CHAPTER 7 Computed Tomography Incidentalomas

The discovery of small, incidental, asymptomatic lesions during the routine review of computed tomographic (CT) images is a common and often frustrating occurrence in routine clinical practice. Such lesions are often referred to as indeterminate, nonspecific, or “too small to characterize.” Because most busy radiologists cannot devote more than a brief moment to determining the significance and subsequent evaluation of such lesions, this section is dedicated to “incidentalomas.” We do not advocate a single approach to small incidental lesions because recommendations remain in flux. Each individual radiologist must determine the degree of uncertainty he or she is willing to tolerate, taking into consideration patient anxiety and prognosis, the personality and typical practices of the referring physician, and the number of malpractice attorneys preying on the local medical community. Regardless, one should always use common sense. If a lesion has a small chance of being malignant, recommending further costly or potentially morbid tests is of no immediate benefit to a patient with significant comorbidities of an acutely life-limiting nature. Likewise, incidental lesions should not be viewed as an opportunity for revenue building through the recommendation of frequent follow-up imaging studies. In contrast, with the increasing availability of minimally invasive therapies for malignant tumors, early detection and diagnosis of incidental malignant neoplasms has taken on new imperative.

LIVER

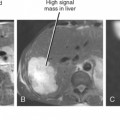

Patients with No Known Cancer or Chronic Liver Disease

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has the highest sensitivity and specificity of available hepatic imaging techniques but is typically reserved for the evaluation of patients with risk factors for malignant tumor or infection. MRI is capable of distinguishing between benign and malignant lesions in the majority of cases referred for a small indeterminate lesion discovered with CT. However, MRI is costly and should be reserved for cases when further characterization of a lesion is likely to affect patient management. Such situations include oncology patients for whom hepatic resection or an alternate chemotherapy regimen is contemplated.

Patients with Known Extrahepatic Cancer

Even in patients with known primary malignancy, a small incidental lesion discovered with CT is more likely benign than malignant (Fig. 7-1). In patients with known primary cancer, a lesion considered “too small to characterize” by CT has a greater than 80% chance of being benign according to most studies. The actual number can be expected to vary with the population studied, the criteria used to define small or “too small to characterize,” the imaging technique, and the interpreting individual. Patients with breast cancer with one or more small (≤15 mm) hypoattenuating lesions on a baseline contrast-enhanced CT scan without other evidence of hepatic metastases are no more likely to experience development of subsequent hepatic metastases than patients with no such lesions. In another study of patients with breast cancer, too small to characterize lesions represented benign findings in more than 90% of women. Patterson and researchers studied the MRI evaluation of “too small to characterize” liver lesions discovered with CT in patients with breast cancer and found that only 5% of such lesions were shown to represent metastases. In a study of hepatic lesions 15 mm or smaller in patients with gastric and colorectal cancer, almost 80% were benign. In that study, if patients with larger coexistent liver metastases were excluded, small hypoattenuating lesions were metastases in only approximately 2% of patients.

Patients with Chronic Liver Disease

Patients with chronic viral hepatitis or cirrhosis are at increased risk for development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Unfortunately, patients with chronic liver disease are also likely to be plagued by small, incidental, arterially enhancing lesions on dynamic, multiphase, contrast-enhanced imaging. The cause of such lesions varies and may include arterial-portal shunt, regenerative nodule, or benign neoplasm (e.g., hemangioma or focal nodular hyperplasia–like lesions). Fortunately, small (<2 cm), arterially enhancing nodules not visible on other phases of enhancement are more likely to be benign than malignant in the setting of chronic liver disease, although it may be difficult to distinguish benign nodules from hepatocellular carcinoma based on imaging criteria alone. Therefore, patients with chronic liver disease who have small arterially enhancing nodules on dynamic, multiphase, contrast-enhanced CT (or MRI) are usually followed with CT or MRI at approximately 6-month intervals. Small, arterially enhancing lesions that demonstrate intralesional washout of contrast material during the portal venous phase, a nodule-within-nodule appearance, rim enhancement, or evidence of a pseudocapsule on portal phase images should be considered malignant until proved otherwise.