Introduction

Cystic lung diseases present a considerable diagnostic challenge mainly because CT findings can be similar in many of these diseases. In addition, a number of pulmonary abnormalities can result in cystic patterns that mimic true lung cysts. However, the combination of characteristic imaging findings, clinical features, and genetic testing, where appropriate, often permits an accurate diagnosis. In this chapter, we review the unique CT features of individual cystic lung diseases and provide a systematic approach to a confident radiologic diagnosis.

Spectrum and Prevalence of Cystic Lung Disease

Diffuse cystic lung diseases are rare entities. The most well-known diffuse cystic lung diseases are lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) and pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH). The estimated incidence of LAM is from 1 to 2.6 cases/1,000,000 women, although the true incidence is likely higher because LAM is often mistakenly diagnosed for asthma, bronchitis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLCH is also uncommon. In a clinical series of 502 patients, the diagnosis of PLCH was made in about 3.4% of individuals undergoing open lung biopsy for chronic diffuse infiltrative lung disease. However, the exact prevalence of PLCH is unknown because a significant number of affected patients may be asymptomatic, and the disorder may undergo spontaneous resolution.

Owing to the recent more widespread use of CT, differential diagnosis of these rare entities becomes more extensive than previously described, including Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (BHD), lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP), light chain deposition disease (LCDD), and amyloidosis. Infectious processes including Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PJP) and human papillomavirus–associated papillomatosis have also been described to result in cyst formation.

Diffuse cystic lung diseases may be categorized on the basis of CT appearance, clinical history, and serologic evaluation. Many diffuse and focal or multifocal cystic lung diseases demonstrate bronchiolocentric distribution of cysts, as well as abnormal cellular infiltration on histopathology ( Table 24.1 ). Based on their CT appearance, the diseases can be organized based on whether the cysts are sparse or numerous in number and whether there are associated findings, such as nodules or ground-glass opacities. A history of systemic diseases and prior infection is often helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis ( Table 24.2 ).

| CYSTIC LUNG DISEASE | BRONCHIOLOCENTRIC LESION |

|---|---|

| Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH) | Mixed inflammatory nodule (CD1a-positive Langerhans cells, lymphocytes, macrophages) close to bronchioles |

| Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) | Spindle cell proliferation in distal airways |

| Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis (LIP) | Lymphocytic cell proliferation along airways |

| Desquamative interstitial pneumonitis and respiratory bronchiolitis–interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD) | Pigment-laden macrophages in respiratory bronchioles and alveolar ducts |

| Amyloid–light chain deposition disease (LCDD) | Peribronchial lymphoplasmacytoid infiltrates and light chain deposition |

| SYSTEMIC DISEASE | PATHOLOGY | HIGH-RESOLUTION CT FINDINGS |

|---|---|---|

Primary systemic amyloidosis

| Amyloid light chain

|

|

Kappa light chain deposition disease

|

|

|

Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis

| Lymphocyte proliferation along airways |

|

Demographics, Genetics, and Role of Other Causative Factors

Knowledge about the patient’s demographics, family history, medical history, and environmental exposure, particularly a history of cigarette smoking, is often helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis.

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

LAM is almost exclusively a disease of women. Although previously characterized as a disease of women of childbearing age, there has been increasing detection of subclinical disease in postmenopausal women. LAM occurs in two forms, sporadic and in association with tuberous sclerosis complex. The sporadic form accounts for 85% of cases and is generally associated with more severe pulmonary cystic changes. Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal dominant disease, but 60% of tuberous sclerosis patients have no family history of the disease, and the disease is the result of a new germline mutation. Mutations in the tumor suppressor genes TSC1 and TSC2 are associated with the development of LAM. Less than one-third of tuberous sclerosis patients have the classic triad of seizures, adenoma sebaceum, and mental retardation.

Pulmonary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis and Desquamative Interstitial Pneumonia

PLCH is a disease of smokers, occurring most frequently in young adults with a current or past smoking history. Smoking prevalence has ranged from 80% to 100% in various studies. The diagnosis of PLCH can therefore be confidently excluded in a nonsmoker. Although PLCH was previously reported as more common in men, there is no longer a gender predilection due to increased smoking in women.

Cyst formation has also been described in desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP), a smoking-related interstitial lung disease. DIP is a rare disease entity almost exclusively seen in individuals exposed to cigarette smoke. It is characterized by macrophage accumulation within the alveoli. Patients may have dyspnea or cough. Confirmation of the smoking history is mandatory before suggesting a diagnosis of DIP on radiologic grounds.

Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome

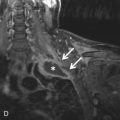

BHD is an autosomal dominant disease caused by a mutation in the BHD gene, which encodes for the tumor suppressor protein folliculin. Most patients with pulmonary cysts will have facial fibrofolliculomas distributed over the face, neck, and upper trunk. Renal tumors such as oncocytomas and renal cell carcinomas may be seen and are frequently multifocal and bilateral. Hence, identification of subpleural cysts in association with facial fibrofolliculomas should prompt further genetic testing and MRI evaluation of the abdomen to screen for renal neoplasms.

Lymphocytic Interstitial Pneumonia

LIP is a rare entity and may be idiopathic or may be seen more commonly in patients with an underlying immunologic abnormality. In particular, LIP has been associated with Sjögren syndrome, AIDS, primary biliary cirrhosis, Castleman disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and autoimmune thyroid disease. LIP is more common in women, likely due to the association of LIP with autoimmune disease. It is currently controversial whether LIP represents a benign lymphoproliferative disorder or a form of early lymphoma, and mediastinal and hilar lymph node enlargement is sometimes seen in these patients.

Light Chain Deposition Disease

LCDD occurs in middle-aged patients, with 75% of cases occurring in association with multiple myeloma or macroglobulinemia. LCDD usually involves the kidneys. Although lung involvement is rare, LCDD can result in respiratory failure, necessitating lung transplantation.

Amyloidosis

Pulmonary cysts are rare manifestations of amyloidosis and are usually described with localized amyloidosis in association with Sjögren syndrome. A cystic lung pattern is rarely seen in systemic amyloidosis associated with multiple myeloma, macroglobulinemia, rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, or Crohn disease.

Appropriate Imaging Modalities for the Evaluation of Patients With Cystic Lung Disease

CT is used as a diagnostic study, usually after a standard chest radiograph is obtained or when the chest radiograph result is considered to be abnormal. CT should be performed during deep inspiration at total lung capacity. High-resolution CT (HRCT) using thinner sections of 1 to 1.25 mm is recommended to evaluate the fine details of the pulmonary parenchyma. Contrast material may not be required for routine assessment of cystic lung disease unless there is a concomitant concern for mediastinal, vascular, or pleural abnormalities.

Importance of Ancillary Extrathoracic Findings

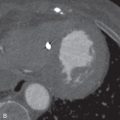

Identification of ancillary extrathoracic findings (e.g., renal tumors, skin findings) helps narrow the differential diagnosis and can alert the clinician to the possibility of underlying familial syndrome. Specifically, both tuberous sclerosis and BHD are associated with renal neoplasms.

The most common renal tumor in tuberous sclerosis complex is an angiomyolipoma, which is more common in patients with a TSC2 gene mutation. The incidence of renal cell carcinoma in tuberous sclerosis is similar to that in the general population but the tumors occur at a younger age, typically in the third decade of life, as compared to the more usual presentation in the fifth decade. Thoracic and/or abdominal chylous effusion is also characteristic of tuberous sclerosis complex. All patients newly diagnosed with LAM should have imaging of the abdomen and pelvis. Annual brain MRI is recommended for all patients with tuberous sclerosis until 21 years of age and then every 2 or 3 years to diagnose and monitor subependymal giant cell astrocytomas.

Imaging of the abdomen and pelvis should also be performed in patients newly diagnosed with BHD. In BHD, renal tumors are often multiple, may be bilateral, and are noted at an earlier age (mean, 50.7 years) than the general population. The tumors include chromophobe oncocytoma, renal cell carcinoma, and clear cell carcinoma.

Pitfalls: How to Differentiate True Cystic Lung Disease From Mimics

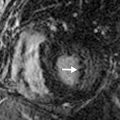

On HRCT, the term lung cysts refers to a thin-walled (usually <2 mm), well-circumscribed, and well-defined air-containing lesion that is 1 cm or larger in diameter. The mechanism of cyst development is unclear, but in some cases appears to be related to small airway obstruction. Several other pulmonary abnormalities feature a cystic pattern that mimics true cystic lung disease, but do not manifest true lung cysts. These include honeycombing, bronchiectasis, emphysema, and cavitary nodules ( Fig. 24.1 ).

Honeycombing can be differentiated from true cysts because of their thicker walls; they are lined by fibrous tissue. The subpleural location—stacked appearance of cysts—in honeycombing and the presence of other signs of fibrosis also help distinguish honeycombing from true cysts. Bronchiectasis represents dilation and distortion of the airways and hence typically maintains tubular structure or orientation. Coronal and sagittal reformations are helpful in delineating communication with the bronchial tree. Emphysematous bullae and centrilobular emphysema are focal areas of permanent destruction of the bronchiolar walls, with resultant enlargement of the air space distal to the terminal bronchiole. By definition, bullae are 1 cm or more in diameter and have imperceptible walls that are less than 1 mm thick. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish bullae from true lung cysts, although the central location of the vascular structures and other signs of extensive emphysema frequently allow correct diagnosis. Cavitary nodules have much thicker and more irregular walls than true lung cysts.

Problem Solving and Case Scenarios

Diseases Associated With Numerous Cysts (Diffuse Cystic Lung Disease)

Diseases associated with numerous cysts are easy to diagnose due to important differentiating features. The differential diagnosis is short and includes LAM and PLCH; these two disease entities can be differentiated based on demographics, clinical features, and history of smoking, as well as characteristic imaging findings.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with numerous cysts frequently present with abnormal pulmonary function test results, airflow obstruction, and low diffusing capacity, given the significant underlying cystic abnormality. The clinical presentation may sometimes be sudden, with acute shortness of breath due to spontaneous pneumothorax from rupture of cysts. Although LAM is considered to be a disease of young women, PLCH is frequently encountered in smokers and is more common in men.

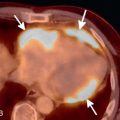

Chest Radiographic and CT Findings

Radiographic abnormalities include increased lung volumes, hyperinflation, linear interstitial opacities, and cystlike lucencies ( Fig. 24.2A ). Patients with PLCH may also demonstrate a reticulonodular abnormality involving the upper and mid zones of the lungs.