Fig. 1.1

Schematic illustration of the embryologic development of the pancreas. (a) At about 4 weeks of gestation, the primitive pancreas is formed by a dorsal pancreatic and ventral pancreatic bud that arises from the endodermal lining of the duodenum. (b) At 6 weeks, the ventral bud and the bile duct rotate clockwise behind the duodenum (curved arrow). (c) The ventral pancreatic bud lays posteroinferior to the dorsal pancreatic bud. (d) By about 7 weeks, upon reaching its final destination, the dorsal pancreatic bud fuses with the ventral pancreatic bud to form the final pancreas

It starts during the fourth week of gestation.

The pancreas originates from the endodermal lining of the duodenum.

Two outpouchings develop at the junction of the foregut and midgut:

One ventral bud (caudal)

One dorsal bud (cranial)

The ventral pancreatic bud forms the posterior part of the head and the uncinate process.

The dorsal pancreatic bud forms the anterior part of the head, body, and tail of the pancreas.

The main pancreatic duct (Wirsung) is formed from the ventral duct and the distal portion of the dorsal duct.

The accessory duct (Santorini) may be present due to the persistence of the proximal portion of the dorsal pancreatic duct.

At the sixth week of gestation, as the foregut elongates, the ventral pancreas, gallbladder, and bile duct rotate clockwise posterior to the duodenum and join the dorsal pancreas.

At the seventh week of gestation, the ventral pancreatic bud fuses with the dorsal bud, forming a single pancreas.

The ventral pancreatic duct and the common bile duct (CBD) are linked by the embryonic origins, which results in the adult configuration of the common entrance into the duodenum at the major papilla.

1.3 Congenital Disorders of the Pancreas

Congenital anomalies of the pancreas and pancreatic duct may be clinically insignificant and may create a diagnostic dilemma.

These congenital anomalies may not be detected until adulthood by computed tomography or magnetic resonance as incidental findings in asymptomatic patients.

1.3.1 Agenesis of the Pancreas

1.3.1.1 Classification

Complete absence of the ventral and dorsal pancreas

Complete absence of the dorsal pancreas

Hypoplasia of the dorsal pancreas

1.3.1.2 Complete Agenesis of the Ventral and Dorsal Pancreas

Extremely rare.

Lethal condition.

Can be associated with other malformations (gallbladder aplasia, polysplenia, fetal growth retardation, heterotaxy syndrome, and intestinal malrotation).

This congenital anomaly has been linked with mutation in the GATAG, PDX1, and PTF1A genes.

1.3.1.3 Agenesis of the Dorsal Pancreas (Fig. 1.2)

Fig. 1.2

Agenesis of the dorsal pancreas. Illustration shows the posterior portion of the head and the absence of the dorsal pancreas

Rare anomaly.

Results from a failure of the dorsal pancreatic bud to form the anterior head, neck, body, and tail of the pancreas.

Etiology of this congenital abnormality is currently not well understood.

Can be associated with intrauterine growth retardation, heterotaxy syndrome, and intestinal malrotation.

Clinical presentation

Most patients are asymptomatic.

Patients with this anomaly may present with nonspecific abdominal pain, diabetes mellitus, steatorrhea, or jaundice.

Imaging findings (Figs. 1.3 and 1.4)

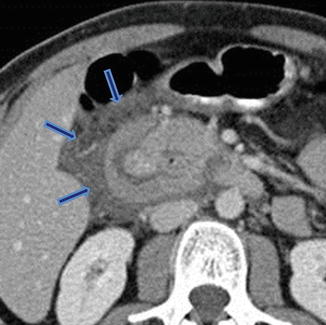

Fig. 1.3

Agenesis of the dorsal pancreas on computed tomography (CT). (a, b) Axial view of a contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen reveals a normal head (arrows) of the pancreas and the absence of the body and tail. Note the presence of mild dilatation of the distal common bile duct (arrowhead)

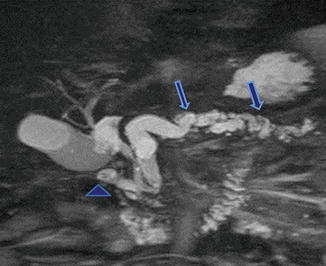

Fig. 1.4

Agenesis of the dorsal pancreas on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A 27-year-old female with heterotaxia. (a, b) Axial and coronal T1-weighted images with fat suppression show a prominent head of the pancreas (arrows) associated with absence of the body and tail of the pancreas. Note the abnormal position of the stomach (S)

Absence of the anterior head, neck, body, and tail of the pancreas

Short, rounded, posterior pancreatic head

1.3.1.4 Hypoplasia of the Dorsal Pancreas (Figs. 1.5–1.7)

Fig. 1.5

Hypoplasia of the dorsal pancreas. Illustration shows the absence of the tail of the pancreas

Absence of the distal body and tail of the pancreas

Clinical presentation

Usually an incidental finding by cross-sectional imaging.

Most patients are asymptomatic.

Imaging findings

Fig. 1.6

Hypoplasia of the dorsal pancreas on contrast-enhanced CT (CECT). (a, b) Axial view and (c) coronal view show the absence of the distal body and tail of the pancreas (arrows). Note the truncated appearance of the distal pancreas (curved arrows)

Fig. 1.7

Hypoplasia of the dorsal pancreas on CT. (a, b) 3D volume-rendered coronal images show a truncated distal pancreas (arrows)

Truncated pancreatic body and absence of the tail of the pancreas

Normal pancreatic head, neck, and proximal body

Differential diagnosis

Atrophy of the dorsal pancreas related to a pancreatic neoplasm located in the head/neck of the pancreas

Atrophy of the distal pancreas secondary to chronic pancreatitis

1.3.2 Pancreatic Divisum (Fig. 1.8)

Fig. 1.8

Illustration of pancreatic divisum. This diagram demonstrates the dorsal (arrows) and ventral ducts (arrowheads) draining separately

Most common congenital anomaly of the pancreas.

It has been reported in 4–10 % of the population.

This abnormality results from failure of the dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds to fuse during the sixth to 8 weeks of gestation.

The pancreatic head and uncinate process are drained by the duct of Wirsung through the major papilla.

The body and tail of the pancreas are drained by the duct of Santorini through the minor papilla.

Clinical presentation

Most patients with pancreatic divisum are asymptomatic.

This anomaly can be associated with recurrent episodes of pancreatitis.

It is postulated that in pancreatic divisum, the duct of Santorini, and the minor papilla are too small to adequately drain the pancreatic secretions produced by the pancreatic body and tail.

Practical Pearl

In young patients with repetitive attacks of pancreatitis and no obvious risk for this condition, the possibility of pancreatic divisum should be considered high on the list of the differential diagnoses.

Imaging

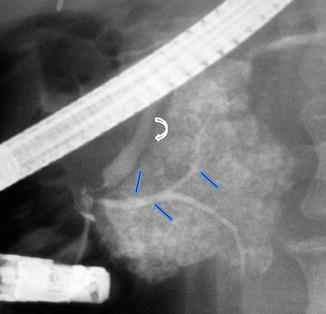

Fig. 1.9

Pancreatic divisum on ERCP. Fluoroscopic film obtained after contrast injection into the main pancreatic duct shows opacification and distal abrupt cutoff of the ventral duct (arrows) associated with acinarization. The common bile duct is also identified (curved arrow)

Fig. 1.10

Pancreatic divisum on CECT. (a) Coronal and (b) axial views of a CECT of the abdomen with 3D volume-rendering reformatted images reveal a prominent duct of Santorini (arrows) running parallel to the duct of Wirsung (arrowheads) and absence of connection between these ducts

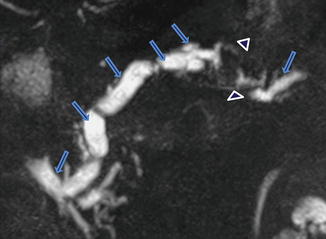

Fig. 1.11

Pancreatic divisum on MRCP. (a) Coronal and (b) axial thick slab views of an MRCP show a prominent dorsal duct draining through the minor papilla (arrows) and a smaller ventral duct draining through the major papilla (arrowheads)

Fig. 1.12

Pancreatic divisum associated with pancreatitis. A nine-year-old male patient with recurrent history of pancreatitis. (a) Axial views of a single shot fast spin echo T2 weighted image of the abdomen and (b) coronal thick slab from an MRCP show a prominent dorsal duct draining into the minor papilla (arrows). Note the irregularity and narrowing of the dorsal duct proximal to this papilla. The ventral pancreatic duct was not identified. In addition, note the presence of a pancreatic pseudocyst in the pancreatic head (arrowheads)

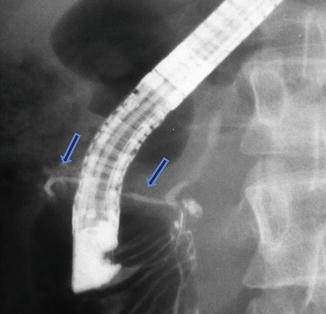

Fig. 1.13

Pancreatic divisum associated with chronic pancreatitis. A forty-five-year-old female with history of chronic epigastric pain and steatorrhea. Coronal view of MRCP thick slab demonstrates a beaded dilated dorsal duct (arrows). The ventral duct appears slightly prominent and does not communicate with the dorsal duct. There is an area of signal void in the distal body of the pancreas (arrowheads) that corresponds with pancreatic calcifications noted on a previous CT

Best imaging modalities: endoscopic cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP).

ERCP used to be the only effective imaging modality to establish this diagnosis.

ERCP findings: (Fig. 1.9)

(a)

Ventral duct: appears short and tapered after cannulating and injecting contrast material into the major papilla; this duct does not cross the midline.

(b)

Acinarization in the head (after attempting to fill the remainder of the duct).

Practical Pearl

The identification by ERCP of a short truncated ventral duct in an adult patient may be seen related with malignancy; consequently, correlation with other imaging modalities is recommended.

MRCP has replaced ERCP to establish the diagnosis of pancreatic divisum.

This technique is noninvasive and rapid and does not require the use of contrast material.

Avoids risks of ERCP-induced pancreatitis.

MRCP/CECT findings (Figs. 1.10–1.13)

Dorsal pancreatic duct in direct continuity with the duct of Santorini; this duct drains into the minor papilla.

A short ventral duct which does not communicate with the dorsal duct; this ventral duct joins with the distal bile duct to enter the major papilla.

The head of the pancreas may have an elongated appearance.

The administration of secretin improves the sensitivity of MRCP.

Differential diagnosis

Conditions associated with obstruction of the distal pancreatic duct

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Neuroendocrine tumor

Chronic pancreatitis

Annular pancreas

Trauma with pancreatic neck fracture

Treatment

Asymptomatic patient

No specific treatment

Symptomatic patient

Surgical sphincteroplasty at the minor papilla or endoscopic dilatation of the minor papilla and stent placement

Practical Pearl

Endoscopic manipulation of the minor papilla has a risk to induce severe acute pancreatitis.

1.3.3 Annular Pancreas(Figs. 1.14 and 1.15)

Fig. 1.14

Annular pancreas. Illustration shows a ring of pancreatic tissue encircling the second portion of the duodenum

It is a rare congenital anomaly in which incomplete rotation of the ventral bud leads to a band of the pancreas encircling the duodenum.

Location

Second portion of the duodenum (85 %)

First or third portions of the duodenum (15 %)

Classification

Complete band (25 %)

Incomplete band (75 %)

Epidemiology of this congenital anomaly is unclear (many cases are undetected since annular pancreas is not always associated with symptoms).

There are three main hypotheses to explain this anomaly

Adhesion of the right ventral bud to the duodenal wall

Persistence of the left ventral bud

Tip of the ventral bud adhering to the duodenum, with the duodenal rotation resulting in a ring of pancreatic tissue

Associated congenital abnormalities (75 %):

Esophageal atresia

Imperforate anus

Congenital heart disease

Malrotation of the midgut

Down syndrome

Clinical presentation

50 % of the patients develop gastrointestinal or biliary obstruction during the first year of life.

50 % of the adult patients may be asymptomatic for life and it may be discovered incidentally.

When symptomatic, the presentation is usually in the third to sixth decade of life.

This anomaly may be associated with gastric outlet obstruction, peptic ulcers, gastrointestinal bleeding, acute or chronic pancreatitis, or biliary obstruction.

Patients may complain of abdominal pain, postprandial fullness, vomiting, or jaundice.

Imaging Findings

Fig. 1.15

Annular pancreas gross appearance. Annular pancreas found incidentally in a patient that underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy for a small ampullary carcinoma. (a–c) Photographs of the gross specimen show a band of pancreatic tissue completely encircling the second portion of the duodenum (arrows)

Fig. 1.16

Annular pancreas on plain abdominal films. (a, b) Flat abdominal films from two neonates with intractable vomiting demonstrating distention of the stomach (S), as well as distention of the first portion of the duodenum (D) “double bubble” sign

Fig. 1.17

Annular pancreas on barium upper gastrointestinal series (UGI). (a, b) Anterior views of the duodenum demonstrate a concentric narrowing of the second portion of the duodenum (arrows). Note the normal duodenal mucosa at this level (Courtesy of Claudio Cortes, MD)

Fig. 1.18

Annular pancreas on barium upper gastrointestinal series (UGI) and computed tomography. (a) UGI examination shows an eccentric narrowing in the second portion of the duodenum (arrows). (b) Contrast-enhanced CT shows a rim of pancreatic tissue (arrows) surrounding the contrast-filled duodenum

Fig. 1.19

Annular pancreas on contrast-enhanced CT. (a) Axial, (b) coronal, and (c–d) oblique 3D volume-rendered reconstructions demonstrate a band of pancreatic tissue (arrows) completely encircling the second portion of the duodenum associated with luminal narrowing (arrowheads)

Fig. 1.20

Annular pancreas associated with acute pancreatitis. Axial view from an abdominal CECT shows the second portion of the duodenum encircled by a band of pancreatic tissue. Note the inflammatory changes around the duodenum in this region (arrows) (Courtesy of Sandor Joffe, MD and Elina Zaretzky, MD)

Fig. 1.21

Annular pancreas on magnetic resonance. (a) Axial view on T1-weighted image reveals a band of pancreatic tissue surrounding the second portion of the duodenum (arrow). (b, c) Single shot fast spin echo T2-weighted axial image and coronal MRCP thick slab anterior and posterior views (c, d) demonstrate a pancreatic duct encircling the duodenum (arrows)

Fig. 1.22

Annular pancreas associated with chronic pancreatitis. A 62-year-old male with history of chronic epigastric pain. MRCP thick slab demonstrates a pancreatic duct encircling the duodenum (arrowhead). Note the dilatation and beaded appearance of the main pancreatic duct (arrows)

Fig. 1.23

Annular pancreas on ERCP. Fluoroscopic image after the injection of contrast into the main pancreatic duct demonstrates a small duct originating from the main pancreatic duct and partially encircling the second portion of the duodenum (arrows)

Plain abdominal films (Fig. 1.16)

“Double bubble” sign

Large proximal bubble: dilated stomach

Small distal bubble: dilated duodenal bulb

Differential diagnosis

Duodenal atresia, intestinal malrotation (neonates)

Duodenal tumor, pancreatic tumor invading the duodenum (adults)

Upper gastrointestinal examination(Figs. 1.17 and 1.18)

Extrinsic narrowing of the second portion of the duodenum

Distention of the proximal duodenum and stomach

Differential Diagnosis

Duodenal carcinoma

Pancreatic carcinoma

Postbulbar ulcer

Computed Tomography(Figs. 1.19 and 1.20)

Normal pancreatic tissue with or without a small pancreatic duct encircling the second portion of the duodenum.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree