CHRONIC SINUSITIS AND NASAL POLYPOSIS

KEY POINTS

- Imaging should be used only in an appropriately triaged group of patients who have a clinical diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis.

- Imaging can identify underlying causative or alternative conditions that may significantly affect medical and surgical decision making.

- Imaging is critical in identifying the extent of disease and complications such as mucoceles and excluding orbital and intracranial complications of chronic sinusitis.

INTRODUCTION

Etiology

Rhinosinusitis

Sinusitis is an inflammation of the paranasal sinus mucoperiosteal lining. Rhinosinusitis is currently the preferred term for this condition because the nasal mucosa is almost always simultaneously involved when sinusitis occurs.1–4 An otolaryngology Rhinosinusitis Task Force has defined acute sinusitis as lasting up to 4 weeks, subacute sinusitis lasting >4 weeks but >12 weeks, and chronic sinusitis when symptoms last <12 weeks. Recurrent acute sinusitis is defined as more than four episodes per year with complete resolution between infections. Acute and subacute infectious rhinosinusitis is discussed in Chapter 84. Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) and the often related sinonasal polyposis are the subjects of this chapter. Other considerations in this chapter include the frequent association of this disease with mucocele formation and fungal colonization.

The pathophysiology of CRS is poorly defined, but many mediators of inflammatory disease have been identified as part of the disease process, establishing CRS as a predominantly inflammatory disease. Contributing factors are described in the following Pathophysiology section.

Chronic sinusitis, once felt to be infectious, is now felt to be due to an infectious etiology less commonly, although patients may have had their disease incited by infection or have become infected as a result of the chronic obstruction within the paranasal sinuses. Patients with a history of allergy, occupational or vasomotor rhinitis, nasal polyps, or anatomic obstruction such as septal deviation and concha bullosa will be predisposed to chronic infections. Rhinosinusitis is more common in immune-deficient patients; in those with ciliary motility problems such as Kartagener syndrome; and in those with mucous blanket problems, such as cystic fibrosis (CF) patients.

The term chronic rhinosinusitis is now preferred to describe this condition. The presence of CRS requires two or more of the following symptoms: mucopurulent drainage, nasal obstruction, or some combination of facial pain, pressure, and/or fullness; hyposomia; fever; cough; dental pain; and fatigue. There should also be endoscopic presence of inflammation and evidence of rhinosinusitis on imaging.

Common complications of chronic sinusitis are superimposed acute sinusitis and, in children, adenoiditis with secondary serous or purulent otitis media. Dacryocystitis and laryngitis may also occur as complications of chronic sinusitis in children. Other complications include osteomyelitis and mucocele formation.

Orbital complications (Chapter 84) include preseptal and postseptal cellulitis, subperiosteal abscess, orbital cellulitis, orbital abscess, and cavernous sinus thrombosis. Intracranial complications (Chapter 84) include meningitis, epidural abscess, subdural abscess, and brain abscess.

Nasal Polyposis

Nasal polyps arise from any portion of the nasal mucosa or paranasal sinuses as the end result of various sinonasal disease processes. The most common mucosal polyps are benign nasal cavity inflammatory lesions that arise from the mucosa of the nasal cavity or the paranasal sinuses often at the outflow tract of the sinuses. These have an inflammatory etiology, but the exact mechanisms are uncertain, as discussed in the following Pathophysiology section.

Multiple polyps often occur in patients with chronic sinusitis, allergic rhinitis possibly associated with allergic fungal sinusitis (AFS), and CF. Polyps are associated with both nonallergic disease and allergic disease. The term polyp may be used to describe any of a number of benign or malignant tumors or congenital lesions, but that is not the sense of the term in this chapter, although those conditions may enter the differential diagnosis.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

CRS affects about 10% to 15% of the population in the United States, making it more common than any other chronic condition. Its incidence is increasing for unknown reasons.

Rhinosinusitis is more common in children, likely secondary to the increased frequency of upper respiratory tract infections and asthma in the pediatric population.

Multiple inflammatory nasal polyps typically occur in those patients older than 20 years and are more common in those over 40 years. Nasal polyps are uncommon in children younger than 10 years except in those with CF.

The incidence worldwide is the same as that in the United States. Males are at least twice as likely to have inflammatory polyps as females.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms of CRS overlap with other disease processes, and there may be poor correlation between symptoms and endoscopic and imaging findings. Patients with uncomplicated rhinosinusitis can have rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, facial pressure and pain, diminished sense of smell, and perhaps fever. Less directly correlating symptoms include headache, ear pain or fullness, bad breath, dental pain, cough, fever, and fatigue.

Small polyps may not produce symptoms, only being seen during anterior rhinoscopy. Small polyps may also block the outflow tract of the sinuses, causing chronic or recurrent acute sinusitis symptoms.

Larger and/or more extensive polyps may cause nasal airway obstruction, postnasal drainage, headaches, snoring, and rhinorrhea. Disorders of olfaction suggest that polyps obstructing airflow into the olfactory cleft, rather than chronic sinusitis alone, are present. Epistaxis may occur, and it always creates a concern for a more serious nasal cavity lesions.

Extensive polyposis or a single large polyp obstructing the nasal cavities and/or nasopharynx can cause obstructive sleep symptoms and chronic mouth breathing. Mucoceles as a complication may alter craniofacial structure, especially in children. Proptosis, hypertelorism, and diplopia may be presenting complaints. Compression on the optic nerve is rare, and neurologic symptoms are extremely rare in the absence of a complicating intracranial infection.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Anatomy

The sinuses are divided into anterior and posterior groups that drain into the middle meatus anteriorly and into the sphenoethmoidal recess and superior meatus posteriorly. The anatomy is discussed in detail in Chapter 78, and the physiology of sinonasal mucus clearance related to this anatomy is considered in the following material and also in Chapter 83 on endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS).

The paranasal sinuses are lined with a pseudostratified columnar (respiratory) epithelium that is continuous with the nasal mucosa. The mucoperiosteal sinus and nasal lining produces mucous secretions that trap bacteria, and both the mucus and bacteria are transported along a mucous blanket through the sinus ostia to be swallowed or expectorated. This is a normal process in sinuses that are air filled and communicate with the nasal passages through patent ostia.

Pathology and Patterns of Disease

The pathophysiology of CRS is poorly defined, but many mediators of inflammatory disease have been identified as part of the disease process, establishing CRS as a predominantly inflammatory disease. Contributing factors in some patients include allergy; immunodeficiency; autoimmune disease; colonizing fungi that produce an ongoing eosinophilic inflammation; persistent infection including biofilms, osteitis, and bacterial supertoxins; upper airway intrinsic factors; chemical irritation; and metabolic abnormalities such as aspirin sensitivity.

All of these factors may disrupt the mucociliary transport system as described in Chapter 83 and 84 and encourage bacterial growth that contributes to increased mucosal inflammation.

The pathogenesis of nasal polyposis is unknown. Polyp development is most basically linked to chronic inflammation; thus, conditions leading to chronic inflammation in the nasal cavity can lead to nasal polyps. Such processes include bronchial asthma, CF, allergic rhinitis, AFS, CRS, primary ciliary dyskinesia, aspirin intolerance, alcohol intolerance, Churg-Strauss syndrome and Young syndrome and nonallergic rhinitis with eosinophilia syndrome (NARES), autonomic nervous system dysfunction, and genetic predisposition conditions may be contributing factors.

Polyps are lobulated, bulging, or protruded regions of the nasal or sinus mucosa that are displaced by underlying edematous stroma, often in combination with some degree of mucosal inflammation (Figs. 85.1 and 85.2). Inflammatory changes likely first occur in the lateral nasal wall or sinus mucosa as the result of a viral bacterial or bacterial “trigger” that begins the inflammatory response, with that process possibly being enhanced by turbulent airflow. The initiating incident may not be established.

Polyps most typically arise at contact areas within the middle meatus that create turbulent airflow, with the narrowing and related turbulence then exacerbated by mucosal inflammation (Fig. 85.1). It is thought that anatomic abnormalities that lead to narrowing of the middle meatus may increase the risk of polyp formation. Ulceration or prolapse of the submucosa occurs along with epithelial repair and new gland formation. A polyp can then form from the mucosa because of the heightened, ongoing inflammatory process of epithelial cells, vascular endothelial cells, and fibroblasts. This cycling process releases mediators that produce conditions favorable for water retention that increases the volume of the polyps (Fig. 85.2). Vasomotor imbalance may contribute by increasing vascular permeability and impairing vascular regulation within the polyp stroma, resulting in more marked edema. This factor is reflected in the cell-poor stroma of the polyps that is also poorly vascularized and lacks vasomotor control. Patients with CF have a cellular defect that supports the theory of water retention as a contributing factor to polyp formation (Fig. 85.2).

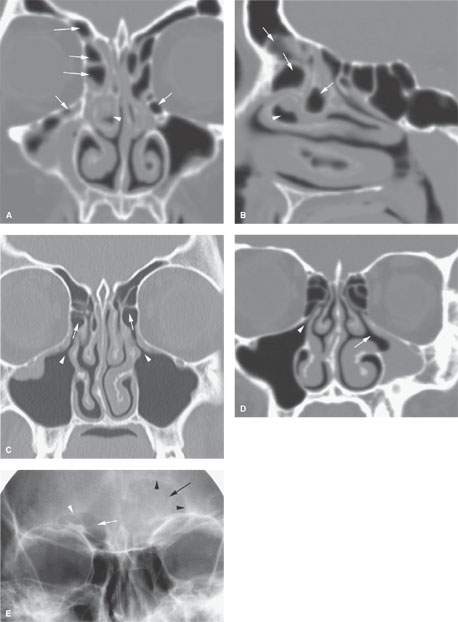

FIGURE 85.1. A, B: Coronal and sagittal reformatted images showing complex air cell development in the frontal recess and in the region of the infundibulum (arrows) that might contribute to altered airflow patterns and help to create the circumstances giving rise to chronic mucosal disease. On the right side, there is a diseased concha bullosa (arrowhead) that might further contribute to the situation and might explain why changes are worse on the right than on the left. C: Coronal computed tomography (CT) reformation showing that drainage from the maxillary sinus infundibulum (arrowheads) is into anterior ethmoid air cells (arrows) rather than directly into the middle meatus. Such a variant in the drainage pathways might be a contributing factor to chronic sinus disease. It also may be seen as a normal variant in the absence of such disease. D: On the right side of this coronal CT section, there is a normal maxillary sinus ostium (arrowhead) and configuration of the sinus to compare to the hypoplastic sinus on the left side with a abnormal arrangement of the medial sinus wall that likely is associated with disordered ciliary motion, leading to the chronic mucosal thickening seen (arrow). E: A patient with frontal region pain. This plain film shows a normally aerated frontal sinus on the right side (white arrow) and its normal somewhat undulating margin (white arrowhead). The left side of the frontal sinus is obviously less well aerated (arrow) and has lost its undulating margin, suggesting regressive remodeling due to mucocele (arrowheads). While this illustrates that plain films can successfully detect relatively advanced sinus disease, they are not as reliable as CT for excluding disease and certainly not for excluding erosive bony changes.

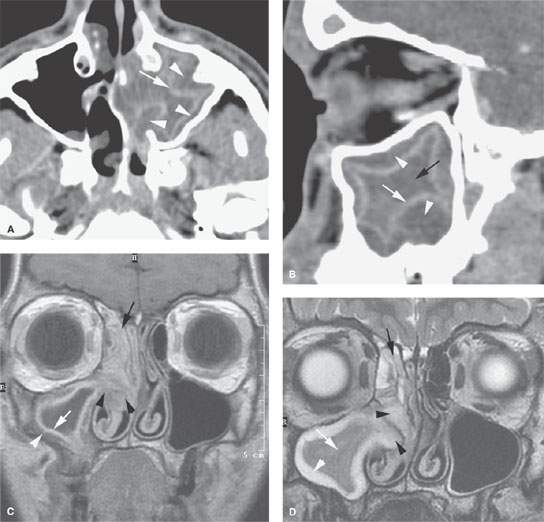

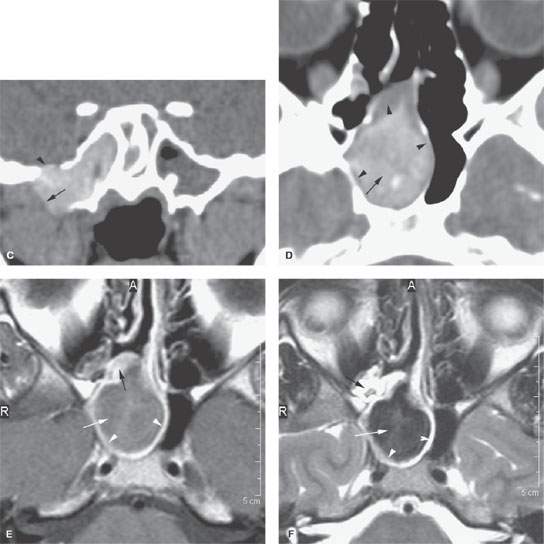

FIGURE 85.2. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) images in three patients meant to illustrate the pathophysiology of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS). A: Axial contrast-enhanced CT shows mucosal thickening (arrow). There is submucosal edema (arrowheads) that is contributing to the formation of the polypoid chronic mucosal disease that protrudes through the medial wall of the sinus into the nasal cavity. B: Sagittal reformation of the sinus seen in (B) points out the primary inflammation in the mucosa (white arrow), the secondary altered physiology of the submucosa, and accumulating fluid in that layer (white arrowheads) contributing to polyp formation. At this point in the evolution of the disease, there is still a considerable amount of trapped secretions within the sinus lumen (black arrow). C, D: MR images of an 18-year-old male with CRS initially believed to have a juvenile angiofibroma until imaging showed CRS-type polyps. In (C), the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image demonstrates right maxillary sinus mucosal thickening (white arrow) and submucosal edema (white arrowhead). These changes become a substrate for eventual polyp formation as seen in (A) and (B). Aggregate polypoid mucosal thickening has bulged from the sinus osteum into the nasal cavity (black arrowheads). Redundant inflamed mucosa (black arrow) is present in the ethmoids and contributes to the generalized right-sided polypoid mucosal thickening. At some point in the pathogenesis, this polypoid mucosal thickening creates sinus outlet obstruction as seen in this patient and eventually can cause the formation of a secondary mucocele. In (D), the T2-weighted coronal image illustrates the contribution of the watery submucosal changes to this pathophysiology. The submucosal edema in the sinus (white arrowhead) is actually composed of more free water than the luminal mucoid secretions (white arrow). The edematous stroma of the submucosal component of the polyps creates most of the polyp mass as seen protruding into the nasal cavity (black arrowheads). The combination of submucosal edema and intervening secretions or thickened mucosa is illustrated in the ethmoid sinuses (black arrow). E, F: Another patient demonstrating how dystrophic changes may affect the mucosa in chronic disease. In (E), the densities seen lining the mucosal surface and perhaps within luminal secretions can represent inspissated secretions, areas of fungal colonization, and/or dystrophic mucosal calcification. Dystrophic calcification is more likely to be peripheral (white arrow). Fungal-related changes and those due to inspissated secretions (white arrowheads) are more likely to be central. In (F), the axial image shows secretions that predominately line the mucosal surface (arrows)—findings more consistent with dystrophic changes within the mucosa than fungal colonization.

Complications

Mucoceles

Mucocele formation requires the obstruction of a draining ostium, complete opacification of a sinus, or an individual air cell within a sinus complex (Figs. 85.3–85.10). These conditions are most typically encountered in patients with CRS and especially in those with nasal polyposis. A prior history of either trauma or previous sinus or facial surgery is commonly encountered. In fact, patients with CRS and nasal polyposis may have very extensive mucoceles involving one or more sinus on either or both sides. The mucoceles can be sources of very significant consequences, including ocular motility disturbances, proptosis, hypertelorism, compressive optic neuropathy, and facial deformity. They may also become acutely infected, forming a mucopyocele that can lead to acute orbital and intracranial complications as discussed in Chapter 84.

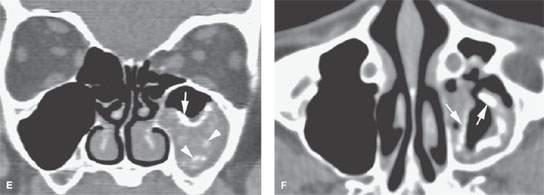

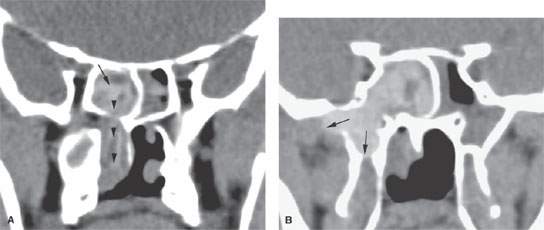

FIGURE 85.3. Images of two patients with sphenoid sinus mucocele. A–C: Patient 1. In (A), the coronal reformation shows chronic polyps formed within the sphenoid sinus (arrow) protruding through the sinus osteum and into the nasal cavity (arrowheads) as a sphenochoanal polyp. In (B), the same polypoid mass has caused regressive remodeling at the margins of the sphenoid sinus with the central skull base and the secondary mucocele composed of very inspissated secretions expanding into the masticator space and the base of the pterygoid plates (arrows). (continued) In (C), continued extension of this sphenoid sinus mucocele with impacted secretions includes a broad zone of dehiscence with the floor of the middle cranial fossa (arrowhead) and continued expansion into the infratemporal fossa is an indication of just how complex mucocele development can become. The density of the sinus lumen contents can be due just to drying of the secretions, but an association with fungal colonization and such drying is relatively high. D–F: Patient 2 with a sphenoid sinus mucocele. In (D), the mucocele bulges through the sinus osteum while it has caused obvious regressive remodeling of the sinus walls (arrowheads). The contents appear dense and likely desiccated and possibly fungal colonized as indicated by the central area of higher density (arrow). In (E), contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) magnetic resonance (MR) shows the mucocele to be composed of relatively thin enhancing mucosa (white arrowheads) with somewhat thicker enhancing mucosa blocking the ostium (black arrow). The luminal secretions appear of somewhat greater signal intensity than fluid (white arrow). In (F), T2-weighted (T2W) MR demonstrates the pathophysiology perhaps more graphically. The edematous mucosa within the sinus again remains relatively thin (arrows) with somewhat thicker (black arrow) polypoid mucosal thickening in the sphenoethmoidal recess and around the sphenoid ostium causing the primary obstruction. The T2W image provides a better idea of the desiccated nature of the luminal secretions (white arrow) than the T1W image.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree