CERVICAL ADENOPATHY DUE TO BENIGN AND MALIGNANT SYSTEMIC DISEASES

KEY POINTS

- Cervical adenopathies due to benign and malignant systemic diseases often mimic reactive adenopathy, which is a common finding on imaging studies, especially in young children.

- The imaging ordered should be used as much as possible to separate reactive from other nodal pathology to advance the diagnostic process as efficiently as possible.

- These adenopathies may be distinguished from reactive, metastatic, and infectious adenopathy with imaging in many cases based on the distribution and morphology of the pathologic nodes.

- Reactive adenopathy and that due to lymphoproliferative disease may not be distinguishable on any imaging study, and follow-up, at least by clinical examination, is essential to exclude a malignant etiology.

- Causative or related extranodal pathology associated with the adenopathy may be seen on the study and be very useful to advance the decision-making process.

- The imaging study may provide clues as to the etiology of these benign and malignant adenopathies.

- The imaging study may show extranodal complications of these benign and malignant adenopathies.

INTRODUCTION

Cervical adenopathy is often the presenting feature of both benign and malignant systemic diseases that requires treatment. At times, such adenopathy must initially be distinguished from infectious adenopathy and adenopathy reactive to infection (Chapter 158) and cervical metastatic disease (Chapter 157) as well as other lateral neck masses. The systemic diseases that manifest as lymph adenopathy are highlighted here but are discussed in detail from a pathophysiologic perspective in dedicated chapters of Section II that will be referenced as necessary in the following text.

Clinical Presentation

The primary presentation of cervical lymphadenopathy is usually a “solitary” neck mass of uncertain etiology or generalized palpable lymph node prominence without associated signs or symptoms or other physical findings. More often, physical examination will reveal multiple abnormal nodes—either unilateral or bilateral—depending on the etiology. Bilateral adenopathy is most common in systemic diseases.

Tenderness and fever may be present and are more likely in inflammatory conditions than in the diseases discussed in this chapter. In these diseases, if there is fever it is likely to be “low grade,” and if there is tenderness it is likely to be minimal.

APPLIED ANATOMY

The anatomy of interest is discussed in detail in Chapter 149 and reviewed with a focus on metastatic adenopathy and with regard to its application in evaluating neck masses of uncertain etiology or due to an “unknown primary” in Chapter 157.

IMAGING APPROACH

The techniques for computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) studies of the infrahyoid neck for various clinical situations, including lymphadenopathies, are presented in Appendixes A and B.

Standard ultrasound imaging and flow-related techniques are used with transducers appropriate for the depth of penetration required. The rationale for these protocols is presented specifically in Chapter 149.

The approach with radionuclide studies depends on the specific aim of the examination. Most current usage is limited to known or suspected cancer evaluation with fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET). The use of FDG-PET should be limited in these masses since the diagnosis will be established by a combination of the clinical setting, associated findings in other organ systems, imaging, and tissue sampling of the nodes when necessary. Nodes due to these diseases are likely to be hypermetabolic regardless of the specific etiology.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND PATTERNS OF DISEASE

These abnormal nodes generally will enlarge and most often retain an otherwise normal architecture (Fig. 159.1), perhaps except for some increased perfusion manifested by anatomic factors such as more prominent vessels, increased enhancement, and changes in measurable flow parameters regardless of the etiology (Fig. 159.2), thereby mimicking reactive nodes. A clue to their difference from simple reactive adenopathy may be as simple as the nodes enlarging to a degree far beyond that seen in a simple reactive node and/or the distribution of the enlarged nodes. These nodes might also express a vascularity that is also well beyond that of simple reactive nodes; in such cases, the vascular pedicle will typically be enlarged and flow increased via the hilar vascular pedicle. The capsule of the lymph node may also manifest in the hypervascularity of the node. The measurable CT, MR, and ultrasound parameters will then manifest variable degrees of increased flow (Figs. 159.2–159.5). The subject node or nodes may also manifest changes in their internal architecture that may range from a relatively subtle upset to fairly gross morphologic changes that can be seen and/or measured on imaging studies (Figs. 159.6–159.10). Treated nodes, host factors, or aggressive disease can result in gross tumor or tissue necrosis in the node, which tends to manifest centrally as opposed to the early peripheral manifestations of “solid” nodal metastatic disease (Chapter 157).

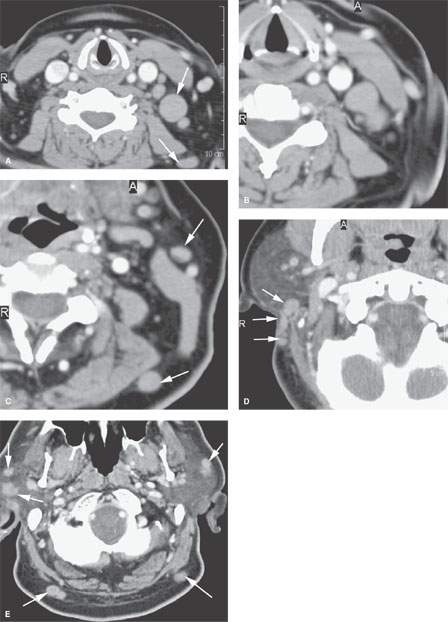

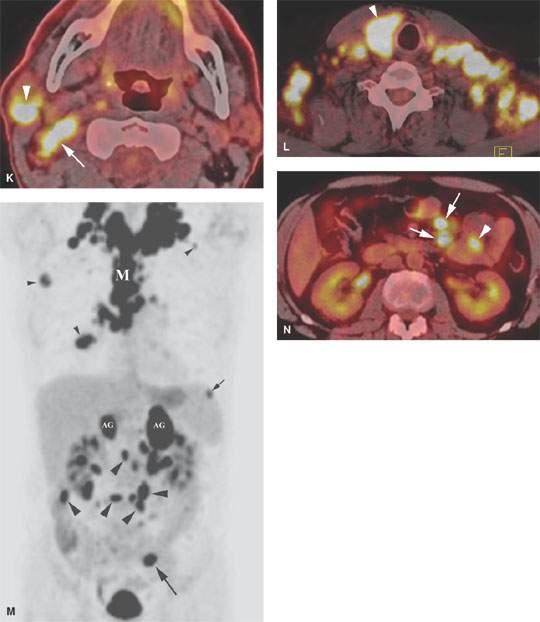

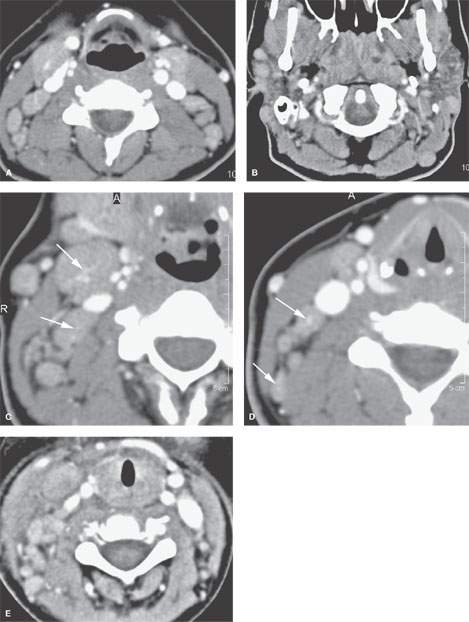

FIGURE 159.1. Three patients with lymphoma in whom the distribution of adenopathy is a major factor in supporting that diagnosis. A–F: Patient 1. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showing typical enlargement and distribution of nodes due to lymphoma with a nonspecific internal morphology. The nonspecific morphology of the nodes is their homogeneous density without evidence of hypervascularity or related perinodal changes. This morphology, given the distribution including parotid, retromastoid, posterior neck, and level 5 nodes, strongly indicates lymphoma as a diagnosis. G, H: Patient 2. Contrast-enhanced CT showing generalized lymphadenopathy and nodes distributed in an unusual location along the superior laryngeal neurovascular bundle (arrows). There is also a suggestion of some increased vascularity around the capsule of the nodes (arrowheads). The overall morphology and unusual distribution make lymphoma likely, and this was confirmed. I: Patient 3. A patient with homogeneous-appearing nodes in the zygomatic division of the group (arrows). The homogeneous morphology, unusual location, and lack of any skin cancer as a cause strongly suggest lymphoma as an etiology, and this was confirmed clinically. J–N: Coronal positron emission tomography (PET) image through the neck (J) demonstrating extensive multifocal uptake through the necks bilaterally (right greater than left) that is extending into the mediastinum (arrow in J). The axial, fused PET-CT images through the upper (K) and lower (L) neck show that the involvement is not limited to nodal groups II through V as suggested by the coronal PET image but also involves a parotid lymph node on the right (arrowhead in K) and the thyroid gland (arrowhead in L). The coronal PET image through the body (M) demonstrates additional extensive uptake in the mediastinum (M in M), chest cavities bilaterally (small arrowheads in M), spleen on the left (small arrow in M), adrenal glands (AG in M) bilaterally, abdominal cavity bilaterally (large arrowheads in M), and left pelvis (large arrow in M). The axial, fused PET-CT through the mid abdomen (N) reveals that the abdominal uptake is not only involving mesenteric lymph nodes (arrow in N) but also focal involvement of a small bowel loop (arrowhead in N) on the left side. All of these imaging findings are consistent with diffuse lymphoma. The arrow in B points to an abnormal group IIB lymph node.

These nodes, regardless of etiology, will contain activated immune-competent cells that are increased in number, so the nodes may appear hypermetabolic on FDG-PET studies reflecting, nonspecifically, the energy demand of the cellular immune response.

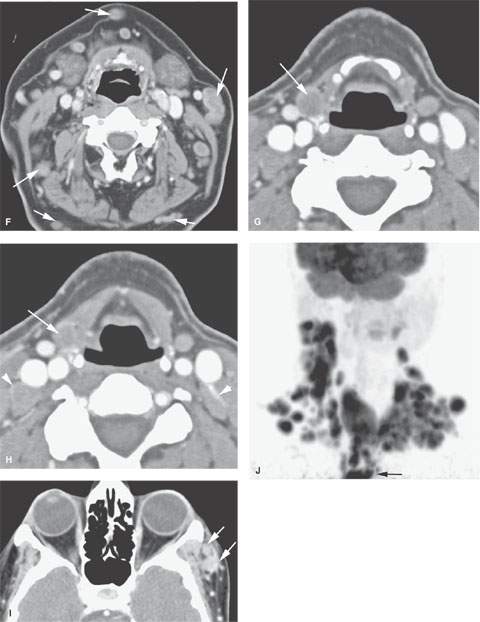

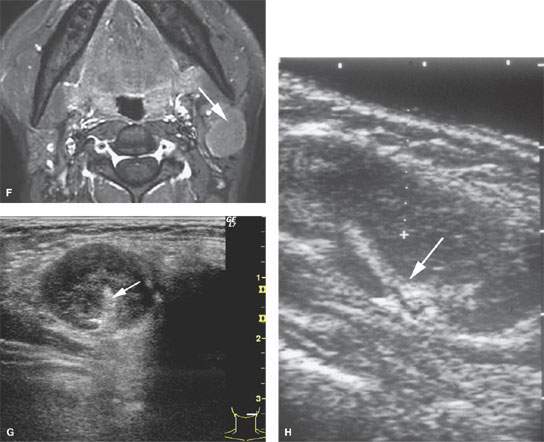

FIGURE 159.2. Lymphoma internal morphology can vary from that seen in Figure 159.1. Five patients illustrate variable morphology as it pertains to hypervascularity. A–D: Patient 1. On this contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), there is generalized bilateral adenopathy. The nodes appear increased in size, with their parenchyma generally enhancing more than usual without focal defects, and there are prominent vascular pedicles in the involved nodes. In (B), there is a distribution in the parotid and posterior neck nodes, which as in (A) strongly suggests lymphoma. Close-up views in (C) and (D) of the nodes involved with lymphoma. Note the very prominent vascular pedicle even in some of the smaller nodes (arrows). E: Patient 2, a child with predominately unilateral adenopathy. Contrast-enhanced CT shows some of the nodes to enhance homogeneously and others to be less enhancing, and there is some perinodal soft tissue edema. The neck mass was nontender and subsequently proved to be due to lymphoma. F: Patient 3. A lymphomatous node (arrow) as seen on a contrast-enhanced T1-weighted fat-suppressed image showing the node largely replaced by tumor cells and minimal capsular hyperemia. G: Patient 4. Ultrasound showing echogenic hilar structures in lymphoma (arrow). H: Patient 5. Ultrasound showing a node retaining its shape but enlarged. The node has prominent hilar architecture (arrow) and could have easily been considered reactive; it turned out to be due to lymphoma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree