Clinical criteria

Immunologic criteria

1. Acute cutaneous lupus

1. ANA

2. Chronic cutaneous lupus

2. Double-stranded DNA

3. Oral or nasal ulcers

3. Anti-SM

4. Non-scarring alopecia

4. Antiphospholipid antibody

5. Arthritis

5. Low complement (C3, C4, CH50)

6. Serositis

6. Direct Coombs test (do not count in the presence of hemolytic anemia)

7. Renal

8. Neurologic

9. Hemolytic anemia

10. Leukopenia

11. Thrombocytopenia

Musculoskeletal System

Musculoskeletal involvement is one of the most common manifestations of SLE with an incidence ranging from 65 to 95 %. Arthritis is characterized as migratory, with associated swelling almost similar to that of rheumatoid arthritis involving the wrists, metacarpophalangeal (MCP), interphalangeal, (IP) and knee joints. Generally they are nondeforming and nonerosive; however, about 5–15 % may develop a deforming arthropathy (Fig. 7.1).

Fig. 7.1

A 49-year-old female with systemic lupus erythematosus, AP radiograph shows subluxations at the second to fifth MCPJs and Jaccoud’s arthropathy. Features were bilateral and symmetrical. Note also swan neck deformity thumb, periarticular prominence of a generalized osteopenia. This patient also had clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis; note the periarticular erosion on the radial margin second metacarpal head. Erosions are rarely reported in SLE, and if present an alternate diagnosis or a second arthritis should be considered as in this case

Jaccoud’s arthropathy is a classic example of a deforming arthropathy related to ligament and tendon laxity resulting from capsular and periarticular fibrosis and synovial vasculitis. The interplay of inflammatory cells and the presence of cytokines such as IL1 and IL6 play a role in its pathogenesis. Radiographic feature reveals joint deviation with MCP joint subluxation and ulnar deviation without erosions involving the second to fifth MCPJ. This was initially described in patients post-rheumatic fever but is now more commonly seen in SLE and mixed connective disease. In addition, reversible swan neck deformity of the thumb may be present, hyperextension at the IP joint, and flexion at the MCP joint.

In patients with erosive features, this may be related to Rhupus syndrome whereby the patient has clinical features of SLE overlapping with rheumatoid arthritis (Fig. 7.1). Rhupus patients initially present with characteristics that of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) but later on present with clinical and laboratory features of SLE. Hormonal factors may play a role in its pathogenesis. Biomarkers of RA such as rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP (anti-citrullinated peptide) are also noted. Rhupus arthropathy is a symmetrical polyarthritis which could lead to debilitating deformities. Radiographic features may show marginal erosions similar to that in rheumatoid arthritis. Dystrophic soft tissue calcification (Fig. 7.2) may occur with skin and periarticular deposition. Imaging findings are reviewed in detail in Chap. 16. Ultrasound features include synovial hypertrophy, joint effusion, and erosions. Tenosynovitis and tendinosis may be present and is related to an increased risk of tendon rupture (Fig. 7.3). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides optimal images for bone edema, erosions, and soft tissue involvement such as capsular swelling, synovial hypertrophy, and tenosynovitis (Fig. 7.4).

Fig. 7.2

A 34-year-old female systemic lupus erythematosus demonstrating soft tissue calcification on the volar aspect on the 1st interphalangeal joint

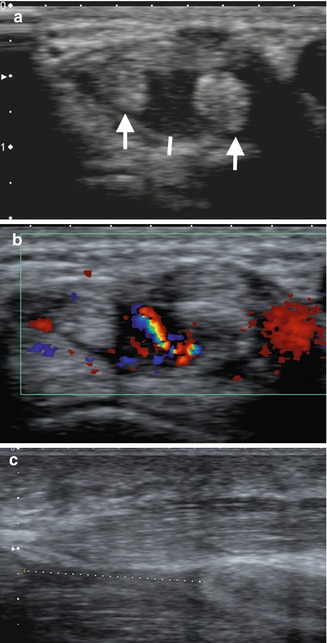

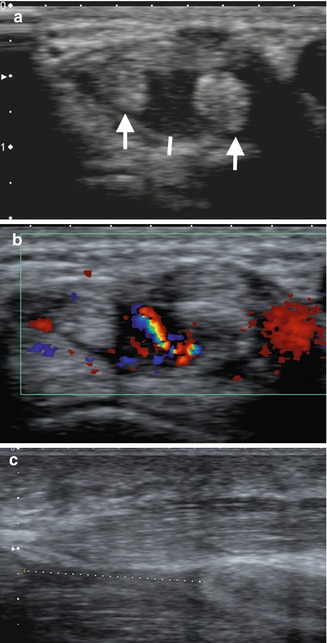

Fig. 7.3

A 42-year-old female with long-standing SLE presenting with acute tenosynovitis, (a) transverse ultrasound dorsal wrist, fourth extensor compartment, with enlarged tendons with heterogeneous echotexture (arrows) and tendon sheath distension (line); (b) marked increased flow within the tendon sheath in keeping with active synovitis; and (c) different patient with rupture flexor pollicis longus tendon, separated tendon ends indicated by a dashed line

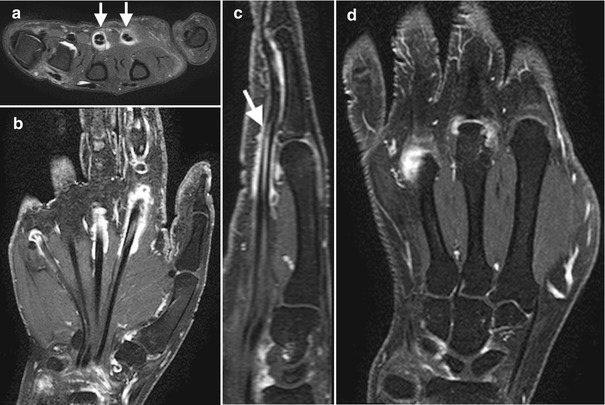

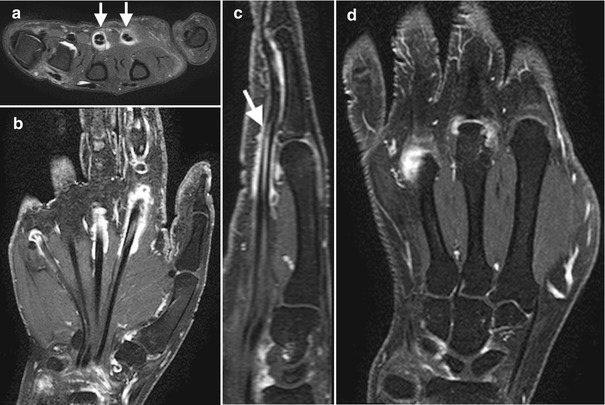

Fig. 7.4

A 62-year-old female with systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with persistent left hand pain. Multiplanar MRI imaging sequences including post-gadolinium study. (a) Axial T2FS reveals diffuse to moderate second and third common flexor tenosynovitis (arrows) and mild effusion at the fourth metacarpophalangeal joint. (b) Cor T1FS PG demonstrates enhancement of the second, third, and fifth common flexor sheath (tenosynovitis) and (c) third flexor tenosynovitis (arrow) on Sag T1Fs. (d) Cor T1FSPG demonstrates active synovitis at the third and fourth MCPJs and periarticular erosion of the third metacarpal head

Osteonecrosis is defined as “bone death” resulting from arterial blood supply compromise. It affects about 13 % of patients, usually involving the femoral head, humeral head, tibial plateau, and scaphoid. The patient may be asymptomatic or may develop vague pain on joint movement or sudden severe pain over the affected joint due to collapse. Corticosteroid use may be the most common etiology; however, vasculitis, embolic phenomenon, and antiphospholipid syndrome are possible etiologies. Imaging features of osteonecrosis are reviewed in Chap. 12.

Myalgia is a common manifestation of SLE. Myositis is less common, 7–15 %. Proximal muscle weakness is the usual manifestation associated with elevated muscle enzymes, and EMG findings of spontaneous fibrillations, positive potentials, small amplitude, polyphasic potentials, and repetitive high frequency potentials are seen similar to patients with polymyositis. Biopsy findings include interstitial inflammation, fibrillar necrosis, and degeneration. MRI findings reveal hyperintense signal in myositis on T2, which may enhance post gadolinium.

Central Nervous System (CNS) and Peripheral Nervous System (PNS)

CNS and PNS involvement in SLE may present in different patterns which includes seizures, psychosis, aseptic meningitis, stroke, myelopathy, and neuropathy. Diagnoses and treatment has been a challenge, and determining the immunopathology of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (NPSLE) is restricted due to reluctance in doing brain biopsies. Biopsies however have been the gold standard with pathology demonstrating necrosis of the vasculature, disruptions of the elastic lamina, with inflammatory cell infiltration, and the presence of thrombi. Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation, spinal fluid analysis, serum biomarkers, as well as imaging. I will be outlining more of the neurologic rather than the psychiatric imaging in NPSLE.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging is more sensitive and the most useful imaging for both cerebrovascular and spinal pathologies. Small vessel cerebrovascular involvement in NPSLE shows white matter lesions and periventricular hyperintensities on T2. T2 FLAIR provides greater conspicuity of lesions. T1-weighted sequences may be normal or demonstrate subtle hypointensity. Periventricular lesions are noted to be associated with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). This however may mimic many other white matter diseases, and findings have to be reviewed in the correct clinical context (Fig. 7.5). Enhanced studies may be beneficial in differentiating between acute and chronic lesions. Due to rapid reversibility of some of these lesions at times, prompt timing of imaging is crucial. Reversible neurologic deficits may also be present in SLE and may reveal T2-weighted sequences of demyelination in the periventricular areas, corpus callosum, and cerebellar area. Hemorrhage may also occur. Large vascular infarcts are less common and occur in a vascular territory. MRI best delineates the extent of involvement with high SI on T2 and restricted diffusion in the acute stage. PRES, posterior reversible encephalopathy, present with hypertension, headaches, and neurologic symptoms related usually to the posterior circulation. MRI is the diagnostic study of choice and demonstrates reversible high SI lesions of the parietal and occipital lobes (Fig. 7.6). Occasionally infarction may occur. Patients with antiphospholipid syndrome in particular may develop venous thrombosis of the venous sinuses and deep cerebral veins.

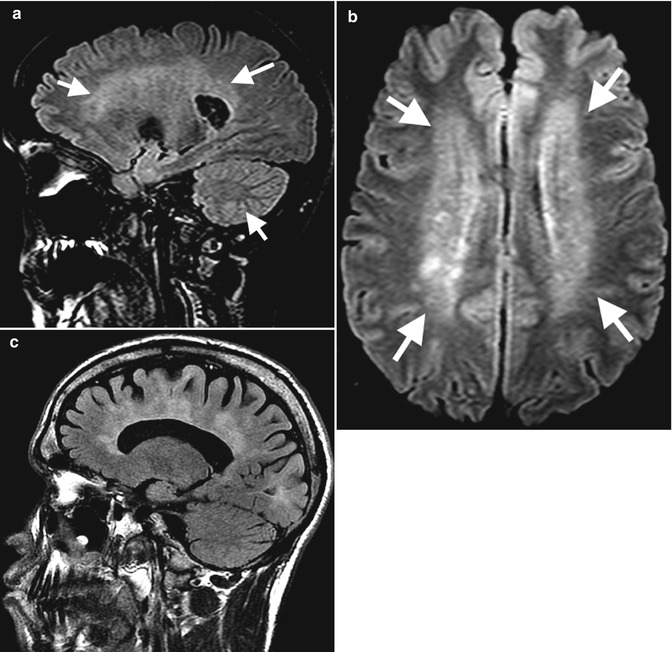

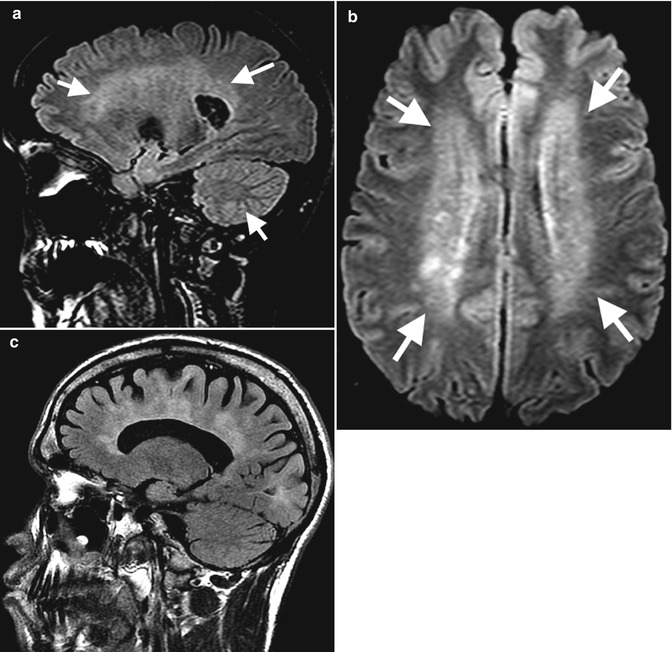

Fig. 7.5

A 29-year-old female with SLE cerebral vasculitis (a) sagittal and (b) axial T2 FLAIR demonstrates periventricular and deep white matter high signal intensity (arrows). Note that imaging findings need correlation with clinical picture. Similar findings in patient with multiple sclerosis (c)

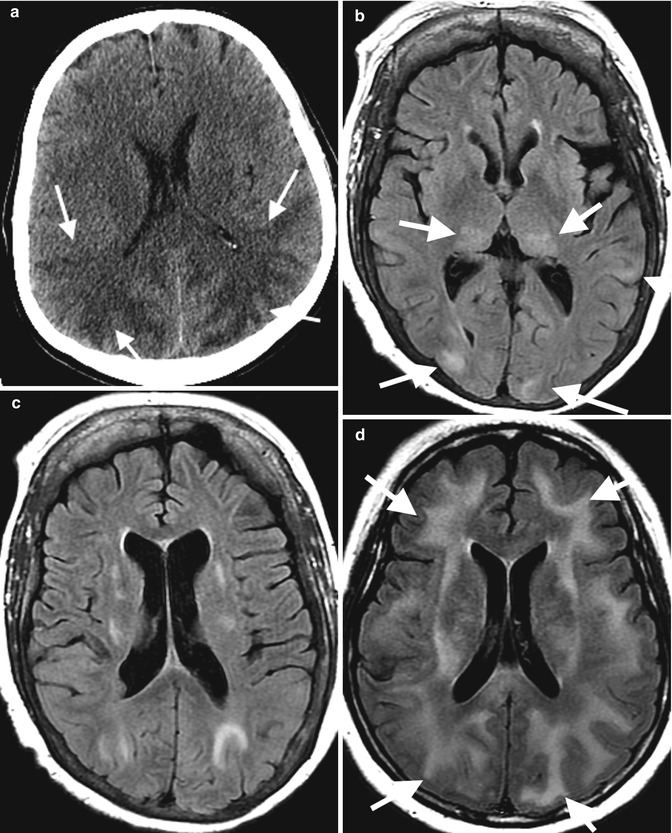

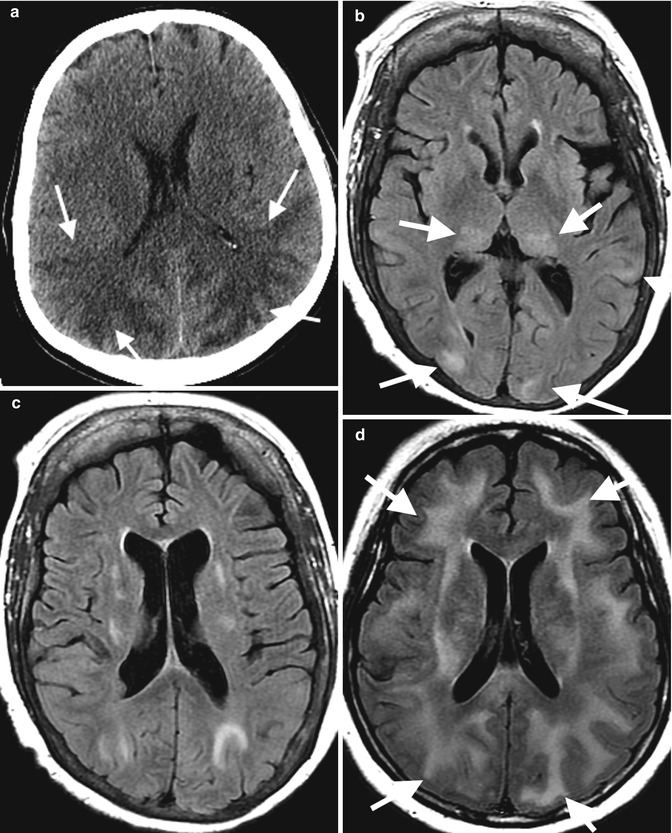

Fig. 7.6

Axial CT of a 25-year-old female with history of SLE with features of PRES on (a) axial CT with extensive posterior circulation deep white matter low attenuation and (b, c) a different patient on axial T2 FLAIR MRI with posterior circulation high signal intensity (arrows). (d) Chronic lupus cerebritis with superimposed hypertensive crisis and PRES on axial T2 FLAIR (arrows) (Kindly submitted by Dr. Judith Coret-Simon, St. Joseph’s Healthcare, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada)

About 1–2 % of patients develop transverse myelitis. This presents with a rapid onset of motor, sensory, and autonomic dysfunction. This is usually correlated with positive antinuclear antibodies and anti-double-stranded DNA. Edema and a hyperintense signal in the spinal cord are present on T2 MRI (Fig. 7.7).

Fig. 7.7

A 56-year-old female with systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with numbness of all extremities, left arm weakness, and ataxia. MRI of the cervical spine revealed a high T2 signal abnormality contiguously affecting C1–C4 segments of the cervical cord consistent with transverse myelitis (black arrows)

Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS)

MRS is a noninvasive imaging procedure that involves biochemical metabolites or neuronal markers such as N-acetylaspartate (NAA), creatine/phosphocreatine, and choline which are quantified in the brain. In the majority of NPSLE, decreased NAA is noted. However these findings are seen in degenerative brain pathologies. Reversibility after treatment would distinguish this from the latter. MRS may be utility as well in monitoring progression of NPSLE. At present, it’s more a clinical tool for research.

Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) and Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

SPECT measures cerebral perfusion using radiolabeled tracers. There has been conflicting data however about its utility. Patchy diffuse hypoperfusion is characteristic of this disease. Focal lesions are noted in patients with a longer duration of disease usually noted in the parietal and temporal lobe and occasionally in the basal ganglia. SPECT could detect abnormalities long before the development of irreversible impairment. PET measures the metabolic activity including glucose uptake and oxygen utilization. In SLE, the most frequent finding is hypometabolism in the parietal area and parieto-occipital area. PET may demonstrate widespread regional increases and decreases in brain glucose uptake. This imaging device has been advocated to be more sensitive than MRI especially with subtle changes in NPSLE. Limitations of PET include cost and the duration of the test. Further clinical studies are required to evaluate its position in the imaging algorithm in clinical practice.

CAT Scan (CT)

The role of CT remains to be unclear in NPSLE. It is usually performed in the acute presentation of neurologic deficits to exclude infarction or intracranial hemorrhage. CT however is significantly less sensitive than MRI for the assessment of white matter lesions.

Angiogram

Central nervous system vasculitis in SLE is a secondary type of vasculitis. The role of angiogram may be valuable if findings are present such as typical stenosis or occlusion “beading pattern” of the vessels. However magnetic resonance angiography has superseded formal angiograms.

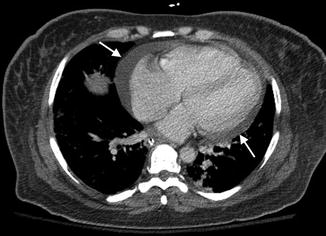

Pulmonary and Cardiovascular System

Pulmonary involvement in SLE can present in varying degrees involving the respiratory vasculature, airways, pleura, parenchyma, and surrounding including the diaphragm. Pleural effusions and pericardial effusion are common. Acute pneumonitis is an uncommon manifestation of SLE that may present with a clinical picture of dyspnea with productive cough plus or minus hemoptysis, tachypnea, and basal crepitations. Diagnostic investigation through bronchioalveolar lavage is key in ruling out infection. Pathology shows diffuse interstitial lymphocytic infiltration, bronchiolitis, hyaline membrane formation, alveolar hemorrhage, arterial thrombi, and interstitial edema. Furthermore, immune complex deposition may be found. Chest radiographs may demonstrate migratory pulmonary infiltrates, diffuse acinar infiltrates with predilection to the bases, or pleural effusions. Cavitary infiltrates and consolidation are unusual features in SLE pneumonitis. CT shows a ground glass appearance due to alveolitis and honeycombing and subpleural thickening in pulmonary fibrosis in chronic disease (Fig. 7.8). Gallium scintigraphy involves measuring damage through alveolar membrane permeability in a slope time activity curve from the dynamic lung imaging. Increase uptake may be noted.

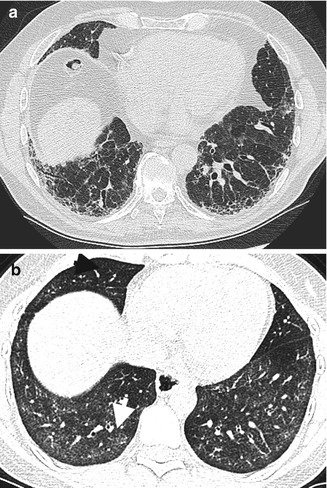

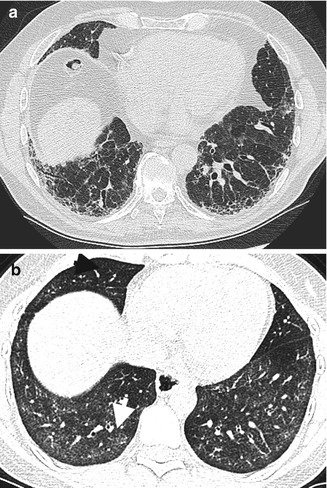

Fig. 7.8

High-resolution CT chest (HRCT) in SLE. (a) Chronic fibrosis with honeycombing, subpleural thickening, and mild ground glass attenuation of alveolitis and traction bronchiectasis. (b) Different patient with features of NSIP on this axial high-resolution image with bilateral symmetrical ground glass opacities (arrow), more pronounced at the lung bases and sparing the subpleural zones

Pulmonary hypertension involving the pulmonary vasculature can be a life-threatening complication with prevalence between 0.5 and 14 %. Its pathogenesis is thought to be related to recurrent pulmonary embolism, particularly in antiphospholipid syndrome, or chronic pulmonary fibrosis. Manifestations can be nonspecific such as dyspnea, chest pain, nonproductive cough, and jugular venous distension. Radiographic findings can initially be normal. Advanced findings can reveal enlarged central pulmonary arteries with pruning of the distal arteries and enlargement of the right ventricle on both radiographs and CT (Fig. 7.9).

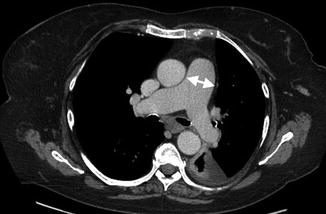

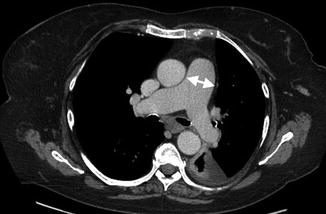

Fig. 7.9

A 52-year-old female with chronic SLE and pulmonary hypertension. Axial-enhanced CT level pulmonary artery bifurcation demonstrates enlargement pulmonary trunk with a transverse diameter of 34 mm (arrows) and small left-sided effusion

Interstitial lung disease may be in the form of nonspecific interstitial with fibrosis or organizing pneumonia. Clinical presentation may again be nonspecific with fever and a cough usually acute or insidious in onset. Plugs of fibrous tissue are noted in the respiratory bronchioles and alveolar ducts associated with inflammatory infiltrates involving the bronchioles and interstitial tissue. Although radiographic features may show evidence of interstitial lung disease, high-resolution CT better defines the different patterns. Organizing pneumonia manifests with bilateral ground glass opacities or airspace consolidation with any lung zone being affected. Bilateral airspace consolidation with lymphadenopathy or pleural effusion may also be present. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia with fibrosis presents as both ground glass appearance and irregular linear opacities, usually bibasilar (Fig. 7.8).

Pulmonary hemorrhage in SLE may present acutely with dyspnea, hypoxemia, and occasionally hemoptysis. A classic triad of hemoptysis, rapid fall in hemoglobin, and new in radiographic infiltrates is highly suspicious of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Diffusing capacity carbon monoxide (DLCO) monitoring is highly sensitive for ongoing alveolar hemorrhage. Identification of hemosiderin-laden macrophages through bronchioalveolar lavage is diagnostic. Bilateral alveolar infiltrates are noted on chest radiographs. CT allows for full assessment extent of parenchymal hemorrhage.

Neuromuscular disease and diaphragmatic dysfunction is a rare complication of SLE. The term shrinking lung syndrome has been correlated due its radiographic findings. It may cause significant morbidity and occasional mortality. The etiology is still controversial whether or not it is secondary to diaphragmatic dysfunction secondary to a myopathy, chest wall restriction, or phrenic nerve injury. It manifests as progressive dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and fever. Elevated hemidiaphragms are common in chest radiographs. Subsegmental atelectasis and ill-defined opacities above the diaphragm have also been noted. High-resolution CT scans may reveal no parenchymal involvement, elevation of the hemidiaphragms, and atelectatic bands. Pleural effusion may be present.

Cardiovascular manifestation of SLE may be either coronary or non-coronary. Non-coronary manifestation of SLE would involve the valves, endocardium, myocardium, pericardium, and sinoatrial tract causing conduction abnormalities. The prevalence of cardiovascular involvement in SLE can be as high as 50 %.

Libman–Sacks endocarditis also known as “atypical verrucous endocarditis” is the most typical valvular disease. The clinical picture is nonspecific including fever, anemia, tachycardia, and presence of the murmur in either mitral or aortic valve which are generally involved. Patients may be asymptomatic with a new murmur being the only manifestation. A hypothesis of antiphospholipid antibodies and anti endothelial antibodies binding to the endothelial cells causing platelet aggregation and thrombus formation with deposition of these immune complexes into the valvular lining is presently the known pathophysiology. The vegetations could either be active consisting of fibrin clumps and inflammatory cells or healed lesions. Transesophageal echocardiogram is more sensitive in detecting the lesions compared to transthoracic echocardiogram (50–60 % vs 40–50 %). Echocardiogram reveals thickened leaflets with or without regurgitation. Although rare, sequelae of this type of endocarditis include embolic events and chordae tendineae rupture.

Pericardial involvement in SLE is around 26 % as a common manifestation of SLE (Fig. 7.10). Patients complain of a sharp pericardial pain and dyspnea with findings of a pericardial rub, typical ECG findings, and cardiomegaly with well-defined margins on chest radiograph. Echocardiogram is the standard method utilized for diagnosing and quantitating the pericardial effusion. CT scan and MRI may also demonstrate effusion and have an advantage of providing a larger view distinguishing simple fluids from blood, assessing thickness of the pericardium and better characterization of the surrounding structures. Transudative effusions have low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, while hemorrhagic or exudative effusions have medium to high signal intensity on T1 sequences. Cardiac tamponade and constrictive pericarditis are known complications.

Myocarditis in SLE is about 7–10 % of cases likely due to initiation of immediate immunosuppressant therapy. Clinical manifestations are similar to other causes of myocarditis (i.e., infectious or toxic) and would range from resting tachycardia, overt heart failure, or conduction abnormalities. There are some reports showing an association of myocarditis and anti-SSA antibodies. Histologic findings reveal fibrinoid necrosis and infiltration on lymphocytic and plasma cells. Echocardiography is a tool used in assessing cardiac function such as segmental wall abnormalities and ejection fraction. A breakthrough in imaging is the use of cardiac MRI, which is able to detect subtle changes in the myocardium. Increase in T1 and T2 relaxation time of the myocardium is demonstrated in SLE myocarditis. An increase in T2 SI may be an indicator of active myocarditis in the absence of clinical features.

Systemic lupus erythematosus is an independent risk factor for coronary artery disease. It has been shown that the relative risk of having a myocardial infarction is 10.6 and that women between 35 and 44 have more chances of a coronary ischemic event. The basis of this phenomenon is accelerated atherosclerosis leading to a thrombotic event usually correlated with corticosteroid use and or the presence of antiphospholipid antibody. Rarely, intimal weakening can lead to aneurysmal dilatation and dissection. The gold standard for evaluating flow limiting arterial lesions is an angiogram with the most common sites involved are the left anterior descending artery and the least affected is the left main artery. Different noninvasive techniques have been proposed such as thallium scintigraphy or sestamibi which evaluates for perfusion defects, CT angiogram assessing for calcification, but moreover coronary calcium scoring has been more predictive for coronary events, and now future studies correlating these studies with SPECT would be valuable in managing these patients. Intravascular ultrasound is also used in assessing for coronary plaque features (stability) with intima–media involvement.

Gastrointestinal System

Different manifestations of gastrointestinal involvement in SLE include pseudo-obstruction, vasculitis, and thrombosis. A few may present with cholecystitis and pancreatitis. Nonspecific abdominal pain may be an initial presentation together with laboratory findings of anemia, leukocytosis, and elevated inflammatory markers. Pathogenesis is drawn from immune complex deposition and immune complex vasculopathy.

Vasculitis in the gastrointestinal tract may result in bowel ischemia, perforation, or hemorrhage. The mesenteric vessels are commonly involved with an evolved term of lupus mesenteric vasculitis (LMV). Radiographic findings may include the thumbprint sign indicating submucosal edema or hemorrhage.

Furthermore, pneumatosis intestinalis and free air can be noted. CT scan is superior to radiographic imaging in such cases revealing focal or diffuse wall thickening with abnormal enhancement known as “target sign.” Other findings include ascites and stenosis with vessel engorgement “comb sign.”

Pseudo-obstruction secondary to a SLE is a rare condition secondary to visceral smooth neuromuscular dysfunction as well as autonomic dysfunction. Pathogenesis is unknown, but a vasculitic process may play a role. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (CIPO) is a rare condition as sequelae of loss of peristaltic motility. It can be part of a triad called generalized megaviscera of lupus (GML) with components of CIPO, ureterohydronephrosis, and megacholedochus defined as hepatobiliary hollow viscera dilatation. Radiographic features reveal dilated bowel loops which are further assessed and confirmed through CT scan.

Pancreatitis in SLE has an annual incidence of 0.4–1.1/1,000 lupus patients based on the literature. This condition may be life threatening requiring immediate diagnosis and intervention. Ultrasound is usually the first line of investigation and may be normal or demonstrate a hypoechoic pancreatic gland with intra-abdominal fluid. Contrast-enhanced CT is the most useful which helps assess for severity of pancreatitis and its sequelae such as necrosis, peripancreatic collections, and secondary infected collections (Fig. 7.11). MRI would demonstrate similar findings. Acalculous cholecystitis in SLE responds well to steroid treatment. Ultrasound demonstrates gallbladder wall thickening and hyperemia without gallbladder calculi. Contrast-enhanced CT may show gallbladder wall enhancement, pericholecystic fluid attenuation, and fat stranding.

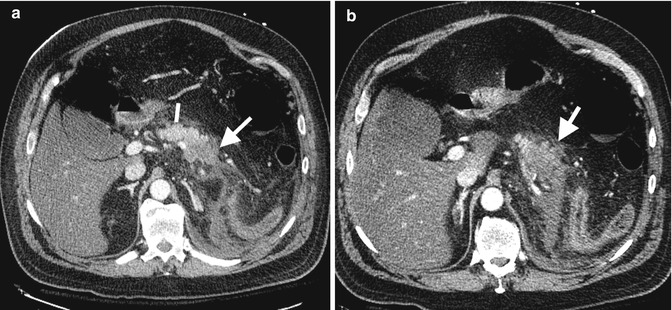

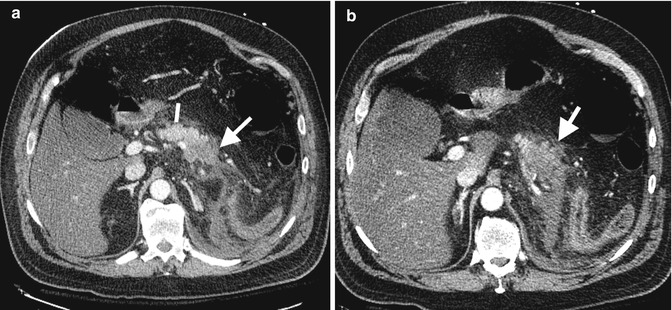

Fig. 7.11

Acute necrotic pancreatitis on axial arterial phase CT through pancreas, (a, b) note normal pancreatic enhancement proximal body (line) and diminished enhancement mid and distal body pancreas (arrows). Note also surrounding inflammatory changes

Renal System

Renal involvement is a serious complication and a major predictor of poor prognosis. Its incidence and prevalence is higher among Asian, Hispanic, and African ancestry. An immune complex microvascular injury secondary to dsDNA antibody immune complexes and imbalance of cytokine homeostasis plays an important role in its pathogenesis. Renal infarction from renal artery or vein thrombosis may be seen in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome. Renal Doppler ultrasound demonstrates compromised blood flow into the kidneys, and CT scan may reveal lack of contrast medium opacification within the thrombosed vessel and presence of collaterals in chronic cases.

Antiphospholipid Syndrome

One of the manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus is antiphospholipid syndrome. Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is defined as thrombotic and obstetrical complications associated with persistent antiphospholipid antibodies. These thrombotic complications may affect different organ systems involving arterial, venous, and microvascular structures (Fig. 7.12). Recurrent early miscarriages secondary to intraplacental thrombosis are a possible hypothesis leading to fetal loss. These criteria however lack specificity. Placenta-mediated complications are also noted in obstetrical antiphospholipid syndrome. Coagulation assays include the presence of nonspecific inhibitor or immunologic assays that include anticardiolipin antibody or anti-beta 2 glycoprotein that have to be positive in two occasions 12 weeks apart.

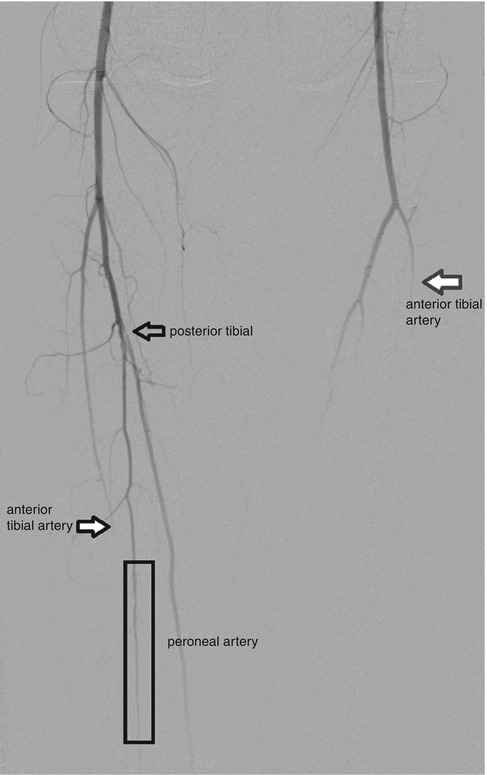

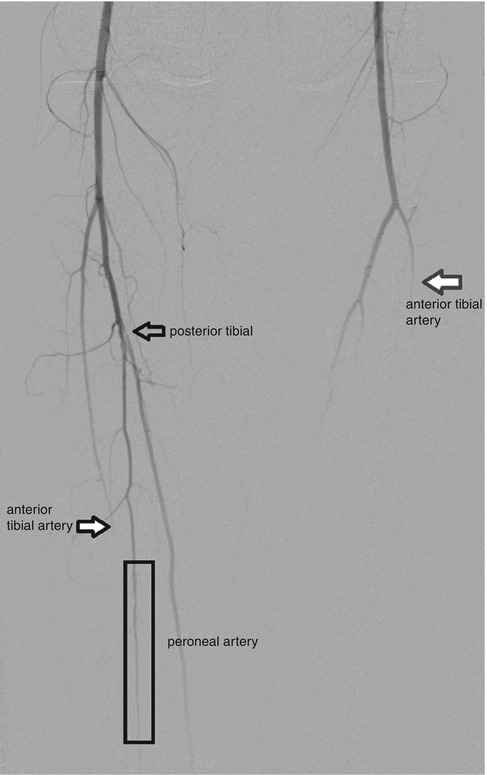

Fig. 7.12

A 36-year-old female with antiphospholipid syndrome presenting with a second left ischemic toe and right foot ulcer. Aortogram with runoffs reveals an intraluminal filling defect from the origin of the right posterior tibial artery consistent with an intravascular thrombus (outlined black arrow). Within the mid distal thirds of the right calf, the peroneal artery shows a small caliber with subtle corkscrewing (within black rectangle). Furthermore, right anterior tibial artery shows an abrupt occlusion in the mid-calf area (black arrow with white fill). The left anterior tibia abruptly occludes within the mid third of the calf (red arrow)

Clinical manifestations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus may vary from stroke-like syndromes, pulmonary embolisms (Fig. 7.13), or deep venous thrombosis and as mentioned obstetrical complications as defined above. Imaging routinely used are CT angiograms showing the occluded segment. Treatment includes lifelong anticoagulation.

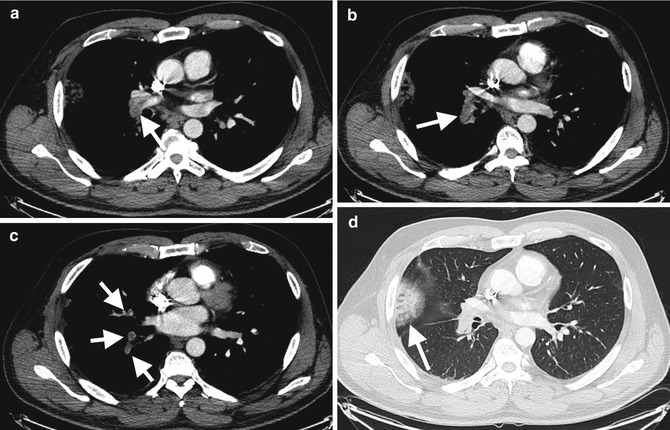

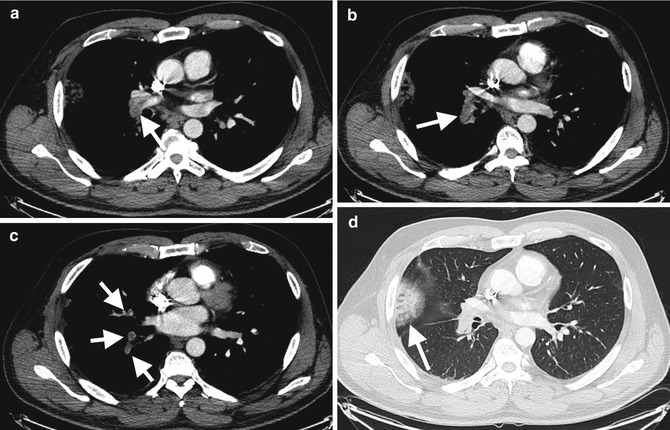

Fig. 7.13

Acute pulmonary embolism in a 28-year-old female with antiphospholipid syndrome. (a, b, c) Axial arterial phase-enhanced CT with acute filling defects (arrows) distal right pulmonary artery, right interlobar artery segmental branches, respectively, and (d) peripheral parenchymal infarct on lung windows

Mixed Connective Tissue Disease (MCTD)

Mixed connective tissue disease has been defined based on its features of four overlapping disease entities including systemic lupus erythematosus, polymyositis/dermatomyositis, scleroderma, or rheumatoid arthritis plus the presence of a high U1 RNP titer. Mixed connective tissue disease being a distinct disease entity is still controversial. It may involve both children and adults with predominance in women and prevalent in the third decade of life. The most common symptoms on disease onset is Raynaud’s 93 % and swollen hands 74 %. Interestingly, through time sclerodactyly replaces the edema phase in the hands. Joint involvement may be similar to that of rheumatoid arthritis with the presence of erosions on imaging. Other clinical features include hypomotility of the esophagus, pulmonary involvement, pleuritis or pericarditis, pulmonary hypertension in 20–30 % of patients, and proximal muscle weakness due to myositis. Radiographic findings of pulmonary involvement are similar to that of systemic sclerosis or polymyositis/dermatomyositis showing an interstitial pattern with peripheral and basal involvement. Furthermore, CT scan findings reveal ground glass opacities or honeycombing with disease progression. Serologic features besides the presence of the RNP antibody may include leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, elevated creatine kinase, and positive anti-dsDNA, anti-SM, anti-SCL-70, anti-citrullinated peptide, and anti-SSA antibodies. Treatment is usually symptom based and may require immunosuppressants.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree