented in 10% to 30% .

Transient cerebral arteriopathy is characterized by a temporary attack on the cerebral arterial wall and accounted for 26% of childhood strokes in Sebire’s series . This arteriopathy is presumed to be secondary to an inflammatory process, possibly triggered by an infectious agent such as varicella zoster virus or bacterial agents ( Fig. 5 ) . One of the most striking features of this arteriopathy is the transient action of the pathologic process. This transient nature has been demonstrated angiographically by repeated examinations showing, often after initial worsening, regression or stabilization of arterial lesions and clinically by long-term follow-up showing a lack of late recurrence. This acute regressive arteriopathy might represent an important part of ischemic strokes in childhood . The angiographic appearance characterized by focal or segmental stenosis and tail-like occlusions does not suggest an embolic or a thrombotic process but is consistent with abnormalities of the arterial wall ( Fig. 6 ). The pathophysiology of such arterial lesions cannot be established on an angiographic basis. The acute and regressive course is consistent with an acute process such as arteritis, dissection, or vasospasm. The lack of anamnestic events (eg, drug absorption, trauma, or meningeal hemorrhage) and the persistence of arterial lesions make the hypothesis of a vasospasm or dissection unlikely.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree