CHAPTER 15 Clinical Techniques of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Function

The assessment of cardiac function provides valuable diagnostic and prognostic information when managing patients with cardiovascular disease. Advancements in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology have allowed for routine noninvasive assessment of left and right ventricular regional and global systolic and diastolic function.1 With the image acquisition methods described in Chapter 13, MRI is well suited to measure these crucial parameters, as evidenced by results produced from studies of phantoms, cadavers, animals, and human clinical trials.

Technical Requirements

Technical requirements for evaluating resting cardiac function require an MRI scanner with capabilities and protocols described in Chapter 13. Evaluating for dynamic measures of ventricular function, such as with dobutamine or exercise, necessitates further equipment (see later).

DETERMINING GLOBAL MEASURES OF CARDIAC FUNCTION

Indications and Clinical Utility

An accurate assessment of LV function is important for determining prognosis and appropriate therapy. MRI determinations of LV volumes using Simpson’s rule have been rigorously validated with cadaver studies. An early study showed excellent correlation (r = 0.997) between MRI-derived volume measurements of latex casts of excised human ventricles and the actual volume measurements from the casts themselves.2 Data derived from multiple autopsy series have shown a similarly high degree of correlation,3 as have animal studies using canine, porcine, rat, and mouse models.4,5,6

Several studies have demonstrated high reproducibility of MRI in the assessment of ejection fraction (EF) via Simpson’s rule methods. In one such investigation, intraobserver, interobserver, and interexamination variability were analyzed rigorously and measurements of LV volumes using MRI were more consistent compared with those obtained by other imaging modalities in prior studies.7 Another study found a 5% interobserver and interstudy variability in EF with cardiac MRI,8 superior to the 10% that has been reported for echocardiography.9 Notably, such consistency has been demonstrated in normal and morphologically abnormal (dilated and hypertrophied) left ventricles,10 for which other methods are vulnerable to inaccuracy.

Direct comparisons between MRI and other imaging techniques in the evaluation of EF have further bolstered the value of MRI in clinical practice. One of the first such studies compared MRI with ventricular angiography in calculating EF using the area-length method and found excellent correlation between the two (r = 0.88).11 More recently, MRI assessment of EF using Simpson’s rule has proved more reproducible (less interstudy, intraobserver, and interobserver variability) than two-dimensional echocardiography, currently the most widely available imaging modality to assess cardiac function.12,13 Also of note, direct comparisons among MRI, echocardiography, and radionuclide ventriculography revealed considerable differences in calculated EF, suggesting that MRI is the more accurate and preferred method to assess cardiac function, especially in dilated ventricles.14 Because of its consistent performance in clinical evaluations, MRI assessment of LV volumes using Simpson’s rule is now widely accepted as the most accurate and precise noninvasive estimation of EF.15

These benefits of MRI have research and clinical implications. Better reproducibility has resulted in the need for smaller sample sizes (sometimes by a factor of 80% to 90%) in studies using MRI measures of ventricular volumes than in those using other imaging modalities.3 Furthermore, MRI is now routinely used as the gold standard when evaluating other imaging techniques, such as three-dimensional echocardiography.16,17 MRI may be particularly important in evaluating patients for prophylactic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator placement,18 in which an EF of 35% is commonly used to guide the implantation of a device. MRI may also be useful in serial evaluations to detect changes in EF that are smaller than the limits of sensitivity of echocardiography. This can be especially relevant in identifying the subclinical cardiotoxic effects of chemotherapy.19

Contraindications

Because no stimulant or contrast agent is required to assess resting EF, the contraindications for this technique coincide with those pertaining to any MRI scan, such as the presence of certain metal implants or devices (see Chapter 19) or severe claustrophobia.

Technique Description

Determination of resting EF by MRI requires no intravenous contrast agent or stimulant. The protocols that are most commonly used include steady-state free precession (SSFP) and gradient echo sequences, which are discussed in detail in Chapter 13.

RESTING REGIONAL WALL MOTION ABNORMALITIES

Indications and Clinical Utility

Although ventricular EF provides a global assessment of cardiac function, it is still a relatively insensitive index of myocardial pathology. A patient with an EF of 50% may have regional wall motion abnormalities indicative of underlying coronary disease. Because of its excellent spatial resolution, cine MR images of the left ventricle allow a qualitative assessment of regional cardiac function without the acoustic limitations inherent in echocardiography.20 In addition, because the quality and resolution of white blood MR images is not closely related to body habitus or cardiac orientation, images can be acquired in almost any tomographic plane, allowing for a more comprehensive evaluation of regional function.3

Quantitation of regional myocardial function can be accomplished with MRI using a variety of techniques (see Chapter 14). Local wall thickening can be assessed and has been shown to correlate well with the size and extent of myocardial infarction, as measured by enzymatic release.21 Myocardial tagging can also be used to calculate regional strain, an appealing concept because the dynamics of ventricular systole are complex and consist not only of thickening but also of contraction, expansion, twisting, and through-plane motion.20 Strain calculation can potentially detect more subtle wall motion abnormalities than visual qualitative assessment and may provide valuable functional information in patients who have infarctions, hypertension, and nonischemic cardiomyopathies.22–24 It is again worth noting that many of these patients may have a preserved global EF, despite having abnormal segmental myocardial mechanics. Although myocardial tagging and quantification of regional wall function is currently not a routine part of the cardiac MRI examination at most centers, considerable data suggest that it may have significant clinical utility in the future.

Description

Also as for the assessment of global EF, evaluation of regional wall motion abnormalities usually involves SSFP or gradient echo sequences. Although qualitative visual assessment of wall motion is most often used and is often feasible, given the formidable spatial resolution of MRI, quantitation of wall thickening using myocardial tagging may have a more significant clinical role in the future (see earlier, “Indications and Clinical Utility”). Myocardial tagging techniques are discussed in detail in Chapter 13.

RIGHT VENTRICULAR FUNCTION

Indications and Clinical Utility

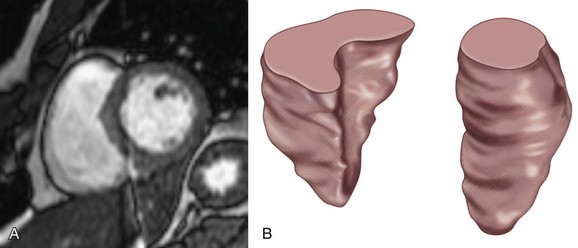

Just as for the left ventricle, RV function has important clinical and therapeutic implications. A depressed RV function predisposes patients to hypotension and confers a poor prognosis for patients with acute myocardial infarctions and chronic LV dysfunction.25 In addition, RV function is a focus of attention in those with congenital heart disease. Because of its geometry and location beneath the sternum, the right ventricle is particularly difficult to assess with echocardiography and radionuclide ventriculography (Fig. 15-1). MRI is not bound by these constraints and thus allows for an accurate assessment of this cardiac chamber.

MRI-derived volumes and mass of the right ventricle have shown robust correlations with in vitro casts and with clinical standards, such as invasive dilution techniques and radionuclide ventriculography.26,27 Studies have also shown high reproducibility, with low intraobserver, interobserver, and interstudy variability in normal volunteers28 and low interstudy variability in a diverse patient population.29 The accuracy and precision of MRI allow for rigorous clinical evaluation of the right ventricle while obviating the risk of invasive procedures and radiation exposure.

DIASTOLIC FUNCTION

Image Interpretation

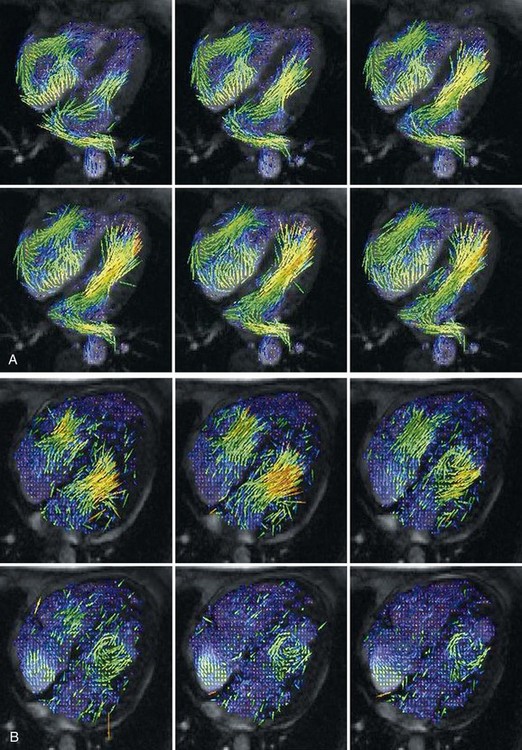

In addition to evaluating the motion and strain of the myocardial tissue, which is currently not widely used clinically for diastole, MRI can also determine LV flow velocities and propagation during diastole. Using phase contrast imaging (see Chapter 17), the transmitral flow pattern can be determined much like it is with echocardiography. It is important to note, however, that some aspects of the transmitral E signal, such as acceleration and deceleration time, have not been validated with phase contrast MRI. Further characterization of diastolic LV flow can be achieved using a combination of phase contrast imaging and color vector mapping (Fig. 15-2). This is an experimental technique at present and is not yet widely used in clinical practice, but it does represent the potential of phase contrast imaging for assessing flow propagation in LV diastole. There is currently no standardized method of reporting diastolic function assessed by MRI.

DYNAMIC LEFT VENTRICULAR FUNCTION USING DOBUTAMINE

Indications and Clinical Utility

Like resting cardiac function, LV response to chronotropic and inotropic stimulation provides considerable clinical information, both physiologic and prognostic. Advances in software and hardware, specifically the development of phased-array surface coils, faster scanning, and advanced gating have increased the practicality and clinical utility of cardiac MRI wall motion stress testing.3 The focus of this subject will be the use of dobutamine and exercise stress testing in clinical practice. See Chapter 53 for a discussion of myocardial contrast perfusion imaging.

Physiology and Safety Profile of Dobutamine

Dobutamine is a synthetic catecholamine with mild β1 receptor selectivity.30,31 It is a positive inotrope and, because of its peripheral vasodilatory effects, it induces a reflex tachycardia.32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

FIGURE 15-1

FIGURE 15-1

FIGURE 15-2

FIGURE 15-2