Certificate of Need (CON) programs represent a patchwork of state regulatory programs across the United States that regulate the availability of selected health care services. Thirty-six states maintain laws designed to ensure access to health care services, maintain or improve quality, and control capital expenditures on health care services and facilities by limiting unnecessary health facility construction and checking the acquisition of major medical equipment. This article discusses the history of CON and explores controversies surrounding the current state of CON regulations.

- •

Certificate of Need (CON) is a method of regulating specific health care services at the state level.

- •

The covered clinical services vary among the individual states.

- •

CON can assist in reducing health care costs and maintaining quality of patient care if properly administered.

Introduction

Certificate of Need (CON) programs represent a patchwork of state regulatory programs across the United States that regulate the availability of selected health care services. Thirty-six states maintain laws designed to ensure access to health care services, maintain or improve quality, and control capital expenditures on health care services and facilities by limiting unnecessary health facility construction and checking the acquisition of major medical equipment. This article discusses the history of CON and explores controversies surrounding the current state of CON regulations.

CON legislation originally was introduced by the government in an attempt to solve the cost increase and oversupply problems. This legislation required potential acquirers of medical facilities or technology above a certain monetary value to demonstrate the clinical need for acquiring this capability and qualifications for responsibility of ownership.

CON laws primarily focused on hospitals and nursing homes to halt needless duplication of services and excess capacity. CON regulations were seen as a way to control the “medical arms race” by having organizations demonstrate need for a facility, service, or equipment before investing in them. The term medical arms race implies competition by service expansion and proliferation of new technology. In the 1980s some states expanded their CON regulations to control the proliferation of ambulatory care services as well. Other secondary objectives of CON were to promote access and quality.

Issues surrounding overuse of imaging due to the expansion of availability of imaging centers demonstrate the concept of moral hazard, illustrating supply-driven demand. Moral hazard arises when individuals engage in behaviors under conditions such that their privately taken actions affect the probability distribution of the outcome. By having more scanners in a geographic area, the probability that more studies will be ordered and performed (by virtue of easy access/availability) is increased.

History of CON legislation

In the mid twentieth century, the nation’s aging medical infrastructure and workforce were poorly prepared to adequately serve the needs of soldiers returning from World War II and the subsequent increase in the nation’s population. There was an insufficient number of hospitals built during the Great Depression, resulting in inadequate medical care for returning soldiers. Congress responded to the situation by passing 2 laws: The Hill-Burton Act of 1946 and the Health Professions Act of 1963. The Hill-Burton Act was passed with the goal of improving medical supply with focus on facility capacity. This act encouraged community planning and hospital construction using Federal subsidies. The Health Profession Act of 1963 focused on the medical workforce. The federal government also expanded access to health care through the Kerr-Mills Act of 1960 for welfare recipients and the 1965 Social Security Act for the elderly and the poor.

Health care spending was rising significantly by the late 1960s. Health care spending had grown at an annual rate of 3.7% in the 1940s and 1950s, but in the 1960s rose at a rate of 5.8%. As a result, the health care expenditures per capita more than tripled between 1940 and 1970. In particular, hospital expenditures more than tripled, to $27.6 billion in a little more than the 10 years from 1960 to 1970.

Three main factors contributed to the rising costs of health care: (1) the implementation of Medicare, (2) the widespread adoption of a traditional fee-for-service (FFS) payment system, and (3) the diffusion of new medical technology. The Medicare health insurance program had a great impact on increasing costs of health care. The Social Security Act signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson on July 30, 1965, established the Medicare and Medicaid health insurance programs. The Medicare program provided health insurance for the elderly and the Medicaid program insured the poor. Through Medicare, currently one of the largest health insurance programs in the world, most elderly patients had nearly full-coverage insurance. As a result, the patients generally ignored the price of the services when choosing a facility. With these plans, patients selected the hospitals based on hospital reputation and their perception of the quality of care provided. In turn, this led hospitals to adopt the latest technology and expand offerings to attract more patients.

The FFS system also contributed to the rising costs of health care. Under FFS, hospitals were reimbursed by insurers for all expenses incurred, regardless of the cost, necessity of the service, or quality of the facility. Under FFS, medical services often expanded beyond their actual need.

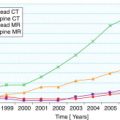

The technological change that took place during this period is also another primary cause of rapid increase in health expenditure. One of the single most expensive and rapidly diffused medical technologies of that time period was computed tomography (CT) scanning in the mid 1970s. The CT scanner, developed in England by EMI, rapidly changed the diagnostic process for many conditions. Because of its diagnostic capabilities, the CT scanner became rapidly embraced by both patients and clinicians. Sophisticated medical technology is expensive: the unit costs exceed US$1 million. These factors, among others, led to the establishment of CON legislature.

Several steps preceded the common establishment of CON programs by the US states. In an effort to halt rising costs of health care, the federal government and the states decided to implement a health care regulation model originally initiated in Rochester, New York. The Rochester Patient Care Planning Council, composed of insurers, patients, and providers, evaluated the community’s hospital needs and determined what services were needed and not needed.

The Comprehensive Health Planning and Services Act signed by President Johnson in 1966 authorized the states to establish planning processes that would rationally allocate federally granted health-related funding. New York established mandatory CON processes in 1966, followed by Maryland, Rhode Island, and District of Columbia. About half of the states had adopted CON laws by 1974. The National Health Planning and Resources Development Act (NHPRDA) of 1974 required the remaining states to establish CON programs that would review and grant approvals to any facility or equipment projects that would expand health care services by any provider.

Only a few years after the CON programs were federally mandated, they came under increasingly severe criticism and, ultimately, were abandoned prematurely by the federal government. During President Ronald Reagan’s first term (1981–1985), CON was dismissed by policy makers as an unjustified federal imposition on states and a barrier to competitive dynamics. Congress let the NHPRDA expire in 1986, and federal funding of state CON programs ended the following year. Within 2 years, 10 states eliminated their CON programs. In the 1990s and early 2000s, 5 additional states repealed their CON laws in full. While most states have chosen to keep CON, nearly all of them have modified their CON programs to exempt some medical services.

History of CON legislation

In the mid twentieth century, the nation’s aging medical infrastructure and workforce were poorly prepared to adequately serve the needs of soldiers returning from World War II and the subsequent increase in the nation’s population. There was an insufficient number of hospitals built during the Great Depression, resulting in inadequate medical care for returning soldiers. Congress responded to the situation by passing 2 laws: The Hill-Burton Act of 1946 and the Health Professions Act of 1963. The Hill-Burton Act was passed with the goal of improving medical supply with focus on facility capacity. This act encouraged community planning and hospital construction using Federal subsidies. The Health Profession Act of 1963 focused on the medical workforce. The federal government also expanded access to health care through the Kerr-Mills Act of 1960 for welfare recipients and the 1965 Social Security Act for the elderly and the poor.

Health care spending was rising significantly by the late 1960s. Health care spending had grown at an annual rate of 3.7% in the 1940s and 1950s, but in the 1960s rose at a rate of 5.8%. As a result, the health care expenditures per capita more than tripled between 1940 and 1970. In particular, hospital expenditures more than tripled, to $27.6 billion in a little more than the 10 years from 1960 to 1970.

Three main factors contributed to the rising costs of health care: (1) the implementation of Medicare, (2) the widespread adoption of a traditional fee-for-service (FFS) payment system, and (3) the diffusion of new medical technology. The Medicare health insurance program had a great impact on increasing costs of health care. The Social Security Act signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson on July 30, 1965, established the Medicare and Medicaid health insurance programs. The Medicare program provided health insurance for the elderly and the Medicaid program insured the poor. Through Medicare, currently one of the largest health insurance programs in the world, most elderly patients had nearly full-coverage insurance. As a result, the patients generally ignored the price of the services when choosing a facility. With these plans, patients selected the hospitals based on hospital reputation and their perception of the quality of care provided. In turn, this led hospitals to adopt the latest technology and expand offerings to attract more patients.

The FFS system also contributed to the rising costs of health care. Under FFS, hospitals were reimbursed by insurers for all expenses incurred, regardless of the cost, necessity of the service, or quality of the facility. Under FFS, medical services often expanded beyond their actual need.

The technological change that took place during this period is also another primary cause of rapid increase in health expenditure. One of the single most expensive and rapidly diffused medical technologies of that time period was computed tomography (CT) scanning in the mid 1970s. The CT scanner, developed in England by EMI, rapidly changed the diagnostic process for many conditions. Because of its diagnostic capabilities, the CT scanner became rapidly embraced by both patients and clinicians. Sophisticated medical technology is expensive: the unit costs exceed US$1 million. These factors, among others, led to the establishment of CON legislature.

Several steps preceded the common establishment of CON programs by the US states. In an effort to halt rising costs of health care, the federal government and the states decided to implement a health care regulation model originally initiated in Rochester, New York. The Rochester Patient Care Planning Council, composed of insurers, patients, and providers, evaluated the community’s hospital needs and determined what services were needed and not needed.

The Comprehensive Health Planning and Services Act signed by President Johnson in 1966 authorized the states to establish planning processes that would rationally allocate federally granted health-related funding. New York established mandatory CON processes in 1966, followed by Maryland, Rhode Island, and District of Columbia. About half of the states had adopted CON laws by 1974. The National Health Planning and Resources Development Act (NHPRDA) of 1974 required the remaining states to establish CON programs that would review and grant approvals to any facility or equipment projects that would expand health care services by any provider.

Only a few years after the CON programs were federally mandated, they came under increasingly severe criticism and, ultimately, were abandoned prematurely by the federal government. During President Ronald Reagan’s first term (1981–1985), CON was dismissed by policy makers as an unjustified federal imposition on states and a barrier to competitive dynamics. Congress let the NHPRDA expire in 1986, and federal funding of state CON programs ended the following year. Within 2 years, 10 states eliminated their CON programs. In the 1990s and early 2000s, 5 additional states repealed their CON laws in full. While most states have chosen to keep CON, nearly all of them have modified their CON programs to exempt some medical services.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree