Type

Common location

Mode of spread

Typical imaging findings

Prognosis

Mass forming

Intrahepatic

Invading and penetrating the bile duct wall, spreading between hepatocytes plates

Infiltrative hepatic mass with capsular retraction or peripheral ductal dilatation

Unfavorable

Irregular rim-like enhancement around periphery of tumor on arterial phase and progressive enhancement on delayed phase images

Periductal infiltrating

Hilar or extrahepatic

Spread along the bile duct wall via the nerve and perineural tissue

Mural and periductal soft-tissue thickening or focal irregularities of the bile duct

Unfavorable

Intraductal growing

Intrahepatic or extrahepatic

Frequently present with long range of mucosal spread

Focal or diffuse ductal dilatation with multifocal papillary or sessile masses

Favorable after surgical resection

14.3.1 Mass-Forming CC

Mass-forming CC is the most common type of intrahepatic CC. It arises from the mucosa of a branch of the bile ducts in the peripheral area of the liver, invading and penetrating the bile duct wall, and spreads between hepatocytes plates. It has a propensity to invade small adjacent portal branches in the form of venous tumoral thrombi. Macroscopically, mass-forming CC is characterized by a white, firm, homogeneous sclerotic mass with an irregular lobulated margin, typically in the absence of hemorrhage or necrosis. The viable tumor cells are usually located at the periphery of the tumor. Characteristically this tumor has a large central core of fibrotic tissue, due to the desmoplastic reaction induced by the neoplastic cells. Microscopically, CC represents an adenocarcinoma with its tubular or acinar-glandular structures.

14.3.2 Periductal-Infiltrating CC

Periductal-infiltrating CC is the most common type of hilar CC. Arising from the mucosa of the intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile ducts, the tumor invades the wall and penetrates to the serosa. The tumor appears as a diffuse, firm, grays-white, annular thickening of the bile duct causing almost complete obstruction of the lumen. In contrast to mass-forming CC, infiltrating CC tends to spread along the bile duct wall via the nerve and perineural tissue of Glisson’s capsule toward the porta hepatis. Macroscopically, this neoplasm appears as elongated, spiculated, or branch-like annular thickening of the bile duct walls. Irregular narrowing of the involved bile ducts eventually results in the obstruction of the lumen.

14.3.3 Intraductal-Growing CC

Intraductal-growing CC is a low-grade papillary adenocarcinoma, composed of innumerable frond-like infoldings of columnar epithelial cells and fibrovascular cores. The tumor cells are confined within the mucosal layer, spread superficially without invading the submucosal layer. The tumor cells are friable and may slough spontaneously from the walls of the bile ducts. The tumors are usually small, sessile, or polypoid, but sometimes a large mass may occlude an aneurysmally dilated bile duct. The biliary tract may be dilated diffusely in a lobar or segmental fashion. When an intraductal CC produces a large amount of mucin, it is called intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) of the bile ducts.

14.4 CC Evaluation on Imaging

14.4.1 Role of Imaging

Surgical resection is the best available and potentially curative therapy for CC. Technical advances in diagnostic imaging allow better selection of surgical candidates. Ultrasonography accurately recognizes biliary tract dilatation and is helpful in depicting intraductal tumors. Cross-sectional imaging such as CT and MRI are the primary tools used in the assessment of longitudinal and lateral spread of CC and determining respectability. MDCT is a widely used noninvasive examination for the staging of CC. MDCT is an excellent imaging technique for evaluating the soft-tissue extent of CC and its relation between the tumor and the hepatic vasculature. Recently, fusion imaging techniques have been introduced. It may display tumor itself as well as the surrounding vessels and demonstrate complex anatomic relationship of bile duct cancer. These techniques seem to have a potential to improve treatment planning with MDCT. MR imaging in combination with MRCP can be used as a sole imaging modality for evaluation of bile duct cancer. The roles of MRI combined with MRCP are (1) to differentiate benign from malignant causes of biliary stricture, (2) to determine resectability in patients with bile duct cancer, (3) to preoperatively stage, (4) and to differentiate between the different appearances of growth patterns. Direct cholangiography including ERCP and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) is still the standard of reference for biliary extent of the tumors. FDG-PET is valuable for detecting unsuspected distant metastases particularly in patients with peripheral CC because of the likelihood of distant metastases at the time of diagnosis and the high uptake in the peripheral type. Also, it has been reported that FDG-PET evaluates the lymph node metastases more accurately compared with CT.

14.4.2 Imaging Findings

14.4.2.1 Mass-Forming CC

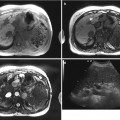

Mass-forming CC manifests as a solitary mass in the liver parenchyma with a nodular pattern. Lesions smaller than 3 cm tend to be homogeneously hypoechoic or isoechoic, whereas tumors larger than 3 cm are predominantly hyperechoic on US. A peripheral hypoechoic area or halo sign can be observed. However, it shows diverse echo patterns and may be hypo-, iso-, or hyperechoic and homogeneous or heterogeneous. Peripheral ductal dilatation is occasionally associated.

Unenhanced CT scan may show a predominantly hypoattenuating mass. Calcification may be seen in the central portion of the lesions, especially in mucin-secreting tumors. Typical enhancement patterns on CT are marked hypoattenuation with thin, incomplete peripheral enhancement during arterial and portal venous phases and centripetal progression of enhancement over time. The morphology of peripheral CC on imaging as well as its histology is similar to that of metastatic adenocarcinoma, but CC is more likely to be solitary, large, with occasional association with peripheral ductal dilatation. The peripheral portion has viable cancer cells that show incomplete rim enhancement on arterial phase and peripheral washout. The central portion contains more fibrous stroma and shows mild centripetal progression and delayed or prolonged enhancement on dynamic CT or MR. Other common findings of CC include frequent capsular retraction because of desmoplastic reaction, marked hypoattenuation from mucin component, satellite nodules, extracapsular extension, lymphadenopathy, and vascular encasement within the mass. It has been reported that small (<3 cm in diameter) mass-forming CCs in the cirrhotic liver show atypical enhancement patterns more frequently than large (<3 cm) mass-forming CCs and may thus mimic hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs). Two thirds of mass-forming CCs show the typical enhancement pattern of arterial hypoattenuation and hypo-, iso-, or hyperattenuation in the portal venous and/or equilibrium phase. One third of mass-forming CC show atypical enhancement pattern such as arterial enhancement with or without washout.

On MRI, the typical appearance of the tumor is a nonencapsulated mass that is hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences. The mass-forming CC is better seen on T2-weighted images and has no capsule. Central hypointensity corresponding to fibrosis and peripheral hyperintense rim may be seen on T2-weighted images. Since internal desmoplastic changes are intermingled with various degrees of fibrosis, coagulative necrosis, and mucin, the signal intensity of the tumor center on T2-weighted images is variable. Recently, enhancement patterns on gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI were reported. The most prevalent enhancement patterns of intrahepatic mass-forming CCs on gadoxetic acid-enhanced MR images were a thin peripheral rim with internal heterogeneous enhancement on dynamic phase images and heterogeneous hypointensity with intermingled hyperintensity due to retained contrast material in fibrotic stroma on hepatobiliary phase images. Hepatobiliary phase may aid in the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma because of increased lesion conspicuity and better delineation of daughter nodules and intrahepatic metastasis.

The contrast enhancement pattern of mass-forming CC differs from that of HCC which typically shows strong enhancement on arterial phase and washout on portal or delayed phase images. Sclerosing HCC should be differentiated from mass-forming CC because they have abundant fibrous stroma. There are other helpful findings for the differential diagnosis between mass-forming CC and HCC. Most mass-forming CC occur in non-cirrhotic livers, may show intratumoral calcifications but no intralesional fat, does not have a pseudocapsule, and frequently causes bile duct dilatation. Hypovascular metastases, especially from adenocarcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract, may have a similar appearance to that of mass-forming CC. Suggestive features for the diagnosis of mass-forming CC are a relatively large single tumor at discovery, few satellites nodules rather than multiple scattered nodules, and other additional findings such as adjacent bile duct dilatation, and retraction of liver capsule.

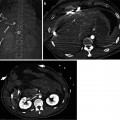

14.4.2.2 Periductal-Infiltrating CC

Periductal-infiltrating CC is characterized by growth along the bile duct appearing as elongated, spiculated, or branch-like lesions. Dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts is the most frequent abnormality seen in patients with periductal-infiltrating CC on ultrasonography. Periductal-infiltrating CC is the most common type but is difficult to evaluate with sonography. Contrast-enhanced sonography can be useful for detecting and staging of hilar CC in the postvascular phase.

Most periductal-infiltrating CC appears as mural and periductal soft-tissue thickening or focal irregularities of the bile duct with subsequent obstruction and pre-stenotic bile duct dilatation. In periductal-infiltrating CC, irregular and ill-defined thickening of the ductal wall can be seen in contrast-enhanced CT or MRI, which is often hyperattenuating or hyperintense relative to the liver parenchyma in the arterial and portal venous phase. Lobar atrophy and blood vessel crowding may be useful secondary signs. With MDCT, bile duct cancer can be correctly identified in nearly 100 % of patients. The accuracy of MDCT in prediction of respectability has improved to 75–90 %. Multiphasic CT is helpful for assessment of the relation between a tumor and the hepatic hilar structures. Arterial phase images are useful for evaluating anatomic variations in the hepatic arteries and arterial invasion by the tumor. Portal venous phase images emphasize the relation between the tumor and the portal vein and adjacent hepatic parenchyma. Portal venous involvement in CC is encasement and narrowing of the vessel rather than luminal invasion. Postprocessing techniques such as maximum intensity projection, multiplanar reformation, and volume rendering allow depiction of vascular structures and the biliary tree with or without administration of biliary contrast media. Adding routine coronal and sagittal reformation to standard axial images may not improve overall diagnostic accuracy in the detection of bile duct cancer with respect to tumor extent, vascular involvement, or resectability. However, more vigorous use of postprocessing techniques such as oblique and curved reformation with volume rendering may increase the diagnostic confidence and has the potential to improve diagnostic accuracy in the assessment of tumor extent along the bile duct and vessel invasion.

14.4.2.3 Intraductal CC

The most characteristic pattern of intraductal cholangiocarcinoma is diffuse ductal dilatation with multifocal papillary or sessile masses. At ultrasound, intraductal polypoid lesion is echogenic relative to the surround liver parenchyma. The bile ducts proximal to the tumor are dilated and the degree of dilatation depends on the degree of obstruction. On ultrasound or CT, an intraductal mass appears as a papillary tumor or castlike lesion within the dilated bile duct. As this lesion is usually confined to the bile duct wall, the wall appears intact on ultrasound and CT. After contrast medium injection, the intraductal tumors show enhancement. In some cases, only marked intrahepatic bile duct dilatation with no obstructive mass or stricture can be detected on CT or MRI. Some papillary tumors of the bile ducts produce a large amount of mucin. Even though ultrasound, CT, and MRI might show severe dilatation of the intra- and extrahepatic ducts, visible mass may not appear on the images or gross examination. Both proximal and distal bile ducts to the tumor are dilated because mucin may obstruct the ampulla of Vater. Intraductal tumors may manifest itself as localized ductal dilatation with intraductal mass. When an intraductal papillary mass do not secrete mucin, the distal ductal dilatation is not prominent. This type of intraductal tumor may be confused with an intraductal masslike stone. The absence of contrast enhancement is useful in making the diagnosis of an intraductal masslike stone, whereas an enhancing polypoid lesion with asymmetric adjacent bile duct wall thickening is suggestive of an intraductal tumor. The most difficult type to diagnose is intraductal castlike lesions within a mildly dilated duct. It appears as an area of mild ductal dilatation filled with intraductal soft-tissue material which may show mild enhancement on CT or MR imaging. Rarely, intraductal tumor may appear as a focal stricture-like lesion with mild proximal ductal dilatation. The stricture may be a secondary finding of the underlying inflammation and fibrotic stricture or may itself represent a small tumor.

14.5 Staging and Evaluation of Resectability

14.5.1 Staging

14.5.1.1 Intrahepatic CC

CC staging is clinically important to identify the candidates for surgical resection. The most important prognostic factors in intrahepatic CC are tumor size, lymph node metastasis, multiple tumors or intrahepatic metastasis, and vascular invasion. Serosal invasion is not considered a prognostic factor. Vascular involvement is observed in 50 % of cases. The presence of segmental or lobar atrophy is strongly associated with ipsilateral portal vein encasement. The overall accuracy of detecting metastatic lymph node is 70–80 %, and the most common error on preoperative imaging is underestimation of nodal involvement.

14.5.1.2 Extrahepatic CC

There are currently two staging systems used for extrahepatic CC. The first is that of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), which incorporates extent of tumor invasion into the wall of the bile duct, as well as lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis. This system is helpful in identifying prognostic subsets, but is applicable only to the minority of patients who undergo surgical resection. The modified Bismuth-Corlette classification system provides an anatomical description of the tumor and is useful in determinating resection or palliative treatment and the type of surgery. However, it is not indicative of survival. During the staging of extrahepatic CC, the proximal and distal margins of the tumor should be clearly identified. Longitudinal spread pattern of the tumor is related to gross morphology. The infiltrating tumors tend to show subepithelial extension, while papillary tumors frequently present with long range of mucosal spread. Therefore, determination of longitudinal spread must be made cautiously when a papillary tumor is found. It is also important to exclude vascular encasement of the contralateral liver lobe in hilar or extrahepatic CC before committing to partial hepatectomy and to verify vascular patency of the portal vein and hepatic artery. This usually can be accomplished by CT or MRI. Finally, regional metastases should be ruled out. However, current imaging modalities have limitation in determining metastatic lymph node involvement.

14.5.2 Resectability

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree