Fig. 9.1

A 50-year-old male with CRF on long-term hemodialysis with right ankle swelling secondary to amyloid arthropathy. (a) AP, (b) mortise view, and (c) lateral radiographs demonstrate well-defined erosions in the tibia, fibula, and talus with well-defined sclerotic margins (arrowheads) and joint distension (arrow)

Radiographic findings of large joint amyloid arthropathy resemble inflammatory arthritis including juxta-articular soft tissue swelling, mild periarticular osteoporosis, and subchondral cystic lesions, usually with well-defined sclerotic margins. The joint space is preserved until late in the course of the disease. Distribution is frequently bilateral. Osseous amyloidomas are well-defined lucent lesions of the medullary cavity or are subcortical with scalloping. Patients may present with a pathologic fracture.

MRI (Fig. 9.2)

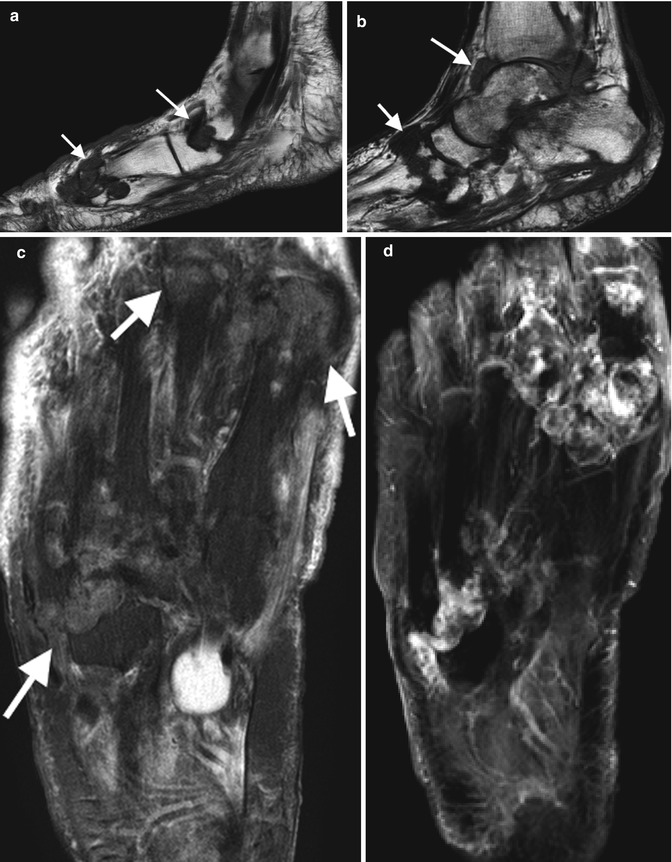

Fig. 9.2

A 60-year-old male on long-term hemodialysis with bilateral swelling in the feet and pain, MRI demonstrates features in keeping with amyloid arthropathy, (a, b) Sag TI foot with multifocal well-defined erosions (arrows) with sclerotic margins at intertarsal and tarsometatarsal joints and ankle joint distension, (c) axial T2FS with intermediate to low SI tissue (arrows) at involved joints, and (d) axial T1FS PG demonstrating heterogeneous enhancement of intra-articular soft tissue at sites of erosions

MRI can identify amyloid deposition in the muscle and bone. The MR imaging appearance of amyloid infiltration within or around the joint consists of extensive deposition of an abnormal soft tissue that has low or intermediate signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images. This abnormal material covers the synovial membrane, fills subchondral defects, and extends to the periarticular soft tissue. Joint effusion is usually present.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is a simple and useful tool in confirming joint effusions and synovial proliferation. Inhomogeneous hypoechoic synovial thickening without increased flow on Doppler is typically seen within the joint or bursa. Similar ultrasound appearance can be found in the soft tissue, e.g., infiltrating around the median nerve with intratendinous and peritendinous involvement in carpal tunnel syndrome.

Nuclear Medicine

Nuclear medicine has a limited role in the assessment of MSK involvement in amyloidosis. Scintigraphy with radiolabeled serum amyloid P component is a specific investigation that can provide a map of amyloid deposition in tissues.

CT

CT has a limited role in the assessment of MSK involvement in amyloidosis particularly with the availability of MRI.

Acromegaly

Overview

Acromegaly is a rare disorder secondary to hypersecretion of the growth hormone from the pituitary gland, usually secondary to a pituitary adenoma. Presentation will differ between children with unfused growth plates and adults. In the former, there is excessive growth of bone leading to gigantism. In older children with fused growth plates and adults, there is also bone overgrowth but more so in width with related overgrowth of soft tissue and is termed acromegaly. Diagnosis is often delayed as symptoms and clinical features develop slowly.

Musculoskeletal Presentation

There is coarsening of the facial features with an enlarged protruding jaw (prognathism) and forehead (frontal bossing), poor dental occlusion, enlargement of the tongue, and coarse skin. The hands are enlarged and often described as spade-like with soft tissue enlargement of the tufts, increased number of sesamoid bones, and exostoses at tufts with similar changes occurring in the feet. In addition, there is increased heel fat pad thickness, >25 mm. Common musculoskeletal presentations include arthralgia, osteoarthritis, CPPD arthropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, and back pain.

Imaging Features (Figs. 9.3 and 9.4)

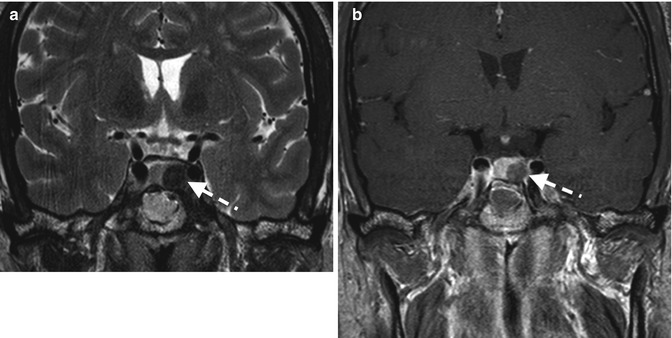

Fig. 9.3

MRI sella in patient with acromegaly demonstrating a left-sided pituitary adenoma (dashed arrows), (a) Cor T2 demonstrates low SI adenoma and (b) Cor T1 PG normal enhancing pituitary with limited enhancement of the adenoma

Fig. 9.4

PA radiograph in patient with acromegaly, note thickening of soft tissue (dashed arrow), widened joint spaces (arrowhead), and prominent ungual tufts (arrow). The metacarpals and phalanges are thickened with early osteophytes at the MCPJs (Kindly submitted by Dr. Gina Di Primio, University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada)

There are characteristic features of the acromegaly. Radiographs of the hands demonstrate joint space widening due to cartilage overgrowth. The cartilage however is not as durable as normal cartilage and predisposes to early degenerative osteoarthritis. The short bones of the hand are widened particularly the bases of the distal phalanges. There are small bone outgrowths at the site of ligament and tendon attachments. In addition, there is widening of the tufts with small exostoses and overlying soft tissue thickening. The sesamoid at the first Metacarpophalangeal joint (MCPJ) is enlarged and has been used as a radiographic feature of acromegaly via the sesamoid index. Changes on foot radiographs are similar to those described for the hands.

A lateral skull radiograph may demonstrate prognathism, overgrowth of the paranasal sinuses that, via the frontal sinuses, contributes to frontal bossing. The pituitary fossa may be enlarged and there may be thickening of the skull vault. Spinal radiographs demonstrate enlargement of vertebrae in AP and lateral dimensions, prominent end plate osteophytosis, and posterior vertebral scalloping. The intervertebral disk is enlarged. There is increased thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis.

Alkaptonuria

This is a rare autosomal recessive metabolic disorder related to the absence of an enzyme, homogentisic acid oxidase, with subsequent accumulation of homogentisic acid (HA) in the body. HA is deposited in various organs and induces a bluish-black discoloration of tissues including the cartilage of the ear (ochronosis). HA is excreted in the urine, which turns dark if left to stand. Musculoskeletal presentation, secondary to HA deposition in cartilage and connective tissue, includes arthralgia and back pain from large joint and intervertebral disk involvement. The intervertebral disks demonstrate calcification, disk degeneration, and vacuum phenomenon. The outer fibers of the annulus fibrosus may ossify and simulate syndesmophytes. The vertebrae are osteoporotic. Degenerative changes are common at the sacroiliac joints, symphysis pubis, and large joints. Degenerative changes in large joints may be atypical, e.g., involving just one compartment of a multicompartmental joint or involve a joint not exposed to primary osteoarthritis such as the glenohumeral joint. Tendinous calcification may occur.

Wilson’s Disease

Wilson’s disease, also known as hepatolenticular degeneration, is a rare autosomal recessive metabolic disorder with excessive accumulation of copper in tissues and subsequent organ dysfunction. Features are most prevalent in the liver (cirrhosis), the brain and basal ganglia (movement disorders including ataxia and parkinsonism, psychiatric disorders), kidneys (renal tubular acidosis), and the cornea (Kayser-Fleischer rings). Ceruloplasmin is usually low. Musculoskeletal involvement includes a CPPD-like arthropathy, chondrocalcinosis, subchondral bone fragmentation, and degenerative changes particularly in large joints, osteopenia, and osteomalacia.

Hemochromatosis

Overview

Hemochromatosis, primary and secondary, is a disease of abnormal iron metabolism causing chronic iron overload and iron deposition in parenchymal organs. Primary hemochromatosis is a common autosomal recessive genetic disorder, which is caused by a defect in the HFE gene, the protein product of which regulates iron absorption from the gastrointestinal tract. Of two known important mutations in HFE, C282Y and H63D, C282Y is the most important and accounts for more than 95 % of symptomatic cases of hemochromatosis. Primary hemochromatosis affects 1:200 persons of Northern European decent with the highest prevalence being in people of Celtic origin. Although the genetic defect is distributed equally among men and women, the iron loss as a result of menstruation is protective, resulting in a clinical male predilection (M: F ~ 2–10:1). In men, the diagnosis usually becomes evident in middle age (30–40 years of age), whereas in women, clinical manifestation is delayed until the postmenopausal period.

Typical organs involved are the joints, liver, heart, pancreas, pituitary, nerves, and skin. The most common manifestation is hyperpigmented skin (“bronze” skin) and hepatomegaly. Arthralgia is present in up to 50 % of patients. Diabetes, heart failure, arrhythmia, hypothyroidism, hypogonadism, and hypopituitarism are other well-recognized clinical manifestations of hemochromatosis.

Secondary iron overload is rare but can be due to frequent blood transfusions, hemolytic anemia, myelodysplasia, juvenile hemochromatosis, and Friedreich’s ataxia.

Musculoskeletal Presentation

Hemochromatosis can affect most joints in the body, but the primary articular manifestation of the disease is a characteristic symmetric, noninflammatory arthritis affecting the second and third MCPJs. Given this joint distribution, hemochromatosis may mimic rheumatoid arthritis. Absence of inflammatory features (increased warmth and erythema) helps to differentiate it from rheumatoid arthritis. Patients with hemochromatosis may also have recurrent attacks of pseudogout secondary to calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD) (see chap. 8). Hemochromatosis arthropathy has an insidious onset and may occur at any stage during the course of the disease; in rare cases, it is the initial manifestation. Over time, large joints such as the hips, knees, and shoulders can be affected. The pathogenesis of hemochromatosis arthropathy has been associated with the presence of iron in joint tissue, a defect in cartilage metabolism, and immunological dysfunction. It is usually a slowly progressive non-deforming disease.

Imaging Features

Radiographs (Fig. 9.5)

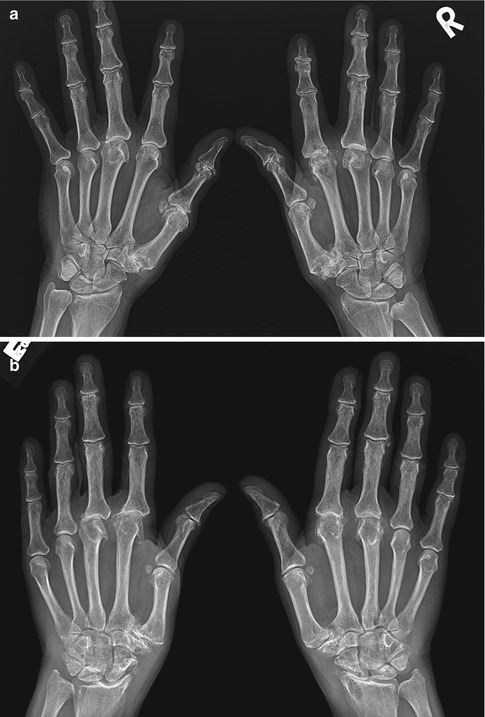

Fig. 9.5

(a) A 62-year-old female with hemochromatosis, AP radiography of the bilateral hands demonstrates degenerative changes at the MCPJs, most pronounced at the second and third and the first CMC joints, subtle chondrocalcinosis of the left TFC. (b) AP radiograph bilateral hands with more advanced degenerative changes and hooklike osteophytes of the MCPJs in a 48-year-old male with hemochromatosis, also radiocarpal degeneration with scalloping radius and subchondral cyst formation, typically seen in CPPD arthropathy. (c) The same patient, AP knee radiograph with chondrocalcinosis and large medial tibiofemoral osteophytosis. (d) CT abdomen with secondary cirrhosis, liver is atrophic with surface nodularity (dashed arrow)

Radiographs are the mainstay of musculoskeletal imaging in hemochromatosis and occasionally may provide the first suggestion of the disease. Hemochromatosis arthropathy presents with features of degenerative joint disease on plain radiograph. Hemochromatosis causes destruction of joint cartilage due to defect in cartilage metabolism, and patients present with features of a secondary osteoarthritis. Radiographs demonstrate joint space narrowing, sclerosis, and osteophytosis with associated diffuse osteoporosis. However, in hemochromatosis, radiographs show degenerative changes with some unusual features. These include involvement at the joints that are not commonly involved in degenerative joint disease, such as the MCPJs, wrists, elbows, and glenohumeral articulations. Hooklike osteophytes on the radial aspect of the metacarpal heads of the second and third MCPJs are characteristic.

Furthermore it may be characterized by global joint space narrowing and chondrocalcinosis, an unusual finding in degenerative joint disease. Arthropathy may be associated with multiple cysts in the subchondral bone, which can occasionally reach a large size. The joint space loss is associated with subchondral bony eburnation and cyst formation. Periarticular erosions and deformities are not features of hemochromatosis. Subchondral radiolucency of the femoral head and atypical stripping of the cartilage from the subchondral bone are thought to be specific radiographic and histological changes of hemochromatosis arthritis.

MRI/CT/US/Nuclear Medicine

These modalities are usually not required in the assessment of hemochromatosis-related arthropathy. Occasionally MRI or ultrasound can be used for assessment of active synovitis.

Hemophilia

Overview

Hemophilia is a rare inherited bleeding disorder. Hemophilia A (factor VIII deficiency) affects less than 1 in 10,000 people. Hemophilia B (factor IX deficiency) is even less common, affecting approximately 1 in 50,000 people. The most severe forms of hemophilia almost always affect males due to X-linked inheritance pattern. Females can be seriously affected only if the father is a hemophiliac and the mother is a carrier or in the case of X-inactivation that occurs at an early stage of embryogenesis resulting in unusually low levels of factor VIII or IX. These cases are extremely rare. The degree of factor VIII deficiency correlates with the extent of bleeding, and hemophilia A can be classified as severe (<1 % activity), moderate (1–5 %), or mild (5–25 %). Common symptoms of hemophilia are surface bruising, hematuria, and peritoneal, retroperitoneal, and intracranial bleeding as well as MSK involvement.

Musculoskeletal Presentation

Musculoskeletal involvement includes soft tissue muscle hemorrhage, hemarthrosis, and intraosseous hemorrhage. The most commonly affected joints are the large joints, i.e., knees, elbows, ankles, hips, and shoulders. In patients with severe form of hemophilia, spontaneous bleeding occurs with minimal or no trauma. Joint involvement in severe forms of hemophiliac patients occurs in up to 90 % of patients by the age of 10 years. Recurrent intra-articular bleeding resulting in arthropathy is a leading cause of morbidity in hemophilia.

Hemophilic arthropathy is a joint-destroying disorder that is more prevalent before adulthood. Hemorrhage begins in the synovium before extending into the joint space. Blood causes an inflammatory response in the synovium, resulting in synovial hypertrophy and joint hyperemia. These responses make further bleeding more likely. Intra-articular bleeding is associated with joint effusion that can persist for days without treatment. Recurrent intra-articular hemorrhages cause hemosiderin deposition. Periarticular osteoporosis and regional soft tissue swelling are commonly seen with repeated bleeding. Initially the joint space is preserved. As arthropathy progresses, symmetric cartilage destruction and joint space narrowing are observed. Later manifestations of hemophilic arthropathy include osseous irregularity and erosions with secondary severe degenerative joint disease, including osteophytes, large subchondral cysts, and sclerosis. Subchondral cystic changes are thought to be due to both synovial intrusions through fissures in the joint surface and primary intraosseous hemorrhage. Eventually joint ankylosis may occur.

Imaging Features

Radiographs (Figs. 9.6 and 9.7)

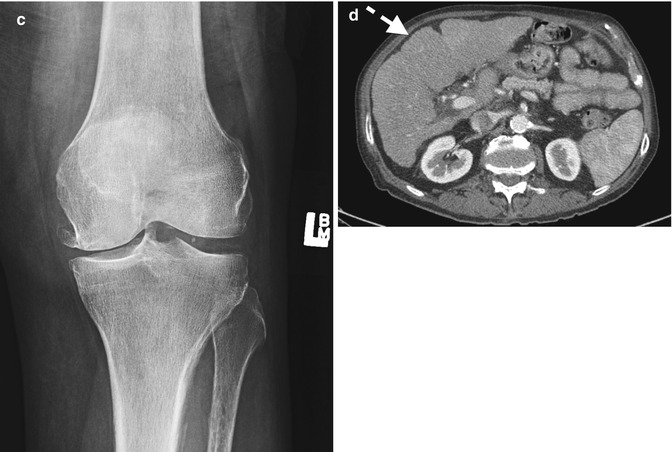

Fig. 9.6

(a) AP and (b) lateral radiographs of the elbow in a 25-year-old male with secondary degenerative changes secondary to recurrent hemarthrosis. (c) A 37-year-old-male hemophiliac with recurrent hemarthrosis (dashed arrows) at the knee joint with prior arthroplasty for secondary degenerative disease

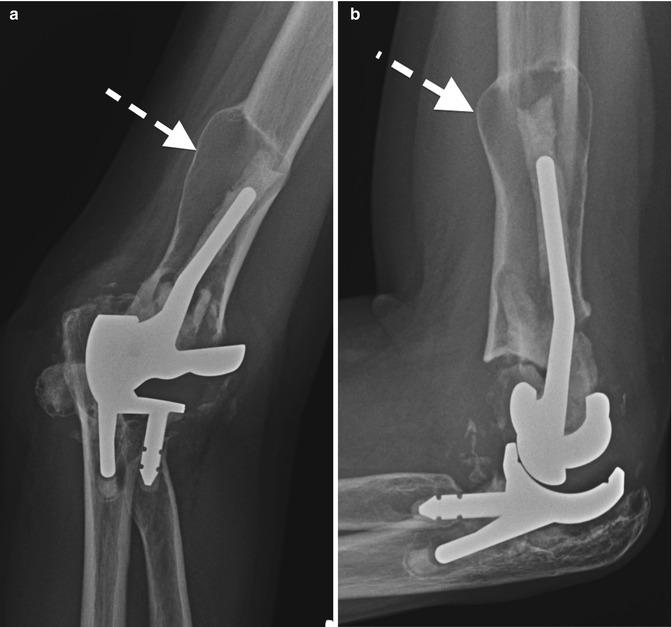

Fig. 9.7

(a) AP and (b) lateral radiographs of the left elbow in a hemophiliac with prior arthroplasty demonstrating pseudotumor appearance with secondary loosening prosthesis. Note intramedullary lucency and expansion with cortical thinning of the distal humerus (dashed arrows)

Plain radiography is the primary imaging tool for evaluation of hemophilic joint disease. Radiographic features depend on the stage of the disorder. In the initial hemarthrosis, the radiographic finding is similar to a joint effusion. Increased density within the joint may reflect synovial hypertrophy and/or hemosiderin deposition following repeated hemorrhages. Later radiographic findings include extensive erosive and degenerative joint changes as described above with osteopenia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree