and Gustavo Marino2

(1)

Attending Physician VA Medical Center, George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

(2)

Chief Gastroenterology Section VA Medical Center, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

8.1.1.1 Anal Canal

8.1.1.2 Rectum

8.1.3 Preparation

8.2.4 Large Colon Polyp

8.2.7 Anorectal Melanoma

8.2.10 Coccygeal Chordoma

Abstract

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) allows a detailed examination of the anal canal, rectum, and adjacent pelvic structures and has become an important tool in the evaluation of colorectal and pelvic disorders. A clear understanding of the anatomy, EUS probe options, and appropriate preparation and technique, as explained in this chapter, is necessary for optimal results.

8.1 General Principles

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) allows a detailed examination of the anal canal, rectum, and adjacent pelvic structures and has become an important tool in the evaluation of colorectal and pelvic disorders. A clear understanding of the anatomy, EUS probe options, and appropriate preparation and technique, as explained in this chapter, is necessary for optimal results.

8.1.1 Anatomy of the Rectal Wall and Perirectal Structures: Correlation with EUS

8.1.1.1 Anal Canal

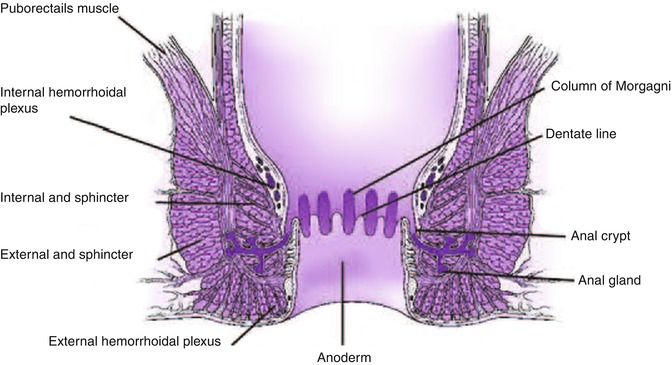

The anal canal extends from the anal verge to the anorectal junction, where the puborectalis encircles the rectum [1]. The dentate line is approximately 2 cm from the anal verge and it is an important landmark to help predict the type of tissue obtained by biopsies and pattern of spread of neoplastic lesions. Anal glands, located mainly at the submucosal space but extending as far as the external anal sphincter, open at the level of the anal crypts above the dentate line. The epithelium appears endosonographically as a faint layer; the submucosa and subcutaneous connective tissue are seen as a well-defined hyperechoic layer. The internal anal sphincter is a caudal extension of the circular inner layer of the muscularis propria of the rectum [1] and can be seen as a hypoechoic circumferential cylinder, approximately 2–4 mm in thickness, in the superior three fourths of the anal canal. The external anal sphincter surrounds the internal anal sphincter below the puborectalis and is formed by striated muscle, appearing as a hyperechoic ring in contrast to hypoechoic smooth muscle layers. The external sphincter is approximately 7–9 mm in thickness in young patients and becomes thinner with age [2, 3]. The anterior portion of the external sphincter is shorter and slopes downward in women, which can lead to a false-positive diagnosis of anterior sphincter tear or defect if the endoscopist is not aware of this normal variation [4].

8.1.1.2 Rectum

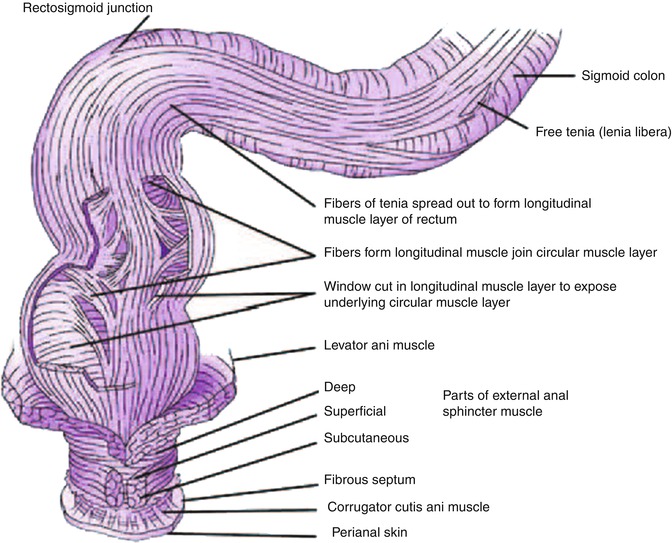

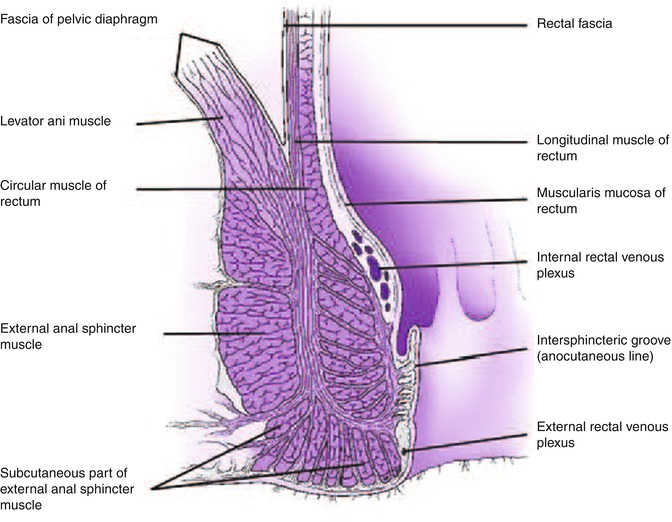

As the probe is advanced proximally from the external sphincter, the puborectalis can be found posteriorly, adjacent to the rectum, appearing as a hyperechoic sling. Additional muscles that form the levator ani have a hyperechoic appearance but are usually not well visualized sonographically.

The rectal wall has a thickness of 2–4 mm. Only the upper third and anterior wall of the middle third of rectum are above the peritoneal reflection and covered by a hyperechoic serosal layer. The posterior peritoneal reflection is approximately 12–15 cm from the anal verge, while the anterior peritoneal reflection is 6–8 cm from the anal verge [1]. The best landmark for the upper border of the rectum is the confluence of the taenia coli at the rectosigmoid junction; however, this confluence cannot be visualized endoscopically; therefore the National Cancer Institute has defined the rectum as the last 12 cm from the anal verge when measured using a rigid proctosigmoidoscope [5]. Three endoluminal curves known as the valves of Houston can be visualized endoscopically. These folds are formed by mucosa and submucosa but not muscularis propria as seen in the partially distended rectum. The middle valve is the most consistently located and is correlated with the anterior peritoneal reflection [1]. The peritoneal reflection is difficult to see sonographically but its limits correlate with the superior margin of bladder in men and superior margin of the uterus and bladder in women [6].

Rectal wall layers seen on sonography include the hyperechoic borderline between the lumen and mucosa, the hypoechoic mucosa, hyperechoic submucosa, hypoechoic muscularis propria, and hyperechoic perirectal fat. The two components of the muscularis propria – circular (internal) and longitudinal (external) – may be identifiable, separated by a thin layer of hyperechoic connective tissue. As mentioned above, only the upper third of the rectum and the anterior wall of the middle third of the rectum as well as the transverse colon and sigmoid are covered by a serosal layer that appears hyperechoic. Retroperitoneal portions of the colon, that is, ascending and descending, are covered by adventitia. The ileocecal valve also has a five-layer pattern but the wall is thickened at that level.

Landmark structures for anatomic reference around the rectum are the prostate, seminal vesicles, and bladder in men and the vagina, uterus, and bladder in women. Flexible endoscopes allow advancement to the distal sigmoid and evaluation of iliac vessels and possible adjacent lymphadenopathy. Pericolonic organs including the liver, pancreas, kidneys, spleen, vascular structures, ovaries (sometimes), and lymph nodes can also be visualized during colonic EUS.

8.1.2 Endoscopic Ultrasound Probes

EUS examination can be performed with rigid probes as well as flexible radial scanning or linear scanning video-endoscopes. Colorectal surgeons and radiologists are more comfortable using rigid probes, but flexible endoscopes are now widely available to gastroenterologists who are trained to use them. Forward-viewing endoscopes allow advancement through the entire colon. Flexible video-endoscopes allow direct optical visualization and confirmation of appropriate scanning or a fine-needle aspiration (FNA) target, avoiding false readings from residual stool. The endoscope can be maneuvered to advance above partially obstructing lesions, and the distance of lesions to the dentate line can be measured [8].

Miniprobe catheters that can be passed through regular endoscope channels also are available. These have a higher scanning frequency (12–20 MHz) and allow detailed evaluation of superficial lesions, particularly those limited to mucosa or submucosa [9].

8.1.3 Preparation

The rectum can be prepared for endoscopy using enemas; two enemas 1 h before the procedure have been reported as appropriate for EUS evaluation of rectal cancer [10]. However, poor preparation and small amounts of stool can interfere with appropriate interpretation, in which case additional enemas may be necessary or, as an alternative, patients can undergo standard colonoscopy preparation [11]. Ideally, patients should avoid urinating before anorectal EUS; this helps to improve bladder visualization. Conscious sedation is not necessary for anorectal EUS unless patients have painful anorectal pathology or painful rectal cancer.

8.1.4 Endoscopic Ultrasound Examination Technique

Endoscopic examination is usually performed first to localize the lesion, evaluate any anatomic distortion to ensure that the echoendoscope can be passed in patients with rectal masses, and evaluate the adequacy of the preparation. If proctosigmoidoscopy is performed it is ideal to minimize air insufflation, and all air should be removed during withdrawal.

To evaluate rectal or colonic lesions the endoscope is advanced and water instilled until the target lesion is covered with water to optimize acoustic coupling; this may require turning the patient so the lesion is placed in the dependent position. Scanning should be performed with the endoscope as parallel to the wall as possible to minimize tangential imaging with magnification of wall thickness. EUS balloons can help examine areas that are not well covered with water; however, caution should be taken not to compress the lesion with the balloon, which might distort staging or measurements.

Evaluation of perirectal lymph nodes requires complete removal of air and careful scanning around the distal sigmoid/rectum, which can be better achieved starting proximally from a point where iliac vessels have been visualized and slowly withdrawing the probe toward the anal canal. An appropriate focal distance should be maintained between the probe and the surface of the rectum or lesion to provide optimal sonographic images.

Adjacent anatomic structures, including the prostate, seminal vesicles, bladder in men and the vagina, uterus, and bladder in women, should be easily recognized. A consistent position of adjacent anatomic landmarks such as prostate or uterus at the top or bottom of the EUS screen allows systematic interpretation and defines the location of the lesions being evaluated. For complete staging in patients with rectal cancer, it is necessary to inspect the iliac vessels, which are usually found between 20 and 25 cm from the anus, and look for perivascular lymph nodes.

Forward-viewing optics are ideal for deeper insertion of echoendoscopes into the colon under direct visualization of the lumen; this is helpful to avoid diverticular perforation or forceful passage. Standard side-viewing echoinstruments, however, also have been used by experienced examiners [12]. The intubation technique is similar to standard colonoscopy but the larger distal end of the endoscope requires more careful manipulation, and it may be more difficult to advance through sharply angulated segments. Bhutani and Nadella [13] have reported no difficulties performing a complete EUS evaluation of up to 45 cm from the anus using radial or linear scanning, oblique view endoscopes. Detailed sonographic visualization of target lesions is better performed during withdrawal of the echoendoscope after water infusion or using the balloon for acoustic coupling.

Examination of the anal canal and sphincters using radial scanning probes without balloon insufflation is usually preferred, although linear scanning instruments have been reported to provide better evaluation of perianal fistulae. Air bubbles can be visualized as hyperechoic tracks or beads at fistulous tracks, and the application of gentle pressure during linear scanning may allow documentation of the air bubbles moving within the track [2]. Greater symmetry of the anterior part of the external sphincter has been achieved during endosonography of the anal canal in the prone position [14].

Box 8.1: Resources for the Colon, Rectum, and Anus

American Joint Committee on Cancer Cancer Staging Manual, 7th edition

National Comprehensive Cancer Network*, Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Rectal and Colonic Carcinoma (2012):

Dave Project – Gastroenterology: EUS for staging of rectal cancer

Medical University of South Carolina, Digestive Disease Center: EUS Atlas

*Registration to the NCCN website is a free service; it is necessary to view these clinical practice guidelines.

Box 8.2: Good Reviews About Anal Cancer

Anal cancer: ESMO Clinical Recommendations for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up (Ann Oncol 2009) http://annonc.oxfordjournals.org/content/20/suppl_4/iv57.long

National Comprehensive Cancer Network*, Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Anal Carcinoma (2013) http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/anal.pdf

*Registration to the NCCN website is a free service; it is necessary to view these clinical practice guidelines.

8.2 Cases and Discussions

8.2.1 Progression of Rectal Cancer from T2N0 to T3N1

Cancer of the rectum, when localized, is a highly treatable and often curable disease. Surgery is the primary treatment and results in cure in approximately 45 % of all patients. The prognosis of rectal cancer is clearly related to the degree of penetration of the tumor through the bowel wall and the presence or absence of nodal involvement. EUS is an accurate method of evaluating tumor stage and the status of the perirectal nodes (detailed discussion in Sect. 8.2.2.1). Accurate staging can influence therapy by helping to determine which patients are candidates for local excision rather than more extensive surgery and for preoperative chemotherapy and radiation therapy to maximize the likelihood of resection with clear margins.

This is a 53-year-old man who was diagnosed with rectal cancer. EUS staging revealed this to be a T2N0 lesion. Unfortunately, he refused standard treatment – despite the urgings of his physicians – and chose alternative treatments instead, which consisted, at least in part, of tea enemas. These were not effective. Four months later he had restaging EUS, which was performed to encourage him to change his mind about treatment. Indeed, the cancer had advanced to a T3N1 stage. Eventually he was convinced to have radiation and chemotherapy.

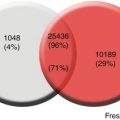

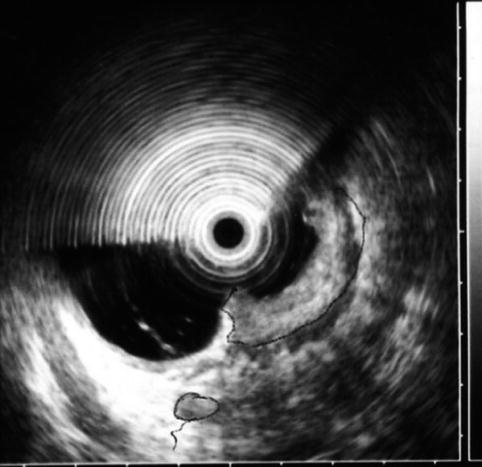

Fig. 8.4

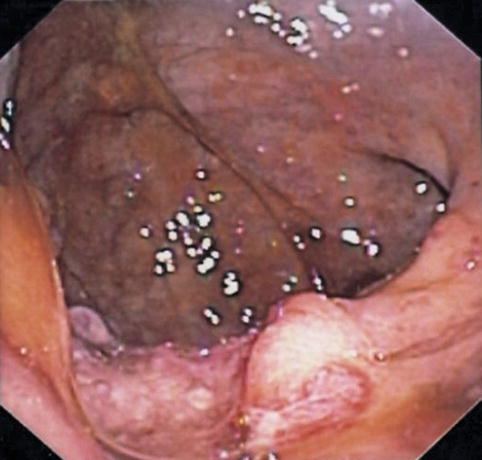

Endoscopic image of a malignant rectal ulcer

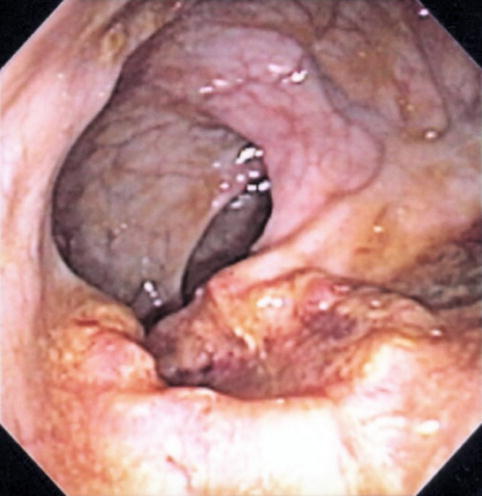

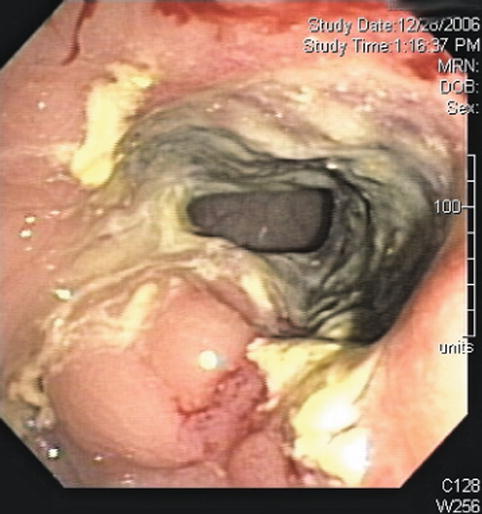

Fig. 8.5

In June, after 4 months of tea enemas, progression of the rectal cancer is seen on endoscopy

Fig. 8.6

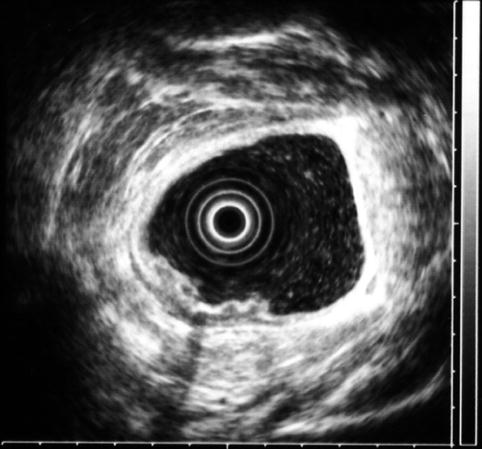

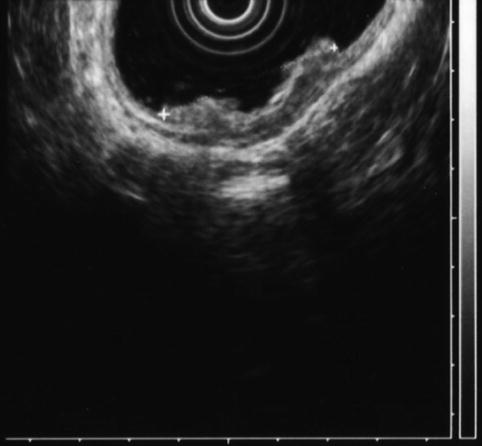

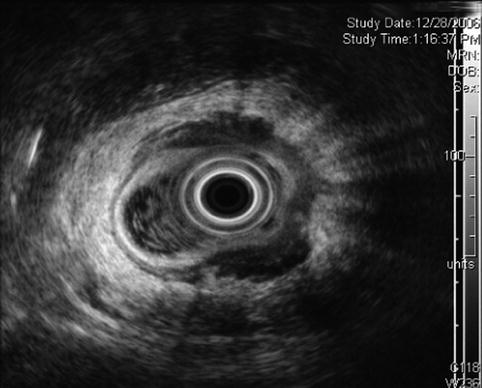

Rectal carcinoma on endoscopic ultrasound (stage uT2N0 at initial presentation)

Fig. 8.7

Another view of the stage uT2N0 rectal cancer

Fig. 8.8

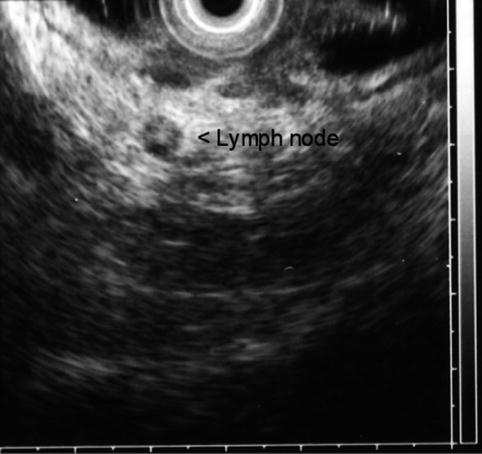

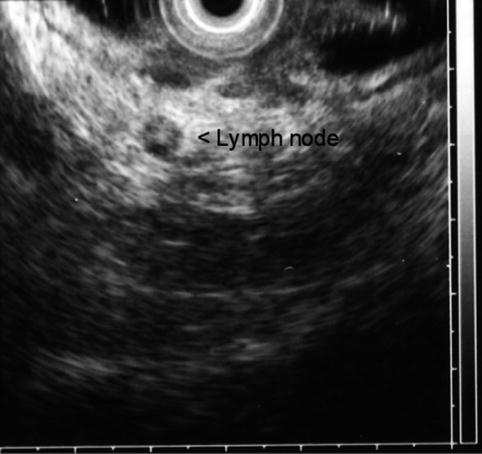

Four months after initial presentation, the rectal cancer has progressed. Malignant lymphadenopathy is now present

Fig. 8.9

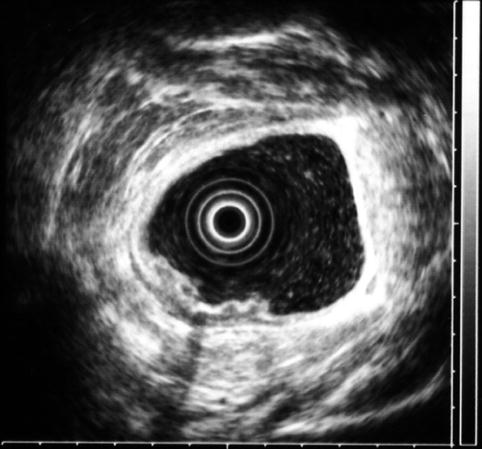

The cancer is now stage T3N1. The tumor penetrates through the muscularis propria (uT3N1)

The histologic T stage of rectal tumors can be estimated sonographically by the deepest layer of visible invasion. The accuracy of EUS evaluation of T stage in the range 69–94 % has been reported [15–17]. Access to the TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) staging system is available online at: http://goo.gl/00RNs.

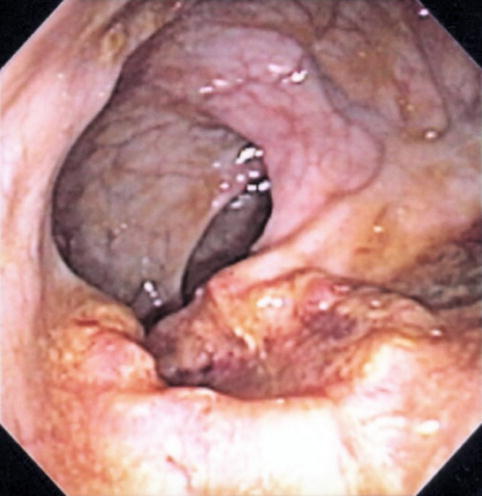

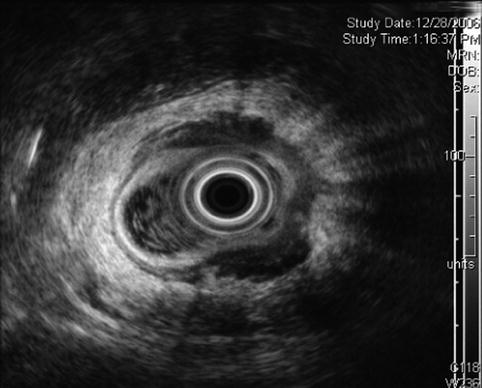

8.2.2 T3N1 Rectal Carcinoma: Response to Treatment

This is a 45-year-old woman with a large, 80 % circumferential rectal tumor associated with lymphadenopathy. She underwent preoperative radiation and chemotherapy, which resulted in the resolution of the previously noted lymphadenopathy and complete disappearance of viable-appearing tumor in the rectum on surface endoscopy. Instead of a tumor a large confluent ulcer is present. Repeat EUS shows a reduction in the size of the hypoechoic mass. It is impossible to tell whether this represents residual tumor, scarring, inflammation, or all three.

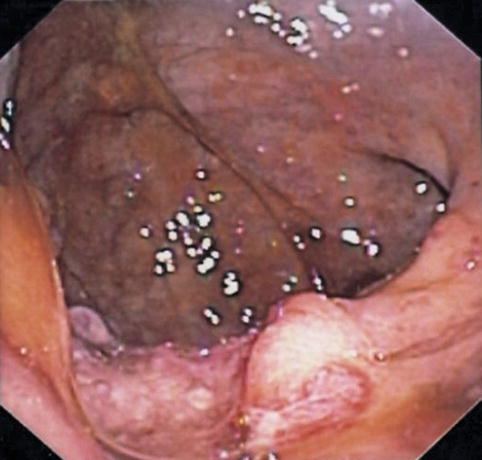

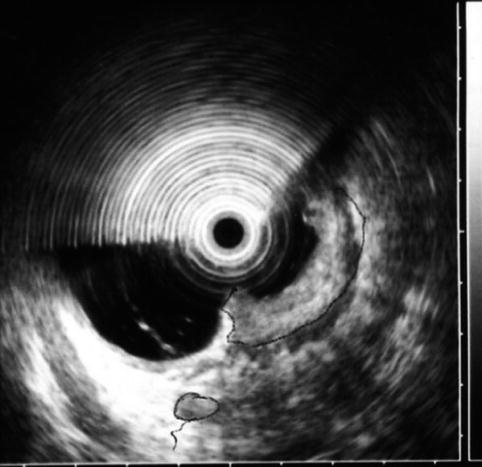

Fig. 8.10

Bulky T3 rectal cancer

Fig. 8.11

Two small, malignant-appearing lymph nodes adjacent to a rectal cancer

Fig. 8.12

Surface endoscopy view of rectal cancer after chemotherapy; ulceration after treatment is seen

Fig. 8.13

Rectal ultrasound after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation

8.2.2.1 EUS for the Evaluation of Rectal Cancer

Appropriate staging of rectal cancer is necessary to plan the best therapeutic approach, for example, the type of surgery, candidacy for anal preserving surgery, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation to prevent local recurrence. The risk of local recurrence after surgery without neoadjuvant therapy is approximately 25 %, mostly during the first 2 years [18]. A relative risk reduction of approximately 50 % of local recurrence has been associated with neoadjuvant chemoradiation in selected patients with stage II and III tumors [19]; EUS is one of the most accurate modalities in the assessment of the extent of local tumors [20]. Evaluation of sphincter involvement is also provided by EUS and is important in patients with distal tumors. Other imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been used for this purpose. CT provides information regarding distant metastasis but has limited capacity to distinguish mural layers and local depth of invasion. MRI with dedicated coils has an accuracy similar to that of EUS, and it may have an advantage for more advanced lesions [21].

Features that may cause artifacts, including poor preparation, presence of air within tumor ulcerations, previous biopsy or electrocautery defects, previous surgery or radiation, and tangential imaging, should be considered.

EUS can be helpful to evaluate for signs of deep wall invasion, which will determine potential minimally invasive resectability [10], in cases with suspected but unconfirmed malignancy.

Hildebrandt et al. proposed a modification of the TNM system based on EUS findings, adding the prefix u, indicating the use of ultrasonographic criteria, as opposed to the prefix p, which is used for pathologic postoperative stage. Of course, distant metastases cannot be evaluated by EUS, and therefore only T and M are included in staging [22].

Early stage rectal tumors (uT1: confined to submucosa) without evidence of regional metastasis to lymph nodes are ideal candidates for local excision, transanal surgical resection, or transanal endoscopic microsurgery [23] and are associated with less morbidity than radical surgery [24]. Local recurrence for T1 adenocarcinomas is relatively low: 9.8 % at 5 years.

uT1 and uT2 lesions are usually appropriate for surgery without neoadjuvant chemoradiation. uT3 tumors extend to the serosa or perirectal fat, and uT4 lesions invade adjacent organs including the prostate, seminal vesicles, vagina, uterus, or bladder. T3 and T4 lesions are considered locally advanced and are usually treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiation, which can reduce the risk of local recurrence and provide better patient tolerance [25].

Deep invasion of the wall beyond muscularis propria or evidence of regional lymph node metastasis is associated with a higher local recurrence (up to 40 %) [26]. Preoperative chemoradiation for T3 or N1 tumors has been shown to decrease the relative risk of postoperative local recurrence to approximately 50 % compared with those that did not receive neoadjuvant therapy [19].

Early extension through the muscularis propria (T3) may be difficult to differentiate from adjacent inflammatory or desmoplastic reactions (histologically T2) using ultrasound because these pseudotumorous changes are also hypoechoic and indistinguishable from true neoplasm. This problem can lead to overstaging in up to 18 % [15, 27] and understaging in up to 13 % of tumors [15].

Whether T staging is more difficult after polypectomy because of inflammatory changes is debatable; changes after polypectomy are not expected to cause sonographic changes beyond the rectal wall, and demonstration of disease at this level is considered accurate in diagnosing tumor extension [28]. Overall accuracy of T staging by EUS has been reported between 72 and 92 % [29].

The risk of lymph node metastasis correlates with the depth of invasion; it has been reported in 6–11 % of T1, 10–35 % of T2, and 25–65 % of T3 and T4 tumors [30, 31]. Sonographic criteria for nodal staging of rectal cancer are limited. The typical criteria for suspicion of metastatic lymph nodes developed in the staging of esophageal cancer by EUS include size greater than 1 cm, round shape, and hypoechoic sonographic pattern without hyperechoic core. Unfortunately, these criteria have limited sensitivity and specificity in rectal cancer. The accuracy of diagnosis by ultrasound without FNA has been reported between 64 and 85 % [15, 16, 29], leading to overstaging in up to 25 % and understaging in 11 %. Normal perirectal lymph nodes are usually less than 3 mm in diameter and not visible by EUS; however, up to 78 % of lymph nodes ≤ 5 mm in diameter identified by EUS have been found to have metastatic invasion [32]. Enlargement of lymph nodes > 5 mm is not sufficient to diagnose malignant invasion; metastatic lymph nodes overlap in size with peritumoral inflammatory nodes.

Staging can be improved by performing FNA to confirm nodal or distant metastases [33]. FNA of nonjuxtatumoral lymph nodes has been shown to change therapy in 19 % of patients, particularly in those with early T stage disease. Accuracy of EUS with FNA for nodal staging was 92 % in a study by Shami et al. [29].

One study found that EUS-guided FNA of solid lesions of the lower gastrointestinal tract, including lymph nodes, had a low risk of infections and complications [34]; these authors did not consider EUS-guided FNA a standard indication for antibiotic prophylaxis.

MRI with endorectal coils visualizes the rectal wall very well; however, this technique may be challenging because of difficulty inserting the coil in patients with a stenosing tumor, poor visualization of lesions high in the rectum, and poor resolution of structures surrounding the rectum. MRI with pelvic phased-array coil is noninvasive and allows the entire pelvis to be visualized but has lower resolution of the rectal wall. Some authors have found that MRI is more accurate in the staging of locally advanced tumors [21, 35], whereas EUS can quite accurately stage T1 and T2 tumors. Accuracy of nodal staging by MRI has been reported between 59 and 95 %, similar to that of EUS without FNA. Therefore, MRI and endorectal ultrasound are considered complementary methods in the preoperative staging of rectal cancer [35], and EUS offers the possibility of FNA/histologic diagnosis in patients with suspected imaging.

EUS can also detect recurrent cancer at or near the anastomosis line, which is frequently not detectable by colonoscopy, carcinoembryonic antigen level, digital exam, or other imaging techniques [36]. Many of these lesions arise extraluminally and are not detectable with standard videoendoscopy until they are at an advanced stage. Prospective studies have shown that EUS is superior to CT for detection of recurrent rectal cancer [37, 38]; CT images are frequently distorted by surgical changes, metal clips, or radiation. Lesions smaller than 2 cm diameter may not be accurately detected by CT [2]. Recurrent cancer has been described on EUS as a hypoechoic mass involving a portion of the rectal wall, typically at or just above the site of resection anastomosis [25]. EUS-guided biopsy may be necessary to establish the final diagnosis because similar findings may be due to surgical scarring or radiation. EUS in combination with FNA of suspicious lesions has been shown to have an accuracy of at least 92 % in the detection of early recurrence, leading to curative resection [38, 39]. Surveillance with EUS every 6 months for 2 years after low anterior resection or transanal excision has been recommended by some experts [40]. This aggressive approach is more likely to benefit those with a high risk of recurrence, such as patients with more advanced tumors at diagnosis or those undergoing local excision [2].

8.2.3 Colon Cancer Metastatic to Mediastinal Lymph Nodes

The liver, lungs, bones, peritoneum, and lymph nodes are metastatic sites of colon cancer. Mediastinal lymph nodes are rarely affected. This is a 69-year-old patent who had a transverse colectomy for colon cancer 18 months earlier, the final pathologic stage of which was T3N2. Recent follow-up positron emission tomography showed activity in the right hilar and subcarinal lymph nodes. EUS could not demonstrate the right hilar mass. However, the relatively small subcarinal lymph nodes were aspirated under EUS guidance and found to be positive for metastatic adenocarcinoma, most consistent with a colonic primary tumor.

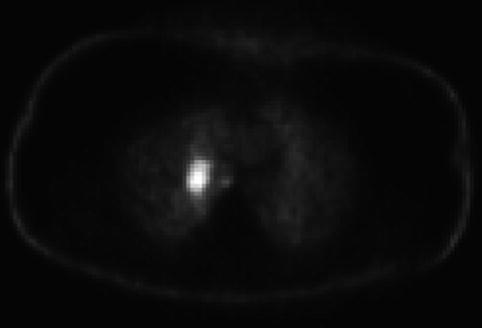

Fig. 8.14

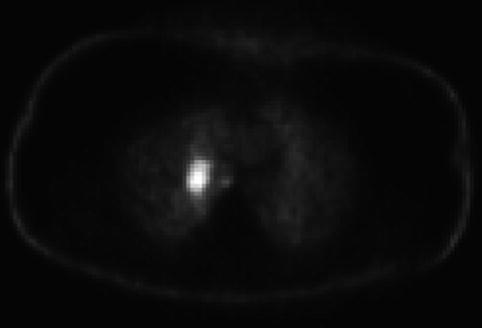

This positron emission tomography scan shows activity in the right hilar area

Fig. 8.15

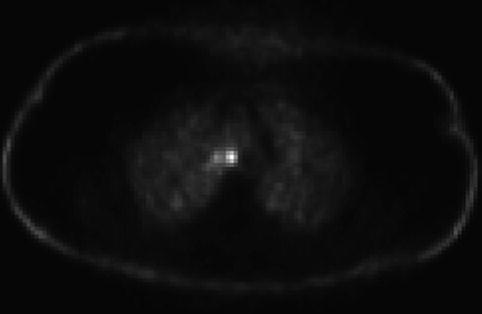

This positron emission tomography scan shows additional smaller and less intense hot spots in a subcarinal location

Fig. 8.16

This positron emission tomography scan shows diffuse nonspecific activity throughout the colon. A right hilar hot spot can also be appreciated

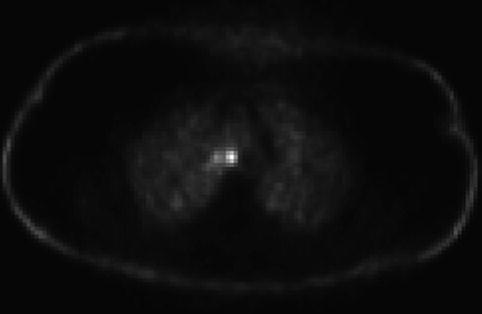

Fig. 8.17

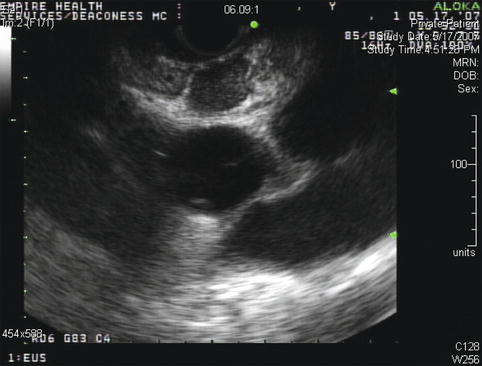

Endoscopic ultrasound appearance of the mildly enlarged subcarinal lymph nodes before fine-needle aspiration biopsy

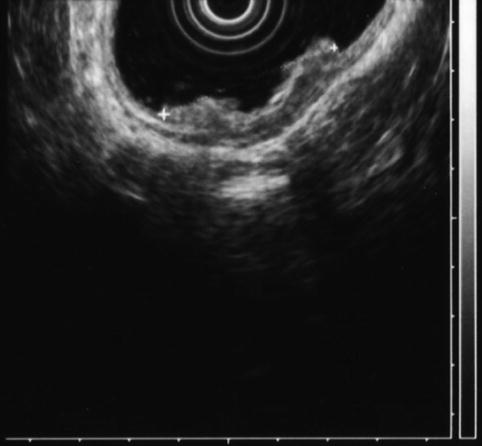

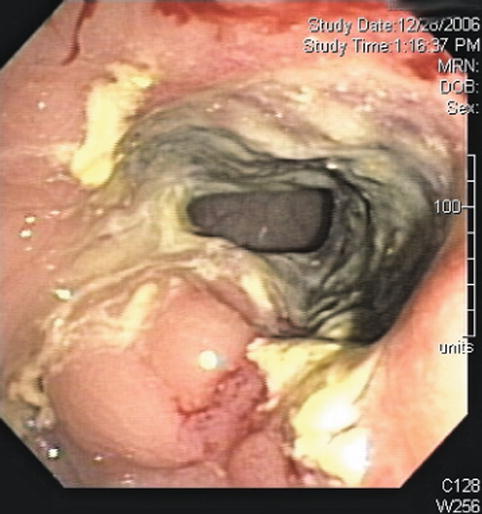

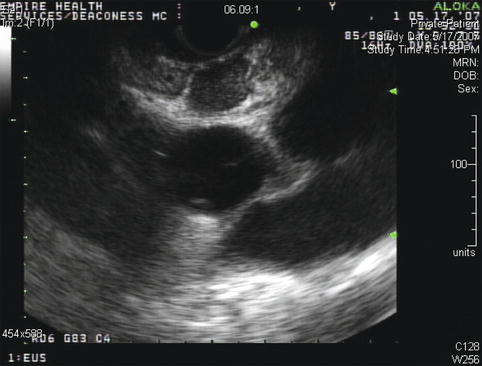

8.2.4 Large Colon Polyp

This is an 83-year-old patient with rectal bleeding. Colonoscopy showed a 4-cm-diameter mobile polypoid mass located at the rectosigmoid junction. Biopsies revealed high-grade dysplasia, probably reflecting sampling error. An endorectal ultrasound was performed, revealing a large polypoid tumor with a short stalk and no evidence of invasion that was suspicious foci or lymphadenopathy. Given the patient’s age, we recommended a snare polypectomy as a reasonable choice and that further management would depend on the extent of stalk invasion (if any).