CHOANAL ATRESIA AND NASAL PYRIFORM APERTURE STENOSIS AND INFANTILE UPPER AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

KEY POINTS

- Computed tomography is critical to medical decision making in infantile upper airway obstruction.

- Magnetic resonance imaging is useful for problem solving and searching for associated anomalies.

Congenital nasal airway obstruction due to a fixed anatomic obstruction in infants is mainly due to choanal atresia or stenosis. Congenital nasal pyriform aperture stenosis (CNPAS) is a very much less common cause of upper respiratory obstruction in infants and young children and is far more likely to be misdiagnosed due to a lack of familiarity with the normal appearance and dimensions of the nasal cavity in infants. Congenital anterior nasal cavity obstruction has been noted as a cause of respiratory difficulties by several authors,1–3 and CNPAS was probably first described in the radiology literature4 in 1988 and first described clinically in 1989.5 In choanal atresia, a bone and/or membranous plate obstructs the posterior nasal cavity, while in CNPAS there is a narrowed but patent anterior nasal cavity.

Clinically, these two entities, CNPAS and choanal atresia, may be mimics. Infants affected present with respiratory distress at birth or very early in life, with the first event possibly triggered by an upper respiratory infection that further compromises an already narrowed nasal passage. A nasogastric tube may be difficult to pass, and symptoms may be more pronounced during feeding and relieved by crying in both, a pattern termed cyclic cyanosis.

Otherwise, nasal obstruction in infants that comes to imaging will be due to developmental masses such as an encephalocele (Chapter 79) or teratoma, nasolacrimal duct obstruction (Chapter 67), venolymphatic or other vascular malformations (Chapter 82), or even more rarely a tumor such as a chordoma or rhabdomyosarcoma.

GENERAL EMBRYOLOGY

The general development of the face and nasal cavity is reviewed in Chapter 79.

TABLE 81.1

From Belden CJ, Mancuso AA, Schmalfuss IM. CT features of congenital nasal piriform aperture stenosis: Initial experience. Radiology. 1999;213(2): 495–501, with permission.

In choanal atresia, the fusion of the palatal processes is likely the directing influence. These fused processes separate the nasal cavities and the oral cavity. The thinning of the palatal processes normally results in the two-layer membrane of nasal and oral linings that ruptures to form the posterior choanae. Failure of this bucconasal membrane rupture is the most likely cause of choanal atresia.

CNPAS may be due to a deficiency of the primary palate and/or a bone overgrowth in the nasal process of the maxilla.4,5

ANATOMY: NORMATIVE SIZE OF THE NASAL APERTURE, NASAL CAVITY, AND POSTERIOR CHOANAE AS SEEN ON COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

The normal anatomy of the nasal cavity is discussed in detail in Chapter 78.

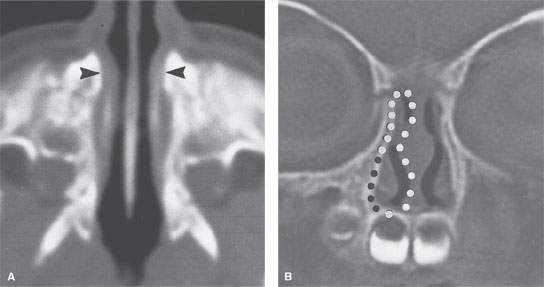

The average widths of the normal piriform aperture at ages 0 to 3, 4 to 6, and 10 to 12 months are 13.4, 14.9, and 15.6 mm, respectively6 (Table 81.1 and Fig. 81.1).

The average width of the posterior choana in the 0- to 3-month age group is 14.9 mm, in the 4- to 6-month age group is 14.7 mm, and in the 10- to 12-month age group is 17.0 mm. (Table 81.2 and Fig. 81.2)

CHOANAL ATRESIA

Introduction and Clinical Presentation

In bilateral atresia, there will be signs and symptoms in the neonate as described in the introduction to this chapter. Crying may alleviate the symptoms. Unilateral disease may present much later in life as chronic, unilateral nasal congestion/ obstruction (Fig. 81.3). Respiratory distress is not typically seen in unilateral choanal atresia.

Choanal atresia is most likely due to failure of the bucconasal membrane to rupture. There is often medial outgrowth of vertical and horizontal processes of the palatine bone, suggesting that mesodermal flow directed by neural crest cell migration is deranged possibly as a primary or secondary factor. Whatever the cause, there are fairly typical expressions with a wide variety of appearances in any given individual of this abnormal anatomy.

Choanal atresia has its major developmental associations with CHARGE syndrome; thus, it is necessary to fully assess the systemic implications of this association whenever bilateral choanal atresia is encountered.

Imaging Evaluation and Findings

Computed tomography (CT) is generally used first in evaluating infants with upper airway obstruction since bony abnormality is of primary interest. Magnetic resonance (MR) is reserved for problem solving such as when the obstruction turns out to be due to an encephalocele or mass and to search for associated anomalies.

The CT may show a high-arched palate and will show various degrees of bony and membranous stenosis (Figs. 81.3–81.6). The nasal cavity should be cleared of secretions and treated with a vasoconstrictor if one wishes to avoid overestimating the degree of soft tissue stenosis present (Fig. 81.3).

There is generally a markedly narrowed distance between an often thickened and deformed vomer and the posterior edge of the hard palate (Figs. 81.3–81.6). The vertical and horizontal plates of the palatine bone may be thick and deformed (Figs. 81.4 and 81.5). An accurate determination of the actual thickness of the bony atretic plate, as well as the degree of soft tissue stenosis present, is critical for surgical planning.

FIGURE 81.1. Computed tomography (CT) images obtained through a normal nasal cavity. A: Axial image through the inferior meatus. The width of the pyriform aperture is measured between the arrowheads. B: Coronal CT image through the nasal pyriform aperture. The area is measured by tracing each side individually along the bone margin of the aperture, as illustrated with the black and white dots. (From Belden CJ, Mancuso AA, Schmalfuss IM. CT features of congenital nasal piriform aperture stenosis: Initial experience. Radiology. 1999;213(2): 495–501, with permission.)

TABLE 81.2

FIGURE 81.2. Coronal image through the posterior choana. The width of the choana is measured between the arrowheads. The area of the choana on each side is traced along the bone margins of the choana, as illustrated with the dots. (From Belden CJ, Mancuso AA, Schmalfuss IM. CT features of congenital nasal piriform aperture stenosis: Initial experience. Radiology. 1999;213(2):495–501, with permission.)

FIGURE 81.3. A–C: An infant born with some respiratory distress, and right nasal obstruction was noted on physical examination. In (A), the coronal reformation shows very marked reduction in the area of the posterior choana on the right (white arrow) caused by both abnormal bone and soft tissue (black arrow). In (B), a section slightly more anterior than (A) shows the lower aspect of the posterior choana to be somewhat reduced in size (white arrow) but the upper portion to be more narrowed by the dysmorphic vomer and vertical plate of the palatine bone (black arrow). In (C), axial views show a dysmorphic vomer (arrowhead) and the right nasal cavity partially filled with secretions. The nature of the obstruction on the right might have been better determined by suctioning the airway and treating with vasoconstrictors before the computed tomography study. D–F: An adult patient with narrowing of the right nasal cavity and posterior choana. In (D), the coronal view at the posterior choana shows a predominately soft tissue atresia. In (E), the axial view shows a soft tissue thickening at the posterior choana (arrow) and the overall narrowing of its bony limits. In (F), the sagittal reformation shows a combination of bony and soft tissue changes narrowing the posterior choana (arrow).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree