LACRIMAL GLAND: ORBITAL PSEUDOTUMOR AND ACUTE AND CHRONIC INFECTIONS AND NONINFECTIOUS INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

KEY POINTS

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can almost always make the definitive diagnosis of a benign tumor or developmental mass of the cavernous sinus.

- Imaging findings based on patterns of involvement aid greatly in the differential diagnosis but are not tissue specific, and occasionally malignant disease and vascular malformations can mimic benign masses that arise in the region.

- Perineural spread of cancer to the cavernous must not be mistaken for a benign lesion—check the peripheral course of cranial nerve V in all cases.

- Imaging is essential in initial treatment planning and following surveillance strategies depending on the extent of disease and approach to treatment.

The epicenter of benign tumors and developmental masses may be within or adjacent to the cavernous sinus. They are typically well circumscribed; thus, an infiltrative morphology suggests an alternative diagnosis of inflammatory or malignant pathology. A benign tumor arising in the cavernous sinus other than a meningioma or neurogenic tumor is very unusual.

Meningiomas are by far the most common tumor of the cavernous and paracavernous region. Occasionally, very eccentric pituitary adenomas can mimic a meningioma.

A benign neurogenic tumor (Chapters 29) of the cavernous sinus arising from a nerve other than cranial nerve V is rare. A variety of benign bony origin conditions of central skull base bone origin may secondarily involve the cavernous sinus (Fig. 73.1).

Developmental masses that may primarily arise in the cavernous sinus region or involve it secondarily include dermoid and epidermoid cysts and vascular malformations most commonly referred to as hemangiomas.

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Embryology

The developmental factors that lead to the formation of dermoid and epidermoid cysts are discussed in Chapter 8; those related to the development of vascular malformations are discussed in Chapter 9.

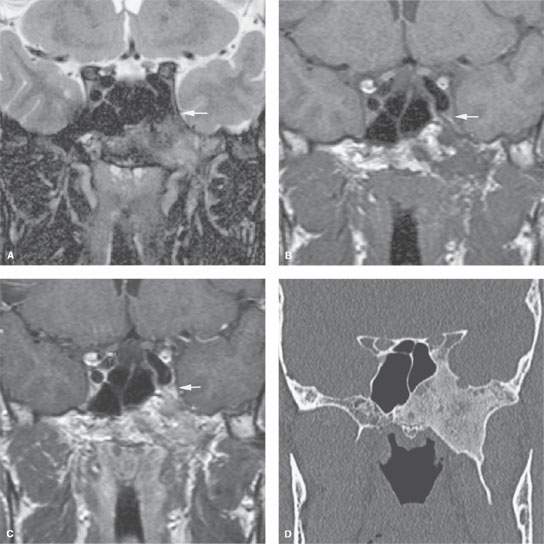

FIGURE 73.1. Fibrous dysplasia of the sphenoid causing visual field loss, diminished vision, and orbital pain on the left. A–C: Magnetic resonance study shows enlargement of the greater wing, pterygoid process, and floor of the sphenoid due to a lesion with mixed signal intensity on T2-weighted (A) and T1-weighted (B) images and inhomogeneous enhancement (C). There is extension into the cavernous sinus (arrow). D: Computed tomography shows classic fibrous dysplasia.

Applied Anatomy

The relevant anatomy of the cavernous sinus, orbit, eye, and optic nerve/sheath complex is discussed in detail in Chapter 44. The relevant anatomy of the central skull base is discussed in Chapter 78.

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

The cavernous sinus is studied with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) techniques described in detail in Chapters 44 and 45. Specific CT protocols by indications are detailed in Appendix A. Specific MR protocols by indications are outlined in Appendix B. Almost all studies to investigate cavernous sinus pathology are done with contrast.

Catheter angiography is used in some cases to evaluate pathology that might secondarily involve the carotid artery.

Pros and Cons

Disease of the cavernous sinus is studied primarily with CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI is far more definitive in its rendering of the cranial nerves within the cavernous sinus. MRI also establishes the dural relationships of masses more accurately than CT. MRA can usually simply and rapidly exclude an aneurysm or other vascular lesion.

CT is useful for establishing the nature and extent of bone changes that might aid in diagnosis and treatment planning. It is also very useful if the lesion is of bone origin (Fig. 73.1).

CT is also acceptable when MRI cannot be done for establishing the extent of disease. Computed tomographic angiography (CTA) is a good and perhaps preferred screening tool to exclude vascular lesions from the differential diagnosis when magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) cannot be done.

SPECIFIC DISEASE/CONDITION

Benign Tumors

Etiology

Benign tumors arising in the cavernous sinus other than a meningioma, or much less frequently a neurogenic tumor, are very unusual. Meningiomas can be induced by prior radiotherapy. Neurogenic tumors are often manifestations of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) or neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF-2). An eccentric pituitary adenoma may mimic a meningioma. Unusual or rare tumors may be of bone origin and only secondarily involve the cavernous sinus region.

Bone tumors run the full gamut of tissues of origin found in bone: osteogenic, chondrogenic, and those of fibro-osseous origin. Those lesions are discussed in detail in Chapters 37 through 41 (Fig. 73.1). Benign mesenchymal lesions of the cavernous sinus would be extraordinarily rare. Secondary involvement by pituitary tumors and juvenile angiofibromas is common, but the site of origin is usually not in question.

Developmental lesions only uncommonly present in the cavernous sinus region. Dermoid and epidermoid cysts and teratomas may arise from their region but more commonly involve it secondarily. Arachnoid cysts are typically those of the middle cranial fossa. Vascular malformations commonly referred to as hemangiomas can appear identical to a meningioma and are discussed in Chapter 75.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

These tendencies are discussed in the figures and chapters as follows:

Bone lesions (Fig. 73.1 and Chapters 38–42)

Bone lesions (Fig. 73.1 and Chapters 38–42)

Dermoids, epidermoids, and teratomas (Fig. 73.2 and Chapter 8)

Dermoids, epidermoids, and teratomas (Fig. 73.2 and Chapter 8)

Meningioma (Figs. 73.3–73.5 and Chapter 31)

Meningioma (Figs. 73.3–73.5 and Chapter 31)

Nerve sheath tumors (Figs. 73.6–73.8 and Chapter 29)

Nerve sheath tumors (Figs. 73.6–73.8 and Chapter 29)

Hemangiopericytoma (Fig. 73.9 and Chapter 25)

Hemangiopericytoma (Fig. 73.9 and Chapter 25)

Hemangioma (malformation) (Fig. 73.10 and Chapter 9)

Hemangioma (malformation) (Fig. 73.10 and Chapter 9)

Pituitary adenoma (Fig. 73.11 and Chapter 32)

Pituitary adenoma (Fig. 73.11 and Chapter 32)

Chordoma (Fig. 73.12 and Chapter 34)

Chordoma (Fig. 73.12 and Chapter 34)

Clinical Presentation

Facial pain of trigeminal origin is a common feature of cavernous sinus tumors. This may be typical trigeminal neuralgia or atypical facial pain. Involvement of all three divisions of the trigeminal nerve strongly points to the cavernous sinus as a source of pathology. Trigeminal nerve involvement may cause paresthesias and numbness as well as pain.

Ocular motility disturbance with diplopia and pupillary dysfunction is common due to cranial nerves III, IV, and VI involvement. Rarely, the diplopia is painful. Horner syndrome may be present, or the pupil may be fairly nonreactive if both the sympathetic and parasympathetic portions of the third cranial nerve are involved. Decreased visual acuity is possible.

Pathophysiology and Patterns of Disease

Dermoid and related developmental cysts arise from sources described in Chapter 8 (Fig. 73.2).

Meningiomas (Chapter 31) commonly arise along or involve the dura of the cavernous sinus.1, 2 Their biologic activity is usually that of a slowly evolving, dural-based mass; a more aggressive growth pattern is possible.

Meningiomas of the cavernous sinus are most commonly based along its outer dural wall (Fig. 73.3). Because the cavernous sinus dura forms the diaphragma sellae medially and also folds inward to form the dural membrane separating the pituitary fossa from the cavernous sinus, meningiomas can arise from these structures as well. This results in several different growth patterns1: meningiomas projecting external to the cavernous sinus from its outer dural reflection2 (Fig. 73.3); those arising from the diaphragma sellae that project into the suprasellar space, possibly impinging on the optic chiasm (Fig. 73.4); and those arising from the internal dural reflection and remaining within the cavernous sinus or the sella3 (Fig. 73.4). Meningiomas characteristically grow on both sides of the dural membrane of origin (Fig. 73.5). These features help to differentiate cavernous meningiomas from other intracavernous masses, such as nerve sheath tumors, metastases, aneurysms, and parasellar extensions of pituitary adenomas.1,2

Nerve sheath tumors (Chapter 29) usually arise from the trigeminal nerve, its ganglion, or one of its branches and perhaps most commonly are associated with NF-1 and NF-2 (Fig. 73.6). They may be distinguished from meningiomas by their growth within the trigeminal cistern and along the divisions of that nerve. Neurogenic tumors of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI are rare (Fig. 73.7). Cranial nerve III is most common, and the growth vector will follow the nerve (Fig. 73.8).

Other neurogenic tumors have no particular predilection for the cavernous sinus.

Hemangiopericytoma (Fig. 73.9) and hemangioma (Fig. 73.10) can mimic the appearance of a nerve sheath tumor, or more likely, a meningioma, and it is difficult to accurately anticipate those diagnoses prior to biopsy.

Pituitary adenomas (Fig. 73.11 and Chapter 32) extend laterally into the cavernous sinus. Since cavernous sinus extension is difficult or impossible to resect completely, one of the main aims of imaging these lesions is to determine whether the cavernous sinus is involved. Pituitary adenomas exhibiting parasellar extension will (on imaging) typically demonstrate a connection between the intrasellar tumor and mass within the cavernous sinus. Interrupted filling of medial cavernous sinus venous spaces may be the earliest sign of cavernous sinus involvement.3 Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR or CT may be used to evaluate these behaviors. Other criteria used to assess possible invasion are the degree of encasement of the cavernous carotid artery, extension past reference lines drawn through the medial and lateral margins of the carotid artery, and analysis of the size and shape of the cavernous sinus.4, 5

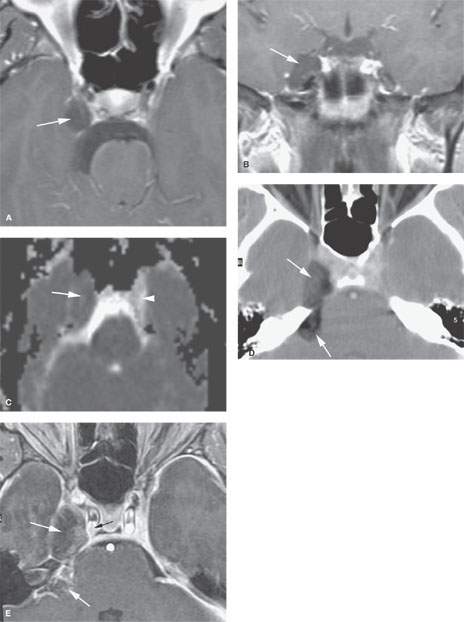

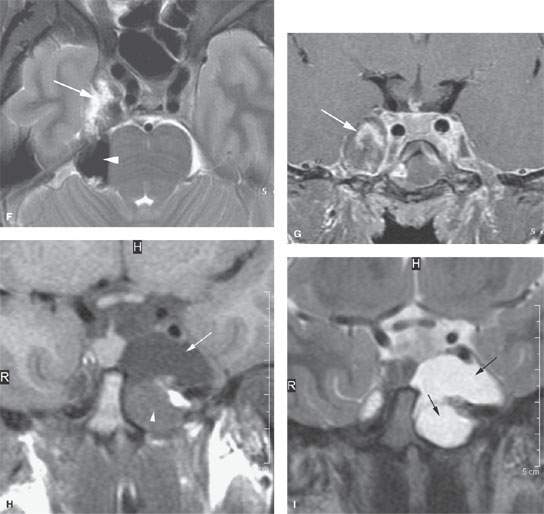

FIGURE 73.2. Three patients with developmental cysts involving the cavernous sinus. A–C: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study in Patient 1. In (A), the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image shows a cystic mass involving the cavernous sinus (arrow). In (B), the coronal image confirms the location of the cyst (arrow) and compression of the trigeminal cistern since no rootlets are visible within the cystic structure. In (C), the diffusion-weighted image shows restricted diffusion (arrow) compared with unrestricted fluid motion on the normal side (arrowhead). (NOTE: This is a dermoid cyst of the cavernous sinus region.) D–G: Computed tomography and MRI studies in Patient 2. In (D), a fat-containing mass involves the cavernous sinus and extends into the posterior fossa over the petrous ridge (arrows). In (E), the contrast-enhanced T1W image shows a not entirely fatty mass (arrows) in the same region as (D), compressing but not arising from the cavernous segment of the carotid artery (black arrow). In (F), the T2-weighted (T2W) fat-suppressed image shows the complex mass to be partially fluid (arrow) and partially fatty (arrowhead) in nature. In (G), the contrast-enhanced coronal image shows the complex mass (arrow) that could be mistaken for an aneurysm or other mass. (NOTE: This was a complex dermoid cyst of the cavernous sinus that at first observation on MRI could easily be mistaken for a partially thrombosed aneurysm.) H, I: MRI study in Patient 3. In (H), the non–contrast-enhanced T1W image shows a complex cystic mass with two main areas, one with likely more macromolecule content (arrowhead) than the other (arrow). In (I), the T2W image shows both areas to be of mainly fluid content (arrows). The difference on the T1W image in (H) likely is based on protein content of the cyst. (NOTE: This is a proven cystic teratoma of the cavernous sinus region.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree