(1)

Princess Elizabeth Hospital Le Vauquiedor St. Martin’s Guernsey, Channel Islands, UK

(2)

Brighton and Sussex Medical School, Brighton, England UK

Abstract

When Leborgne described the presence of calcification in breast cancer in 1951, he concluded that, with sufficient experience, it was easy to differentiate between benign and malignant calcification. This view was supported by Egan (1964), who stated that ‘The typical calcifications are so pathognomonic of carcinoma. They are so specific that in their presence, a histologic diagnosis of benign disease usually indicates that either the surgeon has selected the wrong tissue for biopsy or the pathologist is in error’. However, Egan later conceded that although calcifications provide clues to estimate the risk of carcinoma, the signs are so ‘nonspecific’ that all radiologically demonstrable clusters of stippled calcification require histological examination (Egan et al. 1980). This latter statement is in keeping with the view of most radiologists, in that, although there are some pathognomonic features of benign or malignant calcification, there are a considerable number of indeterminate calcifications that require further investigation and subsequent biopsy to exclude malignancy.

Learning Points

Calcification in some benign lesions such as oil cysts and of vascular origin has pathognomonic features.

Most calcifications reported in benign lesions are mammographically indeterminate.

In some cases calcification can differentiate benign from malignant lesions.

Breast calcifications consist of calcium phosphate or calcium oxalate.

Calcium oxalate is usually present in benign lesions and is a cause of absent calcification on microscopy and requires polarising light.

Calcium phosphate is more prevalent than calcium oxalate.

Calcium phosphate is found in both benign and malignant lesions.

13.1 Overview of Mammographic Calcification

When Leborgne described the presence of calcification in breast cancer in 1951s (Leborgne 1951), he concluded that, with sufficient experience, it was easy to differentiate between benign and malignant calcification. This view was supported by Egan (1964), who stated that ‘The typical calcifications are so pathognomonic of carcinoma. They are so specific that in their presence, a histologic diagnosis of benign disease usually indicates that either the surgeon has selected the wrong tissue for biopsy or the pathologist is in error’. However, Egan later conceded that although calcifications provide clues to estimate the risk of carcinoma, the signs are so ‘nonspecific’ that all radiologically demonstrable clusters of stippled calcification require histological examination (Egan et al. 1980). This latter statement is in keeping with the view of most radiologists, in that, although there are some pathognomonic features of benign or malignant calcification, there are a considerable number of indeterminate calcifications that require further investigation and subsequent biopsy to exclude malignancy.

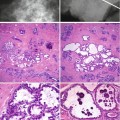

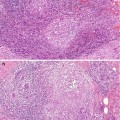

Microcalcification occurs in luminal secretions, necrotic debris within the stroma in association with degenerative conditions, scar tissue, foreign bodies or lymph nodes. Because of the heterogeneous appearance of the calcification, it is not always possible to confidently confer a diagnosis of benignity, unless the calcification is overtly vascular or within an oil cyst. Features that indicate benign calcification include: isolated round calcification, scattered punctate calcification as seen in sclerosing adenosis or ‘teacup’ calcification of microcysts (Heywang-Köbrunner et al. 2001; Lanyi 1986). Calcification with a lobular pattern is also generally associated with benign breast disease. Solitary, diffuse distribution throughout the parenchyma or symmetrical distribution also suggests benign calcification. Lucent-centred calcifications also denote benignity. These are usually seen in fat necrosis, calcified debris in ducts and occasionally in fibroadenomas (American College of Radiology 1998). Table 13.1 summarises some of the different patterns of benign calcification and related lesions.

Table 13.1

Morphological features associated with benign calcification

Morphological features of calcification | Associated lesions |

|---|---|

Shell-like calcification around a soft tissue density | Fibroadenoma, papilloma, oil cyst, foreign body reaction, e.g. silicone implant |

Granular | Fibroadenomatoid hyperplasia, stromal calcification |

Round calcifications with or without central radiolucency | Scars, fat necrosis, duct ectasia |

Coarse, popcorn-like or bizarre | Fibroadenoma, papilloma |

Coarse, needle-like +/− branching | Duct ectasia, scars, may be difficult to exclude ductal carcinoma in situ |

Parallel/serpentine | Vascular |

Teacup phenomenon | Fibrocystic change |

Rosette-like/morula-like clusters, usually multiple and symmetrical | Microcystic/blunt duct adenosis |

Widespread ill-defined/punctate | Involuted breast |

The nature of indeterminate calcifications can be confirmed only on histology, and this can exhibit either a psammomatous or an amorphous pattern. Both patterns of calcification are also associated with low- and high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), respectively, which could explain the indeterminate mammographic appearance.

The different patterns of calcifications are illustrated in the previous chapters in relation to specific conditions. However, it is important to reiterate that calcification in benign breast disease elevates the risk of malignancy to a higher level than if calcification was not present. In Dupont and Page’s (1985) report on benign proliferative disease, women with atypical hyperplasia had a relative risk of 4.4, and this increased to 6.5 if calcification was present. Although this study was on symptomatic women with benign disease, most atypical hyperplasias are usually associated with mammographic calcification. In a separate study on post-mortem tissue, Bartow et al. (1990) reported a high prevalence of increased breast density, microcalcification and epithelial hyperplasia in women aged 35–49 compared with women over 50 years. However, the association was not statistically significant (P ≥ 0.07).

13.2 Assessing Microcalcification

The presence of mammographic calcification is an important feature, which indicates underlying pathology within the breast tissue. Only 30–40 % of breast calcifications are malignant, the remainder being benign (Heywang-Köbrunner et al. 2001). The pattern of distribution and the size, shape and density of the calcification assist the radiologist in deciding whether a calcifying lesion is benign or malignant (Sickles 1986). Ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging have limited value in assessing calcifications.

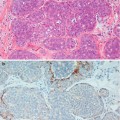

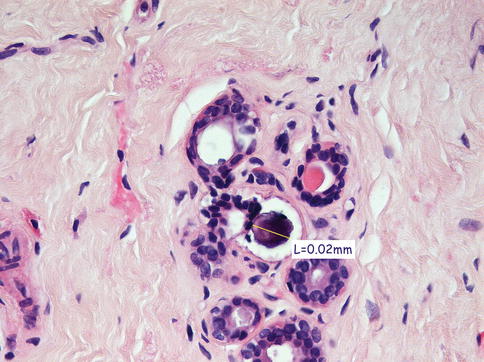

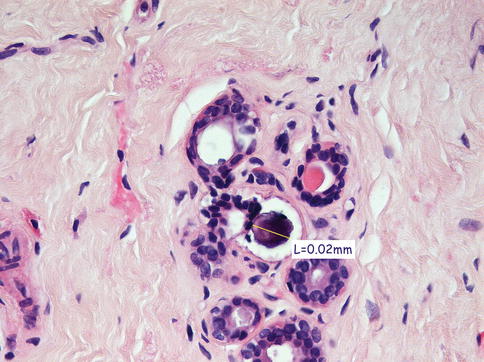

Mammographic calcifications more than 2 mm in maximum dimensions are termed macrocalcifications and those smaller than 1 mm, microcalcifications (Bun 2002). Involutional calcification in lobules tends to be elusive and difficult to identify mammographically. These calcifications are small, round and multiple, with a powdery appearance, and tend to be spread over a large area. Secretory calcifications are also small and multiple. Although these patterns of calcification can be detected mammographically in isolation or as part of sclerosing adenosis, the calcification is frequently identified on histology the breast tissue excised for unrelated pathology. It is important to accurately compare the mammographic and histological features in screen-detected calcification to ensure that the features in the histological sections represent the mammographic lesion. The presence of histological calcification in a needle core does not necessarily indicate appropriate sampling (Fig. 13.1).

Fig. 13.1

Isolated microcalcification in TDLU was not the part of the targeted radiological lesion. The microcalcification was too small to be detected mammographically, and the biopsy was reported as B1

Grunert and colleagues (2001

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree