Organizing pneumonia (OP) is a histologic pattern characterized by the presence of intraluminal granulation tissue polyps within alveolar ducts and surrounding alveoli associated with chronic inflammation of the surrounding lung parenchyma. Because the granulation tissue polyps frequently also involve the bronchioles, the pattern was previously known as bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP). However, given the confusion of this entity with bronchiolitis obliterans (synonym: obliterative or constrictive bronchiolitis), this terminology has fallen out of favor. OP may occur in association with several underlying conditions, including infections, connective tissue diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, inhalational injury, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, drug reaction, radiation therapy, and aspiration. In some patients, no underlying cause is found, however, and the condition is termed cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) ( Box 29.1 ).

- •

Idiopathic (cryptogenic organizing pneumonia)

- •

Connective tissue disease

- •

Drug reaction

- •

Infection (including bacteria, Mycoplasma, fungi, and Pneumocystis )

- •

Human immunodeficiency virus related

- •

Aspiration

- •

Hemorrhage

- •

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- •

Malignancy (solid tumor and hematologic)

- •

Posttransplantation (particularly stem cell transplantation)

- •

Postradiation

- •

Inhalational injury (toxic fume or smoke inhalation)

- •

Vasculitis syndromes (particularly granulomatosis with polyangiitis and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis [Churg-Strauss syndrome])

- •

Inflammatory bowel disease

- •

Nonspecific reaction adjacent to other lesions (e.g., infarct, abscess, and neoplasm)

- •

Cocaine abuse

- •

Anthrax vaccination (rare)

Etiology, Prevalence, and Epidemiology

COP accounts for 4% to 12% of cases of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. The exact incidence and prevalence of COP is not known as many cases are undiagnosed, and cases described in the literature are often based on presumptive diagnosis. Although COP and secondary OP are thought to occur at similar rates, the cause for secondary OP is often difficult to identify or not exhaustively sought after. A population-based epidemiologic review of OP in Iceland estimated that the mean annual incidence of OP was 1.97 per 100,000 population, including 1.10 cases of COP and 0.87 cases of secondary OP per 100,000 population, respectively. COP has an equal sex distribution and is approximately twice as common in nonsmokers than in smokers. The average age of presentation is 50 to 60 years (range, 20–80 years). Occasionally, COP may have seasonal recurrence. In one study the authors reported 12 patients with seasonal recurrence of COP for 3 to 11 years. In all 12 patients symptoms recurred between late February and early May every year, tending to increase in severity each year. One case has been reported of recurrent COP starting 2 to 3 days before the menstrual period and resolving within 5 to 10 days.

Clinical Presentation

Patients usually present with cough and progressive dyspnea of relatively short duration (median, <3 months). The cough may be dry or productive of clear sputum. Other common manifestations include weight loss, chills, and intermittent fever. The clinical presentation mimics that of community-acquired pneumonia. Auscultation usually reveals localized or widespread crackles. Finger clubbing is absent.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

OP is characterized histologically by the presence of intraluminal plugs of granulation tissue within alveolar ducts and surrounding alveoli ( Fig. 29.1 ), with or without concomitant granulation tissue polyps within the respiratory bronchioles ( Fig. 29.2 ). The distribution is typically patchy, and the connective tissue is of the same age. Mild associated interstitial inflammation is typically present with type II cell metaplasia and an increase in alveolar macrophages. Even though the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society consensus statement classifies COP as a form of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, the abnormalities are mainly intraalveolar.

Lung Function

Pulmonary function tests usually show a mild to moderate restrictive ventilatory pattern with decrease in total lung capacity and vital capacity and impairment in gas exchange with decrease in carbon monoxide diffusing capacity. The patients frequently are hypoxemic.

Manifestations of the Disease

Radiography

The most common radiographic manifestation of OP consists of bilateral symmetric or asymmetric areas of consolidation ( Figs. 29.3 and 29.4 ). The consolidation usually has a patchy distribution but may involve mainly the subpleural regions. Occasionally, the areas of consolidation may be migratory, decreasing in size in one area and appearing in previously unaffected regions. An unusual case of levitating consolidation has been described; the bilateral areas of consolidation migrated cephalad during a period of months and gradually disappeared after reaching the lung apices.

The size of individual areas of consolidation ranges from about 1 cm to almost an entire lobe. Their margins are indistinct, and they may contain air bronchograms. The lung volume may appear preserved or decreased. Occasionally, the areas of consolidation may be round, resulting in multiple large nodular opacities or masses. A pattern of small nodular, reticular, or reticulonodular opacities may be seen in association with airspace opacities or occasionally as an isolated finding. Small unilateral or bilateral pleural effusions are seen in about 20% of patients.

Computed Tomography

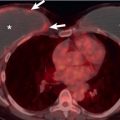

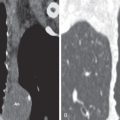

The characteristic high-resolution computed tomography (CT) manifestation of OP consists of patchy areas of consolidation. The consolidation is usually bilateral and most commonly involves mainly the middle and lower lung zones. In 60% to 80% of cases the consolidation has a predominantly peribronchial or subpleural distribution ( Figs. 29.5 to 29.7 ). The areas of consolidation may decrease in size in one area and appear in previously unaffected regions ( Fig. 29.8 ).

Another characteristic feature of OP is a perilobular pattern, seen in approximately 60% of patients ( Fig. 29.9 ). A perilobular pattern is defined as linear opacities that are of greater thickness and are less sharply defined than opacities encountered in thickened interlobular septa and that have an arcade-like or polygonal appearance. The perilobular pattern frequently abuts the pleural surface and is surrounded by aerated lung parenchyma. The perilobular pattern results from accumulation of organizing exudate in the perilobular alveoli, with or without interlobular septal thickening at histologic examination. Less commonly, OP may result in crescentic or ring-shaped opacities surrounding areas of ground-glass opacification. These have been referred to as the atoll sign or as the reversed halo sign. The reversed halo sign is seen in approximately 20% of patients with OP ( Figs. 29.10 and 29.11 ). Histopathologically, the central areas of ground-glass opacification were shown to correspond to alveolar septal inflammation, whereas the ring-shaped or crescentic periphery corresponds mainly to OP within alveolar ducts. The atoll sign or reversed halo sign is not pathognomonic for OP and may be seen in pneumonias (classically mucormycosis and tuberculosis), granulomatosis with polyangiitis, pulmonary infarcts, and sarcoidosis; however, in the subacute to chronic setting, it is usually diagnostic of OP.