CAVERNOUS SINUS: NONINFECTIOUS INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS AND ACUTE AND CHRONIC INFECTIONS

KEY POINTS

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings in inflammatory conditions involving the cavernous sinus are often nonspecific, but imaging patterns of involvement can greatly aid in the differential diagnosis of causative pathology in many patients.

- Imaging can identify causative conditions for infections that can lead to improved outcomes if treated promptly.

- Imaging can identify visual pathway complications such as detachments, retained foreign bodies, and compressive factors that may lead to improved outcomes if treated promptly.

The noninfectious inflammatory conditions including pseudotumor (or Tolosa-Hunt syndrome [THS]) commonly involve the cavernous sinus. Other noninfectious inflammatory conditions may be local or related to systemic disease. These include the granulomatoses and histiocytoses that may present and appear identical to pseudotumor or lymphoma. These diseases are discussed in general in chapters on sarcoidosis (Chapter 18), Wegener granulomatosis (Chapter 17), and Langerhans histiocytosis (Chapter 19).

Infections may also be local or related to systemic disease. These conditions may be due to secondary spread from the eye (Chapter 50), optic nerve and sheath (Chapter 56), and extraconal (Chapter 62) and preseptal compartments (Chapter 70) or from sinonasal disease such as pyogenic sinusitis or rhinocerebral mucormycosis or other fungal infection (Chapters 84–86).

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Applied Anatomy

The relevant anatomy of the cavernous sinus, orbit, eye, and optic nerve/sheath complex is discussed in detail in Chapter 44. The relevant anatomy of the paranasal sinuses is discussed in Chapter 78.

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

The cavernous sinus is studied with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) techniques described in detail in Chapters 44 and 45. Specific CT protocols by indications are detailed in Appendix A. Specific MR protocols by indications are outlined in Appendix B. Almost all studies to investigate cavernous sinus pathology are done with contrast.

Catheter angiography is used in some cases to evaluate pathology that might secondarily involve the carotid artery.

Pros and Cons

Disease of the cavernous sinus is studied primarily with CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI is far more definitive in its rendering of the cranial nerves within the cavernous sinus. MRI is also far more sensitive than CT to possibly related meningeal pathology. MRI detects other intracranial involvement with these inflammatory processes and their intracranial complications much better than CT. MRI can also screen for related vascular complications and perivascular spread, especially in the case of fungal disease.

CT is typically used in acute situations of an aggressive infectious process perhaps with a sinonasal origin or as an emergent evaluation in patients too sick or for some other reason unable to complete a very high quality, free of motion artifact, MRI examination. CT is, however, a reasonable secondary screening tool for identifying intracranial extension of disease and intracranial complications. CT angiography is a good and perhaps preferred screening tool to search for vascular complications such as infectious aneurysms and cavernous sinus thrombosis.

SPECIFIC DISEASE/CONDITION

Noninfectious Inflammatory Disease Including Pseudotumor (Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome)

Etiology

THS, or cavernous sinus pseudotumor, is an acquired immune-based process that lacks systemic involvement (Chapters 18 and 57). This is probably a variation of idiopathic orbital inflammatory syndrome (IOIS), which involves the orbital apex and cavernous sinus region.1

Other noninfectious inflammatory diseases may also be local or related to systemic disease. The cavernous sinus may be secondarily involved due to pathology involving the eye (Chapter 49) and optic nerve/sheath complex (Chapter 56) or that arising in the brain, meninges, or paranasal sinuses and central skull base. The granulomatoses and histiocytoses are infiltrating processes that may present and appear identical to IOIS or lymphoma. These diseases are discussed in general in chapters on sarcoidosis (Chapter 18), Wegener granulomatosis (Chapter 17), and Langerhans histiocytosis (Chapter 19).

Prevalence and Epidemiology

THS is a sporadic, rare disease with no known predisposing factors.

The prevalence and etiology of the granulomatoses, histiocytoses, and autoimmune disease that affect the muscle cone are discussed in the chapters on those entities as noted in the previous section (Chapters 18 and 57).

Clinical Presentation

Constant, boring, severe pain is a characteristic feature of THS that is typically present from its onset. Ocular motility disturbance with diplopia and pupillary dysfunction are common due to cranial nerves III, IV, and VI involvement. Lid ptosis may be present because of cranial nerve III involvement. Trigeminal nerve involvement may cause forehead paresthesias as well as pain. It can also cause Horner syndrome. Visual loss from extension of the process to involve the optic nerve is not uncommon. Remissions and relapses are common.

Other noninfectious inflammatory conditions such as the granulomatoses and histiocytoses may have an identical presentation without pain being a prominent part of the clinical situation. Those diseases might also have symptoms of sinonasal involvement or meningeal disease and possibly pituitary– hypothalamic dysfunction.

Pathophysiology and Patterns of Disease

THS is probably a variation of IOIS, which involves the orbital apex and cavernous sinus region1 (Figs. 18.17, 57.5, and 72.1). It is a diagnosis of exclusion. The process is unilateral in the vast majority of cases. In bilateral cases, it is often asymmetric. Bilaterality raises the likelihood of an alternative diagnosis of systemic disease such as lymphoma (Chapter 74) or sarcoidosis.

Spread to the superior orbital fissure and orbital apex to or from the cavernous sinus is possible (Fig. 57.5). It is probably reasonable to lump the steroid responsive granulomatous inflammation of the cavernous sinus into the generalized category of IOIS/pseudotumor.1 Continued spread to the middle and posterior cranial fossa is also possible.

The Langerhans cell histiocytoses may involve the cavernous sinus in children, usually as a bony lesion with secondary cavernous sinus extension (Fig. 72.2). However, skull base involvement is rarely seen. This may be related to differences in development of the skull base and the calvarium: The skull base develops from cartilaginous neurocranium by endochondral ossification, whereas the calvarium originates from the mesenchymal membranous neurocranium by intramembranous ossification.2 There may be accompanying meningeal disease and involvement of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis.3

Granulomatoses such as sarcoidosis and Wegener granulomatosis most commonly involve the cavernous sinus as a result of spread from the orbit or sinonasal region (Fig. 72.3). Wegener granulomatosis rarely involves the cavernous sinus and essentially never as an isolated form of the disease. Spread to the cavernous sinus is almost always from obvious sinonasal and orbital involvement. Sarcoidosis is the most common of the granulomatoses that will present with the meninges of the cavernous sinus as the sole site of involvement. There is, however, usually accompanying meningeal disease and involvement of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis as a clue to the correct diagnosis (Figs. 18.12 and 77.2).

Manifestations and Findings

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

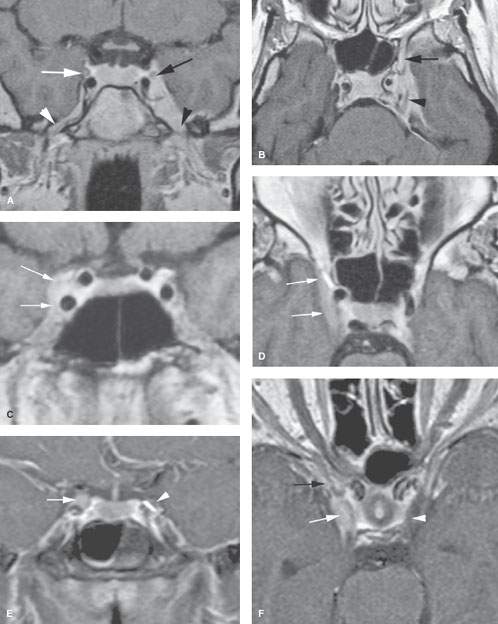

The general morphology of inflammatory disease as seen on CT and MRI is described in Chapter 13. On both CT and MRI, this inflammatory morphology appears as an indistinct, contrast-enhancing, infiltrating process involving the cavernous sinus, trigeminal cistern, and overlying dura and possibly leptomeninges often with contiguous disease at the orbital apex and superior orbital fissure (Figs. 18.17, 57.5, and 72.1). Circumferential narrowing of the anterior genu and clinoidal segments of the carotid may be seen on any vascular imaging study.

THS is usually iso- or slightly hyperintense to skeletal muscle on T2-weighted images, the relatively low signal intensity probably being related to its fibrocollagenous component and dense cellularity (Figs. 18.17, 57.5, and 72.1). Unfortunately, tumors and other infiltrating processes can have an identical appearance.

The other noninfectious inflammatory diseases really have no distinguishing features from THS. Associated sinonasal and intracranial findings as seen on parts of those structures included in the field of view may help with the differential diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

From Clinical Data

Tumors and other infiltrating processes can have an appearance identical to THS. The age of the patient and associated systemic disease helps narrow the differential to THS versus one or two other choices, one of them almost always being lymphoma, in most cases. The clinical presentation of a unilateral, painful ophthalmoplegia, painful proptosis will almost always push the main diagnosis to THS. After an extensive laboratory workup to include angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), serum protein electrophoresis, circulating antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (c-ANCA), HIV, and thyroid function tests and usually cerebral spinal fluid study to rule out other serious conditions, the diagnosis is made by a therapeutic trial of steroids or cyclophosphamide and/or biopsy.

The granulomatoses and histiocytoses may have clinical evidence of multisystem involvement or general constitutional symptoms that will suggest those as an alternative consideration.

From Supportive Diagnostic Techniques

An infiltrating cavernous sinus process with indistinct margins is perhaps the most common appearance on CT or MR images (Figs. 18.17 and 72.1). THS will mainly be confined to the cavernous sinus, perhaps, in a limited number of cases, extending to the superior and inferior orbital fissure region or orbital apex. THS is usually iso- or slightly hyperintense to skeletal muscle on T2-weighted images, with the relatively low signal intensity probably being related to its fibrocollagenous component and dense cellularity. Unfortunately, tumors and other infiltrating processes can have an identical appearance.

More diffuse patterns and bilateral disease is possible. Associated sinonasal, brain or meningeal disease, or systemic involvement may aid in the differential diagnosis. Fungal disease often enters the differential diagnosis and is more likely if there is adjacent sinus or another contiguous site of disease.

Laboratory testing might support Wegener granulomatosis with a positive c-ANCA or sarcoidosis with a positive ACE. An elevated sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein may favor an inflammatory etiology over a neoplastic etiology. Biopsy may be necessary to exclude lymphoma or other tumors and to confirm pseudotumor. Lymphoma is typically the most common working differential diagnostic possibility in the neoplastic category.

FIGURE 72.1. Magnetic resonance imaging of three patients with Tolosa-Hunt syndrome (pseudotumor) affecting the cavernous sinus region. A, B: Patient 1 presenting with ophthalmoplegia and facial pain. In (A), the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image shows the abnormal thickening of the cavernous sinus and paracavernous region on the left side with obvious abnormality of the V3 on the left (black arrowhead) compared to the normal on the right (white arrowhead). On the normal side, cranial nerve III (white arrow) appears normal; that on the left appears compressed and perhaps abnormally enhancing in part (black arrow). In (B), the T1W axial section shows the marked thickening of the V2 branch (arrow) within the foramen rotundum and shows cranial nerve III surrounded by abnormal enhancing tissue. C, D: Contrast-enhanced T1W images of Patient 2 presenting with ophthalmoplegia and facial pain. In (C), there is abnormal focal enhancement of the cavernous sinus in its upper, outer portion (arrows). This would explain the patient’s third cranial nerve dysfunction. The abnormality is confirmed on the axial view (arrows in D). E, F: Contrast-enhanced T1W images of Patient 3 with third cranial nerve dysfunction, diminished vision, and facial pain. In (E), there is abnormal enhancement of cranial nerve III on the right (arrow) compared to the normal opposite side (arrowhead). In (F), this appeared to be due to extension of disease from the region of the superior orbital fissure (black arrow) to the cavernous sinus (white arrow) compared to the normal side (white arrowhead).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree