CAVERNOUS SINUS: VASCULAR ABNORMALITIES

KEY POINTS

- The imaging findings in vascular cavernous sinus lesions are usually definitive, but catheter angiography occasionally is necessary to complete the initial diagnostic evaluation.

- Imaging can help identify risk of imminent complications and direct therapy.

This chapter discusses vascular conditions that primarily involve the cavernous sinus. Cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST) is usually seen as a complication of cavernous carotid fistula (CCF) or pyogenic sinusitis (Chapter 72). CCFs occur spontaneously in the case of ruptured occult cavernous segment carotid aneurysms, in the evolution of carotid dissections that extend into the cavernous carotid segment, and due to traumatic laceration. Aneurysms within the cavernous sinus are either occult and small or are large and may be referred to as giant aneurysms, producing compressive cranial nerve symptoms.1 If they rupture, they may produce CCFs.

Venolymphatic malformations that involve the orbit extend to or rarely may present exclusively as a cavernous sinus mass. These malformations mimic vascular meningiomas; their true nature may not be appreciated until they are biopsied. Vascular malformations are discussed in general in Chapter 9, as they relate specifically to the orbit and visual pathways in Chapter 59, and to the cavernous sinus in Chapter 73.

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Applied Anatomy

The relevant anatomy of the cavernous sinus and related vascular structures is discussed in detail in Chapter 44. The relevant anatomy of the central skull base is discussed in Chapter 78.

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

The cavernous sinus is studied with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) techniques described in detail in Chapters 44 and 45. Specific CT protocols by indications are detailed in Appendix A. Specific MR protocols by indications are outlined in Appendix B. Almost all studies to investigate cavernous sinus pathology are done with contrast. Protocols for the study of possible vascular conditions routinely include magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or computed tomographic angiography (CTA).

Pros and Cons

Disease of the cavernous sinus is studied primarily with CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI is far more definitive in its rendering of the internal anatomy of the cavernous sinus. MRA can usually simply and rapidly exclude an aneurysm or other vascular lesion; in the screening setting, MRI and MRA are used to establish the presence of an aneurysm that is presenting with signs and symptoms of a cavernous sinus mass (Chapters 73 and 74).

CTA is the preferred screening tool to confirm a CCF. Catheter angiography is done as a prelude to endovascular treatment or when MRI/MRA and/or CTA are not definitive enough to confirm or exclude that possibility.

Both CT and MRI are suitable for confirming the presence of CST. They both may be able to identify the cause.

Controversies

Catheter angiography remains the mainstay of diagnosis and is always a prelude to endovascular treatment. This study will most accurately depict the flow dynamics and angioarchitecture of the lesions as described in the following section on pathophysiology of CCF. Newer 320 MDCT technology or its equivalent may nearly fully replace catheter angiography for diagnosis and therapy planning.

SPECIFIC DISEASE/CONDITION

Cavernous Carotid Fistula and Bland Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis

Etiology

CST is usually seen as a complication of CCF or pyogenic sinusitis (Figs. 72.4 and 72.5 and Chapter 72). CCFs occur spontaneously in the case of ruptured occult cavernous segment carotid aneurysms, in the resolution or resorptive phase of internal carotid dissections that extend into the cavernous carotid segment, and due to posttraumatic laceration (Figs. 75.1–75.3). The latter occur in the context of substantial head trauma and often are associated with skull base fracture.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

CST and CCF occur in adults and pediatric patients with no significant gender predilection. CST has become much rarer in recent years because of the much improved antibiotics that are generally available.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms are most typically acute orbital injection, swelling, and proptosis. There may be pulsating exophthalmos and an orbital bruit in some cases of CCF. If complicated by CST, pain and ophthalmoplegia are also likely. Bilateral sequential periorbital swelling associated with headache and usually mental status change is almost pathognomonic for septic CST, which is a true emergency (Figs. 72.4 and 72.5 and Chapter 72). A slow-flow CCF may present only with a sixth cranial nerve palsy (Fig. 75.2). Vision may be lost if lesions go untreated.

Pathophysiology and Patterns of Disease

CST causes enlargement of the cavernous sinus and/or occlusion of some or all of its vascular spaces. Enlargement and thrombosis of the superior ophthalmic vein, sphenoparietal sinus, clival venous plexus, or petrosal sinuses may occur (Figs. 72.4 and 72.5 and Chapter 72). Edema within the orbital fat is due to the resultant vascular congestion.

CCF occurs spontaneously in the case of ruptured occult cavernous segment carotid aneurysms (Fig. 75.3). It may also occur in the resolution or resorptive phase of internal carotid dissections that extend into the cavernous carotid segment. Posttraumatic laceration of the cavernous carotid may result in a CCF most often after substantial head trauma with associated skull base fracture (Fig. 75.1). CCFs by nature imply a high-volume, high-pressure shunt. They must be differentiated from dural fistulas of the cavernous sinus region, which are low-pressure, low-volume shunts from dural cavernous sinus segment branches of the distal internal carotid artery to sinusoids of the cavernous sinus (Fig. 75.3).

These arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) and arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) are common cavernous sinus/orbital problems that often present in the clinical context of a “red or injected eye.” Many arise in the cavernous sinus and secondarily involve the orbit or manifest orbital symptoms or signs. They are vasoformative lesions responding to a congenital or acquired artery to vein shunt. Their growth is in proportion to mechanical rheologic forces associated with the size and complexity of the arteriovenous shunt. Since treatment varies significantly, a basic understanding of their angioarchitecture and pathophysiologic mechanisms is useful even to the noninterventionalist.

The two most common arteriovenous shunts involving the orbit are (a) high-volume, high-flow fistulas involving the cavernous segment of the internal carotid artery and the cavernous sinus (Figs. 75.1 and 75.3) and (b) low-volume, low-pressure dural AVFs or AVMs involving the dural arteries of the cavernous sinus (Fig. 75.2). Transmitted arterial pressure in carotid cavernous and dural fistulas to the cavernous sinus reverses flow from the ophthalmic veins. This retrograde drainage creates orbital edema and injection of the conjunctiva and sclera. The features are more dramatic with the higher pressures in a direct CCF (Figs. 75.1 and 75.3). Another complication of cavernous arteriovenous shunts is cavernous sinus venous thrombosis.

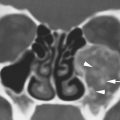

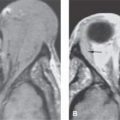

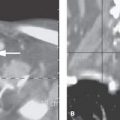

FIGURE 75.1. A patient with a high-flow carotid cavernous fistula (CCF). Computed tomographic angiography was done. Sectional images from that study are provided. A: Axial sections show the cavernous segment of the artery on both sides to be of relatively normal size (arrows). The fistula is on the left, but there is filling of the cavernous sinus and clival plexus sinusoids bilaterally (arrowheads). B: Coronal section showing the internal carotid arteries (arrows) and filling of cavernous sinus sinusoids (arrows). C: Section through the orbit showing enlargement of the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins in this predominately arterial phase image (arrows) on the side of the CCF and less filling on the side opposite (arrowhead) consistent with the flow dynamics of a lesion that is on the left. D: Sagittal reformation showing the enlargement of orbital veins (arrows).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree