Between 85% and 90% of all neoplasms in the stomach and duodenum are benign. About 50% are mucosal lesions and 50% are submucosal. Most of these benign neoplasms are discovered fortuitously on radiologic or endoscopic studies performed for other reasons. Occasionally, however, tumors that are large or ulcerated may cause abdominal pain or upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. Depending on their histologic features, some benign tumors are also important because of an associated risk of malignancy. Although gastric and duodenal polyps are rarely diagnosed on single-contrast barium studies, the use of double-contrast technique has led to greater detection of these lesions.

Mucosal Lesions

Gastric polyps comprise about 50% of all benign neoplasms in the stomach. Polyps are much less common in the duodenum. In the past, gastric polyps were rarely detected on single-contrast barium studies, with a reported incidence of only 0.01% to 0.05%. However, the routine use of double-contrast technique has dramatically improved our ability to detect gastric polyps, with a reported incidence of 1% to 2% on double-contrast studies. Most are small, innocuous hyperplastic polyps, but some larger lesions are adenomatous polyps capable of undergoing malignant degeneration via an adenoma-carcinoma sequence similar to that in the colon. The need for endoscopic biopsy and removal of these polyps is directly related to their size and appearance. Radiologists therefore have an important role in the detection of gastric polyps and in subsequent decisions about patient management.

Hyperplastic Polyp

Hyperplastic polyps are the most common benign epithelial neoplasms in the stomach, comprising 75% to 90% of all gastric polyps. Because hyperplastic polyps are not premalignant, they must be differentiated from adenomatous polyps, which have a known risk of malignant degeneration. Although histologic specimens are required for a definitive diagnosis, hyperplastic polyps have such a characteristic appearance on double-contrast barium studies that they can usually be differentiated from adenomatous polyps without need for endoscopy.

Pathology

Hyperplastic polyps consist histologically of elongated, branching, cystically dilated glandular structures. They usually appear grossly as small, sessile nodules with a smooth, dome-shaped contour. Because these polyps have a self-limited growth pattern, most are smaller than 1 cm. Hyperplastic polyps almost never undergo malignant degeneration. Nevertheless, affected individuals are at increased risk for harboring separate, coexisting gastric carcinomas. In various series, 8% to 28% of patients with hyperplastic polyps in the stomach have been found to have synchronous gastric carcinomas. This association is probably related to the presence of underlying atrophic gastritis, which predisposes to the development of polyps and cancer. Hyperplastic polyps are therefore important because of the increased risk of these patients developing gastric carcinoma.

Fundic gland polyps appear to be a variant of hyperplastic polyps arising within fundic gland mucosa in the fundus and body of the stomach. They consist histologically of cystically dilated, hyperplastic fundic glands that have no malignant potential. Because affected individuals almost always have multiple (up to 50) gastric polyps, this entity has been called fundic gland polyposis. Fundic gland polyps are typically found in middle-aged women. Fundic gland polyposis can occur as an isolated condition in the stomach but also develops in about 40% of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome (FAPS; see Chapter 61 ). Thus, colonoscopy is often recommended for patients with fundic gland polyposis to determine whether they have FAPS and whether colonic surveillance is warranted.

Clinical Findings

Most hyperplastic polyps are small (<1 cm in diameter), innocuous lesions detected as incidental findings on radiologic or endoscopic examinations. Rarely, polyps that have a friable or ulcerated surface may cause low-grade upper GI bleeding, and pedunculated polyps in the gastric antrum may prolapse through the pylorus, causing intermittent symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction.

Radiographic Findings

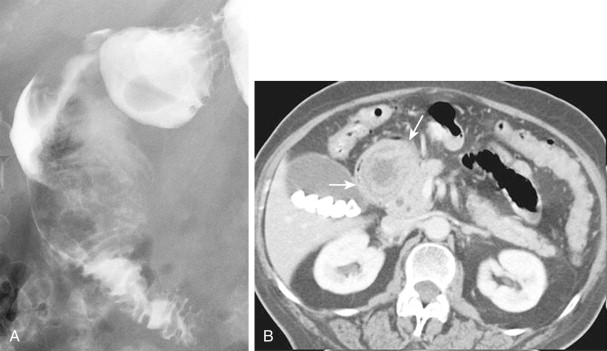

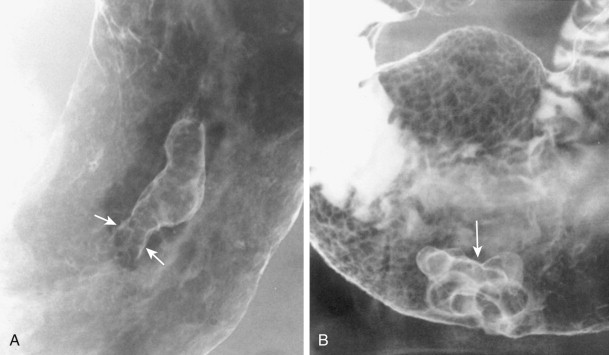

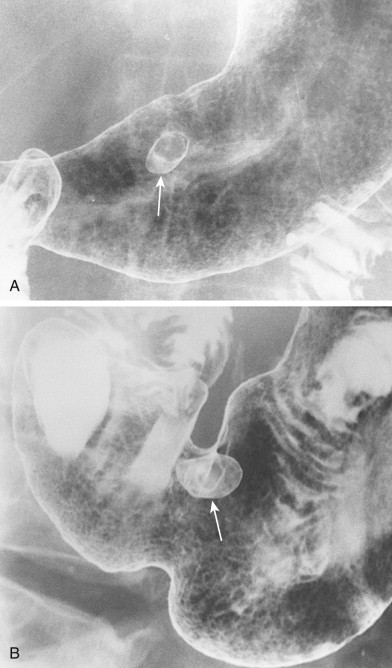

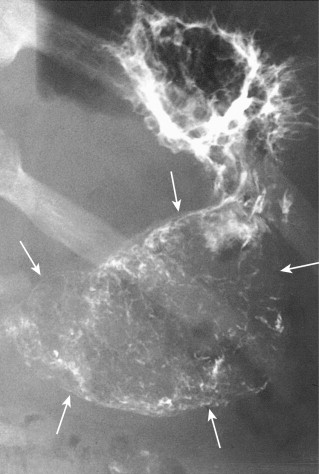

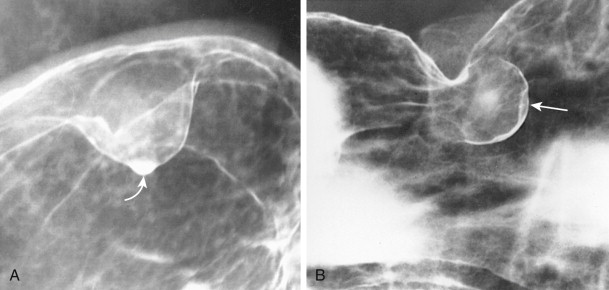

Most hyperplastic polyps in the stomach appear on double-contrast studies as smooth, sessile, round or ovoid nodules, ranging from 5 to 10 mm in diameter. They tend to occur as multiple lesions in the gastric fundus or body ( Fig. 31-1 ). When multiple polyps are present, they also tend to be similar in size.

Hyperplastic polyps on the dependent surface of the stomach (i.e., the posterior wall) typically appear on double-contrast studies as smooth, round filling defects in the barium pool, whereas polyps on the nondependent surface (i.e., the anterior wall) appear as ring shadows that are etched in white because of trapping of barium between the edge of the polyp and adjacent mucosa (see Fig. 31-1A ). A small hanging droplet of barium, or stalactite, on a nondependent or anterior wall polyp can be mistaken en face for a central area of ulceration (see Fig. 31-1B ), but this droplet of barium is seen as a transient finding at fluoroscopy. Occasionally, one or more stalactites may be present as the only sign of hyperplastic polyps on the anterior wall. In such cases, careful examination of the area with prone compression views should demonstrate the underlying polyps responsible for this phenomenon.

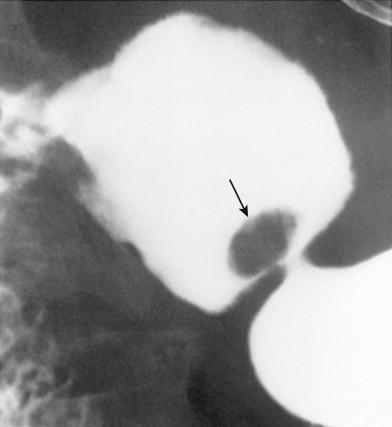

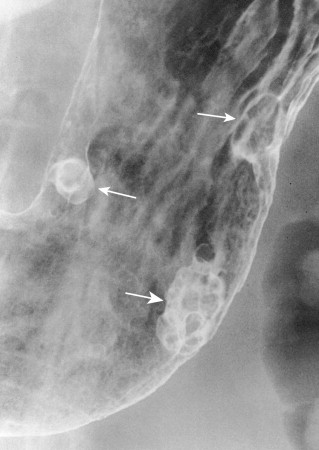

Although most hyperplastic polyps are smaller than 1 cm, some atypical polyps can be as large as 2 to 6 cm, appearing as lobulated or pedunculated lesions ( Fig. 31-2 ). A giant hyperplastic polyp or conglomerate mass of hyperplastic polyps can occasionally be mistaken for a polypoid gastric carcinoma (see Fig. 31-2B ). Rarely, pedunculated hyperplastic polyps in the antrum may prolapse through the pylorus into the duodenum, causing gastric outlet obstruction ( Fig. 31-3 ).

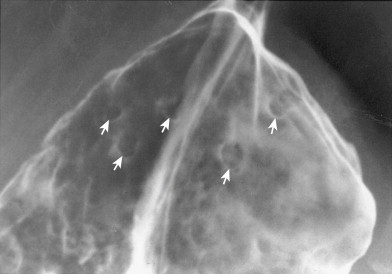

Fundic gland polyps appear on double-contrast examinations as multiple small (<1 cm in diameter), rounded nodules in the gastric fundus or body that are indistinguishable from hyperplastic polyps ( Fig. 31-4 ). In some patients, spontaneous regression of fundic gland polyps has been reported.

Differential Diagnosis

Hyperplastic polyps that appear as ring shadows on double-contrast studies must be differentiated from shallow ulcers on the dependent or posterior gastric wall and from unfilled ulcers on the nondependent or anterior wall. With flow technique, however, shallow ulcers on the dependent wall should fill with barium, whereas ulcers on the nondependent wall should fill with barium on prone compression views. Thus, it is usually possible to differentiate these lesions with a biphasic examination, which includes flow technique and prone compression.

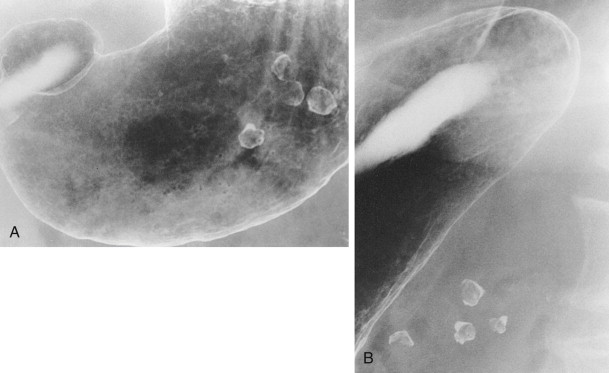

Polyps that appear as ring shadows must also be distinguished from see-through artifacts caused by overlying structures that are calcified (e.g., phleboliths) or partially filled with contrast material (e.g., barium-containing colonic diverticula). Such structures can mimic the appearance of anterior wall polyps on a single view ( Fig. 31-5A ), but their location outside the stomach is readily apparent on images obtained in other projections ( Fig. 31-5B ).

Hyperplastic polyps that are lobulated or are larger than 1 cm in size cannot be distinguished from adenomatous polyps in the stomach. Rarely, giant hyperplastic polyps or a conglomerate mass of hyperplastic polyps can mimic a polypoid gastric carcinoma (see Fig. 31-2B ). Thus, polyps that are unusually large or lobulated should be evaluated by endoscopy and biopsy and, if necessary, resected for a definitive diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for multiple hyperplastic polyps in the stomach includes multiple adenomatous polyps and gastric involvement by one of the polyposis syndromes. However, adenomatous polyps tend to be larger and less numerous and are more lobulated than most hyperplastic polyps. Both types of polyps can occur simultaneously in some patients, but an adenomatous polyp should be suspected if one lesion is disproportionately larger than the others. A generalized polyposis syndrome should be suspected if multiple polyps are also present in the small bowel or colon (see Chapter 61 ).

Treatment

Almost all smooth, sessile polyps smaller than 1 cm are hyperplastic polyps that have no malignant potential. Small, round, or ovoid gastric polyps detected on double-contrast studies should therefore be considered innocuous lesions without need for further investigation or treatment. Endoscopic biopsy or polypectomy should be performed, however, if the polyp is lobulated or pedunculated, larger than 1 cm, or enlarges on follow-up barium studies.

Adenomatous Polyp

Adenomatous polyps constitute less than 20% of all gastric polyps. Nevertheless, these polyps are important because they are capable of undergoing malignant degeneration. Thus, they must be treated more aggressively than hyperplastic polyps in the stomach.

Pathology

Adenomatous polyps are composed of dysplastic epithelium. Depending on the predominant glandular architecture, they may be classified as tubular, villous, or tubulovillous adenomas; the vast majority are tubular or mixed tubulovillous adenomas. Malignant degeneration of these lesions occurs via an adenoma-carcinoma sequence similar to that in the colon. Foci of carcinoma in situ or invasive carcinoma are present in almost 50% of resected adenomatous polyps larger than 2 cm, but malignant changes are rarely found in smaller lesions. As in the colon, the risk of malignant tumor therefore depends primarily on polyp size. Nevertheless, adenocarcinoma is 30 times more common than adenomatous polyps in the stomach, so most gastric cancers are thought to originate de novo and not from preexisting polyps.

Adenomatous polyps are often found in the stomach in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis. Because of the association between atrophic gastritis and gastric carcinoma (see Chapter 32 ), the risk of developing a separate gastric cancer may be greater than the risk of malignant degeneration in an adenomatous polyp. As many as 30% to 40% of patients with adenomatous polyps in the stomach have been found to have gastric carcinomas. Thus, detection of an adenomatous polyp in the stomach should lead to a careful search for other lesions.

Clinical Findings

Because of their larger size, adenomatous polyps in the stomach produce symptoms more frequently than hyperplastic polyps. These patients may present with epigastric pain, bloating, upper GI bleeding or, rarely, symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction.

Radiographic Findings

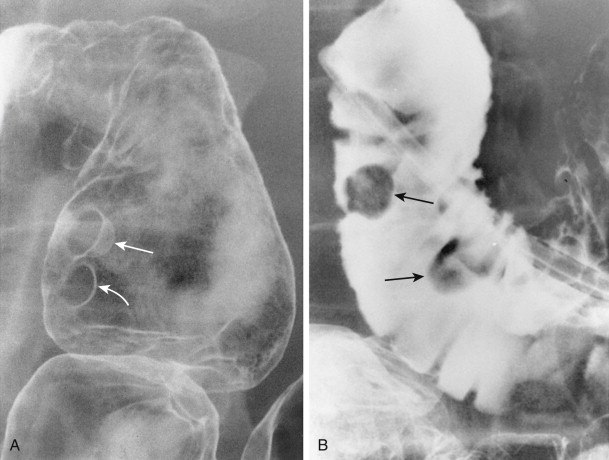

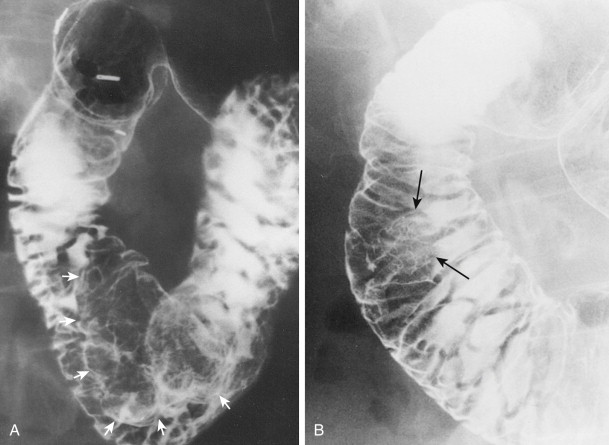

Most adenomatous polyps diagnosed in the stomach on barium studies are larger than 1 cm. They usually occur as solitary lesions, most frequently in the antrum ( Fig. 31-6 ), but multiple adenomatous polyps are sometimes found ( Fig. 31-7 ). The polyps may be sessile or pedunculated, and they tend to be more lobulated than hyperplastic polyps (see Figs. 31-6 and 31-7 ). When the lesions are pedunculated, the stalk may be seen en face as an inner ring shadow overlying the head of the polyp, producing the Mexican hat sign, which is typically found with pedunculated polyps in the colon (see Fig. 31-6B ). Rarely, pedunculated antral polyps may prolapse through the pylorus, causing intermittent gastric outlet obstruction.

As with hyperplastic polyps, lesions on the nondependent or anterior wall may be etched in white on double-contrast views. Occasionally, a hanging droplet of barium (i.e., stalactite) on these nondependent lesions can mimic the appearance of ulceration. However, adenomatous polyps are rarely ulcerated.

Differential Diagnosis

Adenomatous polyps in the stomach that appear as smooth, sessile lesions may be difficult to distinguish on barium studies from hyperplastic polyps. However, most adenomatous polyps are larger than 1 cm and usually occur as solitary lesions, whereas hyperplastic polyps are almost always smaller than 1 cm and are often multiple. Adenomatous polyps that are sessile and have a smooth contour can also be mistaken for benign gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) or other submucosal lesions. Finally, adenomatous polyps that are larger and more lobulated may be indistinguishable from polypoid gastric carcinomas (see Fig. 31-7 ). Adenomatous polyps often harbor one or more foci of carcinoma in situ or invasive carcinoma, so aggressive management of these lesions is required.

Treatment

When a gastric polyp is detected on barium studies, endoscopic biopsy specimens should be obtained if the lesion has features of an adenomatous polyp (i.e., >1 cm, is lobulated or pedunculated, or enlarges on follow-up barium studies). If biopsy specimens confirm the presence of an adenomatous polyp, it should be resected because of the risk of malignant degeneration. Regardless of the endoscopic findings, polyps larger than 2 cm should always be resected because of the even greater likelihood that they are adenomatous and the high risk of malignant tumor in adenomatous polyps of this size. If invasive carcinoma is present in the resected specimen, a wedge resection of the stomach or partial gastrectomy may be required. As in the colon, a much more aggressive approach is therefore warranted in the management of adenomatous polyps than hyperplastic polyps because of the increased cancer risk in these patients.

Duodenal Polyp

Duodenal polyps are much less common than gastric polyps. Hyperplastic polyps, which constitute most gastric polyps, are rarely found in the duodenum. Instead, most duodenal polyps are adenomatous. Because these polyps rarely cause symptoms, they are usually detected as incidental findings on radiologic or endoscopic examinations. Occasionally, however, duodenal polyps may cause low-grade upper GI bleeding or obstructive jaundice.

Radiographic Findings

Duodenal polyps usually appear on barium studies as smooth, sessile lesions in the first or second portion of the duodenum ( Fig. 31-8 ). They tend to be smaller than 2 cm, but giant duodenal polyps have occasionally been described. Most duodenal polyps occur as solitary lesions, but multiple adenomatous, hamartomatous, or inflammatory polyps may be found in the duodenum as part of a diffuse polyposis syndrome (see Chapter 61 ).

Differential Diagnosis

Sessile polyps in the duodenum may be difficult to distinguish on barium studies from benign GISTs, Brunner gland hamartomas, or other submucosal masses, so endoscopy may be required for a definitive diagnosis. Occasionally, antral mucosa or even pedunculated antral polyps that prolapse through the pylorus can be mistaken for polypoid lesions in the duodenum ( Fig. 31-9 ; see also Fig. 31-3 ). However, prolapsed antral mucosa is usually manifested by a characteristic mushroom-shaped defect at the base of the bulb. In other patients, apparent polypoid lesions may result from heaped-up areas of redundant mucosa on the inner aspect of the superior duodenal flexure between the first and second portions of the duodenum ( Fig. 31-10 ). However, these flexural pseudolesions can usually be differentiated from true polyps by their characteristic location and changeable appearance at fluoroscopy.

Villous Tumor

Adenomatous polyps in the stomach and duodenum that contain predominantly villous elements have been called villous adenomas, papillary adenomas, papillomas, or adenomatous papillomas. Because of their high malignant potential, however, the term villous tumors is probably best, because it avoids the erroneous impression that these lesions are always benign.

Pathology

Villous tumors in the stomach and duodenum closely resemble those in the colon, appearing grossly as polypoid masses with numerous frondlike projections. They usually occur as solitary lesions, ranging from 3 to 9 cm in size, but giant villous tumors as large as 15 cm have been reported. Villous tumors rarely cause gastric outlet obstruction because of the soft consistency of these lesions. They are equally distributed in the stomach, but duodenal lesions tend to be located in the descending duodenum near the papilla of Vater.

Villous tumors in the stomach and duodenum are associated with an even higher risk of malignant change than villous tumors in the colon. The risk of malignant tumor is directly related to the size of the lesion. In the stomach, malignant changes are found in 50% of lesions 2 to 4 cm in size and in 80% of lesions larger than 4 cm. Similarly, malignant changes are found in 30% to 60% of villous tumors in the duodenum, with the highest cancer risk in lesions larger than 4 cm. Although villous tumors in the stomach and duodenum have been classified as benign neoplasms in this chapter, for all practical purposes they should be treated as malignant lesions.

Clinical Findings

Most patients with villous tumors in the stomach and duodenum are over 50 years of age. They may present with signs or symptoms of upper GI bleeding, such as melena, guaiac-positive stool, and iron deficiency anemia. Because villous tumors in the duodenum are often located near the papilla of Vater, some patients may develop obstructive jaundice. In contrast to villous tumors in the colon, however, villous tumors in the stomach and duodenum rarely cause diarrhea or electrolyte depletion. Although gastric and duodenal lesions have the same secretory capabilities as those in the colon, reabsorption of fluid and electrolytes in the small and large bowel apparently prevents the development of a diarrheal syndrome.

Villous tumors in the stomach and duodenum should be resected because of the high risk of malignant degeneration. Some benign lesions can be removed by endoscopy, but those harboring invasive cancer usually require surgery.

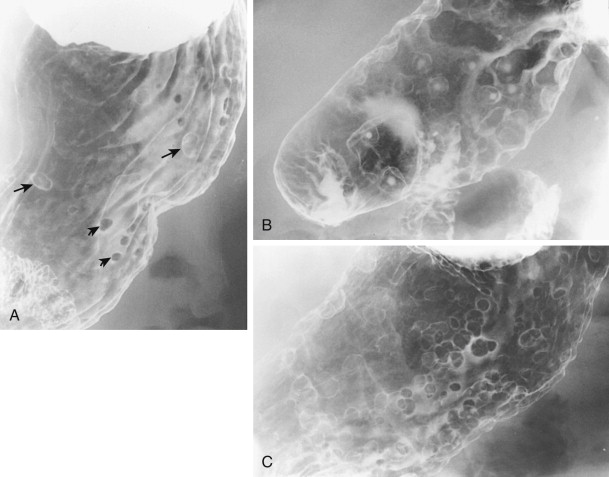

Radiographic Findings

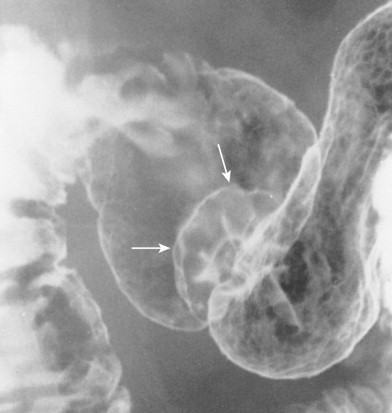

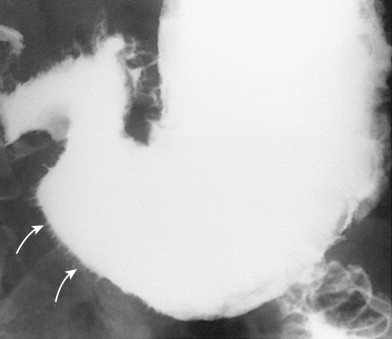

Villous tumors in the stomach and duodenum usually appear on barium studies as polypoid masses, ranging from 2 to 9 cm in size. The lesions often have a reticular or soap bubble appearance with serrated, feathery margins caused by trapping of barium in multiple clefts between the frondlike projections of the tumor ( Figs. 31-11 and 31-12 ). Thus, villous tumors in the stomach and duodenum have the same radiographic features as those in the colon.

Villous tumors in the duodenum tend to be located near the papilla of Vater (see Fig. 31-12 ), but occasionally are found as far proximally as the duodenal bulb. Because these lesions are easily obscured by superimposed mucosal folds, they are best visualized on double-contrast studies with optimal distention of the duodenum. Hypotonic duodenography (after intravenous [IV] administration of 1 mg of glucagon) is a particularly effective technique for effacing the overlying folds, so subtle lesions in the periampullary duodenum are better seen (see Fig. 31-12B ).

Differential Diagnosis

A large gastric bezoar may occasionally produce a soap bubble appearance, mimicking that of a villous tumor in the stomach as a result of barium trapped in the interstices of the bezoar. However, the freely mobile nature of the bezoar with changes in the patient’s position should suggest the correct diagnosis. Carcinoma or lymphoma of the stomach or duodenum may also be manifested by a bulky intraluminal mass, but these lesions rarely produce a soap bubble appearance.

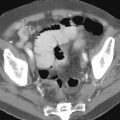

Polyposis Syndromes

With the widespread use of double-contrast radiography and endoscopy, gastroduodenal involvement by the polyposis syndromes has proved to be far more common than previously recognized (see Chapter 61 ). In patients with FAPS, detection of adenomatous polyps in the stomach or duodenum is particularly important because of the malignant potential of these lesions and the increased risk of developing gastric or duodenal carcinoma . Some investigators therefore believe that periodic surveillance of the upper GI tract should be performed on all patients with FAPS. Other polyposis syndromes involving the stomach and duodenum include Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, juvenile polyposis, and Cowden’s disease (see Chapter 61 ). In patients with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, barium studies may reveal distinctive whiskering along the margins of the stomach because of trapping of barium between tiny mucosal excrescences ( Fig. 31-13 ). When accompanied by characteristic ectodermal findings, this appearance should be highly suggestive of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome.

Submucosal Lesions

The terms submucosal and intramural are used interchangeably in this chapter. Nevertheless, it should be recognized that all submucosal lesions are intramural, but not all intramural lesions are submucosal because they can also arise from the muscularis propria or even the subserosa . These mesenchymal lesions constitute about 50% of all benign neoplasms in the stomach or duodenum. Almost 90% are GISTs. Other submucosal lesions include leiomyoblastomas, lipomas, hemangiomas, lymphangiomas, glomus tumors, neural tumors, granular cell tumors, inflammatory fibroid polyps, ectopic pancreatic rests, Brunner gland hamartomas, and duplication cysts. Most benign submucosal tumors are discovered as incidental findings at surgery or autopsy, but lesions that are large or ulcerated may cause abdominal pain or upper GI bleeding. Some mesenchymal tumors are important because of an increased risk of malignancy. Submucosal masses may be difficult to visualize at endoscopy because the overlying mucosa appears normal. As a result, barium studies are particularly helpful for detecting these lesions.

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor

Although GISTs were once thought to represent smooth muscle tumors (leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas), they are now believed to arise from the interstitial cells of Cajal and are characterized by their unique immunohistochemical expression of CD-117, also known as c-kit, a cell surface membrane receptor with tyrosine kinase activity. In one study, almost all submucosal masses previously classified as smooth muscle tumors were found to be GISTs, with the exception of submucosal masses in the esophagus, in which true leiomyomas were far more common. GISTs constitute about 90% of mesenchymal tumors and 40% of all benign tumors in the stomach and duodenum. These lesions are important, not only because they may cause symptoms, but also because a small percentage are found to be malignant.

Pathology

GISTs consist histologically of intersecting bundles of spindle-shaped cells in a characteristic whorling pattern that distinguishes these tumors from normal smooth muscle. Depending on their growth pattern, GISTs may appear grossly as endogastric, exogastric, or so-called dumbbell lesions. About 80% are endogastric lesions that remain intramural but grow toward the lumen. Another 15% are exogastric lesions that grow outward from the stomach toward the peritoneal cavity. The remaining 5% are dumbbell-shaped lesions that have endogastric and exogastric components.

Almost all benign gastric and duodenal GISTs occur as solitary lesions, but multiple tumors are found in 1% to 2% of patients. Most benign GISTs in the stomach and duodenum are smaller than 3 cm, but some patients may have giant lesions as large as 25 cm. As these tumors enlarge, they often outgrow their blood supply, causing central necrosis and ulceration. In various series, ulceration has been documented in 50% to 70% of all gastric GISTs larger than 2 cm.

About 90% of GISTs in the stomach are found to be benign lesions. However, it is often difficult to differentiate benign from malignant GISTs by histopathologic criteria. The most commonly accepted microscopic index of malignancy is the degree of mitotic activity in the tumor. Nevertheless, mitotic activity may be increased in only a portion of a malignant GIST, so random biopsy specimens or frozen sections may erroneously suggest a benign lesion. Thus, a definitive diagnosis of malignant tumor ultimately depends on the tumor’s biologic behavior and the demonstration of invasive growth beyond the stomach via direct extension, lymphatic spread, or hematogenous metastases (see Chapter 33 ).

Clinical Findings

Benign gastric and duodenal GISTs occur with about equal frequency in men and women. Affected individuals are usually over 50 years of age. Most patients with lesions smaller than 3 cm are asymptomatic . As these tumors enlarge, ulceration of the lesion may cause epigastric pain or upper GI bleeding, manifested by hematemesis, melena, guaiac-positive stool, or iron deficiency anemia. Occasionally, pedunculated GISTs in the gastric antrum may cause nausea and vomiting because of intermittent gastric outlet obstruction.

Radiographic Findings

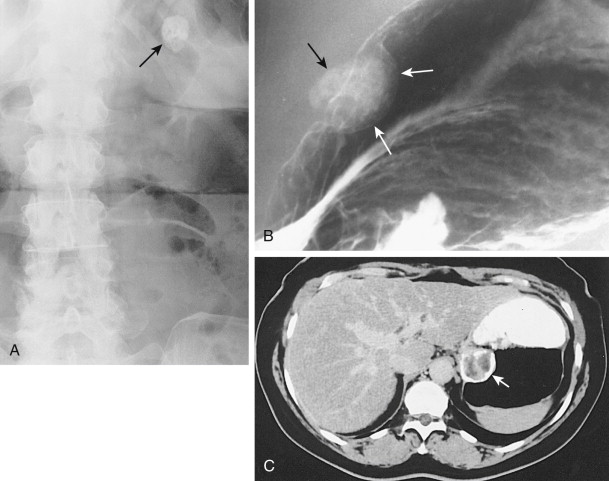

Most benign GISTs are not diagnosed on abdominal radiographs, but a large tumor in the stomach can occasionally be recognized as a soft tissue mass indenting the gastric air shadow. Rarely, benign GISTs in the stomach contain irregular streaks or clumps of mottled calcification that are visible on abdominal radiographs, barium studies, or computed tomography (CT) ( Fig. 31-14 ). Mucinous adenocarcinomas of the stomach may also calcify, but the calcification in these lesions tends to have a punctate, granular, or finely stippled appearance (see Chapter 32 ). The differential diagnosis for left upper quadrant calcification also includes calcified adrenal, renal, or splenic lesions.

Benign GISTs typically appear on barium studies as discrete submucosal masses ( Figs. 31-15 and 31-16 ). These tumors have the same radiographic features as intramural, extramucosal lesions elsewhere in the GI tract. When viewed in profile, the lesions have a smooth surface that is etched in white on double-contrast images, and their borders form right angles or slightly obtuse angles with the adjacent gastric or duodenal wall (see Fig. 31-15A ). When viewed en face, the intraluminal surface of these tumors has abrupt, well-defined borders (see Fig. 31-15B ). Because the overlying mucosa is usually intact, a normal areae gastricae pattern can sometimes be seen overlying these lesions.

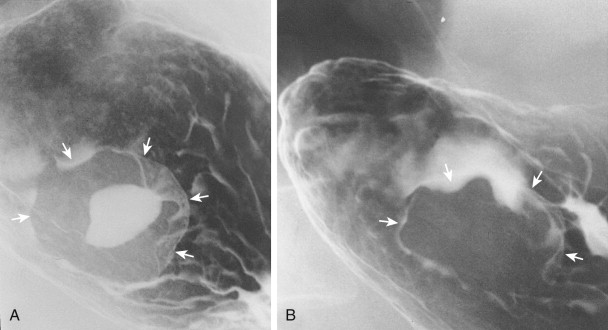

Gastric GISTs vary in size from tiny lesions of several millimeters to enormous masses that encroach substantially on the lumen. Tumors larger than 2 cm frequently contain areas of ulceration, manifested by a central barium-filled crater within the surrounding submucosal mass (see Fig. 31-16A ). Because of their characteristic appearance, centrally ulcerated GISTs viewed en face have been described as bull’s-eye or target lesions. Occasionally, a hanging droplet of barium (i.e., stalactite) on an anterior wall GIST can mimic the appearance of ulceration (see Fig. 31-15B ), but the stalactite can usually be recognized as a transient finding at fluoroscopy.

Because ulcerated GISTs may cause major upper GI bleeding, ulceration is generally considered an indication for surgery. Rarely, however, complete healing of ulceration in benign gastric GISTs can occur in patients treated conservatively with antisecretory agents (see Fig. 31-16B ), so medical treatment may lead to cessation of bleeding when surgery is contraindicated. If necessary, bleeding can also be controlled angiographically by selective embolization of feeding vessels.

Although most benign GISTs in the stomach have a typical submucosal appearance, exogastric tumors that grow outward from the stomach may be difficult to differentiate from extrinsic mass lesions. However, the presence of a central dimple or spicule at the apex of the mass should suggest an intramural rather than an extrinsic lesion. This area of tenting probably results from traction on the gastric wall by the base or pedicle of the mass as it enlarges. Other GISTs that grow intraluminally may develop pseudopedicles. Rarely, pedunculated antral GISTs may prolapse into the duodenum or act as the lead point for a gastrogastric or gastroduodenal intussusception ( Fig. 31-17 ).