Fig. 1

Transvaginal sonography showing an ovarian endometrioma (*) along with a sigmoid colon with thickened bowel wall and hyperechoic submucosal layer (#) in a Crohn’s disease patient

2 Etiology and Pathogenesis

Several hypotheses have been advanced to explain the ectopic location of endometrial tissue (Oral and Arici 1997). The most common explanation is the retrograde passage of endometrial tissue, which then implants on pelvic organs and peritoneum. From these sites, more distant localizations may arise via hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination; further dissemination may occur during surgical interventions. A less accepted hypothesis is that of endometrial metaplasia, an alteration caused by the metaplastic transformation of multipotential peritoneal mesothelial cells in endometrial tissue.

Endometrial tissue is regulated by hormonal influence: estrogen promotes and progesterone inhibits growth. These repetitive cycles of growth and sloughing of ectopic tissue can lead to serosal irritation and progressive invasion of bowel muscle with fibrosis and muscular hypertrophy. This may lead to bowel strictures or intestinal kinking with the risk of developing chronic abdominal pain (Rock and Markham 1992).

3 Clinical Features

Endometriosis is almost exclusively found in women between 20 and 45 years old. Women who experience endometriosis beyond menopause presumably have chronic fibrosis or exacerbation induced by exogenous estrogens. Although most women with endometrial implants on intestinal structures are asymptomatic, those with serosal implantation may complain of abdominal pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, low backache, and localized tenderness.

Symptoms due to the penetration of endometrial tissue into the bowel wall may depend on the location of the ectopic tissue. If the rectum or the sigmoid colon are involved (posterior pelvic compartment), the main symptoms are dyschezia, tenesmus, and rectal bleeding, primarily during the menstrual cycle (52 % of cases), or partial obstruction with intermittent abdominal pain, constipation, and diarrhea (14 % of cases), respectively (Bianchi et al. 2007; Chapron et al. 2003). The invasion of the wall of the appendix or the ileum by the endometrial tissue may generate acute appendicitis, or strictures of the small bowel, with symptoms of acute intestinal obstruction due to fibrosis, volvulus, or intussusception, respectively. Symptoms are not always cyclical and may be independent from hormonal levels, and gastrointestinal manifestations are not necessarily associated with gynecological symptoms. For example, the hematochezia may occur when endometrial implants penetrate the mucosa of the bowel wall or when severe and chronic fibrosis results in ischemia (Bontis and Vavilis 1997).

4 Diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis may be difficult because symptoms and signs often are nonspecific and not always related to the menstrual cycle. Endometriosis should always be considered in women between 20 and 45 years old with gynecologic complaints and with recurrent abdominal pain or gastrointestinal symptoms.

An important component of the evaluation in suspected endometriosis is a careful examination of the pelvis that includes combined recto-vaginal palpation. The presence of a nodule or the irregularity in the recto-uterine pouch is highly suggestive of this disease. The pelvic examination should be performed before and after the menstrual phase because the lesion may vary during the menstrual cycle.

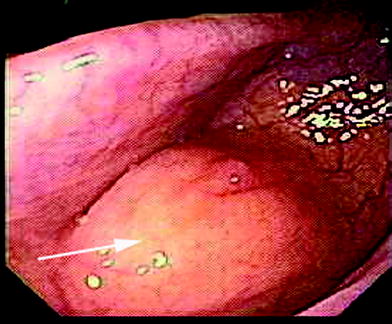

If the predominant symptom is hematochezia, colonoscopy is recommended. In patients without hematochezia, colonoscopy may be normal except for areas of extrinsic compression or strictures (Fig. 2) (Bozdech 1992). More helpful in these patients is the double-contrast barium enema, computed tomography (CT) colonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which can demonstrate submucosal polypoid masses or lesions narrowing the lumen.

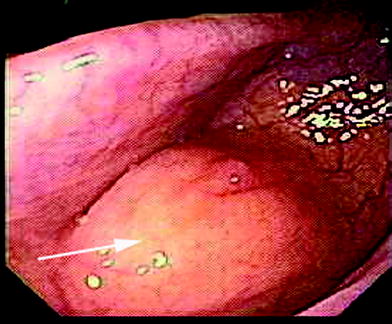

Fig. 2

Colonoscopy showing an area of extrinsic compression (arrow) due to intestinal endometriosis with normal appearing mucosa

Computed tomography scans, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging all have been reported to assist the diagnosis or the assessment of the extent of endometrial involvement. High-resolution transvaginal and transrectal ultrasound also may be useful in detecting endometrial implants, in particular in the retroperitoneal structures (Brosens et al. 2003).

However, definitive diagnosis of endometriosis is often made by laparoscopy or laparotomy with biopsy (Jansen and Russell 1986). The appreciation that endometrial tissue may be nonpigmented has increased the yield of these procedures considerably. Histology shows endometriotic foci characterized by variably sized glands lined by columnar epithelium embedded in endometrial stroma. Usually, fibrosis of the adjacent fat accompanies the process. Mucosal involvement can cause inflammation, polypoid lesions, ulcers, and fibrosis. The involvement of the submucosa often produces a smooth muscle reaction, featuring thick and irregularly arranged bundles of muscle. If the disease is extended to the muscularis propria it produces a disorganized hyperplasia of the adjacent smooth muscle (Kaufaman et al. 2011).

Recently, peripheral biomarkers, combined with non-invasive diagnostic procedures such as ultrasound or MRI, have been suggested as diagnostic aids in women with suspected intestinal endometriosis. However, despite Ca-125 and Ca19-9 are currently used in clinical practice, to date there are not a single biomarker or panel of biomarkers that have unequivocally been shown to be clinically useful in routine clinical care.

4.1 Ultrasonography

Ultrasound examination of the pelvis is the first diagnostic choice to identify endometriosis. The transabdominal ultrasound used to explore the pelvis, should be followed by transvaginal ultrasound (TVS) to obtain more details of the anatomical structures, such as the bladder, the ovaries, the uterus, the uterus-sacral ligaments, the recto-vaginal septum, and the recto-sigmoid (Piketty et al. 2009). Over the past decade, the use of TVS has improved the quality of non-invasive assessment of patients with suspected pelvic pathologies. Bazot et al. (2003) have suggested the potential value of TVS for the diagnosis of endometriosis and confirmed that the technique was able to accurately diagnose the endometriosis of the rectum, ovaries, uterosacral ligament, recto-vaginal space, pouch of Douglas, vagina, and urinary bladder. The sensitivities, specificities, and positive and negative likelihood ratios in six studies using gray-scale ultrasonography ranged between 64 and 89 %, 89 and 100 %, 7.6 and 29.8 %, and 0.1 and 0.4 %, respectively (Moore et al. 2002).

Improvement of the diagnostic accuracy may be obtained by performing TVS with saline solution in the vagina or with water-contrast enema in the rectum.

At sonography, both TVS and transabdominal sonography, endometriosis appears less frequently as cystic lesions with anechoic fluid content and hyperechoic blood deposits, or, more often, as hypoechoic thickening or nodules/masses with irregular contours, usually involving the deep layers of the bowel wall (Saba et al. 2012) (Fig. 3; Fig. 4).

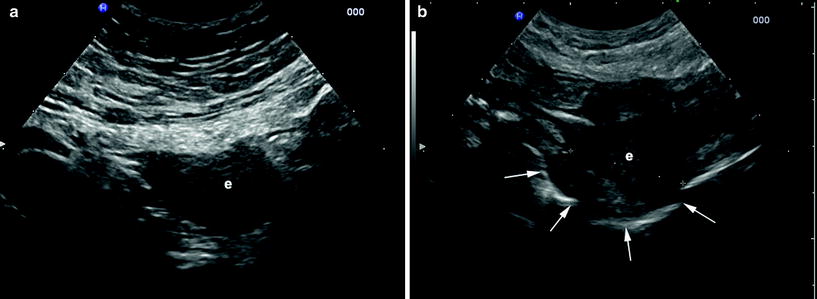

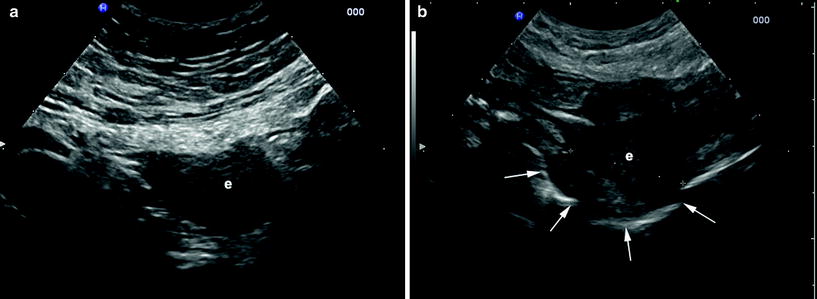

Fig. 3

Intestinal endometriosis detected by transabdominal ultrasound. a, b The lesions appear as hypoechoic nodules with irregular contours (e) involving the deep layers of the bowel wall. b The lesion deforms the intestinal lumen (arrows), easily detectable for its gaseous content

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree