CERVICAL ADENOPATHY: REACTIVE AND INFECTIOUS

KEY POINTS

- Reactive adenopathy is a common finding on imaging studies and in young children can be considered “physiologic.”

- Reactive adenopathy may be distinguished from lymphoproliferative, metastatic, and infectious adenopathy with imaging in many cases based on the distribution and morphology of the pathologic nodes.

- Causative pathology for the adenopathy may be seen on the study.

- Reactive adenopathy may evolve to more specific expressions of the disease process, such as suppurative adenopathy in pyogenic infections.

- Reactive adenopathy and that due to lymphoproliferative disease may not be distinguishable on any imaging study, and follow-up, at least by clinical examination, is essential to exclude a malignant etiology.

- The imaging study may provide clues as to the etiology of infectious adenopathy.

- The imaging study may show extranodal complications of infectious adenopathy.

INTRODUCTION

Reactive nodes range from incidental findings to a feature that is useful in the differential diagnosis to a situation that must be distinguished from significant treatable pathology. At times, such adenopathy must initially be distinguished from malignant adenopathy (Chapter 157) and that due to benign systemic diseases (Chapter 159) as well as other lateral compartment masses such as infected branchial apparatus cysts (Chapter 153).

Clinical Presentation

The primary presentation of reactive adenopathy is most often a perceived “solitary” neck mass of uncertain etiology or generalized palpable lymph node prominence without associated signs or symptoms or other physical findings. More often, physical examination will reveal multiple abnormal nodes—either unilateral or bilateral—depending on the etiology.

Tenderness and fever may be present and are much more likely in infectious and noninfectious inflammatory conditions (Chapters 13, 16, 17–20, and 159). For infectious adenopathy, an inciting condition such as pharyngitis or skin infection may be a prominent part of the presentation.

APPLIED ANATOMY

The anatomy of interest is discussed in detail in Chapter 149 and reviewed with a focus on metastatic adenopathy in Chapter 157 and with regard to its application in evaluating neck masses of uncertain etiology or due to an “unknown primary.”

IMAGING APPROACH

The techniques for computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) studies of the infrahyoid neck for various clinical situations, including lymphadenopathies, are presented in Appendixes A and B. Standard ultrasound imaging and flow-related techniques are used with transducers appropriate for the depth of penetration required. The rationale for these protocols is presented specifically in Chapter 149.

The approach with radionuclide studies depends on the specific aim of the examination. Most current usage is limited to known or suspected cancer evaluation with fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET). The use of FDG-PET should be very limited, if used at all, in conditions that are likely to be inflammatory since the diagnosis will be established by a combination of the clinical setting, imaging, and tissue sampling of the nodes or aspiration when necessary. Reactive and infectious nodes are likely to be hypermetabolic regardless of the etiology because the process will activate immune-competent cells in the nodes, by definition making the cells hypermetabolic and therefore fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) avid. Reactive nodes are a common source of false-positive findings in patients with head and neck cancer.

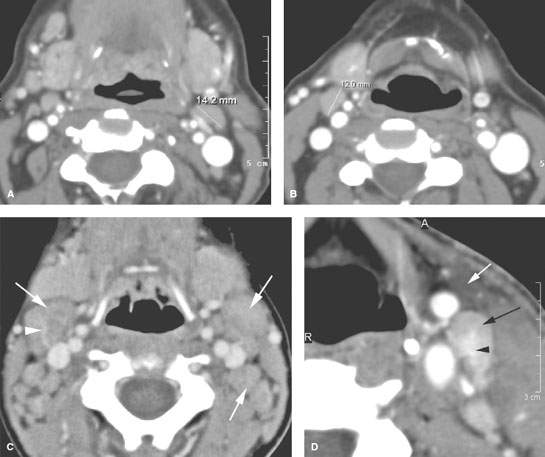

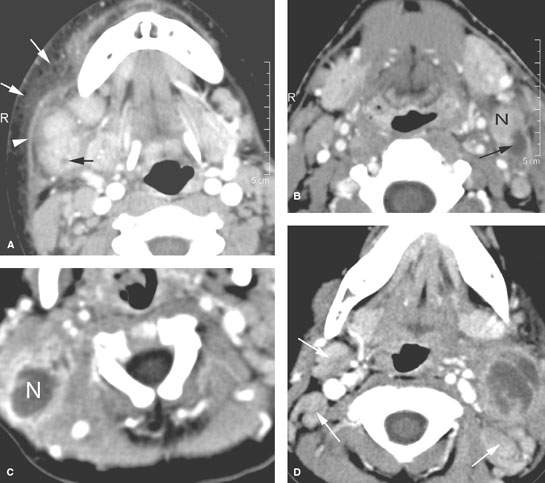

FIGURE 158.1. Patients with a spectrum of normal large reactive nodes studied with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and in one case ultrasound. A, B: Patient 1. Large nodes at level 2 in an adult. This is a common normal variation that points out the futility of using size criteria for any serious clinical decision making. C: Patient 2. Enlarged nodes, well over 2 cm in maximum short axis dimension, at level 2 in a child. This is a common normal variation that points out the total futility of using size criteria for any serious clinical decision in younger children. In this case, the nodes enhance slightly (arrows), and there is a prominent vascular pedicle in one (arrowhead). D: Patient 3, an adult with a node of typically reactive morphology in that its parenchyma enhances diffusely (black arrow), and it has prominent hilar blood vessels (arrowhead). There is also related edema in the anterior triangle fat (white arrow) deep to the superficial fascia, which is thickened. E–H: Patient 4, a child presenting with an abnormal mass at level 1A. In (E), a CT study shows the mass to be related to two enlarged lymph nodes (arrows). In (F), ultrasound shows the two lymph nodes. A longitudinal image (G) of one of the nodes shows a fairly typical nodal architectural pattern with some central echoes probably reflecting increased hypervascular structures (arrows). Vessels outside the node are also noted (arrowheads). Vascular ultrasound (H) shows the increased flow within the hilar vessels of this reactive node. The nodes resolved without treatment. I: Contrast-enhanced CT study of Patient 5 with retropharyngeal infection showing that homogeneously enhancing reactive nodes (arrows) are present in levels 2 and 5 on the right and to the lesser extent in level 2 on the left. Note that the reactive enhancement is greater on the right, which is consistent with that being the side of greatest involvement. J, K: Patient 6, a child with a reactive level 6 node (arrows) that resolved spontaneously. A contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image is shown in (J), and a T2-weighted image is shown in (K).

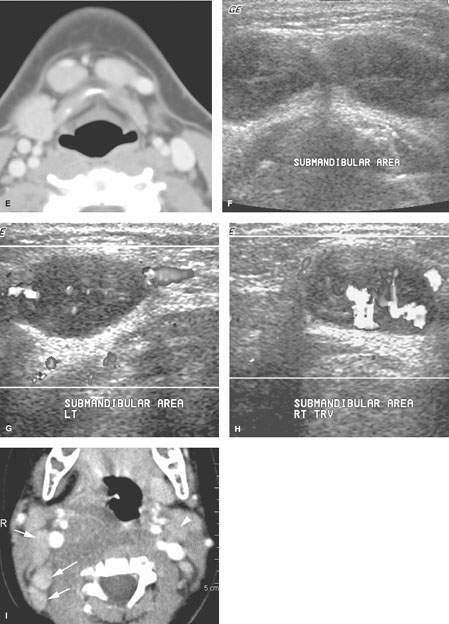

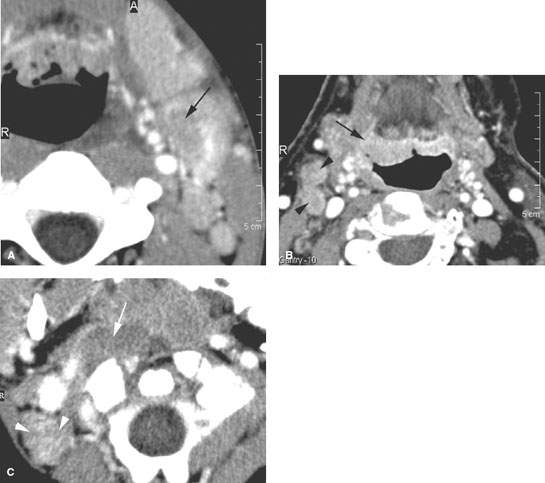

FIGURE 158.2. Three patients with contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans showing pre- or early suppurative changes in infected cervical nodes. A: Patient 1. Level 2 node with a “presuppurative” cellulitic focus (arrow). The next step is usually frank suppurative necrosis. B: Patient 2 with right-sided otalgia and level 2 adenopathy. This chronic tonsillitis mimicked a cancer in that there is a suggestion of early deep infiltration in what is a primarily exophytic tissue (arrows) and possible defects in enlarged nodes (arrowheads). All changes resolved on antibiotics. Biopsy showed only inflamed lymphatic tissue. The subtle areas of low density in the nodes were likely early presuppurative foci. C: Pediatric Patient 3 with retropharyngeal inflammation. The study shows enhancement within the node either due to general reactive nodal changes or early suppurative changes (arrow) and inhomogeneity in the reactive level 2B node (arrowheads).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND PATTERNS OF DISEASE

Reactive nodes generally will enlarge and retain an otherwise normal architecture (Fig. 158.1). The vascular pedicle typically will enlarge, and flow will be increased via the hilar vascular pedicle. The capsule of the lymph node may also manifest the physiologic hypervascularity of the node. Measurable CT, MR, and ultrasound parameters will manifest variable degrees of hypervascularity as increased blood flow by whatever parameter chosen1–7 (Fig. 158.2).

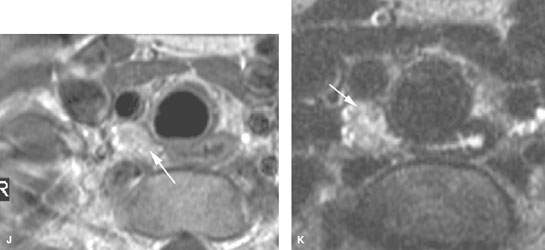

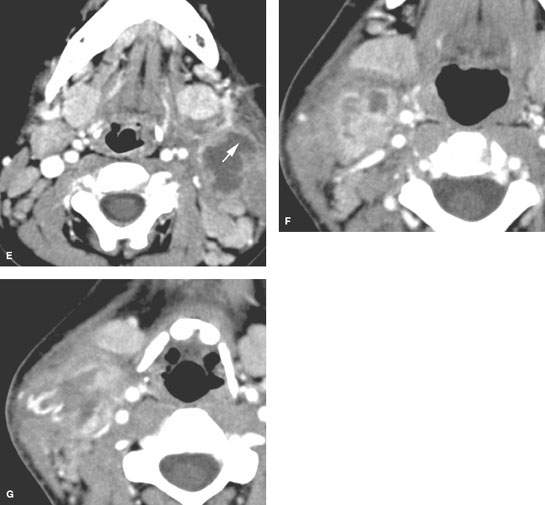

Infectious nodes may undergo focal and diffuse architectural changes. In pyogenic infections, this will reflect a cellulitic type or “presuppurative” phase followed by various degrees of liquefaction that tends to be central but may be more peripheral within the node (Fig. 158.2). Depending on the virulence of the infection, host factors, and treatment status, there will be capsular reactive changes and perinodal inflammatory changes (Figs. 158.2–158.7). At some point, the suppurative node becomes equivalent to an abscess, or purulent material can rupture from the node and produce a true deep neck abscess (Fig. 158.3G,H). Later-stage or healing changes may include dystrophic calcification (Fig. 158.6). Viral infections will result in typically reactive-appearing nodes with little, if any, capsular or perinodal findings suggestive of infection (Fig. 158.1). Lower-grade or partially treated infectious adenopathy may show a hybrid reactive-suppurative appearance (Figs. 158.7–158.9).

FIGURE 158.3. Five patients with pyogenic suppurative lymphadenopathy shown on contrast-enhanced computed tomography studies. A: Patient 1 had early suppurative adenopathy with a very intense surrounding cellulitis. There is a small suppurative focus (black arrow) in one of several enlarged enhancing nodes. There is extensive subcutaneous edema (white arrows) and thickening of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (arrowheads) due to surrounding cellulitis. B: Patient 2 had an inflammatory level 2B node (N) with an obvious suppurative focus (arrow). C: Patient 3 had a suppurative level 5A node (N) with the morphology of an abscess, it did not necessarily require drainage for treatment. D, E: Patient 4 with pharyngitis and secondary level 2 pyogenic suppurative adenitis. There is extensive necrosis within the affected level 2A nodes. Level 2B nodes and levels 2A and 2B on the right show nodal enlargement with generally reactive changes (arrows). In (E), the aggregated suppurative lymph node has begun to penetrate through the capsule of the node (arrow). Despite this early capsule penetration, the adenopathy was successfully treated with antibiotics. F, G: Patient 5 with pyogenic suppurative adenopathy that broke down to form a deep neck abscess. The lower section in (G) shows the breach of the node capsule (arrows) and surrounding cellulitis in this now deep neck abscess.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree