CAVERNOUS SINUS: MALIGNANT TUMORS

KEY POINTS

- The imaging findings in tumors of the cavernous sinus are often very specific or at least highly suggestive of malignant involvement.

- Always be sure to look for perineural sources of a cavernous sinus mass, as this can markedly alter medical decision making and limit the morbidity of tissue sampling.

- Imaging findings based on patterns of involvement aid greatly in the differential diagnosis but are not tissue specific, and occasionally inflammatory disease can mimic malignancy and histologic confirmation of disease that appears to be isolated to the cavernous sinus is necessary to confidently arrive at an appropriate plan of management.

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can almost always substantially aid in medical decision making in malignant tumors of the cavernous sinus.

- Imaging is essential in initial treatment planning and following surveillance strategies depending on the extent of disease and approach to treatment.

The epicenter of cavernous sinus malignant tumors may be within or adjacent to the cavernous sinus. They are typically of an infiltrative morphology that may suggest an alternative inflammatory etiology. Malignant tumors arising in the cavernous sinus other than lymphoma are very unusual. Malignancies of the cavernous sinus are far more likely to be contiguous spread from the nasopharynx, sinuses, and nasal cavity either directly or perineurally, although metastasis to the cavernous sinus may be blood borne or spread via the cerebrospinal fluid and meninges. Perineural spread may also arise from sites more remote, such as the skin. Pituitary malignancies are rare; however, when they occur, they spread directly to the cavernous sinus.

A variety of bony-origin primary tumors of the central skull base in addition to bony metastases may secondarily involve the cavernous sinus.

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Applied Anatomy

The relevant anatomy of the cavernous sinus is discussed in detail in Chapter 44. The relevant anatomy of the central skull base is discussed in Chapter 78.

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

The cavernous sinus is studied with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) techniques described in detail in Chapters 44 and 45. Specific CT protocols by indications are detailed in Appendix A. Specific MR protocols by indications are outlined in Appendix B. Almost all studies to investigate cavernous sinus pathology are done with contrast.

Catheter angiography is used in some cases to evaluate pathology that might secondarily involve the carotid artery.

Fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) and radionuclide bone scans might be used to determine whether the cavernous sinus disease is part of a systemic malignancy or diffuse metastatic disease or to search for a primary source.

Pros and Cons

Disease of and within the cavernous sinus is studied primarily with CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI is excellent in its rendering of the cavernous sinus and contiguous orbital apex and surrounding cisterns. MRI is more sensitive than CT to subtle meningeal pathology. MRI is far more definitive in its rendering of the cranial nerves within and leading to the cavernous sinus, making it the primary study for perineural and endoneural spread of tumor. It is also preferred to establish spread along vessels to the cavernous sinus. It demonstrates intracranial growth of these neoplasms and their possible intracranial complications better than CT. MRI can also screen more definitively for additional similar or associated tumors or multifocal disease that can shift the diagnostic considerations considerably.

CT is a reasonable first choice in patients who are too sick or for some other reason unable to complete a very high quality, free of motion artifact, MRI examination. CT is an acceptable secondary screening tool for identifying associated intracranial spread or complications. Computed tomographic angiography (CTA) is a good and often preferred screening tool to search for vascular involvement or a vascular abnormality as an alternative diagnosis. It is also acceptable when MRI cannot be done for establishing the extent of perineural, perivascular, and meningeal disease.

CT is very useful for establishing the nature and extent of bone changes that might aid in diagnosis and treatment planning. It is also very useful if the lesion is of bone origin.

FDG-PET is not specific enough to be useful in the differential diagnosis of cancer and inflammatory lesions, and the proximity of the cavernous sinus to normally hypermetabolic brain further limits its usefulness. It can be used effectively to find a primary site or assess the extent of malignant disease elsewhere in the body.

SPECIFIC DISEASE/CONDITION

Malignant Tumors

Etiology

Malignancies of the cavernous sinus other than lymphoma (Fig. 74.1) are far more likely to be contiguous direct or perineural spread from an adjacent anatomic locale. Contiguous direct cavernous sinus spread is most common in nasopharyngeal (Fig. 74.2) and sinonasal cancers (Fig. 74.3). Direct invasion occurs via skull base erosion or through the foramen lacerum. Perivascular spread along the carotid artery may cause invasion without bone destruction. Perineural spread is usually seen along branches of the trigeminal nerve (V2 and V3) when the tumor involves the infratemporal fossa or masticator space.1,2 Perineural spread may also arise from sites more remote, such as the skin (Fig. 74.4). It is extremely important to understand that a cavernous sinus malignancy might actually be due to retrograde perineural spread along branches of the trigeminal nerve. This is most common in skin cancer, but the source may be lymphoma or a primary source elsewhere in the head and neck region.

A variety of bony-origin primary tumors of central skull base bone origin in addition to bony metastases may secondarily involve the cavernous sinus (Fig. 74.5). Bone tumors run the full gamut of tissues of origin found in bone: osteogenic, chondrogenic, and those of fibro-osseous origin. Those lesions are discussed in detail in Chapters 37 through 41. Most are benign, but a malignant tumor is possible. Chordoma may present with cavernous sinus localization.

Pituitary malignancies are rare; however, when they occur, they spread directly to the cavernous sinus. An eccentric benign pituitary adenoma may mimic a malignant tumor (Chapter 32).

Malignant mesenchymal lesions of the cavernous sinus are extraordinarily rare, but secondary involvement by rhabdomyosarcoma is not uncommon in sinonasal and nasopharyngeal primary tumors.

Metastases to the cavernous sinus from tumor elsewhere, such as the breast, lung, or prostate, also can occur (Fig. 74.6).

Prevalence and Epidemiology

These trends are discussed in chapters indicated in the previous section.

Clinical Presentation

Relentlessly progressive facial pain of trigeminal origin is a common feature of cavernous sinus malignancies. This may be typical trigeminal neuralgia but is more usually atypical facial pain. Involvement of all three divisions of the trigeminal nerve strongly points to the cavernous sinus as a source of pathology. Trigeminal nerve involvement may cause paresthesias as well as pain. Headache is also a common complaint.

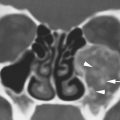

FIGURE 74.1. Three patients with lymphoma involving the cavernous sinus, all associated with different spread patterns. A: Patient 1. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image showing neurotropic lymphoma involving the trigeminal cistern bilaterally (arrows) and both oculomotor nerves (arrowheads). B–D: Patient 2 with lymphoma spreading to the cavernous sinus from the skull base. In (B), contrast-enhanced computed tomography study shows lymphoma involving the cavernous sinus on the left for certain (arrow) and possibly on the right. Multifocal involvement of the preseptal soft tissues and within the muscle cone (arrowheads) suggests a systemic disease. In (C), bone windows show the destructive lesion of the clivus (arrow) and infiltration of the pterygopalatine fossae (arrowheads). In (D), contrast-enhanced T1W image shows the extensive involvement of the clivus with a very aggressive pattern of growth into the nasopharyngeal and prevertebral soft tissues (arrowheads) as well as into the cavernous sinus (arrow). E: Patient 3 who had HIV and involvement of the cavernous sinuses (arrows) due to diffuse dural spread of tumor.

FIGURE 74.2. Two patients with spread of nasopharyngeal cancer to the cavernous sinus, illustrating different patterns of spread. A, B: Patient 1 presenting with Horner syndrome and facial pain. In (A), the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image shows nasopharyngeal cancer in this patient spreading to the cavernous sinus (arrowheads) along the internal carotid artery (arrow). In (B), the contrast-enhanced T1W image shows spread also along the trigeminal nerve into the cavernous sinus region (arrows). C–E: Patient 2 had complaints of nose obstruction and ear pain. In (C), on a T2-weighted axial image, a large nasopharyngeal carcinoma is seen (*). There is no perivascular spread along the internal carotid artery. In (D), on the contrast-enhanced T1W fat-suppressed image, the mass seems to be contained within the pharyngobasilar fascia (arrowheads), which attaches medial to the oval foramen. There is, however, tumor extension to the inferior cavernous sinus through the foramen lacerum (arrow). In (E), the intracavernous extension through the foramen lacerum is confirmed on this contrast-enhanced T1W fat-suppressed image. The enhancing tumor mass (*) grows medial to the carotid artery (C).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree