CERVICOTHORACIC JUNCTION: BRACHIAL PLEXUS BENIGN AND MALIGNANT TUMORS

KEY POINTS

- The origin of a brachial plexopathy is often not understood from the physical examination and clinical circumstances and may acutely threaten one or more other important and sometimes vital functions.

- Imaging can most often provide a very likely diagnosis.

- Imaging is critical to proper medical decision making beyond the diagnosis.

- Imaging-guided biopsy may be useful in more difficult diagnostic cases.

The general approach to mass lesions of the cervicothoracic junction (CTJ) is presented in Chapter 163 and should be reviewed at this time if necessary. This chapter presents examples of the benign and malignant tumors that occur in the brachial plexus in both pediatric and adult patients. These tumors may present as a plexopathy and/or as a mass that might potentially produce a plexopathy.

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS IN DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The anatomy of the brachial plexus and its relationship to the CTJ is presented initially in Chapter 149. This anatomy is also presented in a focused review in Chapter 163 as a foundation for the diagnostic approach to masses of the CTJ region that involve the brachial plexus. Those sources of anatomy information should be reviewed at this time, if necessary. The zones of the plexus at risk for compression are discussed in Chapter 165.1,2

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects and Pros and Cons

The detailed factors related to producing optimal imaging strategies and protocols for this region of anatomy are discussed in detail in Chapters 149 and 163. In summary, ultrasound is of limited use in brachial plexus masses except when the plexopathy is accompanied by signs and symptoms due to possible vascular occlusion that might be monitored with Doppler techniques. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the primary diagnostic tool in most instances of plexopathy when there is not an acute vascular component to the presentation.

The ideal MRI pulse sequence choices for a brachial plexus study would be those done with homogenous fat suppression across the range of the required T1 and T2 weighting necessary for a definitive study. Unfortunately, this remains a goal even when optimal receiver coil design is available because of the inhomogeneity of the B0 magnetic field related to coil loading challenges in this odd-shaped anatomic region. Newer parallel imaging water/fat separation techniques show some promise for improvement over frequency-selective fat suppression, but widespread application and validation of this approach for brachial plexus evaluation is not currently available. So, while fat-suppressed images are often “recommended” for brachial plexus evaluation, they are often unacceptably degraded and considerably prolong the scanning session, often with limited additional yield of diagnostic information.

Axial acquisitions remain the mainstay for basic analysis. Those images must include both sides if subtle pathologic changes must be detected. Moreover, acquisitions must include the entire axillary sheath whenever causative pathology might involve the distal brachial plexus. Coronal images are useful. Sagittal images are overrated for their utility and the first thing that can be eliminated in these protocols that are often far too complex. Studies must frequently include acquisitions with closely coupled receivers, such as dedicated shoulder coils, for the best images. These more localized techniques eliminate the ability to compare both sides comprehensively unless multiplexed in a manner that allows both sides to be studied with the highest possible detail.

In summary, excellent-quality, definitive brachial plexus imaging is not simple to accomplish efficiently when the goal of the study is to exclude pathology with a high degree of confidence.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH TO BRACHIAL PLEXUS MASSES

General Manifestations and Findings

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The imaging appearance of the mass in question will vary with its specific etiology. Solid masses are the most common, and these will vary greatly in enhancement pattern and degree of vascularity and may have regressive changes due to hemorrhage and/or necrosis. Calcification may be present and harder to recognize on MRI than on computed tomography (CT). Some of these masses have well-defined margins, and some will have irregular or infiltrative margins that suggest a malignant or inflammatory (Chapter 166) etiology or some sort of reactive change.

In general, brachial plexus masses will fall into one of two morphologic categories:

- A well-circumscribed mass (Fig. 167.1)

- An infiltrative process with margins that extend beyond the margins of individual roots, trunks, and cords of the plexus (Figs. 167.2 and 167.3)

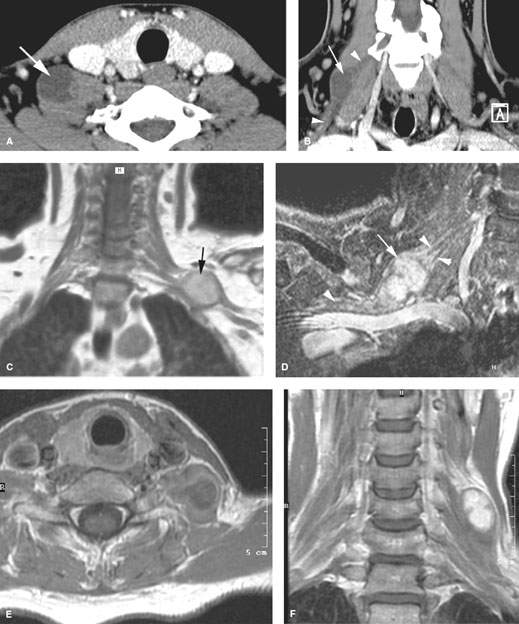

FIGURE 167.1. Five patients with nerve sheath tumors of the brachial plexus. A, B: Patient 1. In (A), the contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography (CT) image shows a hypodense mass lesion (arrow) lateral to but also extending between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. Focal contrast enhancement is seen in the medial part of the mass (arrowhead). In (B), paracoronal reformatted images confirm the presence of a hypodense mass (arrow) between the anterior and middle scalene muscles; the brachial plexus appears somewhat thickened both proximal and distal to the mass (arrowheads). (NOTE: The mass appeared largely cystic during surgery; pathologic examination showed schwannoma with pronounced regressive changes.) C: Patient 2. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) coronal image showing a well-circumscribed mass at the junction of the trunks and cords of the brachial plexus confirmed at surgery to be a schwannoma. D: Patient 3. Fat-suppressed magnetic resonance image done with a localized receiver coil. In this case, the fat suppression is excellent. The schwannoma (arrow) can be seen within and separating the distal trunks and cords of the brachial plexus (arrowheads). E–G: Patient 4 presenting with a lower neck mass and no neurologic deficit. The contrast-enhanced T1W image in (E) shows a well-circumscribed mass within the scalene muscles. In (F), the contrast-enhanced T1W image shows a relatively homogeneously enhancing well-circumscribed mass. In (G), the coronal image shows a very well circumscribed mass in the upper roots of the brachial plexus. This was proven to be a schwannoma. H: Patient 5 presenting with a brachial plexopathy and Horner syndrome. Contrast-enhanced CT suggests that this is due to a mass displacing the carotid artery (arrowhead) and vertebral artery (arrow) in a manner that would imply origin from the inferior cervical ganglion. This proved to be a ganglioneuroma at surgery.

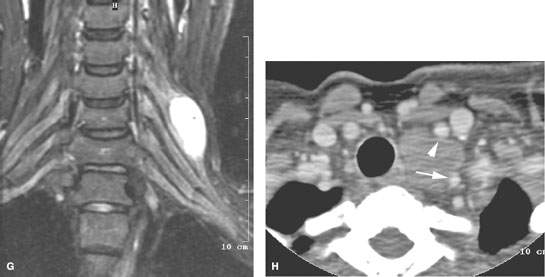

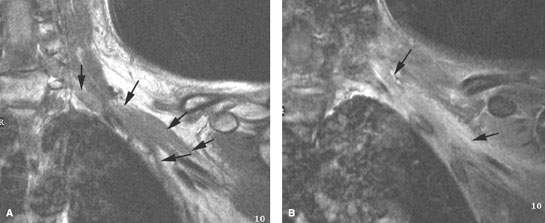

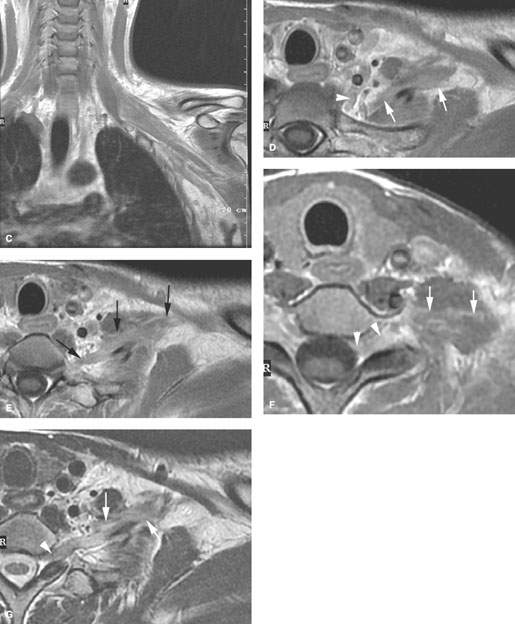

FIGURE 167.2. Two patients with brachial plexopathy secondary to leukemia. A, B: Patient 1. The non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) magnetic resonance (MR) image in (A) shows infiltration of the cords of the brachial plexus (arrows). The T2-weighted (T2W) fat-suppressed image in (B) shows diffusely abnormal signal along the course of the brachial plexus. This was shown to be due to infiltrating acute myelogenous leukemia. (NOTE: The patient’s symptoms resolved with therapy.) C–G: Patient 2 with leukemia presenting with a brachial plexopathy. The MR images all show infiltrating granulocytic sarcoma related to the leukemia (arrows). In (C), the T1W coronal image shows involvement of the brachial plexus from the cords to the divisions along the axillary sheath region. Contrast-enhanced T1W images in (D) show infiltration retrograde to involve the trunks and distal roots (arrows) of the brachial plexus and possibly cervical sympathetic ganglion (arrowhead). In (E), infiltration within the scalene muscle group (arrows) is contiguous with spread along the nerve root sheath toward the thecal sac. In (F), infiltration along the roots (arrows) can be seen entering the epidural space (arrowhead). The T2W image in (G) shows the thickening of one of the lower roots far proximally (arrowhead) as it proceeds from the involved trunk (arrows).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree