and Gustavo Marino2

(1)

Attending Physician VA Medical Center, George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

(2)

Chief Gastroenterology Section VA Medical Center, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

4.1.1 Anatomy

4.1.2 EUS Probes

4.1.3 Technique

4.2.1 Duodenal Cancer

4.2.2 Duodenal Diverticulum

4.2.4 Duodenal Pseudocyst

4.2.5 Ampullary Carcinoma

4.2.7 Periduodenal Collaterals

Abstract

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) examination of the duodenal wall reveals a five-layer sonographic pattern similar to that of the esophagus, stomach, and rectum, thickness varies depending on the tension applied. The bile duct and pancreatic duct converge at the major papilla, which usually appears as a small hypoechoic structure.

4.1 General Principles

4.1.1 Anatomy

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) examination of the duodenal wall reveals a five-layer sonographic pattern similar to that of the esophagus, stomach, and rectum, as described in Chaps. 2, 3, and 8, respectively. Wall thickness varies depending on the tension applied. The bile duct and pancreatic duct converge at the major papilla, which usually appears as a small hypoechoic structure.

4.1.2 EUS Probes

High-frequency probes, including miniprobes (catheter EUS probes) advanced through the standard endoscope channel, have the advantage of higher resolution. However, these high-frequency probes provide limited depth of sonographic visualization. Evaluation of deep involvement, adjacent anatomical structures, and lymph nodes is better with dedicated EUS radial and linear scanning endoscopes.

4.1.3 Technique

Endoscopic ultrasound examination of focal small lesions can be targeted after initial endoscopic visualization while a systematic insertion and withdrawal technique allows for the identification of anatomic landmarks such as the major papilla and larger lesions. An appropriate ultrasound wave conduction interface is necessary; this can be accomplished by suctioning all luminal air and direct contact of the endoscope with or without a water-filled balloon or with water infusion filling the lumen. Focal distance can be adjusted by processors to improve the resolution, according to the depth of the area of interest. Endosonographers have variable preferences but should be able to combine these techniques, depending on the location of the lesion. Compression and tangential scanning of the wall should be minimized to avoid false interpretation of the findings.

Box 4.1: Resources

American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines: The role of endoscopy in ampullary and duodenal adenomas http://www.asge.org/assets/0/71542/71544/8f8a3952917f4fe78f3855ff0ec77d07.pdf

Familial adenomatous polypopsis: APC-Associated Polyposis Conditions (Review)

Jasperson KW, Burt RW. APC-Associated Polyposis Conditions. 1998 Dec 18 (Updated 2011 Oct 27). In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al., editors. GeneReviews™ [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1345/

Surgical management of neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract

Lyen C. Huang, MD, MPH, George A. Poultsides, MD, Jeffrey A. Norton, MD Aug 15, 2011. CancerNetwork.com: http://www.cancernetwork.com/gastrointestinal-cancer/content/article/10165/192182

DAVE Project – Gastroenterology: Duodenum, carcinoid tumor With EUS FNA

DAVE Project – Gastroenterology: Duodenum, adenoma treated with argon plasma coagulation in a patient with FAP

DAVE Project – Gastroenterology: Duodenum, malignant mass evaluated by EUS

4.2 Cases and Discussions

4.2.1 Duodenal Cancer

This is a 66-year-old man who was evaluated for anemia by upper endoscopy and colonoscopy. The colonoscopy was unremarkable but, based on the results of the endoscopic biopsies, the upper endoscopy showed what appeared to be a benign villous adenoma in the third portion of the duodenum. The patient was referred for EUS evaluation, and this study showed a superficial tumor that did not involve the muscularis propria. However, there was one 1.7-cm-diameter lymph-node-like structure immediately adjacent to the involved area. EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the lymph node revealed adenocarcinoma.

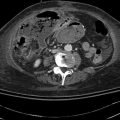

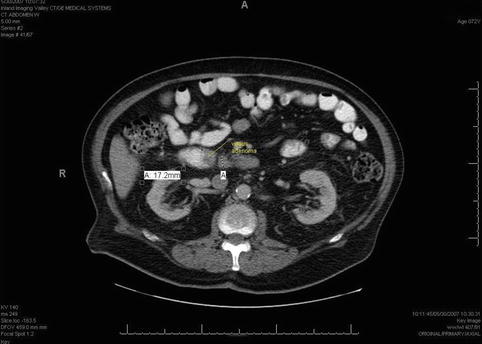

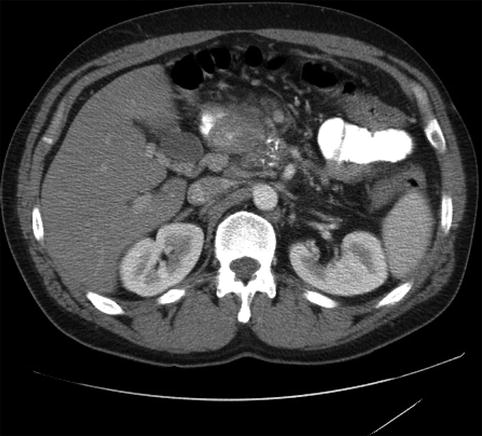

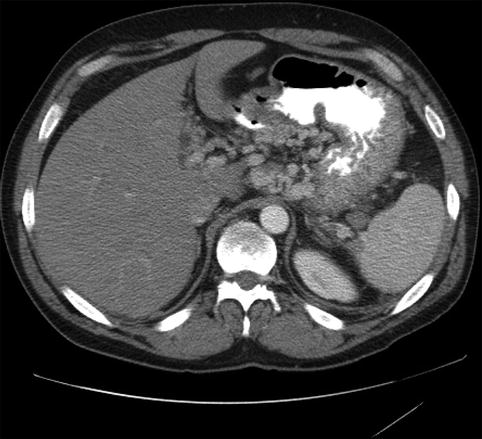

Fig. 4.1

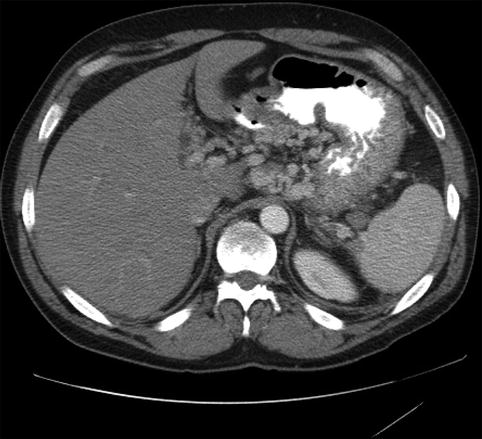

This computed tomography scan shows a duodenal mass with an adjacent lymph node (retrospectively identified as such following the endoscopic ultrasound)

Fig. 4.2

This is the villous-appearing lesion in the duodenum. Endoscopic surface biopsies showed only villous adenoma, and the lesion appears to be confined to the mucosa/submucosa

Fig. 4.3

In addition to the villous lesion in the duodenal lumen, a hypoechoic adjacent lymph-node-like structure can be seen

Fig. 4.4

This radial endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) image shows a close-up of the periduodenal lymph node. EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration revealed adenocarcinoma

In this case the presence of metastatic lymphadenopathy proven by EUS allowed the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma and indicated the need for surgery. An article from UCLA Medical Center summarizing 40 years of experience with this rare tumor reported that prognosis of duodenal cancers was related more to tumor size, local invasion, and histologic grade than tumor spread to local lymph nodes and that the disease can be potentially curable by surgery even with local lymph node involvement [1]. However, more recent articles have found that metastatic lymph node involvement decreases the rate of survival. A study from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center showed that survival at 5 years was 83 % in patients without nodal invasion and was 56 % in those with positive nodes [2]. A recent publication from Johns Hopkins reported that 5-year survival was 68 % in patients without lymphadenopathy versus 58 % in those with 1–3 positive nodes and 17 % in patients with ≥4 positive nodes [3]. In summary, lymph node involvement is again considered a significant prognostic factor, and EUS/FNA has the ability to provide this information.

4.2.2 Duodenal Diverticulum

Duodenal diverticula can be mistaken for cystic pancreatic abnormalities on cross-sectional imaging, especially when they are not filled with air or contrast but fluid [4]. These are two patients in whom periampullary duodenal diverticula and the absence of pancreatic cystic lesions were nicely demonstrated during EUS.

Fig. 4.5

This is a water-filled periampullary duodenal diverticulum that mimicked a hypodense lesion on a computed tomography scan of the pancreas

Fig. 4.6

This is another periampullary diverticulum (div), which contains debris

Fig. 4.7

This image reveals the connection to the duodenal lumen. (div) diverticulum

Duodenal diverticula are common in the periampullary area. The presence of these diverticula can limit the evaluation of the distal common bile duct (CBD) or periampullary region on standard imaging studies. Diverticula can contain debris, and they usually fill with air during standard endoscopy. Careful endoscopic visualization of this area is important to avoid false EUS interpretations, particularly if scanning from the duodenal bulb. In these cases filling the diverticulum with water provides appropriate ultrasound wave transmission and allows for a reliable interpretation of adjacent structures.

4.2.3 Duodenal Perforation by Foreign Body

A 65-year-old woman presented with abdominal pain, weight loss, and fever. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen showed a retroperitoneal abscess. A duodenal perforation was suspected. The initial upper endoscopy was reportedly unremarkable. The patient was referred for EUS evaluation. Surface endoscopy during EUS showed a duodenal microperforation. EUS showed an echogenic shadowing structure (not air) directly behind the perforation site. Since nothing was seen on the CT scan in this location, a toothpick or a fish bone were the prime suspects. The patient was treated with percutaneous drainage and long-term antibiotics. Eight weeks after the initial presentation she developed portal vein thrombosis, probably related to the presence of the abscess.

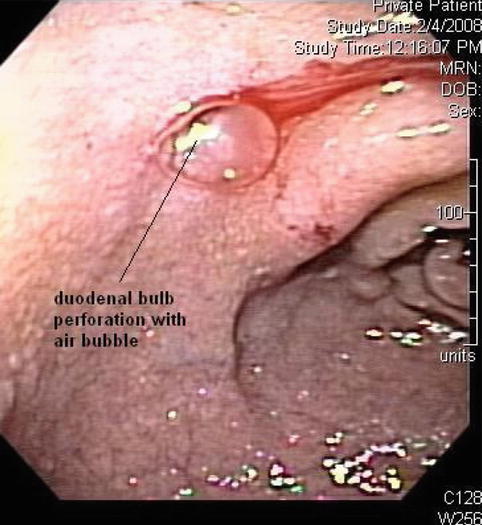

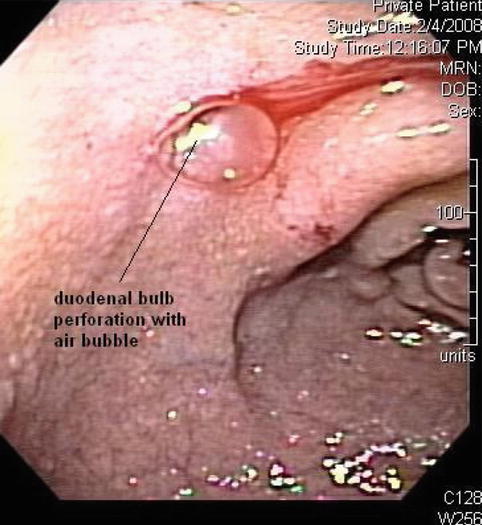

Fig. 4.8

A small 3- to 4-mm-diameter perforation is visible in the duodenal bulb on this esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Fig. 4.9

Endoscopic ultrasound shows an echogenic round shadowing structure immediately adjacent to the perforation site

Fig. 4.10

The nature of this foreign body is unclear. A broken-off tooth pick or a fish bone are considerations

Fig. 4.11

The portal vein appeared normal at initial presentation

Fig. 4.12

The abscess was managed with percutaneous drainage and antibiotics. This endoscopic ultrasound 8 weeks later shows a portal vein thrombosis adjacent to the abscess

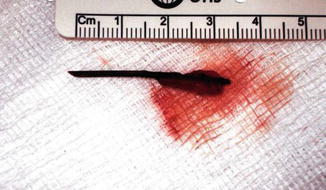

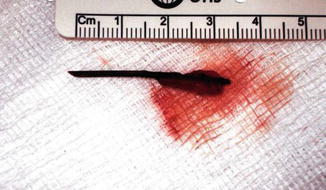

Fig. 4.13

This endoscopic ultrasound shows venous collaterals bypassing the completely clotted portal vein

Fig. 4.14

A toothpick after laparoscopic extraction from a different patient (From Al-Khyatt et al. [5])

Metallic objects (except aluminum), most animal bones, and all glass foreign bodies are opaque on radiographs. Most plastic and wooden foreign bodies and most fish bones are not opaque on radiographs. These can be missed occasionally by CT scan [6], as shown in this case. Ultrasound techniques are helpful in the detection of wooden foreign bodies as small as 2.5 mm long, as shown in multiple reports [7–9].

A systematic review of injuries related to toothpick ingestion reported between 1966 and 2000 [10] found that most patients (70 %) present with abdominal pain, and most commonly reported complications include perforation, bleeding, peritonitis, abscess, or obstruction. However, only a minority (12 %) of patients remembered swallowing a toothpick. The most common site of injury is the duodenum (25 %), although this can occur throughout the entire gastrointestinal tract, and the toothpicks can migrate to the pleura, pericardium, peritoneum, ureter, or bladder. Major vessel involvement can also occur. Therefore, it is important to define the exact location of the entire toothpick before attempting endoscopic removal, which is contraindicated in patients with peritonitis or vessel penetration [11].

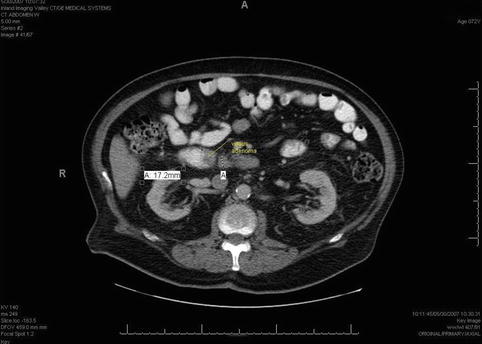

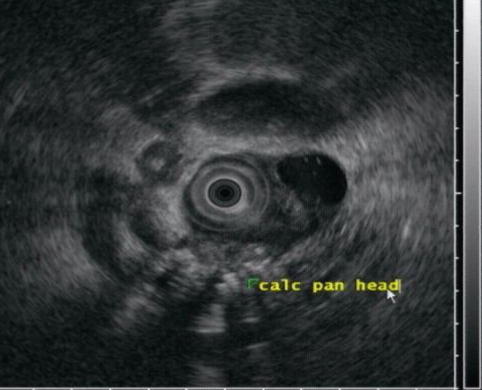

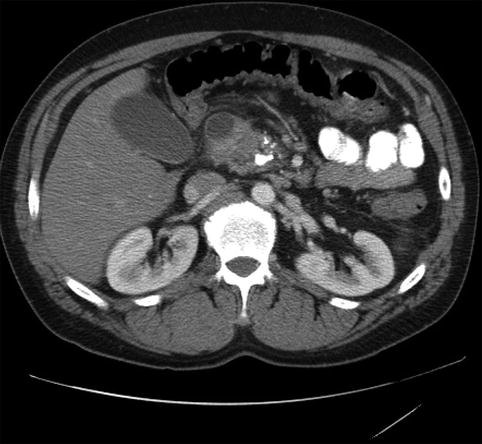

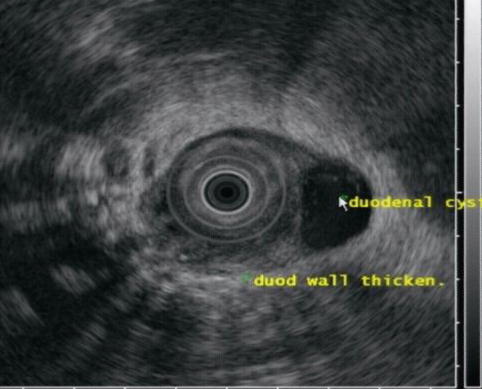

4.2.4 Duodenal Pseudocyst

This is a 42-year-old man with a drug and alcohol problem who was admitted to the hospital with intractable abdominal pain and because a CT scan had shown a paraduodenal mass. An EUS was requested for further evaluation of multiple abnormalities seen on CT. The EUS showed that there was actually a smaller cyst within the duodenal wall and another larger one, characteristic of a pseudocyst, adjacent to it. The small cyst, if it had been isolated, would have probably been called a duplication cyst. However, the clinical context and the fact that it had resolved 6 months later make it much more likely that this is a duodenal wall intramural pseudocyst.

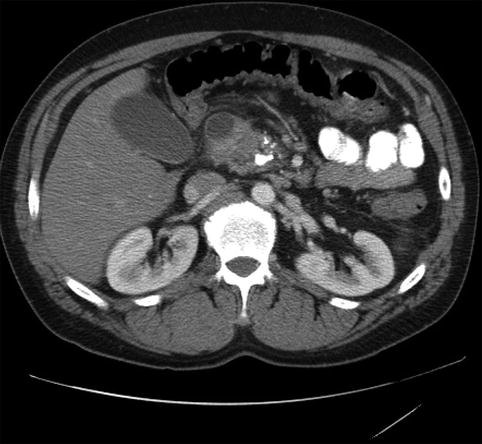

Fig. 4.15

A duodenal cyst on a computed tomography scan of the abdomen

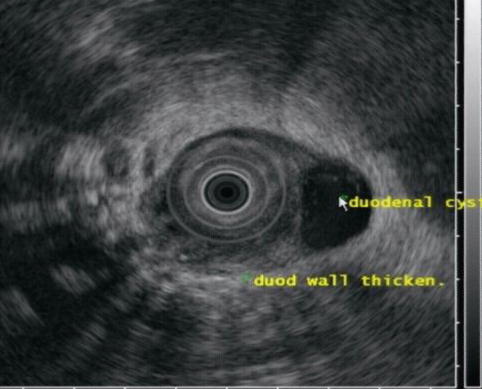

Fig. 4.16

The same duodenal cyst as seen on endoscopic ultrasound

Fig. 4.17

Extensive collateral circulation on computed tomography secondary to splenic vein thrombosis

Fig. 4.18

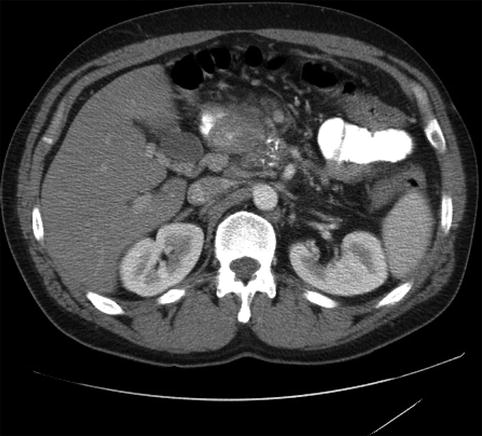

A periduodenal mass as seen on computed tomography

Fig. 4.19

The periduodenal mass is shown to be a septated pseudocyst on this endoscopic ultrasound

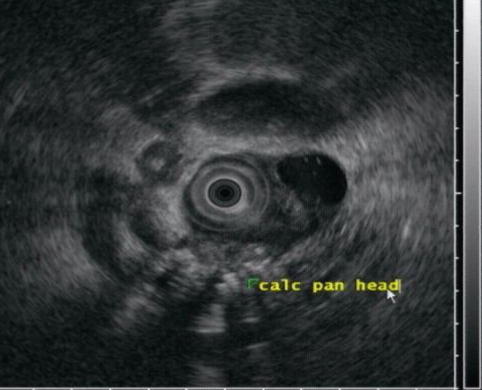

Fig. 4.20

Changes of severe chronic pancreatitis with calcifications are seen

Pseudocysts that migrate into the wall of the duodenum or elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract, including the stomach and colon, have been reported [12], but awareness of this phenomenon is limited in the medical community. Duodenal pseudocysts are found between the muscularis propria and the mucosa or between serosa and muscularis propria. The surface of the posterior wall of the duodenum is in direct contact with the head of the pancreas, without a clear barrier to the disruptive effect of pancreatitis and pseudocysts. Complications of these lesions include perforation or duodenal obstruction. EUS allows for the detection of these cystic-appearing lesions, which can be confirmed by aspiration of fluid rich in amylase [13].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree