Chapter ONE

Chest Radiology

LAURA E. HEYNEMAN CHAPTER EDITOR

CHAPTER EDITOR

LACEY

WASHINGTON

HISTORY

A 26-year-old woman with malaise and night sweats.

FIGURE 1-1A Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows lateralization of the AP reflection, convexity in the AP window, widening of the right paratracheal stripe, and convexity of the azygoesophageal recess. These findings indicate prevascular (anterior mediastinal), AP window, right paratracheal, and subcarinal lymphadenopathy.

FIGURE 1-1A Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows lateralization of the AP reflection, convexity in the AP window, widening of the right paratracheal stripe, and convexity of the azygoesophageal recess. These findings indicate prevascular (anterior mediastinal), AP window, right paratracheal, and subcarinal lymphadenopathy.

FIGURE 1-1B Left lateral chest radiograph confirms increased soft tissue density in the anterior mediastinum and subcarinal regions.

FIGURE 1-1B Left lateral chest radiograph confirms increased soft tissue density in the anterior mediastinum and subcarinal regions.

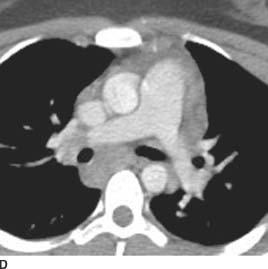

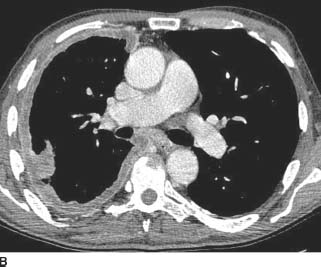

FIGURE 1-1C Contrast-enhanced chest CT (mediastinal window) reveals a conglomerate, lobular anterior mediastinal mass with minimal enhancement.

FIGURE 1-1C Contrast-enhanced chest CT (mediastinal window) reveals a conglomerate, lobular anterior mediastinal mass with minimal enhancement.

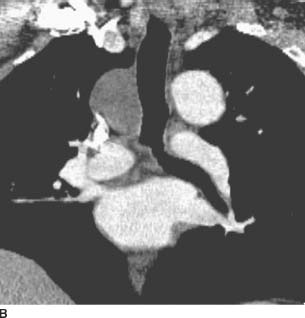

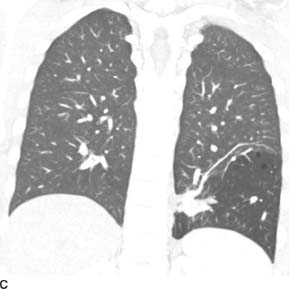

FIGURE 1-1D Contrast-enhanced chest CT (mediastinal window) also reveals enlarged subcarinal and right hilar lymph nodes.

FIGURE 1-1D Contrast-enhanced chest CT (mediastinal window) also reveals enlarged subcarinal and right hilar lymph nodes.

Lymphoma: This is the most likely diagnosis given the age of the patient and associated paratracheal and subcarinal lymphadenopathy.

Lymphoma: This is the most likely diagnosis given the age of the patient and associated paratracheal and subcarinal lymphadenopathy.

Thymoma: This is less likely because these lesions usually occur in older patients, are typically more focal and unilateral, and are not associated with right paratra-cheal or subcarinal lymphadenopathy.

Thymoma: This is less likely because these lesions usually occur in older patients, are typically more focal and unilateral, and are not associated with right paratra-cheal or subcarinal lymphadenopathy.

Germ cell tumor: A primary germ cell tumor of the mediastinum cannot be definitively excluded on the basis of age or radiologic appearance. However, in an adult female patient, teratoma would be the more common germ cell tumor, and there are no features such as calcification or fat within the mass to suggest a teratoma. Malignant germ cell tumors, which are more likely to present as homogeneous soft tissue masses, are much more common in male than female patients.

Germ cell tumor: A primary germ cell tumor of the mediastinum cannot be definitively excluded on the basis of age or radiologic appearance. However, in an adult female patient, teratoma would be the more common germ cell tumor, and there are no features such as calcification or fat within the mass to suggest a teratoma. Malignant germ cell tumors, which are more likely to present as homogeneous soft tissue masses, are much more common in male than female patients.

Metastatic disease: The mediastinum is a common site of metastatic disease from testicular germ cell tumors, renal cell carcinoma, and melanoma. However, the middle mediastinum is often preferentially involved with sparing of the anterior mediastinum, making this a less likely possibility.

Metastatic disease: The mediastinum is a common site of metastatic disease from testicular germ cell tumors, renal cell carcinoma, and melanoma. However, the middle mediastinum is often preferentially involved with sparing of the anterior mediastinum, making this a less likely possibility.

DIAGNOSIS

Hodgkin’s lymphoma

KEY FACTS

Clinical

At least 50% of patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma have intrathoracic lymph node disease.

At least 50% of patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma have intrathoracic lymph node disease.

At least 90% of those with intrathoracic disease have an anterior mediastinal mass. Paratracheal lymph nodes are the second most commonly involved area.

At least 90% of those with intrathoracic disease have an anterior mediastinal mass. Paratracheal lymph nodes are the second most commonly involved area.

Pleural disease is unusual at presentation.

Pleural disease is unusual at presentation.

Radiologic

Hodgkin’s lymphoma typically manifests as a lobulated anterior mediastinal mass that most likely represents matted lymph nodes. Associated mediastinal lymph-adenopathy is common and is a key differentiating feature from thymoma and germ cell tumor.

Hodgkin’s lymphoma typically manifests as a lobulated anterior mediastinal mass that most likely represents matted lymph nodes. Associated mediastinal lymph-adenopathy is common and is a key differentiating feature from thymoma and germ cell tumor.

Intratumoral calcification is rare in patients with untreated lymphoma.

Intratumoral calcification is rare in patients with untreated lymphoma.

Unlike non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma tends to involve contiguous areas, and lung parenchy-mal involvement in the absence of hilar or mediastinal adenopathy is rare before therapy.

Unlike non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma tends to involve contiguous areas, and lung parenchy-mal involvement in the absence of hilar or mediastinal adenopathy is rare before therapy.

SUGGESTED READING

Ansell SM, Armitage JO. Management of Hodgkin lymphoma. Mayo Clin Proc 2006;81:419–426.

Bae YA, Lee KS. Cross-sectional evaluation of thoracic lymphoma. Radiol Clin North Am 2008;46:253–264.

LACEY

WASHINGTON

HISTORY

Asymptomatic 45-year-old woman who had a preoperative chest radiograph obtained prior to cholecystectomy.

FIGURE 1-2A Posteroanterior chest radiograph. There is a right-sided, smoothly marginated mediastinal mass.

FIGURE 1-2A Posteroanterior chest radiograph. There is a right-sided, smoothly marginated mediastinal mass.

FIGURE 1-2B Coronal reformatted image from contrast-enhanced chest CT (mediastinal window) reveals a homogeneous, low-attenuation mass in the right paratracheal region.

FIGURE 1-2B Coronal reformatted image from contrast-enhanced chest CT (mediastinal window) reveals a homogeneous, low-attenuation mass in the right paratracheal region.

Bronchogenic cyst: This is the most likely diagnosis given the location and predominantly cystic appearance.

Bronchogenic cyst: This is the most likely diagnosis given the location and predominantly cystic appearance.

Lymphadenopathy: Low-attenuation paratracheal ade-nopathy can result from central necrosis due to tumor or infection (mycobacterial, fungal). In the setting of tumor, necrotic nodes are most commonly associated with squamous cell primaries. Necrotic nodes are typically more heterogeneous than is the mass in the current case, and may have an enhancing rim.

Lymphadenopathy: Low-attenuation paratracheal ade-nopathy can result from central necrosis due to tumor or infection (mycobacterial, fungal). In the setting of tumor, necrotic nodes are most commonly associated with squamous cell primaries. Necrotic nodes are typically more heterogeneous than is the mass in the current case, and may have an enhancing rim.

DIAGNOSIS

Bronchogenic cyst

KEY FACTS

Clinical

Bronchogenic cysts, also known as foregut malformations, are congenital anomalies caused by abnormal budding of the tracheobronchial tree.

Bronchogenic cysts, also known as foregut malformations, are congenital anomalies caused by abnormal budding of the tracheobronchial tree.

In order to definitively establish bronchogenic origin of a cyst, cartilage should be demonstrated in the wall. In the absence of cartilage in the walls, bronchogenic cysts within the lungs cannot be definitively distinguished from healed abscess cavities, and in the mediastinum, they cannot be definitively distinguished from cysts of esophageal derivation.

In order to definitively establish bronchogenic origin of a cyst, cartilage should be demonstrated in the wall. In the absence of cartilage in the walls, bronchogenic cysts within the lungs cannot be definitively distinguished from healed abscess cavities, and in the mediastinum, they cannot be definitively distinguished from cysts of esophageal derivation.

Bronchogenic cysts are filled with variable amounts of mucus, protein, and cellular debris.

Bronchogenic cysts are filled with variable amounts of mucus, protein, and cellular debris.

A stalk or pedicle commonly attaches the cyst to a mediastinal structure.

A stalk or pedicle commonly attaches the cyst to a mediastinal structure.

Bronchogenic cysts may be associated with other congenital anomalies of lung development such as sequestration, lobar emphysema, and diaphragmatic hernia.

Bronchogenic cysts may be associated with other congenital anomalies of lung development such as sequestration, lobar emphysema, and diaphragmatic hernia.

Bronchogenic cysts are usually asymptomatic but can enlarge and produce symptoms, such as pain, dyspnea, stridor, cough, and respiratory infection, by compression of adjacent mediastinal structures.

Bronchogenic cysts are usually asymptomatic but can enlarge and produce symptoms, such as pain, dyspnea, stridor, cough, and respiratory infection, by compression of adjacent mediastinal structures.

Rare complications include infection, hemorrhage, and carcinoma arising within the cyst.

Rare complications include infection, hemorrhage, and carcinoma arising within the cyst.

Radiologic

Bronchogenic cysts most commonly occur in the sub-carinal and right paratracheal regions.

Bronchogenic cysts most commonly occur in the sub-carinal and right paratracheal regions.

They usually manifest as smooth, well-marginated mediastinal masses on radiographs and CT.

They usually manifest as smooth, well-marginated mediastinal masses on radiographs and CT.

They are typically homogeneous on CT. Approximately, half are of water attenuation and half are of soft tissue attenuation due to intracystic hemorrhage or protein-aceous debris.

They are typically homogeneous on CT. Approximately, half are of water attenuation and half are of soft tissue attenuation due to intracystic hemorrhage or protein-aceous debris.

Bronchogenic cysts that are not of water attenuation may still be characterized as cystic with unenhanced CT if layering milk of calcium is present or on contrast-enhanced CT if they are homogeneous with no central enhancement and a thin wall.

Bronchogenic cysts that are not of water attenuation may still be characterized as cystic with unenhanced CT if layering milk of calcium is present or on contrast-enhanced CT if they are homogeneous with no central enhancement and a thin wall.

Approximately, two-thirds of bronchogenic cysts can be characterized as cystic with CT, based on attenuation, enhancement characteristics, or layering milk of calcium.

Approximately, two-thirds of bronchogenic cysts can be characterized as cystic with CT, based on attenuation, enhancement characteristics, or layering milk of calcium.

On MRI, they are usually of high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Signal intensity on T1-weighted images is variable depending on the presence of hemorrhage or protein (high signal intensity).

On MRI, they are usually of high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Signal intensity on T1-weighted images is variable depending on the presence of hemorrhage or protein (high signal intensity).

Air-fluid levels are rare and are usually due to infection or instrumentation.

Air-fluid levels are rare and are usually due to infection or instrumentation.

SUGGESTED READING

Cioffi U, Bonavina L, De Simone M, et al. Presentation and surgical management of bronchogenic and esophageal duplication cysts in adults. Chest 1998;113:1492–1496.

Fraser RS, Colman N, Muller NL, Pare PD. Fraser and Pare’s Diagnosis of Diseases of the Chest (4th ed). Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co., 1999.

McAdams HP, Kirejczyk WM, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Matsumoto S. Bronchogenic cyst: imaging features with clinical and histopathologic correlation. Radiology 2000;217:441-446.

LACEY

WASHINGTON

HISTORY

A 33-year-old woman with mild upper back pain.

FIGURE 1-3A Posteroanterior chest radiograph with nipple markers. There is a left-sided, smooth, sharply marginated mass in the superior mediastinum. Note that the well-defined borders of the mass extend above the clavicles, indicating that it is in the posterior mediastinum (“cervicothoracic sign”).

FIGURE 1-3A Posteroanterior chest radiograph with nipple markers. There is a left-sided, smooth, sharply marginated mass in the superior mediastinum. Note that the well-defined borders of the mass extend above the clavicles, indicating that it is in the posterior mediastinum (“cervicothoracic sign”).

FIGURE 1-3B Left lateral chest radiograph confirms the posterior location of the mass.

FIGURE 1-3B Left lateral chest radiograph confirms the posterior location of the mass.

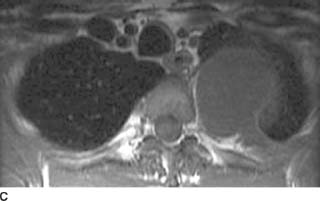

FIGURE 1-3C Tl-weighted axial MR image without intravenous contrast administration reveals a homogeneous, low signal intensity left paraspinal mass with a preserved fat plane between the mass and the adjacent rib.

FIGURE 1-3C Tl-weighted axial MR image without intravenous contrast administration reveals a homogeneous, low signal intensity left paraspinal mass with a preserved fat plane between the mass and the adjacent rib.

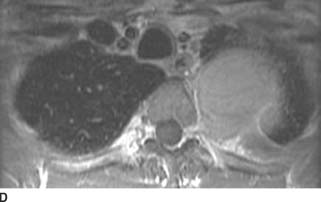

FIGURE 1-3D Tl-weighted axial MR image after intravenous contrast administration reveals diffuse homogeneous enhancement of the left paraspinal mass. There is suggestion of minimal extension of the mass into the left neural foramen.

FIGURE 1-3D Tl-weighted axial MR image after intravenous contrast administration reveals diffuse homogeneous enhancement of the left paraspinal mass. There is suggestion of minimal extension of the mass into the left neural foramen.

Neurogenic tumor: A neurogenic tumor is the most common cause of a posterior mediastinal or paraverte-bral mass. The slight extension of the mass into the left neural foramen would favor this diagnosis.

Neurogenic tumor: A neurogenic tumor is the most common cause of a posterior mediastinal or paraverte-bral mass. The slight extension of the mass into the left neural foramen would favor this diagnosis.

Neuroenteric cyst: These are most commonly associated with vertebral body anomalies such as butterfly vertebrae. On the MR images, the diffuse central enhancement indicates that this mass is solid. Therefore, a neuroenteric cyst is not a viable differential consideration.

Neuroenteric cyst: These are most commonly associated with vertebral body anomalies such as butterfly vertebrae. On the MR images, the diffuse central enhancement indicates that this mass is solid. Therefore, a neuroenteric cyst is not a viable differential consideration.

Paraspinal abscess: This is unlikely in a minimally symptomatic patient without radiologic evidence of vertebral body destruction or disk space narrowing. Additionally, the MR images demonstrate that the mass is solid.

Paraspinal abscess: This is unlikely in a minimally symptomatic patient without radiologic evidence of vertebral body destruction or disk space narrowing. Additionally, the MR images demonstrate that the mass is solid.

Extramedullary hematopoiesis: This usually manifests with bilateral, lobulated paraspinal masses in a patient with severe anemia. The adjacent ribs are often expanded with coarsened trabecula. The absence of these findings and the absence of a history of anemia would make extramedullary hematopoiesis an unlikely diagnosis.

Extramedullary hematopoiesis: This usually manifests with bilateral, lobulated paraspinal masses in a patient with severe anemia. The adjacent ribs are often expanded with coarsened trabecula. The absence of these findings and the absence of a history of anemia would make extramedullary hematopoiesis an unlikely diagnosis.

Lymphoma: Isolated paraspinal disease is an uncommon manifestation of thoracic lymphoma. Patients much more commonly present with additional lymph-adenopathy in the anterior and middle mediastinum.

Lymphoma: Isolated paraspinal disease is an uncommon manifestation of thoracic lymphoma. Patients much more commonly present with additional lymph-adenopathy in the anterior and middle mediastinum.

Metastatic disease: Isolated metastatic disease to the pleura or mediastinum is less likely than a neurogenic tumor given minimal symptoms and no history of a primary malignancy.

Metastatic disease: Isolated metastatic disease to the pleura or mediastinum is less likely than a neurogenic tumor given minimal symptoms and no history of a primary malignancy.

Solitary fibrous tumor of pleura: This is a rare pleu-ral tumor that can manifest as a paraspinal mass and mimic neurogenic tumors. These tumors are often pedunculated, and as a result may shift with differences in patient positioning. The rarity of solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura and the fact that the mass appears to extend slightly into the left neural foramen makes a solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura an unlikely diagnosis.

Solitary fibrous tumor of pleura: This is a rare pleu-ral tumor that can manifest as a paraspinal mass and mimic neurogenic tumors. These tumors are often pedunculated, and as a result may shift with differences in patient positioning. The rarity of solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura and the fact that the mass appears to extend slightly into the left neural foramen makes a solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura an unlikely diagnosis.

DIAGNOSIS

Neurogenic tumor; in this case, a schwannoma

KEY FACTS

Clinical

There are three groups of neurogenic tumors of varying malignant potential: peripheral nerve sheath tumors (schwannomas, neurofibromas, malignant nerve sheath tumors), sympathetic ganglia tumors (neuroblastomas, ganglioneuroblastomas, ganglioneuromas), and, the least common group, tumors of the parasympathetic ganglia or paragangliomas.

There are three groups of neurogenic tumors of varying malignant potential: peripheral nerve sheath tumors (schwannomas, neurofibromas, malignant nerve sheath tumors), sympathetic ganglia tumors (neuroblastomas, ganglioneuroblastomas, ganglioneuromas), and, the least common group, tumors of the parasympathetic ganglia or paragangliomas.

The most common neurogenic tumors in adults are nerve sheath tumors (schwannomas and neurofibromas), while sympathetic ganglia tumors are more common in children.

The most common neurogenic tumors in adults are nerve sheath tumors (schwannomas and neurofibromas), while sympathetic ganglia tumors are more common in children.

Schwannomas and neurofibromas are the most common neurogenic tumors of the posterior mediastinum.

Schwannomas and neurofibromas are the most common neurogenic tumors of the posterior mediastinum.

Patients with schwannomas or neurofibromas can be asymptomatic or present with back pain.

Patients with schwannomas or neurofibromas can be asymptomatic or present with back pain.

Most neurofibromas and schwannomas are solitary and are not associated with neurofibromatosis. However, multiple neurofibromas are usually associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.

Most neurofibromas and schwannomas are solitary and are not associated with neurofibromatosis. However, multiple neurofibromas are usually associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.

Malignant degeneration (malignant nerve sheath tumor) is rare and is most commonly seen in the setting of neurofibromatosis.

Malignant degeneration (malignant nerve sheath tumor) is rare and is most commonly seen in the setting of neurofibromatosis.

Radiologic

The peripheral nerve tumors (schwannomas and neu-rofibromas) manifest as round, paravertebral masses that usually span two vertebral bodies or less. They may invade the neural canal. Rib erosion is common, particularly in neurofibromas.

The peripheral nerve tumors (schwannomas and neu-rofibromas) manifest as round, paravertebral masses that usually span two vertebral bodies or less. They may invade the neural canal. Rib erosion is common, particularly in neurofibromas.

The tumors of the sympathetic ganglia manifest as elongated paraspinal masses, spanning multiple vertebral levels. Intratumoral calcification is common in these tumors.

The tumors of the sympathetic ganglia manifest as elongated paraspinal masses, spanning multiple vertebral levels. Intratumoral calcification is common in these tumors.

On CT, the peripheral nerve tumors manifest as homogeneous, round soft tissue masses that tend to enhance homogeneously. On MR, signal characteristics of the tumors are nonspecific. Most commonly, the masses demonstrate homogeneous signal that is isointense to skeletal muscle on T1-weighted imaging, and mildly heterogeneous high signal on T2-weighted imaging. There tends to be only slight contrast enhancement after intravenous gadolinium administration.

On CT, the peripheral nerve tumors manifest as homogeneous, round soft tissue masses that tend to enhance homogeneously. On MR, signal characteristics of the tumors are nonspecific. Most commonly, the masses demonstrate homogeneous signal that is isointense to skeletal muscle on T1-weighted imaging, and mildly heterogeneous high signal on T2-weighted imaging. There tends to be only slight contrast enhancement after intravenous gadolinium administration.

In large nerves, schwannomas may be differentiated from neurofibromas by the fact that schwannomas tend to be eccentric to the involved nerve. In contrast, the affected nerve in neurofibromas tends to be centrally located or obliterated.

In large nerves, schwannomas may be differentiated from neurofibromas by the fact that schwannomas tend to be eccentric to the involved nerve. In contrast, the affected nerve in neurofibromas tends to be centrally located or obliterated.

The “target sign” has been described for both schwannomas and neurofibromas, and is more common in neurofibromas. This refers to the appearance on T2W imaging in which there is low signal intensity centrally and higher signal intensity peripherally. This corresponds to the histologic finding of central fibrous elements and peripheral myxomatous components. However, the absence of the “target sign” does not preclude the diagnosis of a peripheral nerve sheath tumor.

The “target sign” has been described for both schwannomas and neurofibromas, and is more common in neurofibromas. This refers to the appearance on T2W imaging in which there is low signal intensity centrally and higher signal intensity peripherally. This corresponds to the histologic finding of central fibrous elements and peripheral myxomatous components. However, the absence of the “target sign” does not preclude the diagnosis of a peripheral nerve sheath tumor.

The multiplanar capability and high contrast resolution of MRI may be helpful in demonstrating intracanalicu-lar extension of neurogenic tumors.

The multiplanar capability and high contrast resolution of MRI may be helpful in demonstrating intracanalicu-lar extension of neurogenic tumors.

SUGGESTED READING

Camilla RW, Sameer K, Graham JM, Sisa G. A diagnostic approach to mediastinal abnormalities. Radiographics 2007;27:657–671.

Forsythe A, Volpe J, Muller R. Posterior mediastinal ganglioneuroma. Radiographics 2004;24:594-597.

Tanaka O, Kiryu T, Hirose Y, et al. Neurogenic tumors of the mediastinum and chest wall: MR imaging appearance. J Thorac Imaging 2005;20:316-320.

LACEY

WASHINGTON

HISTORY

A 61-year-old man presents with progressive shortness of breath. A CXR

was performed, followed by thoracentesis and contrast-enhanced CT of the chest.

FIGURE 1-4A Posteroanterior chest radiograph. There is a lobulated soft tissue mass surrounding the right hemithorax with mild mass effect on the trachea. Several poorly defined opacities project over the lateral left hemithorax.

FIGURE 1-4A Posteroanterior chest radiograph. There is a lobulated soft tissue mass surrounding the right hemithorax with mild mass effect on the trachea. Several poorly defined opacities project over the lateral left hemithorax.

FIGURE 1-4B Contrast-enhanced chest CT (mediastinal window) demonstrates enhancing nodular pleural soft tissue encasing the right lung. There is also a component of loculated right pleural effusion. There is suggestion of subcarinal lymphadenopathy. Several calcified pleural plaques are seen in the left hemithorax.

FIGURE 1-4B Contrast-enhanced chest CT (mediastinal window) demonstrates enhancing nodular pleural soft tissue encasing the right lung. There is also a component of loculated right pleural effusion. There is suggestion of subcarinal lymphadenopathy. Several calcified pleural plaques are seen in the left hemithorax.

FIGURE 1-4C Coronal reformat of contrast-enhanced CT (mediastinal window) confirms the circumferential right pleural nodularity, pleural enhancement, and loculated right pleural effusion. There is extension of the right pleural soft tissue into the right superolateral chest wall. A calcified right diaphragmatic pleural plaque and a calcified pleural plaque within the lateral left hemithorax are also present.

FIGURE 1-4C Coronal reformat of contrast-enhanced CT (mediastinal window) confirms the circumferential right pleural nodularity, pleural enhancement, and loculated right pleural effusion. There is extension of the right pleural soft tissue into the right superolateral chest wall. A calcified right diaphragmatic pleural plaque and a calcified pleural plaque within the lateral left hemithorax are also present.

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM): This is the most likely diagnosis given the age of the patient, the radiologic appearance of the pleura, and the evidence of prior asbestos exposure (pleural plaques).

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM): This is the most likely diagnosis given the age of the patient, the radiologic appearance of the pleura, and the evidence of prior asbestos exposure (pleural plaques).

Pleural metastatic disease: Metastatic disease is the most common malignancy of the pleura. However, the appearance of circumferential pleural thickening, in some areas >1 cm in thickness, and a tumor rind with mediastinal pleural involvement is more suggestive of mesothelioma than metastases, particularly in a patient with bilateral pleural calcifications.

Pleural metastatic disease: Metastatic disease is the most common malignancy of the pleura. However, the appearance of circumferential pleural thickening, in some areas >1 cm in thickness, and a tumor rind with mediastinal pleural involvement is more suggestive of mesothelioma than metastases, particularly in a patient with bilateral pleural calcifications.

Loculated empyema: This patient had no signs or symptoms of empyema. The degree of pleural thickening argues for a neoplastic process, making empyema a less likely possibility.

Loculated empyema: This patient had no signs or symptoms of empyema. The degree of pleural thickening argues for a neoplastic process, making empyema a less likely possibility.

DIAGNOSIS

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM)

KEY FACTS

Clinical

Mesothelioma is rare. Its incidence has peaked in the United States but continues to rise in Europe due to continued asbestos use in the 1970s.

Mesothelioma is rare. Its incidence has peaked in the United States but continues to rise in Europe due to continued asbestos use in the 1970s.

There is a high association with prior asbestos exposure, but no exposure history is found in up to 20% of cases. There is a long latency period, with the tumor occurring up to 50 years following asbestos exposure.

There is a high association with prior asbestos exposure, but no exposure history is found in up to 20% of cases. There is a long latency period, with the tumor occurring up to 50 years following asbestos exposure.

Patients may present with increasing dyspnea or chest pain, commonly in the sixth to seventh decade of life, and mesothelioma should be considered in any patient who presents with chest pain and either a history of asbestos exposure or unilateral radiographic pleural abnormalities.

Patients may present with increasing dyspnea or chest pain, commonly in the sixth to seventh decade of life, and mesothelioma should be considered in any patient who presents with chest pain and either a history of asbestos exposure or unilateral radiographic pleural abnormalities.

There are three histologic subtypes—epithelial, sarcomatous, and mixed—and while overall prognosis is poor, the epithelial subtype is associated with a somewhat better prognosis.

There are three histologic subtypes—epithelial, sarcomatous, and mixed—and while overall prognosis is poor, the epithelial subtype is associated with a somewhat better prognosis.

There is no relationship with smoking.

There is no relationship with smoking.

Extrapleural pneumonectomy may be considered in which the lung and all the parietal pleura, pericardium, and diaphragm are removed.

Extrapleural pneumonectomy may be considered in which the lung and all the parietal pleura, pericardium, and diaphragm are removed.

Radiologic

At CT, circumferential pleural thickening, nodular pleural thickening, mediastinal pleural involvement, and possibly pleural thickening >1 cm are suggestive of pleural malignancy with a fairly high positive predictive value; the absence of these findings, however, does not exclude pleural malignancy.

At CT, circumferential pleural thickening, nodular pleural thickening, mediastinal pleural involvement, and possibly pleural thickening >1 cm are suggestive of pleural malignancy with a fairly high positive predictive value; the absence of these findings, however, does not exclude pleural malignancy.

Rind-like pleural involvement, mediastinal pleural involvement, and pleural thickness >1 cm favor meso-thelioma over metastatic pleural disease.

Rind-like pleural involvement, mediastinal pleural involvement, and pleural thickness >1 cm favor meso-thelioma over metastatic pleural disease.

Pleural fluid is usually seen at the time of presentation.

Pleural fluid is usually seen at the time of presentation.

Contralateral pleural plaques from prior asbestos exposure may be identified.

Contralateral pleural plaques from prior asbestos exposure may be identified.

Local invasion of the chest wall, mediastinum, or diaphragm is common. Chest wall involvement is commonly seen at the site of previous interventions including biopsy and drain sites.

Local invasion of the chest wall, mediastinum, or diaphragm is common. Chest wall involvement is commonly seen at the site of previous interventions including biopsy and drain sites.

If surgical resection is being considered, CT imaging should be extended to the level of the third lumbar vertebra with reformatted sagittal and coronal images to better assess for chest wall and intra-abdominal extension.

If surgical resection is being considered, CT imaging should be extended to the level of the third lumbar vertebra with reformatted sagittal and coronal images to better assess for chest wall and intra-abdominal extension.

Lymphadenopathy occurs with more extensive tumor and in the later stages of disease.

Lymphadenopathy occurs with more extensive tumor and in the later stages of disease.

Contralateral lung or brain metastases are unusual features.

Contralateral lung or brain metastases are unusual features.

SUGGESTED READING

Benamore RE, O’Doherty MJ, Entwisle JJ. Use of imaging in the management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Clin Radiol 2005;60: 1237–1247.

Gottschall EB. Occupational and environmental thoracic malignancies. J Thorac Imaging 2002;17:189-197.

Metintas M, Ucgun I, Elbek O, et al. Computed tomography features in malignant pleural mesothelioma and other commonly seen pleural diseases. Eur J Radiol 2002;41:1-9.

Seely JM, Nguyen ET, Churg AM, Muller NL. Malignant pleural mesothe-lioma: computed tomography and correlation with histology. Eur J Radiol 2009;70:485-491.

LAURA E. HEYNEMAN

HISTORY

An otherwise healthy 25-year-old woman with a history of recurrent left lower lobe pneumonias who presents with fever, cough, and chest pain.

FIGURES 1-5A and 1-5B Posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs reveal minimal opacity in the medial posterior left lung base; the opacity is best seen on the lateral view (“positive spine sign”).

FIGURES 1-5A and 1-5B Posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs reveal minimal opacity in the medial posterior left lung base; the opacity is best seen on the lateral view (“positive spine sign”).

FIGURE 1-5C Coronal reformat from contrast-enhanced chest CT (lung window) reveals hyperinflation and hyperlucency within the left lower lobe. There are tiny focal air cysts. Additionally, there is a tubular, branching opacity that extends from midline and likely represents the opacity seen on the radiographs. On other images, this tubular opacity connects to the abdominal aorta.

FIGURE 1-5C Coronal reformat from contrast-enhanced chest CT (lung window) reveals hyperinflation and hyperlucency within the left lower lobe. There are tiny focal air cysts. Additionally, there is a tubular, branching opacity that extends from midline and likely represents the opacity seen on the radiographs. On other images, this tubular opacity connects to the abdominal aorta.

FIGURE 1-5D Oblique sagittal maximum intensity projection image from contrast-enhanced spiral CT (mediastinal window) demonstrates an anomalous vessel arising from the distal thoracic aorta. This vessel supplies the hyperlucent segment in the left lower lobe.

FIGURE 1-5D Oblique sagittal maximum intensity projection image from contrast-enhanced spiral CT (mediastinal window) demonstrates an anomalous vessel arising from the distal thoracic aorta. This vessel supplies the hyperlucent segment in the left lower lobe.

Intralobar sequestration (ILS): This is the most likely diagnosis given the history of recurrent pneumonia, the hyperlucency of the left lower lobe, and the radiologic demonstration of a systemic vascular supply to the left lower lobe.

Intralobar sequestration (ILS): This is the most likely diagnosis given the history of recurrent pneumonia, the hyperlucency of the left lower lobe, and the radiologic demonstration of a systemic vascular supply to the left lower lobe.

Postobstructive pneumonia: This is a consideration when a patient has recurrent infections in the same distribution. An endobronchial lesion from an aspirated foreign body or an indolent neoplasm such as a hamar-toma or carcinoid tumor is a consideration in a young individual.

Postobstructive pneumonia: This is a consideration when a patient has recurrent infections in the same distribution. An endobronchial lesion from an aspirated foreign body or an indolent neoplasm such as a hamar-toma or carcinoid tumor is a consideration in a young individual.

Recurrent aspiration: While aspiration may recur in the dependent lung, this is unlikely in an otherwise healthy young woman in whom there are no risk factors for aspiration.

Recurrent aspiration: While aspiration may recur in the dependent lung, this is unlikely in an otherwise healthy young woman in whom there are no risk factors for aspiration.

Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM): Although the location and appearance of the lesion is consistent with this diagnosis, CCAM is very rarely diagnosed in adults.

Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM): Although the location and appearance of the lesion is consistent with this diagnosis, CCAM is very rarely diagnosed in adults.

DIAGNOSIS

Intralobar sequestration (ILS)

KEY FACTS

Clinical

A sequestration is defined as a malformation of pulmonary tissue characterized by lack of communication with the tracheobronchial tree as well as systemic arterial supply. There are two types of sequestration: ILS and extralobar sequestration (ELS).

A sequestration is defined as a malformation of pulmonary tissue characterized by lack of communication with the tracheobronchial tree as well as systemic arterial supply. There are two types of sequestration: ILS and extralobar sequestration (ELS).

Both types of sequestration lack a normal connection to the tracheobronchial tree. ELS is contained within its own pleura and has systemic venous drainage into the right atrium. In contrast, ILS has normal pulmonary venous drainage and is not enveloped in its own pleura.

Both types of sequestration lack a normal connection to the tracheobronchial tree. ELS is contained within its own pleura and has systemic venous drainage into the right atrium. In contrast, ILS has normal pulmonary venous drainage and is not enveloped in its own pleura.

ILS is much more common than ELS, and accounts for 75% of bronchopulmonary sequestrations.

ILS is much more common than ELS, and accounts for 75% of bronchopulmonary sequestrations.

ILS may be an acquired abnormality due to recurrent infections with secondary bronchial obstruction and recruitment of systemic arteries.

ILS may be an acquired abnormality due to recurrent infections with secondary bronchial obstruction and recruitment of systemic arteries.

ILS usually occurs in the posterior or medial basilar segments of the lower lobes, left greater than right (3 to 2).

ILS usually occurs in the posterior or medial basilar segments of the lower lobes, left greater than right (3 to 2).

ILS typically manifests in young patients with signs and symptoms of recurrent pneumonia.

ILS typically manifests in young patients with signs and symptoms of recurrent pneumonia.

ELS is often associated with other congenital anomalies and is usually diagnosed within the first 6 months of life.

ELS is often associated with other congenital anomalies and is usually diagnosed within the first 6 months of life.

Radiologic

On radiographs, ILS commonly manifests as focal parenchymal consolidation. Cystic changes and air-fluid levels are also common.

On radiographs, ILS commonly manifests as focal parenchymal consolidation. Cystic changes and air-fluid levels are also common.

Other, less common, manifestations include a focal mass or a hyperlucent segment.

Other, less common, manifestations include a focal mass or a hyperlucent segment.

By CT, MRI, or ultrasound, ILS usually manifests as a unilocular or multilocular cystic mass. Solid masses are sometimes seen.

By CT, MRI, or ultrasound, ILS usually manifests as a unilocular or multilocular cystic mass. Solid masses are sometimes seen.

The systemic arterial supply to both ILS and ELS usually arises from the abdominal or thoracic aorta but may originate from lumbar arteries or the celiac axis. Venous drainage of ILS is usually via an inferior pulmonary vein.

The systemic arterial supply to both ILS and ELS usually arises from the abdominal or thoracic aorta but may originate from lumbar arteries or the celiac axis. Venous drainage of ILS is usually via an inferior pulmonary vein.

Diagnosis of ILS is made by radiologic demonstration of systemic vascular supply. This can be accomplished with angiography, contrast-enhanced CT (ideally performed as a CT angiogram), or MRI.

Diagnosis of ILS is made by radiologic demonstration of systemic vascular supply. This can be accomplished with angiography, contrast-enhanced CT (ideally performed as a CT angiogram), or MRI.

SUGGESTED READING

Berrocal T, Madrid C, Novo S, et al. Congenital anomalies of the tracheobronchial tree, lung, and mediastinum: embryology, radiology, and pathology. Radiographics 2004;24:e17.

Bolca N, Topal U, Bayram S. Bronchopulmonary sequestration: radiologic flndings. Eur J Radiol 2004;52:185-191.

Lee EY, Boiselle PM, Cleveland RH. Multidetector CT evaluation of congenital lung anomalies. Radiology 2008;247:632-648.

LAURA E. HEYNEMAN

HISTORY

A 35-year-old male with no past medical history, who presents with cough and hemoptysis.

FIGURE 1-6A Frontal scout image from CT scan reveals a homogeneous opacity with sharply demarcated lateral border within the medial inferior right hemithorax. The right hilum is small and inferiorly displaced, and there is mediastinal shift to the right. Additionally, the right heart border is obscured and there is apparent elevation of the right hemidiaphragm. The findings are consistent with combined right lower lobe and middle lobe collapse.

FIGURE 1-6A Frontal scout image from CT scan reveals a homogeneous opacity with sharply demarcated lateral border within the medial inferior right hemithorax. The right hilum is small and inferiorly displaced, and there is mediastinal shift to the right. Additionally, the right heart border is obscured and there is apparent elevation of the right hemidiaphragm. The findings are consistent with combined right lower lobe and middle lobe collapse.

FIGURE 1-6B Axial image from a noncontrasted CT (mediastinal window) reveals a right hilar mass that contains a punctate calcification. The mass obliterates the bronchus interme-dius, with only a tiny focus of air remaining within the bronchus.

FIGURE 1-6B Axial image from a noncontrasted CT (mediastinal window) reveals a right hilar mass that contains a punctate calcification. The mass obliterates the bronchus interme-dius, with only a tiny focus of air remaining within the bronchus.

FIGURE 1-6C Axial image from the noncontrasted CT (mediastinal window) confirms the right middle and lower lobe collapse due to the more proximal bronchial obstruction.

FIGURE 1-6C Axial image from the noncontrasted CT (mediastinal window) confirms the right middle and lower lobe collapse due to the more proximal bronchial obstruction.

Bronchial carcinoid tumor: This is the best single diagnosis given the radiologic appearance and the age of the patient.

Bronchial carcinoid tumor: This is the best single diagnosis given the radiologic appearance and the age of the patient.

Lung cancer: Although lung cancer cannot be excluded, it is less likely in a patient of this age.

Lung cancer: Although lung cancer cannot be excluded, it is less likely in a patient of this age.

Lymphoma: Bronchial obstruction is a relatively uncommon manifestation of lymphoma, and a hilar mass without lymphadenopathy elsewhere in the mediastinum would also be an unusual presentation.

Lymphoma: Bronchial obstruction is a relatively uncommon manifestation of lymphoma, and a hilar mass without lymphadenopathy elsewhere in the mediastinum would also be an unusual presentation.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma: This tumor is also a possible diagnosis; however, these tumors are much less common than carcinoid tumors. They occur in the trachea and bronchi with equal frequency but, because tracheal tumors are generally less common than bronchial tumors, adenoid cystic carcinomas represent a larger percentage of tracheal tumors than of bronchial tumors.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma: This tumor is also a possible diagnosis; however, these tumors are much less common than carcinoid tumors. They occur in the trachea and bronchi with equal frequency but, because tracheal tumors are generally less common than bronchial tumors, adenoid cystic carcinomas represent a larger percentage of tracheal tumors than of bronchial tumors.

Mucoepidermoid cancer: This tumor is also a differential consideration, but is extremely rare.

Mucoepidermoid cancer: This tumor is also a differential consideration, but is extremely rare.

Endobronchial metastasis: Endobronchial metasta-ses from a lung, breast, renal, melanoma, or colonic primary can occur, but are unlikely in a young patient without a known history of a primary malignancy.

Endobronchial metastasis: Endobronchial metasta-ses from a lung, breast, renal, melanoma, or colonic primary can occur, but are unlikely in a young patient without a known history of a primary malignancy.

DIAGNOSIS

Bronchial carcinoid tumor

KEY FACTS

Clinical

Eighty-five percent of carcinoid tumors occur within the central bronchi (central carcinoid); 15% arise distal to segmental bronchi (peripheral carcinoid).

Eighty-five percent of carcinoid tumors occur within the central bronchi (central carcinoid); 15% arise distal to segmental bronchi (peripheral carcinoid).

Peripheral tumors manifest as asymptomatic pulmonary nodules.

Peripheral tumors manifest as asymptomatic pulmonary nodules.

Central tumors manifest with symptoms of bronchial obstruction such as hemoptysis, chest pain, or recurrent pneumonia.

Central tumors manifest with symptoms of bronchial obstruction such as hemoptysis, chest pain, or recurrent pneumonia.

Bronchial carcinoid tumors are only rarely associated with paraneoplastic syndromes such as Cushing’s syndrome, carcinoid syndrome, or acromegaly. Only 2% of patients with bronchopulmonary carcinoid have Cush-ing’s syndrome from ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) production.

Bronchial carcinoid tumors are only rarely associated with paraneoplastic syndromes such as Cushing’s syndrome, carcinoid syndrome, or acromegaly. Only 2% of patients with bronchopulmonary carcinoid have Cush-ing’s syndrome from ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) production.

Carcinoids are histologically divided into two types: typical (75% to 90%) and atypical (10% to 25%). Prognosis depends on the histologic subtype as well as on nodal status and tumor size.

Carcinoids are histologically divided into two types: typical (75% to 90%) and atypical (10% to 25%). Prognosis depends on the histologic subtype as well as on nodal status and tumor size.

The prognosis for typical carcinoid tumors is excellent even with hilar or ipsilateral mediastinal lymph node metastases. The prognosis for atypical carcinoid tumors is less favorable.

Radiologic

Peripheral tumors manifest as solitary, well-circumscribed pulmonary nodules.

Peripheral tumors manifest as solitary, well-circumscribed pulmonary nodules.

Central lesions manifest as hilar masses with or without obstructive atelectasis or pneumonia. Other potential manifestations of central obstruction include air trapping and mucoid impaction.

Central lesions manifest as hilar masses with or without obstructive atelectasis or pneumonia. Other potential manifestations of central obstruction include air trapping and mucoid impaction.

In some cases, a small endobronchial component is associated with a larger exobronchial component. This is termed the “tip-of-the-iceberg” sign.

In some cases, a small endobronchial component is associated with a larger exobronchial component. This is termed the “tip-of-the-iceberg” sign.

Calcifications, which may be eccentric, punctate, or coarse, are seen by CT in up to 26% of cases. Diffuse calcification may be seen and simulate broncholithiasis.

Calcifications, which may be eccentric, punctate, or coarse, are seen by CT in up to 26% of cases. Diffuse calcification may be seen and simulate broncholithiasis.

Carcinoids are characteristically highly vascular, and enhance intensely when intravenous contrast is administered. However, the absence of intense enhancement does not preclude the diagnosis of carcinoid, and the degree of contrast enhancement cannot be used to differentiate bronchial carcinoid from bronchogenic carcinoma.

Carcinoids are characteristically highly vascular, and enhance intensely when intravenous contrast is administered. However, the absence of intense enhancement does not preclude the diagnosis of carcinoid, and the degree of contrast enhancement cannot be used to differentiate bronchial carcinoid from bronchogenic carcinoma.

On T2-weighted MR images, bronchial carcinoid tumors have a very high signal intensity.

On T2-weighted MR images, bronchial carcinoid tumors have a very high signal intensity.

In the few patients who have symptoms of ectopic ACTH production, octreotide scintigraphy is positive. The octreotide scans are particularly helpful when the tumors are small (<1 cm) and relatively inconspicuous on cross-sectional imaging.

In the few patients who have symptoms of ectopic ACTH production, octreotide scintigraphy is positive. The octreotide scans are particularly helpful when the tumors are small (<1 cm) and relatively inconspicuous on cross-sectional imaging.

Radiologic manifestations of typical and atypical carci-noids are similar. Atypical carcinoids tend to be larger, more peripheral, and more necrotic than the typical variant, but this is quite variable.

Radiologic manifestations of typical and atypical carci-noids are similar. Atypical carcinoids tend to be larger, more peripheral, and more necrotic than the typical variant, but this is quite variable.

SUGGESTED READING

Bertino EM, Confer PD, Colonna JE, et al. Pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors: a review article. Cancer 2009;115:4434–4441.

Chong S, Lee KS, Chung MJ, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: clinical, pathologic, and imaging findings. Radiographics 2006;26:41–57.

Scarsbrook AF, Ganeshan A, Statham J, et al. Anatomic and functional imaging of metastatic carcinoid tumors. Radiographics 2007;27:455-477.

LAURA E. HEYNEMAN

HISTORY

A 35-year-old woman with a long history of sinus disease presents with sudden onset of cough, fever, and hemoptysis.

FIGURE 1-7A Posteroanterior chest radiograph. There are bilateral, mid lung cavitary nodules with an air-fluid level noted within a right perihilar nodule. A nodular opacity over the right anterior first rib may represent an additional subtle pulmonary nodule.

FIGURE 1-7A Posteroanterior chest radiograph. There are bilateral, mid lung cavitary nodules with an air-fluid level noted within a right perihilar nodule. A nodular opacity over the right anterior first rib may represent an additional subtle pulmonary nodule.

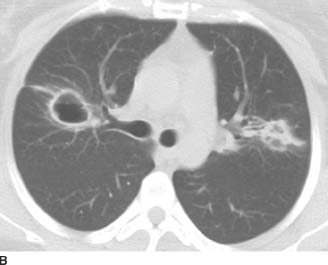

FIGURE 1-7B Chest CT (lung window) performed 2 weeks later reveals a thin-walled cavity within the right upper lobe with an adjacent linear focus that may represent subsegmental atelectasis. There is a nodular opacity within the left upper lobe with suggestion of central lucency.

FIGURE 1-7B Chest CT (lung window) performed 2 weeks later reveals a thin-walled cavity within the right upper lobe with an adjacent linear focus that may represent subsegmental atelectasis. There is a nodular opacity within the left upper lobe with suggestion of central lucency.

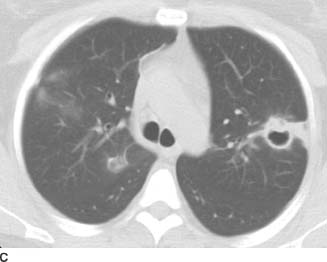

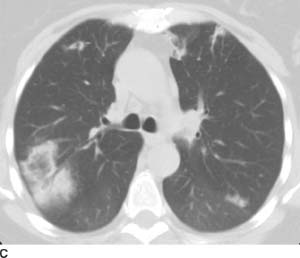

FIGURE 1-7C Image from the same chest CT (lung window) confirms the cavitation within the left upper lobe nodule. The nodule has an eccentric focus of soft tissue anteriorly, and there is a small amount of consolidation peripheral to the nodule. Additionally, there are scattered foci of ground glass within the right upper lobe, some of which are somewhat nodular in configuration. The patient has undergone right upper lobe wedge resection, with a suture line noted in the medial right upper lobe.

FIGURE 1-7C Image from the same chest CT (lung window) confirms the cavitation within the left upper lobe nodule. The nodule has an eccentric focus of soft tissue anteriorly, and there is a small amount of consolidation peripheral to the nodule. Additionally, there are scattered foci of ground glass within the right upper lobe, some of which are somewhat nodular in configuration. The patient has undergone right upper lobe wedge resection, with a suture line noted in the medial right upper lobe.

Vasculitis: Potential vasculitic etiologies include Wegen-er’s granulomatosis and, much less likely, cavitary rheumatoid nodules. Since rheumatoid nodules tend to be a late manifestation of the disease, and the nodules tend to wax-and-wane with the course of subcutaneous nodules, the absence of a known history of rheumatoid arthritis would make this diagnosis unlikely. However, the given history of chronic sinus disease makes Wegener’s granulomatosis a very likely diagnosis.

Vasculitis: Potential vasculitic etiologies include Wegen-er’s granulomatosis and, much less likely, cavitary rheumatoid nodules. Since rheumatoid nodules tend to be a late manifestation of the disease, and the nodules tend to wax-and-wane with the course of subcutaneous nodules, the absence of a known history of rheumatoid arthritis would make this diagnosis unlikely. However, the given history of chronic sinus disease makes Wegener’s granulomatosis a very likely diagnosis.

Infection: Given that the patient is febrile, an atypical infection must be considered. Infectious differential considerations for cavitary nodules include fungi such as angioinvasive aspergillosis or coccidiomycosis, nocardia, anaerobes and gram-negative bacteria, and septic emboli. The absence of a travel history or an immunocompromised status would make opportunistic infections and fungal infections less likely. Furthermore, the given history of chronic sinus disease would not be pertinent for a diagnosis of an acute infection.

Infection: Given that the patient is febrile, an atypical infection must be considered. Infectious differential considerations for cavitary nodules include fungi such as angioinvasive aspergillosis or coccidiomycosis, nocardia, anaerobes and gram-negative bacteria, and septic emboli. The absence of a travel history or an immunocompromised status would make opportunistic infections and fungal infections less likely. Furthermore, the given history of chronic sinus disease would not be pertinent for a diagnosis of an acute infection.

Neoplasm: Potential neoplastic etiologies for cavitary nodules include synchronous primary lung cancers (squamous cell carcinoma), metastatic disease, or less likely, cavitary parenchymal lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease). Tumors that cavitate after metastasizing to the lung include squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, and metastatic sarcoma. However, the absence of a known primary malignancy would make the diagnosis of metastases unlikely. Furthermore, the presence of fever and the acute onset of the patient’s symptoms would be unusual in the setting of malignancy.

Neoplasm: Potential neoplastic etiologies for cavitary nodules include synchronous primary lung cancers (squamous cell carcinoma), metastatic disease, or less likely, cavitary parenchymal lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease). Tumors that cavitate after metastasizing to the lung include squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, and metastatic sarcoma. However, the absence of a known primary malignancy would make the diagnosis of metastases unlikely. Furthermore, the presence of fever and the acute onset of the patient’s symptoms would be unusual in the setting of malignancy.

DIAGNOSIS

Wegener’s granulomatosis

KEY FACTS

Clinical

Wegener’s granulomatosis is a multisystem granuloma-tous vasculitis.

Wegener’s granulomatosis is a multisystem granuloma-tous vasculitis.

Major sites of involvement include the sinonasal cavity, lungs, and kidneys.

Major sites of involvement include the sinonasal cavity, lungs, and kidneys.

Elevated c-ANCA (antineutrophil cytoplasm antibody) titers are sensitive and specific for active Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Elevated c-ANCA (antineutrophil cytoplasm antibody) titers are sensitive and specific for active Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Wegener’s granulomatosis has a good prognosis with aggressive medical management.

Wegener’s granulomatosis has a good prognosis with aggressive medical management.

Radiologic

Patients typically present with multiple pulmonary nodules or masses, but the nodules may be solitary. One-third to one-half of nodules cavitate, particularly, when the nodules are >2 cm in diameter. The cavity walls may be thin and smooth or thick and nodular.

Patients typically present with multiple pulmonary nodules or masses, but the nodules may be solitary. One-third to one-half of nodules cavitate, particularly, when the nodules are >2 cm in diameter. The cavity walls may be thin and smooth or thick and nodular.

An air-fluid level may be present within a Wegener’s cavity, although the presence of an air-fluid level does raise the possibility of superimposed infection. Similarly, new pulmonary opacities in a patient being treated for known Wegener’s granulomatosis suggest opportunistic infection, either fungal or Pneumocystis jiovecii pneumonia (PCP).

An air-fluid level may be present within a Wegener’s cavity, although the presence of an air-fluid level does raise the possibility of superimposed infection. Similarly, new pulmonary opacities in a patient being treated for known Wegener’s granulomatosis suggest opportunistic infection, either fungal or Pneumocystis jiovecii pneumonia (PCP).

The disease can also manifest as focal or diffuse paren-chymal consolidation. Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage is the presenting manifestation in up to 10% of cases.

The disease can also manifest as focal or diffuse paren-chymal consolidation. Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage is the presenting manifestation in up to 10% of cases.

Involvement of the trachea and bronchi occurs as a late complication in 15% to 25% of patients and can result in lobar atelectasis and bronchial stenoses.

Involvement of the trachea and bronchi occurs as a late complication in 15% to 25% of patients and can result in lobar atelectasis and bronchial stenoses.

Pleural effusions are uncommon and adenopathy is rare.

Pleural effusions are uncommon and adenopathy is rare.

SUGGESTED READING

Allen SD, Harvey CJ. Imaging of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Br J Radiol 2007;80:757–765.

Ananthakrishnan L, Sharma N, Kanne J. Wegener’s granulomatosis in the chest: high-resolution CT findings. Am J Roentgenol 2009;192:676-682.

LAURA E. HEYNEMAN

HISTORY

A 25-year-old man with progressive dyspnea.

FIGURE 1-8A Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows bilateral 3- to 5-mm nodular and reticular opacities within the upper lobes. The lung volumes are normal. There is no lymphadenopathy or pleural abnormality.

FIGURE 1-8A Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows bilateral 3- to 5-mm nodular and reticular opacities within the upper lobes. The lung volumes are normal. There is no lymphadenopathy or pleural abnormality.

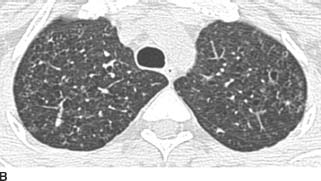

FIGURES 1-8B, 1-8C, and 1-8D HRCT images (lung window) show multiple upper lobe air cysts and scattered small nodules (B and C). A few of the nodules demonstrate central lucencies. The process spares the lung bases and costophrenic angles (D).

FIGURES 1-8B, 1-8C, and 1-8D HRCT images (lung window) show multiple upper lobe air cysts and scattered small nodules (B and C). A few of the nodules demonstrate central lucencies. The process spares the lung bases and costophrenic angles (D).

Chest radiograph: Differential diagnosis based on the radiograph, includes sarcoidosis, pulmonary histiocytosis X (PHX), infection such as tuberculosis (TB) or disseminated fungal infection, pneumoconiosis (silicosis or coal worker’s pneumoconiosis), and hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP).

Chest radiograph: Differential diagnosis based on the radiograph, includes sarcoidosis, pulmonary histiocytosis X (PHX), infection such as tuberculosis (TB) or disseminated fungal infection, pneumoconiosis (silicosis or coal worker’s pneumoconiosis), and hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP).

High-resolution CT (HRCT)—nodules: Differential diagnosis for centrilobular (CL) nodules on HRCT includes sarcoidosis, PHX, HP, pneumoconiosis, TB, and various forms of bronchiolitis.

High-resolution CT (HRCT)—nodules: Differential diagnosis for centrilobular (CL) nodules on HRCT includes sarcoidosis, PHX, HP, pneumoconiosis, TB, and various forms of bronchiolitis.

HRCT—air cysts: Differential diagnosis for air cysts or ring lucencies on HRCT includes lymphangioleiomyo-matosis, PHX, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP), bronchiectasis, and “honeycomb” lung (idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [IPF]). Additionally, small nodules with central cavitation (“cheerio sign”) may be seen with bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma (BAC).

HRCT—air cysts: Differential diagnosis for air cysts or ring lucencies on HRCT includes lymphangioleiomyo-matosis, PHX, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP), bronchiectasis, and “honeycomb” lung (idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [IPF]). Additionally, small nodules with central cavitation (“cheerio sign”) may be seen with bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma (BAC).

The combination of upper lobe predominant nodules and ring lucencies on HRCT makes PHX the most likely diagnosis.

The combination of upper lobe predominant nodules and ring lucencies on HRCT makes PHX the most likely diagnosis.

DIAGNOSIS

Pulmonary histiocytosis X

KEY FACTS

Clinical

Also known as Langerhans cell histiocytosis or eosino-philic granuloma of lung.

Also known as Langerhans cell histiocytosis or eosino-philic granuloma of lung.

Patients are typically young to middle aged, with a higher incidence in men.

Patients are typically young to middle aged, with a higher incidence in men.

Patients typically present with cough and dyspnea. Twenty percent present with a spontaneous pneumothorax.

Patients typically present with cough and dyspnea. Twenty percent present with a spontaneous pneumothorax.

Almost all patients (at least 90%) with PHX are cigarette smokers.

Almost all patients (at least 90%) with PHX are cigarette smokers.

Radiologic

Typical radiographic manifestations include nodular or reticulonodular opacities in the mid- and upper-lung zones. Lung volumes are typically normal or increased. Adenopathy and pleural effusion are uncommon. A pneumothorax may be evident.

Typical radiographic manifestations include nodular or reticulonodular opacities in the mid- and upper-lung zones. Lung volumes are typically normal or increased. Adenopathy and pleural effusion are uncommon. A pneumothorax may be evident.

Early PHX manifests on HRCT as 3- to 5-mm nodules that are predominantly CL in distribution. The nodules may develop central cavitation, and eventually evolve into thick- and thin-walled air cysts. The cysts may coalesce into unusual shapes. Both cysts and nodules are more common in the mid- to upper-lung zones, and typically spare the costophrenic angles.

Early PHX manifests on HRCT as 3- to 5-mm nodules that are predominantly CL in distribution. The nodules may develop central cavitation, and eventually evolve into thick- and thin-walled air cysts. The cysts may coalesce into unusual shapes. Both cysts and nodules are more common in the mid- to upper-lung zones, and typically spare the costophrenic angles.

The combination of air cysts and 3- to 5-mm nodules is highly suggestive of the diagnosis.

The combination of air cysts and 3- to 5-mm nodules is highly suggestive of the diagnosis.

SUGGESTED READING

Attili AK, Kazerooni EA, Gross BH, et al. Smoking related interstitial lung disease: radiologic-clinical-pathologic correlation. radiographics 2008;28:1383–1398.

Leatherwood DL, Heitkamp DE, Emerson RE. Best cases from the AFIP: Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Radiographics 2007;27:265-268.

LAURA E. HEYNEMAN

HISTORY

A 65-year-old man with progressive dyspnea and dry cough.

FIGURE 1-9A Posteroanterior chest radiograph. There are bilateral irregular linear opacities with low lung volumes. There is no evidence of adenopathy and there are no pleural abnormalities.

FIGURE 1-9A Posteroanterior chest radiograph. There are bilateral irregular linear opacities with low lung volumes. There is no evidence of adenopathy and there are no pleural abnormalities.

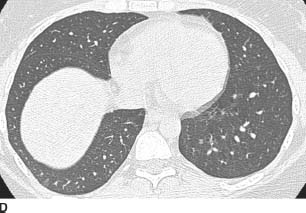

FIGURE 1-9B and 1-9C HRCT images of the chest (lung window) shows irregular linear opacities, traction bronchiectasis, and honeycomb cyst formation. The findings are subpleural in distribution and most severe in the lung bases.

FIGURE 1-9B and 1-9C HRCT images of the chest (lung window) shows irregular linear opacities, traction bronchiectasis, and honeycomb cyst formation. The findings are subpleural in distribution and most severe in the lung bases.

Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP): This is the most likely diagnosis because of the pattern of subpleural irregular linear opacities, traction bronchiectasis, and honeycombing that is most marked in the lung bases.

Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP): This is the most likely diagnosis because of the pattern of subpleural irregular linear opacities, traction bronchiectasis, and honeycombing that is most marked in the lung bases.

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP): NSIP is the second most common type of fibrosis, and is even more strongly associated with collagen vascular diseases than UIP. Honeycomb change is not a characteristic finding in NSIP. Therefore, while the irregular reticu-lar opacities and low lung volumes seen in this patient are indicative of fibrosis and would be seen in NSIP, the presence of honeycombing would make NSIP a much less likely diagnosis.

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP): NSIP is the second most common type of fibrosis, and is even more strongly associated with collagen vascular diseases than UIP. Honeycomb change is not a characteristic finding in NSIP. Therefore, while the irregular reticu-lar opacities and low lung volumes seen in this patient are indicative of fibrosis and would be seen in NSIP, the presence of honeycombing would make NSIP a much less likely diagnosis.

Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (CHP): CHP may result in a fibrosis that is very difficult to distinguish from UIP. Both entities may cause honeycomb cyst formation. However, CHP tends to cause fibrosis that is upper lobe predominant. Additionally, small centrilobu-lar nodules are often seen in CHP, and are not typically present in UIP.

Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (CHP): CHP may result in a fibrosis that is very difficult to distinguish from UIP. Both entities may cause honeycomb cyst formation. However, CHP tends to cause fibrosis that is upper lobe predominant. Additionally, small centrilobu-lar nodules are often seen in CHP, and are not typically present in UIP.

Sarcoidosis: The fibrosis associated with pulmonary sarcoid tends to have a perihilar and upper lobe predominance, particularly affecting the posterior aspects of the upper lobes. Therefore, the lower lobe predominance of the abnormalities seen in this case would not be characteristic of sarcoidosis. Additional radiologic clues that would suggest sarcoid would include lymph-adenopathy, upper lobe perilymphatic nodules, and progressive massive fibrosis.

Sarcoidosis: The fibrosis associated with pulmonary sarcoid tends to have a perihilar and upper lobe predominance, particularly affecting the posterior aspects of the upper lobes. Therefore, the lower lobe predominance of the abnormalities seen in this case would not be characteristic of sarcoidosis. Additional radiologic clues that would suggest sarcoid would include lymph-adenopathy, upper lobe perilymphatic nodules, and progressive massive fibrosis.

DIAGNOSIS

Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP)

KEY FACTS

Clinical

UIP typically manifests in middle-aged to elderly adults with progressive dyspnea and dry cough.

UIP typically manifests in middle-aged to elderly adults with progressive dyspnea and dry cough.

UIP is a pathologic diagnosis and is caused by multiple entities such as asbestos exposure (“asbestosis”) and collagen vascular disease. However, in the majority of patients, there is no known cause; when there is no known etiology of the UIP, the patient is said to have idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

UIP is a pathologic diagnosis and is caused by multiple entities such as asbestos exposure (“asbestosis”) and collagen vascular disease. However, in the majority of patients, there is no known cause; when there is no known etiology of the UIP, the patient is said to have idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

UIP is more common in smokers and former smokers.

UIP is more common in smokers and former smokers.

UIP is a progressive, fatal illness with a median survival of 4 years.

UIP is a progressive, fatal illness with a median survival of 4 years.

Corticosteroid and cytotoxic therapy is of limited benefit. Lung transplantation is a viable option in appropriate candidates.

Corticosteroid and cytotoxic therapy is of limited benefit. Lung transplantation is a viable option in appropriate candidates.

Radiologic

Typical chest radiographic manifestations of UIP include low lung volumes and irregular linear opacities, which are more severe in the lung bases. There may be cystic lucencies due to honeycombing; this finding is often more conspicuous on the lateral view.

Typical chest radiographic manifestations of UIP include low lung volumes and irregular linear opacities, which are more severe in the lung bases. There may be cystic lucencies due to honeycombing; this finding is often more conspicuous on the lateral view.

Pleural effusions are rare.

Pleural effusions are rare.

On HRCT, UIP manifests with irregular linear opacities (intralobular lines and irregular septal thickening), traction bronchiectasis, bronchiolectasis, and honeycomb cyst formation. When this pattern of findings is seen in a subpleural, basilar distribution, the HRCT is considered diagnostic of UIP.

On HRCT, UIP manifests with irregular linear opacities (intralobular lines and irregular septal thickening), traction bronchiectasis, bronchiolectasis, and honeycomb cyst formation. When this pattern of findings is seen in a subpleural, basilar distribution, the HRCT is considered diagnostic of UIP.

Ground glass opacities may be seen on HRCT, but are less extensive than the reticular, linear opacities.

Ground glass opacities may be seen on HRCT, but are less extensive than the reticular, linear opacities.

Lymphadenopathy is seen in 70% of patients, although the lymph node enlargement is usually mild (<1.5 cm in short axis).

Lymphadenopathy is seen in 70% of patients, although the lymph node enlargement is usually mild (<1.5 cm in short axis).

A search for the etiology of the UIP should be made on both radiographs and CT. For example, esophageal dilation or resorption of the distal clavicles raises the possibility of an underlying collagen vascular disorder. The presence of pleural plaques in the setting of UIP suggests a diagnosis of asbestosis.

A search for the etiology of the UIP should be made on both radiographs and CT. For example, esophageal dilation or resorption of the distal clavicles raises the possibility of an underlying collagen vascular disorder. The presence of pleural plaques in the setting of UIP suggests a diagnosis of asbestosis.

Complications of UIP that may be seen on the radiograph include pneumomediastinum or pneumothorax; these are caused by rupture of a distal alveolus in the context of stiff, noncompliant lung. Other complications that may be radiographically apparent include mycetoma formation within honeycomb cysts and lung cancer.

Complications of UIP that may be seen on the radiograph include pneumomediastinum or pneumothorax; these are caused by rupture of a distal alveolus in the context of stiff, noncompliant lung. Other complications that may be radiographically apparent include mycetoma formation within honeycomb cysts and lung cancer.

SUGGESTED READING

Mueller-Mang C, Grosse C, Schmid K, et al. What every radiologist should know about idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Radiographics 2007;27:595–615.

Silva CI, Muller NL. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. J Thorac Imaging 2009;24:260–273.

LAURA E. HEYNEMAN

HISTORY

A 58-year-old previously healthy woman with progressive dyspnea, cough, and low-grade fever over the past 6 weeks.

FIGURE 1-10A Posteroanterior chest radiograph reveals bilateral peripheral homogeneous opacities within the lower lobes (right greater than left) and right upper lobe.

FIGURE 1-10A Posteroanterior chest radiograph reveals bilateral peripheral homogeneous opacities within the lower lobes (right greater than left) and right upper lobe.

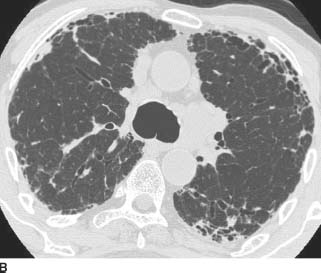

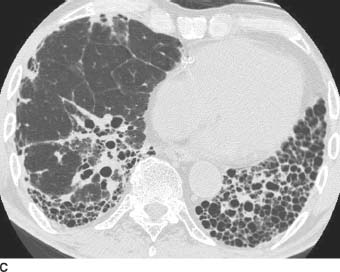

FIGURE 1-10B Chest CT (lung window) shows bilateral, right greater than left, subpleural lower lobe consolidation with air bronchograms. There is no pleural effusion. Incidental note is made of a calcified paraesophageal lymph node.

FIGURE 1-10B Chest CT (lung window) shows bilateral, right greater than left, subpleural lower lobe consolidation with air bronchograms. There is no pleural effusion. Incidental note is made of a calcified paraesophageal lymph node.

FIGURE 1-10C Chest CT (lung window) shows a focus of nodular ground glass opacity within the right lower lobe; this ground glass opacity is surrounded by a rim of consolidation (the “reversed halo” sign). Additional small foci of ground glass opacity and consolidation are present bilaterally. The anterior left upper lobe foci are subpleural in distribution.

FIGURE 1-10C Chest CT (lung window) shows a focus of nodular ground glass opacity within the right lower lobe; this ground glass opacity is surrounded by a rim of consolidation (the “reversed halo” sign). Additional small foci of ground glass opacity and consolidation are present bilaterally. The anterior left upper lobe foci are subpleural in distribution.

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP): This is the most likely diagnosis, given the patient’s symptoms as well as the CT findings of peripheral consolidation and the “reversed halo” sign.

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP): This is the most likely diagnosis, given the patient’s symptoms as well as the CT findings of peripheral consolidation and the “reversed halo” sign.

Atypical pneumonia: Atypical infections such as TB and invasive fungal infections may cause multifocal consolidation and have been described as resulting in the “reversed halo” sign on CT. However, in this case, the clinical history would make these infections much less likely.

Atypical pneumonia: Atypical infections such as TB and invasive fungal infections may cause multifocal consolidation and have been described as resulting in the “reversed halo” sign on CT. However, in this case, the clinical history would make these infections much less likely.

Eosinophilic pneumonia: Although chronic eosino-philic pneumonia should be considered in the differential for subpleural consolidation, it usually manifests with peripheral, upper lobe consolidation that parallels the chest wall. Furthermore, to date, eosinophilic pneumonia has not been described as a cause of the “reversed halo” sign.

Eosinophilic pneumonia: Although chronic eosino-philic pneumonia should be considered in the differential for subpleural consolidation, it usually manifests with peripheral, upper lobe consolidation that parallels the chest wall. Furthermore, to date, eosinophilic pneumonia has not been described as a cause of the “reversed halo” sign.

Wegener’s granulomatosis: A vasculitis can cause constitutional symptoms, pulmonary nodules, and the “reversed halo” sign on CT. Pulmonary hemorrhage from Wegener’s granulomatosis may result in multifo-cal consolidation with air bronchograms. However, the absence of hemoptysis or epistaxis in this case would make a diagnosis of Wegener’s granulomatosis unlikely.

Wegener’s granulomatosis: A vasculitis can cause constitutional symptoms, pulmonary nodules, and the “reversed halo” sign on CT. Pulmonary hemorrhage from Wegener’s granulomatosis may result in multifo-cal consolidation with air bronchograms. However, the absence of hemoptysis or epistaxis in this case would make a diagnosis of Wegener’s granulomatosis unlikely.

Alveolar sarcoidosis: While this is a differential consideration for chronic air space opacities and has been described as a cause of the “reversed halo” sign, the age of the patient, the clinical signs and symptoms, and the lack of adenopathy argue against sarcoidosis.

Alveolar sarcoidosis: While this is a differential consideration for chronic air space opacities and has been described as a cause of the “reversed halo” sign, the age of the patient, the clinical signs and symptoms, and the lack of adenopathy argue against sarcoidosis.

Multifocal bronchioalveolar carcinoma (BAC): Bron-chioloalveolar cell carcinoma may result in chronic, multifocal ground glass, nodules, and consolidation, and the regions of consolidation may demonstrate air bron-chograms. However, BAC has not yet been described as resulting in the “reversed halo” sign. Additionally, the clinical history would favor COP over BAC.

Multifocal bronchioalveolar carcinoma (BAC): Bron-chioloalveolar cell carcinoma may result in chronic, multifocal ground glass, nodules, and consolidation, and the regions of consolidation may demonstrate air bron-chograms. However, BAC has not yet been described as resulting in the “reversed halo” sign. Additionally, the clinical history would favor COP over BAC.

Pulmonary lymphoma: Again, although the presence of consolidation and nodules may be consistent with lymphoma, the clinical history and the presence of the “reversed halo” sign makes COP more likely.

Pulmonary lymphoma: Again, although the presence of consolidation and nodules may be consistent with lymphoma, the clinical history and the presence of the “reversed halo” sign makes COP more likely.

DIAGNOSIS

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP)

KEY FACTS

Clinical

Organizing pneumonia is caused by a loose plug of connective tissue within distal small airways with resultant chronic inflammation of the adjacent lung parenchyma. Histologically, this is known as bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP). Fifty percent of cases of BOOP are idiopathic; the remainder are associated with collagen vascular disease, drug toxicity, toxic fume exposure, infection, radiation therapy, or recurrent aspiration.