Congenital Malformations

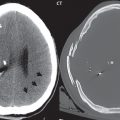

MR is the modality of choice for evaluation of all congenital malformations of the brain, with the exception of the craniosynostoses. In individual instances, some findings may be apparent on CT, with it thus being important to keep in mind the congenital malformations of the brain when interpreting CT.

Posterior Fossa Malformations

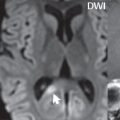

In a Chiari I malformation, there is displacement of the cerebellar tonsils > 5 mm below the level of the foramen magnum. This abnormality is not uncommon, and usually asymptomatic. On sagittal images the cerebellar tonsils are pointed or wedge-shaped ( Fig. 1.10 ). The fourth ventricle will be in normal position. Symptoms occur when there is obstruction of CSF flow through the foramen magnum. If there is crowding at the level of the foramen magnum, CSF flow studies can be obtained on MR to determine if the flow is abnormal and thus likely to contribute to symptoms (most frequently headache) ( Fig. 1.11 ). In symptomatic cases, there can be dilatation of the central canal of the spinal cord, specifically hydromyelia (more generally termed syringohydromyelia). Treatment is surgical, by suboccipital decompression with resection of the posterior arch of C1.

A Chiari I malformation is to be distinguished from tonsillar ectopia, specifically mild inferior displacement of the cerebellar tonsils seen in asymptomatic normal individuals. In this entity, the tonsils retain their normal globular configuration. In most normal individuals, the tonsils lie above the level of the foramen magnum, but they may lie as far as 5 mm below and still be normal.

The Chiari II malformation is a complex congenital brain anomaly, which involves principally the hindbrain (the medulla, pons, and cerebellum). Additional features involve the forebrain (the cerebral hemispheres, basal ganglia, and thalamic structures). In patients, a Chiari II malformation is associated with a neural tube closure defect in almost 100% of cases, usually a lumbosacral myelomeningocele. Characteristic features of a Chiari II malformation are subsequently described, not all features need be or are commonly present ( Fig. 1.12 ).

By definition, there will be a small posterior fossa with low insertion of the tentorium. The tentorial incisura may be widened, allowing the cerebellum to extensive superiorly, a “towering cerebellum.” In this instance the folia of the cerebellum will have a vertical orientation. In a small number of cases the cerebellar hemispheres extend more anteriorly than normal, forming on an axial image the appearance of three bumps, the middle being that of the pons. The fourth ventricle is typically elongated (slit-like) and inferiorly displaced. A ballooned fourth ventricle is seen in 10%. Another defining feature is inferior displacement and elongation of the brainstem, tonsils, and vermis. The degree of displacement is often substantial. Cervicomedullary kinking, overlapping of the medulla and cervical cord, may occur. There may be an enlarged foramen magnum and upper cervical canal, accompanied by a smaller C1 ring, with resultant compression of displaced brainstem, tonsils, and vermis at this level. Cervical (and thoracic) syringohydromyelia is common. Obstructive hydrocephalus is usually present, with most patients shunted. Callosal dysgenesis (usually partial agenesis of the corpus callosum) is seen in 75%. Fusion of the colliculi, “tectal beaking,” is seen in the majority. The frontal horns may have a characteristic inferior pointing seen on coronal images. The massa intermedia is typically large. There is often hypoplasia or fenestration of the falx, with interdigitation of cerebral gyri. Stenogyria (multiple small cerebral gyri) is common. A Chiari III malformation is rare, with features of the Chiari II malformation together with a low occipital or upper cervical encephalocele.

In a Dandy-Walker malformation, there are three primary features. The posterior fossa is large, with the confluence of the sinuses/torcula high in position. Additionally, there is a large posterior fossa cyst that communicates with the fourth ventricle anteriorly. The third defining feature is vermian and cerebellar hemisphere hypoplasia, which can be present to a varying degree ( Fig. 1.13 ). On sagittal images, the residual vermis may be rotated superiorly (counterclockwise). The occipital bone may be scalloped and thinned. Imaging in the sagittal plane is essential for definition of the structural abnormalities. There is a spectrum of severity of findings, and thus the additional use, in the past, of the terms Dandy-Walker continuum and Dandy-Walker variant. The term Dandy-Walker spectrum has also been suggested more recently, specifically including mega cisterna magna as the entity with the mildest findings.

A mega cisterna magna is an enlarged CSF space posterior to the cerebellum, without mass effect, and with the cerebellar hemispheres, vermis and fourth ventricle specifically normal. These are common, and considered to be incidental findings. The primary differential diagnosis is a retrocerebellar (posterior fossa) arachnoid cyst. Although by definition there will be mild compression of the cerebellum, and scalloping of the calvarium may be present, most retrocerebellar arachnoid cysts are also asymptomatic. Like all arachnoid cysts, however, a discrete membrane separating the cyst from adjacent normal CSF is rarely seen on imaging. Retrocerebellar arachnoid cysts are most common along the midline. The size of the posterior fossa and position of the tentorium and straight sinus are usually normal, with the cerebellar vermis and hemispheres intact.

Cortical Malformations

Hemimegalencephaly is defined by hamartomatous over-growth of a hemisphere. The lateral ventricle on the abnormal side is often large. Abnormalities of the brain on the side of involvement are common and include a thickened cortex and abnormal white matter signal intensity.

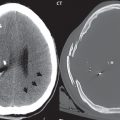

In heterotopic gray matter, there are displaced masses of gray matter, found anywhere from the embryologic site of development (periventricular) to the final destination after cell migration (cortical). The most common presentation is that of small focal regions of gray matter adjacent to the lateral ventricles ( Fig. 1.14 ). Important for diagnosis is that these small focal lesions are isointense to gray matter on all MR pulse sequences. The primary differential diagnostic consideration is tuberous sclerosis, specifically the subependymal nodules therein. The latter may demonstrate calcification, with the cortical involvement in tuberous sclerosis an additional differentiating feature. Less common forms of heterotopic gray matter include large nodular lesions and band heterotopia.

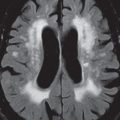

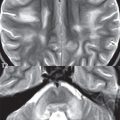

Lissencephaly type 1 or classic lissencephaly (previously known as the pachygyria-agyria complex) is a disorder of cortical formation, with arrested neuronal migration. On imaging, there is a thickened cortex, a smooth brain surface, a small number of shallow sulci, and decreased peripheral arborization of white matter ( Fig. 1.15 ). Histologically there is a four-layered cortex (as opposed to the normal six layers). On a T2-weighted scan, a hyperintense cell sparse zone may be recognizable, separating a thin gray matter cortical ribbon from a thicker underlying gray matter layer containing disorganized neurons. Incomplete lissencephaly ( Fig. 1.15 ), with focal areas of pachygyria (and otherwise normal brain), is much more common than complete lissencephaly.

Lissencephaly type 2, also known as cobblestone lissencephaly, is a distinct, separate entity from lissencephaly type 1. In type 2, there is a nodular or “pebbly” appearance to the brain surface, with broadened gyri and loss of sulci (thus the term lissencephaly). There are commonly associated ocular anomalies, with this entity usually occurring as part of a congenital muscular dystrophy. The brain is small and the cerebral white matter reduced in volume.

In polymicrogyria, an abnormality involving late neuronal migration, there are multiple small gyri along the brain surface ( Fig. 1.15 ). Due to their very small size, these may not be visualized on MR. The resultant imaging appearance is that of a focal region of brain with an irregular cortical surface, a thick layer of gray matter (cortex), and subtle irregularity at the gray–white matter interface. There will be a decreased number of gyri, with the visible gyri being broad, thick, and relatively smooth. The involvement can be unilateral, bilateral, symmetric, or asymmetric. A perisylvian location is common. Anomalous venous drainage, often a large draining vein located in a deep sulcus, is common in regions of dysplastic cortex. On histology, in polymicrogyria, there is a derangement of the normal six-layered cortex.

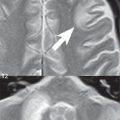

Schizencephaly is characterized by the presence of a gray matter lined cleft, which extends from the cortex to the ventricular system. Schizencephaly can be either unilateral or bilateral. There is a spectrum of appearance, in terms of separation of the gray matter lined walls, from closed to open lip ( Fig. 1.16 ). A dimple in the wall of the ventricle can be an important clue for recognition of the closed lip form ( Fig. 1.17 ).

The septum pellucidum is commonly absent. MR is markedly superior to CT for detection of the gray matter lined cleft and associated abnormalities. Identification of the gray matter lining is important to differentiate schizencephaly from porencephaly. In the latter, there is an abnormal CSF space, due to destruction of brain, which can communicate with the ventricle but is not lined by gray matter. Porencephaly is caused by a vascular accident during the third trimester of fetal development, and as such often abuts the ventricle, with an intervening intact ependyma. The term porencephaly has also been used more generally to include any non-neoplastic cavity within the brain, not specifically in utero in etiology, including vascular insult, trauma, infection, and surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree